Reshetylivka, a town in Poltavshchyna, is a true treasure of Ukrainian folk art. Masters of weaving, carpet manufacturing and embroidery from Reshetylivka have been famous across Ukraine since the end of the nineteenth century. High-quality wool from a local breed of sheep, unique hand embroidery and weaving techniques, and national heritage lead to a rapid growth of folk art in Reshetylivka.

But nowadays, with more advanced means of production and commercialization, the role of traditions — in particular, carpet manufacturing — is diminishing. High quality weaved carpets are expensive, and so they are not in demand. The same is true for tiles made in Kosiv and a whole range of unique folk art traditions. When there is no demand for tradition, it is threatened with extinction. The artists who have been preserving traditions are few and far between. The Piliuhins family not only continue the tradition of carpet weaving but also develop it and pass their knowledge to younger generations.

For centuries, Reshetylivka has been in the thick of historic developments. Throughout the years, the town had been governed by either Polish or Russian authorities and Ukrainian cossacks. In the times of the Khmelnytskyi Regiment in the seventeenth century, Reshetylivka was a sotnia town (unit of the Cossacks regiment).

For many years, Reshetylivka has offered ample opportunities for the development of industry and trade and has been used as a venue for large-scale fairs. At these fairs, craftspeople would sell fabrics, vyshyvankas (embroidered shirts) and carpets.

Carpet weaving, as an artistic craft, gained popularity during Kyivan Rus times. Now it is a pretty rare craft that is evolving only in the historic centers of carpet weaving in Ukraine, including Reshetylivka.

For a long time, folk art was just a pastime until in 1905 when a weaving workshop was established in Reshetylivka and was soon turned into an artel, a worker co-operative. With the purpose of providing professional training for aspiring craftsmen, an art training school was opened in Reshetylivka in 1937 and still exists today.

In 1960, the artel was mechanized and became the Reshetylivka factory, named after Clara Zetkin. Workers produced tapestries, carpets with floral or geometric patterns, blankets, scatter rugs, and plenty of other things on request.

Reshetylivka was a hot spot for artists from all across the USSR. Not only was it a place which allowed adopting best practices of local craftspeople and derive inspiration from the breathtaking landscapes of Poltavshchyna, but it also allowed them to stay for a while, as Reshetylivka art training school provided ample job opportunities.

slideshow

This is how Yevhen and Larysa Piliuhin found themselves in Reshetylivka. The gifted couple was invited to teach in the training school as two professionals with the expertise in the field of folk art. Larysa shared memories about offering to take up a part-time job at the factory and being rejected by the director of the enterprise:

— He said, “Everything is dying.” — “What do you mean ‘dying’? We must revive things!” And he said, “Do you know how much time it will take to resume our work? About fifty years.” This is how it decayed, leaving only brick walls behind. Everything made of wood was stolen piece by piece. We begged them to give machine tools to craftspeople, or at least sell it. But we got no response and the tools were simply burned down. This is how the art died.

The famous factory was shut down in 2005. Together with some weavers, entrepreneur Serhii Kolinchenko founded “Solomiia” — a workshop of artistic crafts in Reshetylivka. In the shop, there are eleven employees who create various artworks, not only for Ukrainian customers but also for export.

The workshop is comprised of separate departments of manual and automated embroidery and weaving. Recently, there has appeared a computerized embroidery department — now the machines produce a pattern on the fabric according to a template.

Employees joke that there are two categories of carpet manufacturers: “authors” and “executors” — artists who draw up sketches and carpet makers who weave the carpets. They produce mostly tapestries and souvenirs, depending on what is in demand.

Currently, the workshop personnel are working on a project called “Maintaining Traditions — Creating Future”, with the ultimate goal of founding a Training Center of Art Industries where young people will be taught the secrets of carpet manufacturing and where the works of craftspeople of Poltavshchyna would be exhibited. With time, the center will be turned into a mini-museum and a tourist attraction of Reshetylivka. For this purpose, Serhii Kolincheko, the owner of the workshop, is raising donation funds:

— If we manage to carry out this project, it will save the unique folk art from imminent extinction.

