That night, the howling of wild animals, wolves or jackals, was unbearable. “They are going to eat us,” a three-year old boy was crying as the sounds struck terror into his heart. His mother held him on her lap, hugged, and soothed him, “Dad will not let them eat us. Fear not, Mustafa.”

O n a cold night, in 1946, the Jemilevs were moving to a new home. They had the commandant’s permission.

“Those are my first childhood memories,” says Mustafa Jemilev, 75 years after the events. He is now a former dissident and political prisoner, sitting in a comfortable armchair in his study in Kyiv. The room is adorned with objects associated with Crimea, and on the wall hangs a painting depicting the view over Bakhchysarai.

“I was seven months old when we were deported. My family ended up in Uzbekistan, in the Andijan Oblast. Before our arrival, they had spread propaganda among the locals, claiming the traitors were coming. In many places along the road, the locals greeted the trains with a hail of stones. But they would calm down seeing women and children getting off the trains. We faced overt discrimination. We were under the commandant’s supervision; my parents were required to report to his office weekly. We were permitted to move within a four-kilometre radius from our residence. Visiting relatives for a funeral in a neighbouring village necessitated a special permit from the commandant. An unauthorised trip was treated as an escape attempt, punishable by 25 years in prison.”

Deportation of Crimean Tatars

False accusations of collaboration with the Nazis were used as a justification for the genocide of Crimean Tatars, committed in 1944 by the Soviet authorities.

Photo: Oleksandr Khomenko for Local History

Jemilev smokes a cigarette. Judging by the contents of the ashtray and the cloud of smoke in the room, it is not his first one.

The conversation is interrupted by the doorbell. A man and a woman enter the room, greeting Jemilev in Crimean Tatar. The woman gently touches Mustafa-aga’s hand to her forehead and kisses it – a traditional gesture, signifying respect towards the elderly.

Are you relatives?” I ask them.

“Almost,” the man smiles. “Mustafa-aga and I have played chess for hundreds of hours.”

Aga

A respectful address to men in Crimean Tatar.The guest retrieves a framed photo from a box. It shows Jemilev and him beside a chessboard. He hands the photo to Mustafa-aga for an autograph. Jemilev signs in Arabic script and in Crimean Tatar. While writing, he requests the man to download some cartoons onto his granddaughter’s tablet, “In Crimean Tatar, Ukrainian, Turkish, or English. Definitely not in Russian. She’s started speaking to me in Russian.”

The youngest of the Jemilevs is three years old. Mustafa-aga displays the latest photos of Meriem on his phone’s screen: a little girl holding Ukrainian and Crimean Tatar flags. ‘I ought to print this one as well and hang it somewhere here,’ he remarks, scanning the walls for the ideal spot for the photo. Meanwhile, Jemilev’s guest serves coffee for everyone and places sweets on the table.

“The greatest joy for Crimean Tatars in deportation was visiting each other,” says Mustafa-aga. “There was even a schedule: when they visited us, when we visited them. Even the poorest families would prepare some treats for guests, such as coffee. They were cautious about speaking openly in front of children. I remember my father beginning to talk about something, and my mother nudging him, whispering, ‘Hush, the children are here.’”

Jemilev’s door hardly closes. He has guests nonstop. Some are leaving, others are coming. They are joining us and listening to what Mustafa-aga has to tell.

Photo: Oleksandr Khomenko for Local History

‘The dog met his end’

“It was March 1953. Our radio was on. Levitan’s voice announced that Stalin died. And my father said, ‘Finally, the dog met his end.’ So, I went to school in that frame of mind. There, everyone was crying bitterly, as if it were the end of the world. Only the Crimean Tatars were not crying. Our leader, Reshat Bekmambetov, gathered us and said, ‘Look, everyone is crying except us. We must cry too, or our parents will be arrested.’ He even brought along some onion.

Yurii Levitan

Was the primary radio announcer in the Soviet Union.And then we had to line up in the schoolyard for the official announcement. A staff member of our school began a speech but couldn’t even finish because he burst into tears. I thought to myself: my dad had said that the dog had finally met his end, yet this man is crying as if his own father had died. Curious about what he would do next, I followed him. He entered an empty classroom, banged his head against the wall, and wept. It was such a psychosis.

