Melodies of the violins created by Volodymyr Solodzhuk, the craftsman from Bukovina, are born in his small workshop in Chernivtsi. Nowadays his instruments conquer concert halls all over the world. After working as a works engineer for many years, Volodymyr turned his life around in a blink by choosing a violin with which he had become involved since childhood. The craftsman, who had been self-taught at first and then got a chance to learn from the violin guru in Italy, manufactured around 200 musical instruments each of which has its own travel:

— There are a lot of my instruments in Ukraine. Most of them are in Lviv and the rest appear around the world – in Tel Aviv, Bonn, and Hanover. The very first violin which I made is in Porto now.

Volodymyr Solodzhuk manufactures his violins manually. The manufacturing process may be compared to taking care of a small child whose voice will surely sound and pleasantly surprise everyone one day.

There are no finished violins in Volodymyr’s workshop:

— No violins. Thank God, they have been sold. My musicians have them.

Volodymyr Solodzhuk has an excellent knowledge of the violin’s structure and operating principle, but he does not play. The craftsman thinks that if you want to do your job well, you have to play well or to manufacture instruments well. It is one or the other:

— You know, if you want to run, you have to run. I can try to determine how a soundpost stands inside a violin. I can make an installation to improve instrument’s sound. A draftsman who makes Ferrari for the Formula 1 isn’t always a good driver. I can play, but it won’t be music.

Devotion to violin

Volodymyr Solodzhuk has become interested in violin since his school days. At that time, he made his own small jack plane and repaired his first violin by himself. Actually, it was a violin for children. Volodymyr gradually plunged into the world of the violin art:

— At first, it was just a hobby. I made a souvenir violin. It was as a real one in its level of detail. And that got me thinking, ‘Why shouldn’t I try?’ Someone had asked me to repair a stick, then a violin. Then I became interested and made 10-12 musical instruments. One of them was more or less appropriate, and the artist of Philharmonic put it to work.

Volodymyr had been working at the factory before he started to manufacture violins professionally. After another job cut and closing of the factory, the economist and techie by occupation threw himself into the world of musical instruments.

That was when Chernivtsi Philharmonic Hall needed a specialist in master tune of a pipe organ. Volodymyr applied for this job and completed courses in a conservatory. To him, it was the start of a vocational music education and the complete change of activity. He has been cooperating with Philharmonic Hall taking care of musical instruments for about 30 years now.

Then, one day Volodymyr’s life changed dramatically:

— During a drinks party on the occasion of getting the title “The Honored Artist” by our artist, we were offered a drink to a craftsman who made a violin for an honorable musician. He was surprised because normally the craftsman is either old or passed away. It was Friday. Early in the morning of Saturday, they called me and said, “The mayor made an appointment to meet you on Monday”. I was wondering why. “Well, – they said, – ask him for a bench or something else” Then I said that I’d like to go to study.

After this conversation, Volodymyr immediately started looking for opportunities among his acquaintances:

— I got through to a craftsman from Lviv. He gave me a telephone number of Alexander Krylov from Cremona. I called him and said that I was a craftsman from Ukraine and I wanted to study. “Okay, – he answered, – Come, but I won’t make an invitation for you. Come if you can make it.” I asked him how much the study would cost. The answer was, “As for the former compatriot – nothing.”

So, instead of a bench, Volodymyr Solodzhuk asked the local government to send him to Italy for study, and it worked:

— I came to our mayor. Then there was a session of the municipal council. They gave me 2.5 thousand dollars. At that time, it was a huge amount of money.

As Volodymyr said, the Philharmonic Hall could repay its debt for that money. It was the 1990s – difficult times when money was scarce:

— Instead of salaries, there were set-offs – costumes, vodka… Anything but money.