Nowadays, there are few carpet manufacturers left in Ukraine. One of the reasons for such scarcity is a lack of demand for carpets and no efficient way of perpetuating the tradition. The second pressing problem is a low quality of Ukrainian raw material, said Olha Piliuhina, the younger daughter of Larysa and Yevhen:

— Wool is delivered from New Zealand. Sure, it is of high quality but also extremely expensive. Ukrainian wool tends to be crude, thorny, and sometimes contains burrs.

Reshetylivka used to have its own breed of fine-fleece sheep, which was known across Ukraine. Unfortunately, people did not manage to preserve this breed, and it no longer exists.

Back in the day when there was plenty of high-quality wool, carpet manufacturing in Reshetylivka was rapidly developing. As Olha told us, it was not hard to make a wooden workbench — that’s why there was one at almost every household. This allowed people to weave at home, sometimes copying the templates of factory-made carpets they saw in newspapers.

Every now and then, craftswomen would reproduce the factory-made carpets at home.

Now Reshetylivka boasts several centers of carpet manufacture, with the following as the most renowned of them: the workshop of art industry “Solomiia”, the Resetylivka art training school, and the home workshop of the Piliuhin family.

Piliuhins

The Piliuhins have been living in Reshetylivka for over 45 years now. Larysa, Yevhen, and their little daughter Natalia moved to Poltavshchyna after they graduated from the Moscow Art and Industry Training School named after Kalinin.

Larysa studied at the Faculty of Artistic Embroidery and Lace Manufacturing. She inherited the fondness of embroidery from her mother. She recollects that there was a trend for embroidering “on canvas” and “cross” style. There were no other techniques. That was the sole reason why Larysa made a decision to take up embroidery as a profession.

It was the same year Yevhen enrolled in the training school. He wanted to major in carpet manufacturing. At first, they did not want to accept a Ukrainian student, as they were training specialists for Central Asia. Instead, Yevhen was offered a place in the embroidery department.

— Having received an acceptance letter, Yevhen kept it away from his parents, because it was addressed to “Yevheniia”, — Olha said with a smile. — So when he arrived on campus, everything was fine, but as soon as the practical sessions started, the craftsman who was teaching a class was surprised to see a guy among the girls. “How is it possible?”, he asked. “You aren’t a girl, are you?!” So they instantly changed his major to carpet manufacturing.

Now Yevhen is an artist, an Honored Master of Ukrainian Folk Art in Carpet Making. Larysa, Natalia, and Olha are members of the National Ukrainian Artist Association and Folk Art Masters Association.

Larysa said there are fourteen artists in the Piliuhin family.

Before moving, Larysa had no connection to Poltavshchyna. She was born in Russia. Yevhen, originally from Zaporizhzhia oblast, was more familiar with the local territory, as he had been doing his graduation work in Reshetylivka.

In Poltavshchyna, Larysa got interested in Ukrainian ornamental patterns and national symbols. The woman has embraced the knowledge passed to her by local craftswomen and has applied new skills into her art work.

This is what Larysa Piliuhin tells about the self-identity:

— People ask me, “Have you forgotten your origin?” Well, how could I possibly do that? What about my kids who were born here? What is their nationality — Russian or Ukrainian? I guess they are Ukrainian. Considering that I had been living in Russia for 19 years, and starting from 1973 I’ve been living here — who am I then? Obviously, I am a Ukrainian to a greater extent than Russian.