Then they announced that, due to three days of mourning for the leader, there would be no classes. I almost shouted ‘hooray’ aloud! Had I actually done so, my parents would certainly have been sent to prison. I restrained myself and thought that this Stalin had done at least one good thing.”

After school, Mustafa Jemilev travelled to Tashkent to enrol in the Faculty of Arabic Language and Literature. However, an admissions officer confidentially informed him that he shouldn’t even try, as they had been instructed not to accept Crimean Tatars. Jemilev later understood the reason. Graduates in Arabic studies often went on to work abroad and became agents of the KGB, the Soviet security agency. And Crimean Tatars made bad agents.

Having failed to gain university admission, Jemilev took up a job at the aviation plant in Tashkent. He spent all his spare time in the library, voraciously reading every piece of literature about Crimea. He conducted research and made notes. Additionally, he practised Arabic script.

‘What shit Russia is’

“One day, while I was sitting in the department of rarities, two young men entered, conversing in Crimean Tatar. One approached me and remarked, ‘I see you’re reading in Arabic. Could you translate something for us?’ I did. He then asked, ‘Why do you only have books about Crimea?’ He asked this in Russian. I explained that I am Crimean Tatar. They were delighted. They told me they were engaging young people to create an organisation whose main goal was to bring Crimean Tatars home.”

They invited Jemilev to the organisation’s meeting to give a lecture on Crimea’s history. They met in a private house on the outskirts of Tashkent and discussed the statute, the oath, and their duties. They had arguments and rows. After an unknown young man delivered a lecture, the audience erupted into applause.

“I had never received such applause in my life. I spoke about things that would resonate with my audience, for example, how Crimean Tatars routed the Russian troops in 1711 near the Prut River, about how brave we are, and how Russians are shit. The lecture was handwritten. People took it, copied it, and passed it from hand to hand.”

A few weeks later, however, there were arrests. The police detained the owner of the house where the youths had been meeting, along with the leaders of the organisation, which hadn’t even been formally established yet.

“From that time on, all of us were under surveillance. Two were expelled from university. I was fired from the plant. Constant surveillance. I realised I was going to be arrested sooner or later. I started studying the criminal code, articles, comments, and court decisions. I read about the Nuremberg trials.

My task was to get moral satisfaction in court. Subsequently, I represented myself at all trials, and the judges were surprised at my extensive knowledge despite lacking a formal legal education. I sought to meet people who had been in prison to learn about the rules behind bars. Thus, I learned the main rule, later phrased by Solzhenitsyn as ‘Fear nothing, ask nothing.’”

At this moment, the young woman, Mustafa-aga’s guest, stands up from her chair and starts arranging his hair.

“What are you doing?” Jemilev looks surprised and confused.

“And his eyebrows, arrange his eyebrows too,” suggests the man, Jemilev’s chess partner. He also stands up from his chair to help the woman.

“What timing for this! What do you want? Women no longer pay attention to me anyway,” Mustafa-aga jokes.

slideshow

These spontaneous and somewhat humorous moments are underpinned by pure love and respect. Mustafa Jemilev is not just a national leader; he is also revered as a second father by the Crimean Tatars. And this respect is distinctly mutual.

When Jemilev’s guests are satisfied with his looks, we continue our conversation.

Hydraulic tests with the KGB

Mustafa-aga recounts how, after school, he enrolled at the Agriculture University in Tashkent in a technical specialisation that held no interest for him. Alongside his studies, he devoted himself to Crimean Tatar issues. He participated in rallies and met with his compatriots. He expanded his engaging lecture into a “Short Historical Outline of the Turkic Culture in Crimea in the 13th-18th Centuries”. The KGB called this work “a work with anti-Soviet ideas” and nationalistic positions. In his third year of studies, Jemilev was expelled from the university.

“After the assembly, I was approached by the head of the Department of Hydraulics Memet Seliametovych Seliametov. For him, I was nothing because I struggled with his subject, hydraulics. But he shook my hand and said, ‘Don’t think that I am one of them, I did not know they were going to discuss your expulsion today. I am not a Crimean Tatar myself, I am a Karaite, but I am appalled to the bottom of my heart that they justify the deportation of a whole people. What can I do for you?’ And I was going to have an exam in his subject. So I took out my exam card, and he gave me a ‘B’ right there, writing on his lap. I never had a ‘B’ in hydraulics. It was major moral support.