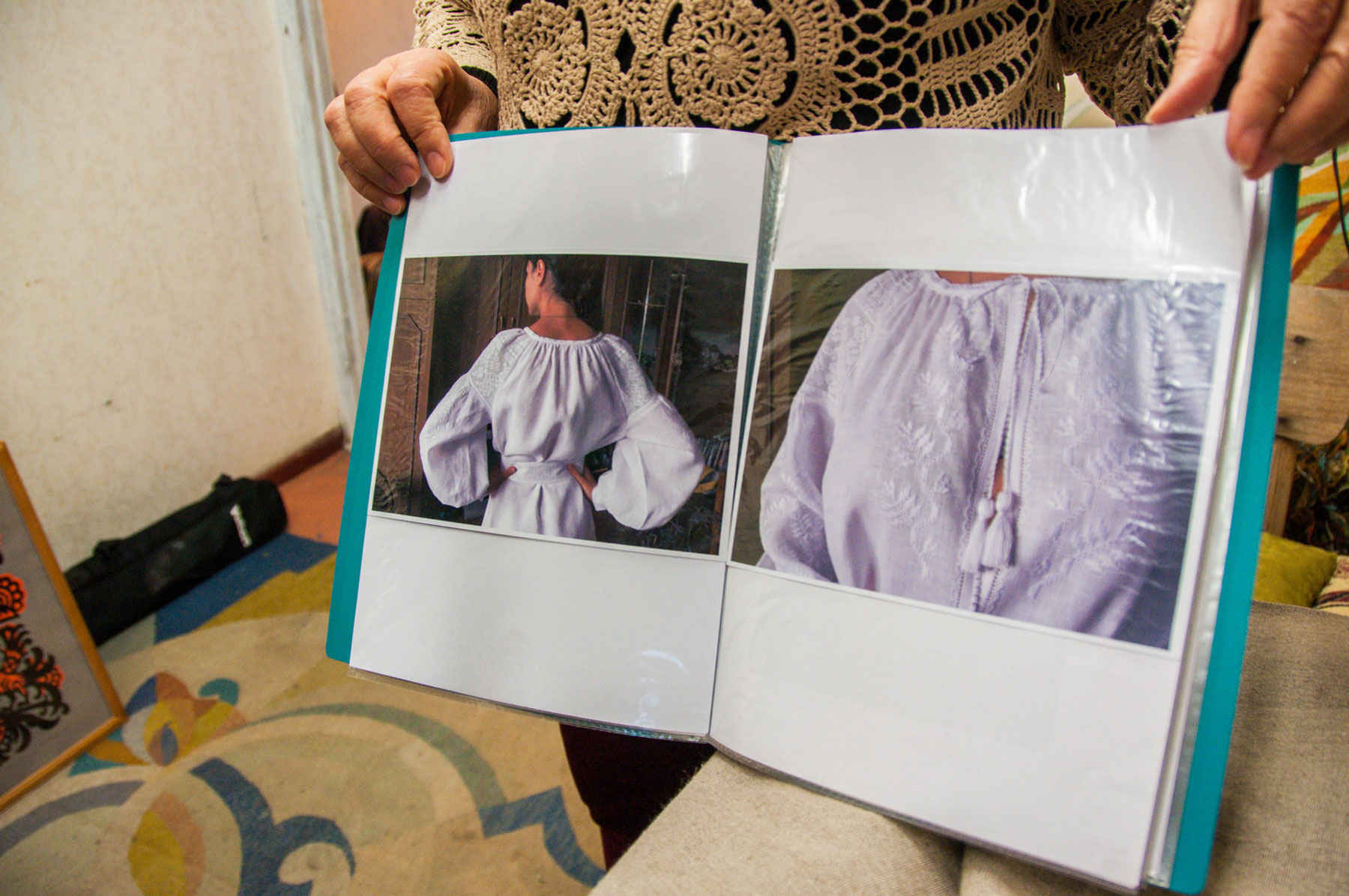

In Poltavshchyna, the woman got acquainted with a number of masters of Ukrainian embroidery and adopted their knowledge and skills. Larysa acknowledged being impressed the most with “white on white” embroidery. This very technique, as she said, is a genuine cultural heritage of Poltavshchyna:

— For me, it was easier to master the Ukrainian technique in particular, because they can be somewhat similar, somewhat different, and absolutely outstanding. I wasn’t embarrassed to ask questions about what to do and how to do it. I would sit down and do it on my own, because what choice did I have? Having dived into the Ukrainian national ornamental patterns, I started making Ukrainian works instead of Russian.

Nataliia, the eldest daughter of Larysa and Yevhen, makes carpets and traditional Ukrainian dolls called “motanka” (a doll made of cloth). Natallia is also a scholar of the Poltava Art Museum and an Art Gallery named after Mykola Yaroshenko.

Olha, the youngest daughter in the Piliuhin family, was born in Poltavshchyna. From early childhood, she has been fond of handicraft. She spent a lot of time in the carpet making factory playing, weaving, and embroidering.

When Olha turned 12 years old, Nataliia said to her, “Enough with playing. Let’s get serious about it.” The older sister showed Olha how to hold her hands in the right way and taught her some techniques. Soon afterwards the girls started working on large carpets together. Olha shared her recollections of that time:

— We would sit near each other. So I practised. At first, I cried, because Natalia would always finish her work and leave, and I had to catch up in order to reach the specified line, because I knew there would be more work the next day. I had it all — my back hurt and my fingers were worked to the bone, but I never asked what it all was for.

By the age of 14, Olha could weave professionally. When it was the time to choose a major, the girl opted for learning something new and enrolled in the Reshetylivka art training school with a major in hand embroidery. Later, she studied ceramics in Poltava National Technical University named after Y. Kondratiuk. Now the woman is professionally occupied with carpet manufacturing and also other types of traditional art.

The Piliuhin family makes a living through their art.

Art is the primary business of the Piliuhins family. There was a time when Yevhen helped his daughters to make sketches for carpets, but now it is a renowned family workshop where each artist has his or her own identity:

— As I child, I took it close to the heart when my father completed my work, — Olha said with a laugh. — I used to leave my unfinished works in the workshop and walk away. The next day I would come and see my father putting finishing touches to my work. Now we both give pieces of advice to each other. Every artist faces a block once in a while. That is why working together is a good thing — you always have someone to consult with.

slideshow

Olha insists that one should make art only when one feels an urge to do so. To this end, each piece of work takes a long time, as the artists of Piliuhin family care about the creative nature of the work:

— If your work is driven only by thoughts about money, it will be no good. You should forget about the money and care only about the art. Well, if art is a source of income, it is a nice bonus.

The origin of the carpet

Handmade carpets are not just an interior design elements. Each piece is a unique and one-of-a-kind example of folk art and master’s individual style. The Piliuhins consider carpet making an art, above other things. Olha claims that the creation of each carpet requires a lot of time, effort, and love:

— A factory standard is ten centimeters of the weaved cloth per day. But they just strive to get more footage of the weaved cloth forgetting about the creative part. On the other hand, if you take a close look at my work, you can distinguish every inch — the piece may contain over a hundred shades.

The process of creating a carpet is quite interesting. As Olha said, as soon as the idea pops up in your mind, you must put it in a sketch. Afterwards, the composition is painted as a full-scale draft, which is exactly how the carpet will look. The draft then is put behind the yarn base so that the author could see what he or she must reproduce with the yarn and which shade to select for a particular part of the work.

Olha mentioned that sometimes she gets ideas for her work spontaneously. These are the works which depend on the mood — that’s why they must be instantly put into action, otherwise you can lose inspiration. Olha can work on several pieces at the same time, as each of them requires their own mood.