Karaites

Indigenous people of Crimea together with Crimean Tatars and Krymchaks.After that, I went to the rector’s office and saw a KGB officer there, who was dealing with Crimean Tatar issues. He said, ‘We will let you continue your studies if you write a penitential note and commit yourself to becoming a normal Soviet citizen and help the KGB fight with apostates.’ He was recruiting me to be their snitch. I immediately told the rector that I was leaving the university. And I congratulated the KGB officer on his victory over the counter-revolution. As I was leaving, he called me ‘scum’ or ‘scumbag’ or something.”

Source: Local History

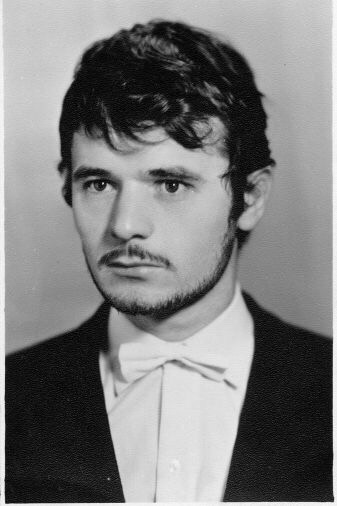

First arrest of Mustafa Jemilev

Next day, Jemilev received summons to the army. He refused to serve. His reasoning was, “I refuse to serve in the Soviet army because I have no motherland to defend. Moreover, I do not believe that I have enemies outside of the Soviet Union.” This led to his first criminal case and arrest.

“They sentenced me to a year and a half. I was sent to the Kulyuk camp for the criminals on the outskirts of Tashkent. They took away my shoelaces so I wouldn’t hang myself. I also had a bow tie, instead of a necktie. Those were trendy at the time. They took it away too. So, I was walking back and forth in the camera, anxious. And one intimidating criminal said to me, ‘Why are you running around, sit down, I can’t relax because of you.’ I knew that had I sat, it would have meant I was scared. And that would have been the end of my life. Where did I get the courage from? I stuck two fingers out as if I was going to stick them in his eyes, went closer and said, ‘Were you talking to me, jerk? You will relax at home. This is not a hotel for you.’ He was looking at me like I was crazy, and I was thinking: if he stands up, I will be smashed on the wall. But he was like, ‘Are you losing it? I only told you I could not relax because of you.’ And I repeated, ‘You will relax at home!’ In prison, there is a law: you cannot show weakness.”

A month before his release, Jemilev and another Crimean Tatar prisoner were taken to isolation cells. They were commanded to sign a commitment of surrendering their anti-Soviet efforts. Mustafa-aga went on a hunger strike. Ten days later, he was released from the isolation cell without signing. He left the prison with the following reference: “negatively characterised, developed relations with influential criminals, fluent in English and Arabic, and requires constant surveillance.”

At the earliest opportunity, Mustafa Jemilev headed to Moscow, where he became friends with famous Soviet dissidents: Petro Hryhorenko, Petro Yakir, Pavel Litvinov, and Viktor Krasin. General Hryhorenko became an advocate for Crimean Tatars, his apartment serving as the headquarters for the anti-Soviet powers. Jemilev lived there for six months. He called Petro Hryhorenko’s wife “my Russian mother.”

Petro Hryhorenko

A Ukrainian human rights activist and Soviet dissident. A founding member of the Moscow and Ukrainian Helsinki Groups. He spoke in defence of the Crimean Tatars and other deported peoples.Only half a year passed between the release from prison and another arrest. Jemilev was tailed all the time. For some time, he had managed to steer clear.