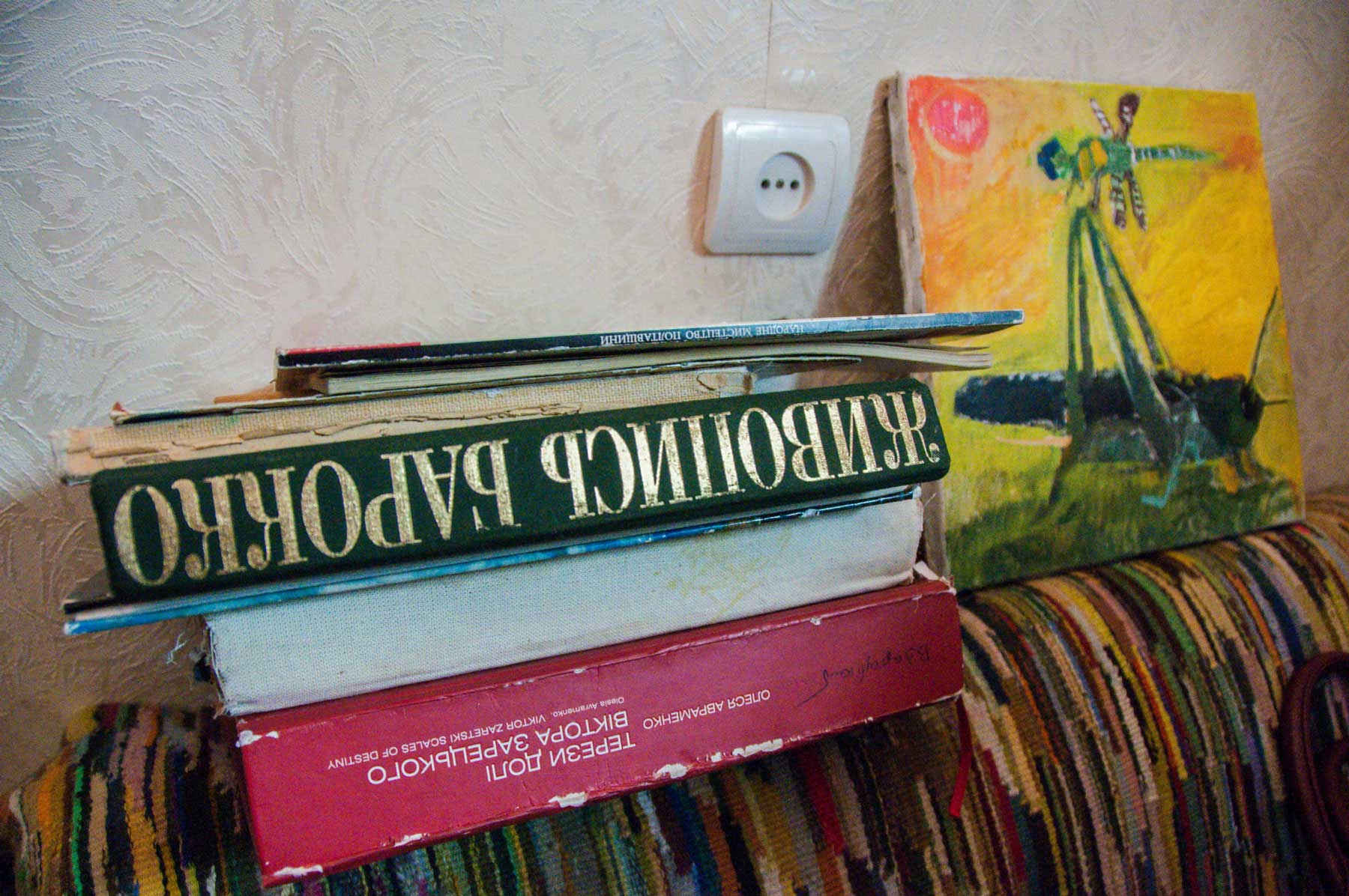

Theme-based works require more time to be implemented. Olha has a few pieces with the ornamental patterns of Trypillia. She drew inspiration for this topic while studying the Trypillian ceramics. She was also interested in the period of the Kyivan Rus: she researched its architecture, jewelry, paintings, frescoes, and so on. The woman said that once you figure out the specific nature and authenticity of a particular period, the next piece of work does not cause any troubles:

— But these are the original works. They are not the compilations of, let’s say, various details and patterns. I mean, this is not a collage. Now I am working on the carpets in the Cossacks baroque style. I am trying to reproduce those vibes, but nothing like that has ever been done before.

Olha picked up the topic of Cossack baroque with the “Hetmanskyi” carpet, which she made in 2014 as an entry in pursuit of a presidential grant. The period of Cossack baroque is known for a growth in carpet weaving, since back then the Cossack authorities supported carpet workshops and contributed to their development. Back in those days, a large variety of carpets with ornamental patterns were made. Most of them were made on a black or gold background:

— I created a bright, accomplished, expensive carpet with ornamental pattern. I wanted it to embody all the luxury and flourishment of those times. I was so satisfied with the result of the “Hetmanskyi” carpet that I decided to keep working on this topic. “Kozatskyi” carpet is the third piece of this series.

As Olha told us, working with ornamental patterns requires more time and concentration. Each detail of such work is elaborated, and each object (a flower, a bird, a leaf) is flat, does not overlap with other elements, and requires its own space. All elements must interact seamlessly:

— It is like some kind of an engine, like an organism where each part must be compatible with others in order to work. Lately, I have been doing more works with ornamental patterns, because I think that it connects us to our ancestors. When I work on such pieces, it overwhelms me with joy.

Once per year, Olha’s legacy is enriched with a new ornamental canvas. The artist creates the compositions with ornament pattern on her own with reference to national traditions.

Weaving looms used by the Piliuhins are not ancient but designed according to an old-fashioned principle, comprised of two pillars, two beams, two rolls, and a frame. This whole machine looks like a huge frame with yarn strung on it:

— People call such weaving loom “krosna”. This loom type used to be popular mostly in central Ukraine. “Krosna” makes it possible to weave using the most sophisticated techniques, use various types of material, and create superb products.

Manual carpet manufacturing is based on interweaving the longitudinal and lateral yarn. During this process, each hand is doing its own thing: the right hand is picking the back yarn and the left hand deals with the front yarn. The most complex and widespread technique in Ukraine (especially, in Poltavshchyna) is “circling”, which means that colorful yarn is loosely interspersed with yarn on a frame, creating smooth lines.

To condense the wool, you need a comb. Olha insists that it may also be done manually, but a wooden comb makes it easier, since when there are yarn tips, you can cut them and they won’t get loose under their weight, as they are condensed.

Yevhen dyes the yarn. The Piliuhins purchase natural sheep wool of pristine white color. The yarn is then dyed with permanent wool color.

It is not an easy task to calculate how much yarn is needed. As Olha explained, a lot depends on the sketch itself and the number of shades.

Carpet manufacturing has never been a cheap craft, as it has always required expensive material and long-lasting arduous work. As of now, nothing has changed. The cost of producing such carpet is quite high.

— People have no clue what it takes to make such a thing. As a rule, when it comes to traditional art, people believe it must be cheap and simple. No one considers how much time, efforts, patience, experience, and proficiency it requires, not to mention the materials and years of training you need to have to make such a piece of art.

Carpet manufacture school

An art lyceum in Reshetylivka is more than 80 years old. Until 2016 this educational establishment was called a training school, however, the title was changed after the law on decommunization had been adopted.

It takes two years to obtain a qualification for making embroidery, carpets, weaving, and painting in the lyceum.

Students from various oblasts (administrative units) of Ukraine study the peculiarities of folk art of all country regions. Instructors teach theory, craft basics, and provide samples of how to perform an art work.

Carpet making at the lyceum is taught by Petro Shevchuk, the former senior artist of a factory in Reshetylivka. Petro teaches weaving techniques to his students and explains the peculiarities of carpet weaving traditions typical of the Poltavshchyna region:

— The colors of Poltavshchyna lack contrast. Pastel and natural shades are more common. They are soft and calm, resembling a melody. This is a historical peculiarity of traditional handiwork typical of Poltavshchyna, which modern craftspeople are trying to preserve.

etro admits being concerned about the future of his students, as carpet manufacturing requires a lot of money, and it is common for artists to experience a lack of resources needed to implement their sketches on a canvas. After the factory in Reshetylivka had been shut down, aspiring artists struggled to find a job with their qualifications, as there are few enterprises in Ukraine that deal with carpet manufacturing. Even in a workshop in Reshetylivka, lyceum graduates are not allowed to start working immediately. The head of workshop claims that there is a reason for that, as it takes time for students to sharpen their skills.