“Around 1968, following the occupation of Czechoslovakia, mass arrests of dissidents began. I was staying at my sister’s house. In the evening, I prepared all my documents to destroy them the next morning. Peering through the window, I spotted a detective. Clad only in a vest, trousers, and socks, I jumped out of the window with all the materials. I concealed myself in the vegetable garden, hidden among the tall maize. I returned at night to find my sister in tears – they had taken her husband. They had left a summons for my interrogation. My brother-in-law was sentenced to three years. Later, my sister would later make fun of him, ‘Actually, they came for Mustafa, but since he wasn’t there, they took you just to avoid leaving empty-handed.’”

Second arrest

Mustafa Jemilev enjoyed only a brief period of freedom before being arrested again in September 1969, this time for “deliberately disseminating false information undermining the Soviet state and social order”.

Jemilev says this was the same reason given for imprisoning a Soviet dissident, poet Ilya Gabay. They were both detained at the Lefortovo isolation ward.

“Already after I had been released, I came to visit my brother-in-law. We were working in the garden and listening to the Voice of America. We had a Spinola record player at the time. And I heard the report, ‘Today, a famous dissident Ilya Gabay threw himself out of the window of his apartment on the 12th floor.’ I did not believe it. I had talked to him on the phone a week before that. I went to call his wife. She confirmed he had done it himself, he had left a note. He was depressed because both Petro Yakir and Krasin had testified against him. And he had a hard time in prison. He was an intellectual among criminal scum, swearing, cruelty. He could not handle that.”

Ilya Gabay

A Soviet Jewish writer, teacher and dissident born in Baku, Azerbaijan. He was fighting for civil rights, and became involved in the struggle for the Crimean Tatar autonomy. He was persecuted by the Soviet authorities, fired and imprisoned several times. He committed suicide on 20 October, 1973.Third arrest, fourth case

Two years later, Mustafa Jemilev got provoked into a fight, and was put into prison for 15 days for “hooliganism”. The Crimean Tatar dissident went on a hunger strike, got a complication of a stomach ulcer and refused to go on a half-year military training. He got a year in prison for that.

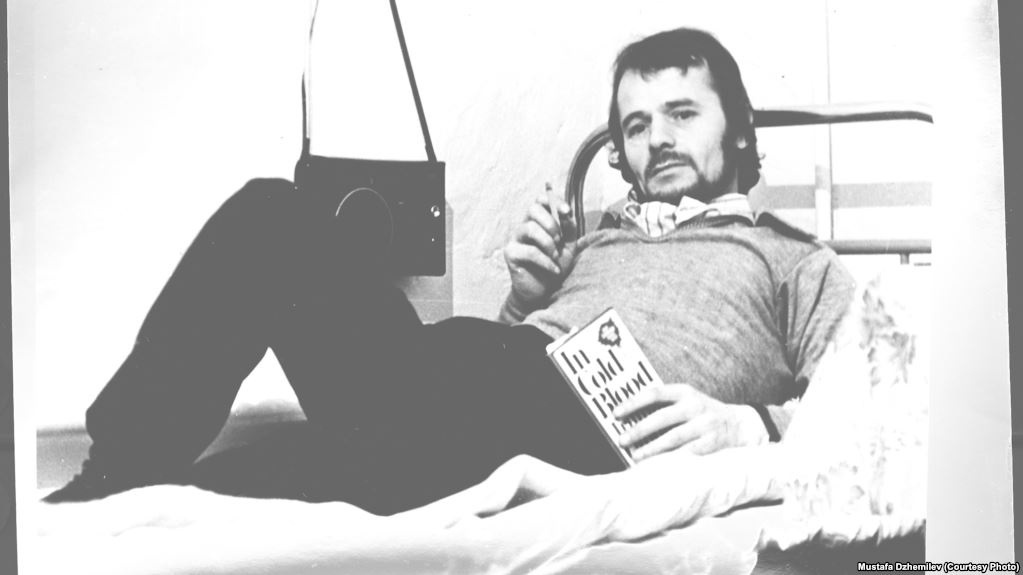

Source: Local History

In the penal colony in Omsk, just before his scheduled release, Jemilev realised that they had no intention of letting him go and were concocting a new case against him. The detectives interrogated his cellmates and managed to find a prisoner who testified against him. His written works were confiscated.