— We do not have enough money for every piece. It used to be easier at the factory, where you would make a sketch and turn it into a carpet right away, — Petro said. — You were not supposed to invest your own money. The piece would belong to the factory, but still it was you who made it, who let the world see it. Now, to release something you would need your own money, but you don’t always have enough of it.

Besides, as Petro mentioned, most modern enterprises tend to break tradition and focus mostly on mass trade, on the things which can be easily sold. In this case, carpet making is no longer an art calling but a mere mundane task.

Olha said that now children are taught the craft in the lyceum, but the artistic nature of this occupation is neglected.

Whether they will make a work of art or kitsch depends on an artist’s inner world, the way he or she has been brought up and his or her priorities, explained Olha. That is why two artists can never make the same piece, even if they use the same colors and yarn. Enterprises constantly strive to increase their performance by means of mechanization, but the reduction in variety makes their products rather simplified and depletes local coloring. Production of such pieces is defined solely by what is in demand.

Olha teaches painting and weaving to the primary school students. For now, there are twelve pupils in three groups:

— It is enough for now, because I need to pay attention to everyone. They are small kids, so if you don’t pay attention, you’ll have paint all over the place.

Olha has a wealth of experience with children, as she used to work as a teacher in Poltava at a children’s art school for ten years. She enjoyed working with children, but she complained about spending too much time on writing lesson plans and other red tape.

That is the reason why she took up tutoring in her own workshop. Olha is happy about the fact that even nursery school students are interested in her classes:

— They are sincere, unspoilt and uninhibited. Once they start school, they are brainwashed to follow certain stereotypes. I tell them they may draw a purple cat or green birds, just as the sky does not necessarily have to be blue. It can also be peach colored: most importantly, it should reflect one’s mood.

Olha insists that it is not the right time to teach carpet weaving to kids, as they have poor movement coordination. It makes sense to wait until they are ten years old. At first, they need to be introduced to the basics of painting, the study of colors, and composition:

— However, they see how things work in the workshop and it makes them interested. I can tell that they are eager to learn. Should I turn away for a second, they pick up something right away and play with it.

Olha also teaches the youngest generation of the Piliuhin family — Pavlyk, her eight-year-old son:

— He has such an imagination so that in his pictures flowers and birds grow on trees instead of leaves, — Olha said, showing the work of her son. — For now, I explain to him which colors are compatible and how to apply them to flowers. He also knows that the ground changes its color during the sunset.

Olha is happy to pass her knowledge to younger generations. She inherited most of her teaching skills from her father, who has more than 30 years of teaching experience. The Piliuhins believe it is important to prevent the carpet manufacture traditions from extinction and to revive this art in the future.

Olha’s works are well-recognized as she often exhibits them at expositions and in museums:

— For instance, this is my work called “Koliada”. I saw it being duplicated and used for postcards. I also saw it used for painting on glass and batik printing.

Olha is fond of her occupation. She insists that she could never do anything else. People who are unfamiliar with this profession tend to say, “You are out of this world! What is happening in your head? How can you do anything like that?!” But this art came naturally to Olha, as it is something she has been doing since early childhood:

— When I work with yarn, I feel the harmony and joy of doing what I want. I can incarnate my vision. Yarn responds to me. I really like this material and work on my pieces with love.

— I work with joy. I am unhappy when for some reason there is no access to the workshop. I want to work and create things.

All artists sell their works. Piliuhins are not an exception. However, Olha said that carpets are not really in demand, as they are quite expensive:

— Of course, I treat my works as if they were my children. Letting them go is sad, but I feel glad when my works bring joy to other people. It means, I did not do it in vain. Carpet manufacturing is my life calling. I’ve been following this path for over twenty years.

How we shoot

Watch a new video blog shot in Poltavshchyna featuring us on our way to Reshetylivka; the beginning of a story about the sculptor Valerii Yermakov and how we came up with an idea to take him on a trip to Greece (Watch a diary of his journey in Greece); and also how we were welcomed in the Mhar monastery.