“They seized the ‘Declaration of the principles for national movement of the Crimean Tatar people’. I wrote it in Arabic script. The language was a mix of English, Crimean Tatar, Russian, with maximal abbreviations. They decoded it. They invited the head of the English language and literature department of the Omsk university. A teacher from Tashkent translated the Arabic part. They recovered 90% of the text. I knew they would add new accusations and try me without letting me out of prison. Then I went on a hunger strike. I wrote a letter to academician Andrei Sakharov. It was delivered. And Sakharov started a campaign about my hunger strike.”

Andrei Sakharov

A Soviet physicist and a Nobel Peace Prize laureate (1975) for emphasising human rights around the world. From 1980 to 1986 was imprisoned together with his wife, Yelena Bonner.In 1975-1976, the case of Mustafa Jemilev was widely covered in the western media. Thanks to his lengthy hunger strike, the world learned about a whole nation (Crimean Tatars – ed.) driven from their homeland.

On the seventh month of his hunger strike, British newspaper The Times announced that Jemilev may have died in the Omsk prison.

“It turned out like this: my mother came to Omsk to see me. And the camp commander told her: your son is not here, go away. And she went to Moscow to see Sakharov in tears. Sakharov and Hryhorenko held a press conference and announced that it was possible that Jemilev had died. The information went around the world. In Turkey, I was buried in mosques, poems were composed, and Soviet consulates were smashed.”

After many years, Jemilev is telling that story with a smile on his face. As if there was nothing exceptional in those 303 hungry days. His voice does not break even when he speaks about forcible feeding.

“If the smell of a dead body is felt from the mouth, that’s a sign of lethal outcome. The wardens hold you by the arms and open your jaws with a tool – usually, they would break your teeth this way – they stick a hose in your mouth and pour in nutritional liquid. It keeps you alive. It is quickly absorbed, and after an hour you feel hungry again.

On the seventh-eighth month of the hunger strike, a therapist and a psychiatrist came to visit me. The therapist examined me, checked my blood pressure. The psychiatrist started asking questions. And I said to him, ‘Why are you here? I did not proclaim myself Napoleon, I do not bite anybody.’ And he said that after long-term hunger, a person can have mental disorders, and his duty is to check my condition. When we were alone, he said to me, ‘In fact, they brought me to convince you to stop your hunger strike, but my advice is push them till the end. It’s a huge blow for them. All the media are writing about you. Hold on.’ And he left.”

The trial took place on 14 April 1976 in Omsk. Jemilev was brought in a stretcher. He could not walk by himself.

From left to right: Yelena Bonner, Safinar Jemilev, Mustafa Jemilev, Andrei Sakharov. Mustafa Jemilev's archive

Andrei Sakharov personally came to the trial. The Nobel prize laureate was not allowed inside. In the clash, a militia officer pushed Sakharov and received a slap from Sakharov’s wife Yelena Bonner. The couple were pushed in a car and taken out of the city. In the meantime, the judge announced Jemilev’s sentence – two and a half years in a strict regime corrective colony.

“After the trial, I had a meeting with my mother and brother behind the glass wall. My mother burst out crying, she didn’t feel well. And my brother said, ‘I know there’s no point in trying to convince you.’ But he held a card to the glass from Sakharov. His message was very touching: ‘Son, I did all I could to take you out and to make your story known around the world. Your death will only make our enemies rejoice. So now I am asking you to stop your hunger strike.’”

As we are talking, Jemilev keeps telling jokes. But this memory brings tears to his eyes. Sakharov’s words made him stop his hunger strike: he wrote the statement right at the meeting with his family.

After that, Mustafa was taken to the hospital. Two months later, he was already on his way to the Russian Far East to the Primorski strict regime camp.

“We arrived, a total of around 30 prisoners. And the procedure was that you are kept in the special department until they send you into the ‘zone’. Each prisoner is called for a conversation to determine where they would be assigned to. Everybody left but I wasn’t called. They said the commandant wanted to talk to me personally. He was supposed to be there in two days. As two days passed, they called me in. I entered the room, told my last name, first name, what I was accused of, and my prison sentence. He just looked at me, ‘Are you Jemilev? Mustafa?’ I said, ‘I am’. And he started laughing out loud. I stood there wondering. And he explained, ‘Don’t get me wrong, people told me a lot about you, I thought a big brutal man would come in and will cause trouble, and this is what you look like.’”

After the exhausting hunger strike, Jemilev was not capable of doing physical work, so he was sent to work in a laboratory. He quickly made new acquaintances because he could find a common language with everybody.

“If the administration did not provoke conflicts on purpose, the criminals were tolerable. They had vested interest in political prisoners because they were knowledgeable. They called me ‘politician’. They came to me for consultations. And in the camp in Omsk, I had the nickname ‘prosecutor’. They brought me their cases, I read them and if I found anything odd, I told them ‘serve your sentence, they did right, those that put you in prison.’ But if I found something interesting, I helped them to write enquiries and complaints to have their cases reviewed.”

After Jemilev’s return from the camp, he was under constant surveillance, with every move closely monitored. He never ‘corrected himself’ as the Soviet law enforcement system expected. He continued to associate with those deemed untrustworthy and signed letters supporting dissidents. Mustafa-aga petitioned the Supreme Council of the USSR, requesting to be stripped of his citizenship and allowed to leave the Soviet Union. He added a condition, stating that he would reconsider if the Crimean Tatars were permitted to return home.

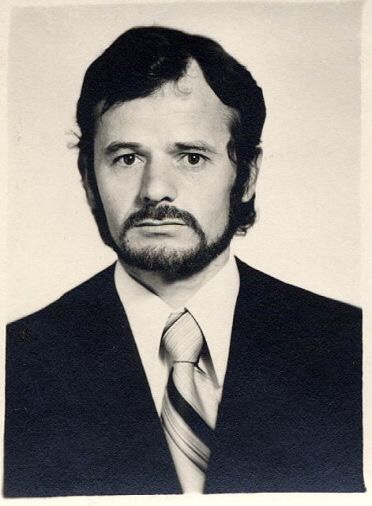

Mustafa Jemilev in 1979. From the personal archive

Fifth arrest and wedding

In 1979, Jemilev was sentenced to imprisonment for a year and a half. This sentence was replaced with a four-year exile to Yakutia.

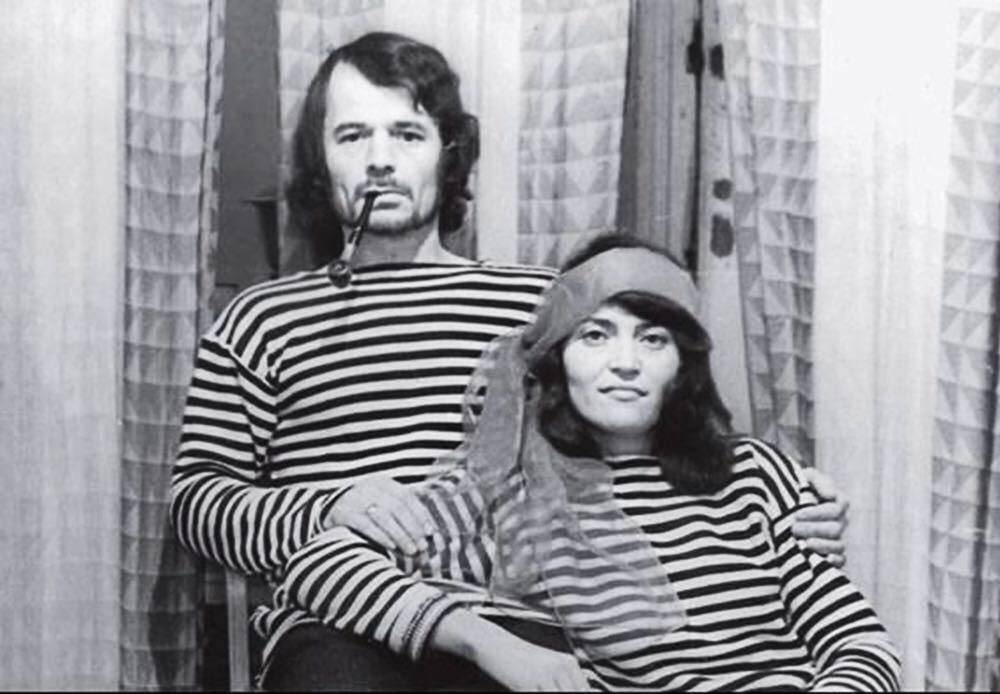

“Our friends sent a strong young man to live nearby and protect me. He told me about a patriotic woman, a beauty. Her husband died of cancer, and she stayed with her son. She was such a patriot that she wanted to sell her house, move in with her parents, and donate the money to the Crimean Tatar national movement. That impressed me. I asked for her address, and we became penpals.

Later, there were many jokes about why she married me. I said: she heard on the radio that I did not eat for 303 days and she thought she wouldn’t need to feed me.”

Mustafa Jemilev with his wife.

Mustafa Jemilev bursts out laughing and lights up another cigarette, it is his eleventh during this conversation. With that lighthearted intonation, he continues telling his love story, how he fell in love with the letters and a beautiful woman from a photograph.

“She visited me in summer. We went to the registrar to get married. She put her signature. I was waiting. The employee asked, ‘Why are you not signing?’ I looked at Safinar and asked, ‘Are you going to insult me?’ She said, ‘No, no.’ And only after that I signed. There, in exile, she got pregnant, and we came back already with our son Kheisar.”

Three days in Crimea. The sixth arrest

In February 1983, the exile term was over. Jemilev left Yakutia to go directly to Crimea where he was born, which he did not remember at all, and which he was dreaming about for 39 years of his life as the promised land.

The Jemilevs stayed on the peninsula for three days only. They were put in the police car and taken out of Crimea. Then, the family went back to the city Yangiyol in Uzbekistan. There, Mustafa Jemilev became the editor of an illegal information bulletin of the Initiative group of Crimean Tatars named after Musa Mamut. Soon he would be under repression again.

Jemilev was arrested in November 1983, six months after his return from exile. He faced charges of composing and disseminating documents that slandered the Soviet order and its political system, recording broadcasts from enemy countries, and orchestrating riots. He received a three-year prison sentence.

He was dispatched to a high-security corrective colony in the Magadan Oblast, once again among criminals. Mustafa Jemilev concludes that he was never held in camps specifically for political prisoners.

Mustafa Jemilev at the entrance to the village Ai-Serez in Crimea, 2005.

Seventh arrest and Reagan

In 1986, another case was opened against Mustafa Jemilev, the last one in the Soviet Union.

Jemilev was sentenced to three years’ probation and was released right from the courtroom. He was not put behind bars thanks to the pressure of Reagan on Gorbachev. The USA stood up for the political prisoners of the Kremlin.

The great and powerful Soviet Union was already bursting at the seams. Jemilev made his contribution too, measured with 15 years in prison or in exile.

“Tashkent, Khavast, Moscow – ‘Lefortovo,’ Omsk, Novosibirsk, Irkutsk, Vladivostok, camp ‘Primorski,’ camp in Omsk, Petropavlovsk,” Mustafa-aga names the places where he served his sentences.

With his peculiar humour, he adds, “They showed me the whole country, but through the window of a police car.”

Eighth Arrest. Russia

Today, Jemilev is being tried again. In absentia. He is accused of three articles of Russia’s criminal code. Russian occupants in his native Crimea are staging a play: they open a trial, interrogate witnesses, and pretend to be leading a legal process. Jemilev’s home has been closed to him since 2014.

“The Soviet authorities were afraid of the world community. They spent billions on propaganda. They did not want negative information to spread beyond the borders of the USSR. And Putin doesn’t care. He is way down on the bottom. He is all about intimidating and keeping power.”

Photo: Oleksandr Khomenko for Local History

“Today, they are more active in physically beating out testimonies. With no sanctions, they surround the house, break in, put everybody on the floor, and search. All this just because they heard something in the mosque. In Russian prisons, today there are 77 Crimean Tatars, most of them accused of terrorism,” says Jemilev.

In the corridor of his apartment-office in Kyiv, there is a big map of Crimea. With old Crimean Tatar names of locations, which had been in use until the October revolution in 1917. The map is not here as a reminder of who Crimea belongs to. It is a guarantee that Mustafa Jemilev will come back to the peninsula like he did in 1989, because Crimea is his motherland and his home.