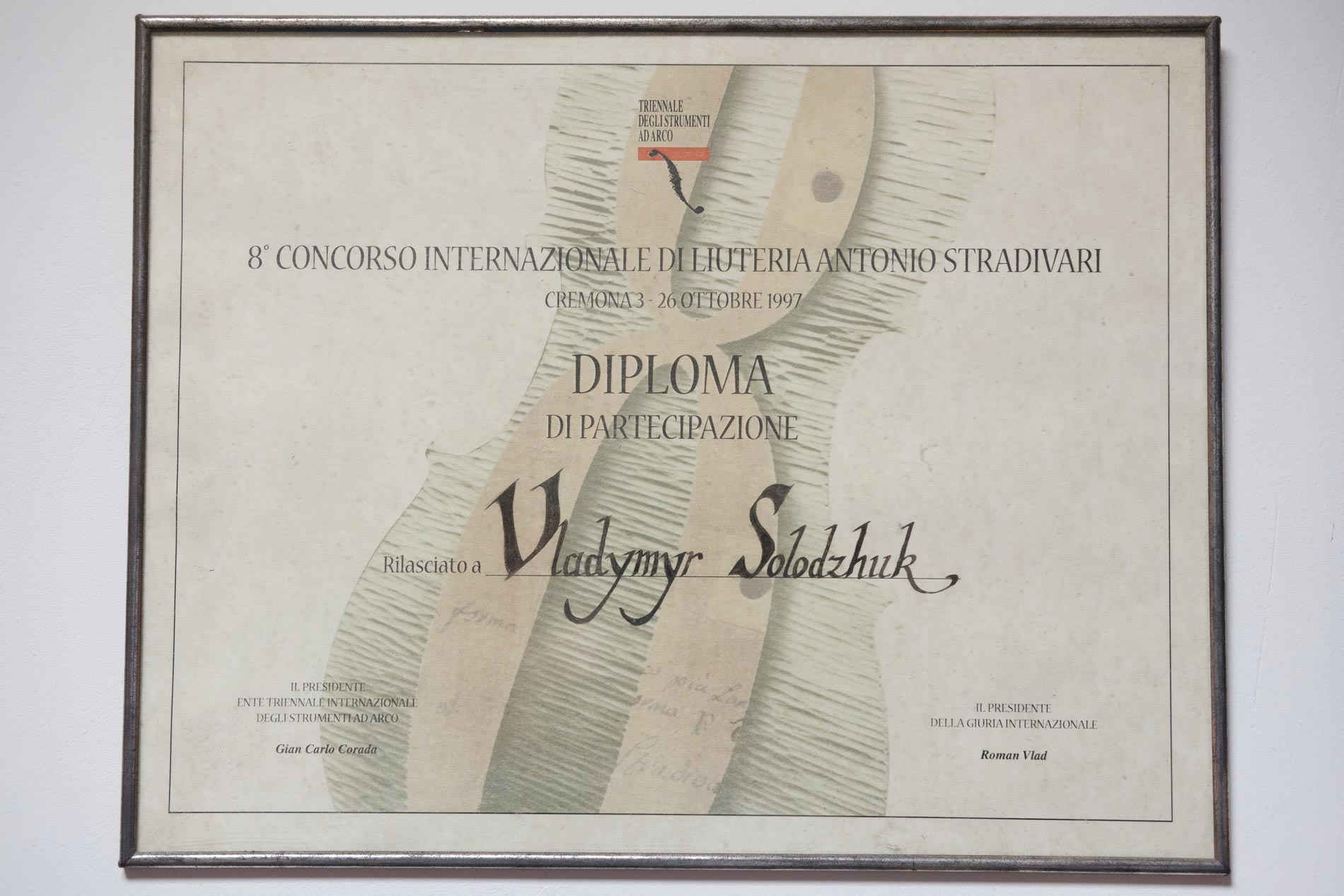

Studying in Italy

Alexander Krylov, a craftsman from Russia, became a good teacher and contributed to Volodymyr Solodzhuk’s career as a craftsman:

— Alexander Krylov was a brilliant man, a teacher who taught you in a way you were unaware of. It made you feel as if you had learned everything on your own.

Volodymyr remembers what his teacher said about the violin art:

— Becoming a violin craftsman can be compared to riding an escalator down. If you want to move up, you always need to make the next step, otherwise, you lose your level.

So, Volodymyr got into the Italian town Cremona, a home to the outstanding music craftsman Antonio Stradivari. Once he arrived, Solodzhuk started working:

— I bought a set of wood and began to make a violin. I made mine and he (teacher – ed.) made his on the same bench. It was a hands-on training. It took me two months to make a violin which sounded Italian.

Over time, Volodymyr understood why craftsman did not take money for such valuable study:

— It turned out that “nothing” didn’t mean “nothing”. There is a tradition: violin craftsmen never take money for studying. A teacher takes an apprentice or not, but he doesn’t charge fees. A craftsman’s apprentice can’t sell his instrument by himself. An apprentice is nobody, but a craftsman has a name. He can sell this instrument at a higher price. If I give my violin to the craftsman, I’ll receive more money for it, because I’m unknown. Your popularity can grow or drop with time.

Volodymyr appreciates knowledge acquired in Cremona:

— You can’t find out a lot studying on your own. I had made 10-12 violins before my trip to Cremona, but it hadn’t been even 5% of knowledge that I received there. I was lucky to live among violin masters and share the same environment.

The teacher motivated Volodymyr to upgrade his skills, taking no notice of money:

— Volodia, you know, you can be a craftsman or not. Not a big frog in a small puddle but a craftsman. It does not matter where you live – in Paris, in Chernivtsi or in a remote village. It does not matter how much money you earn for musical instruments. Today you receive nothing, but tomorrow there will be those who want to order a really good thing and can pay for it, and you won’t be able to make it. Make every instrument as if it were your last. No one will ever ask you how much you received for this instrument, but everyone will know that it’s your instrument and it’s worth its price.

Also, the teacher gave an understanding that each of us was responsible for how his or her life would turn out. He taught not to complain:

— I arrived and said, “The government doesn’t pay us.” Then Sasha Krylov gave me a good answer, “Did government order you from your mother? So, the government owes you nothing.”

— For God’s sake, let the government help ill, orphans and cripples. Other people have to earn money and pay taxes. Nothing will happen until we understand it and stop waiting for somebody’s help. Look, I take a lump of wood, it costs a little money, and I have to make an added value out of it which I’ll sell. And I have to get by on this money, pay for electricity and the rest, and buy a new material for a new instrument. And this thing must be worthy.

— Belgium, Luxembourg, England and then France were the first to buy instruments in Cremona after the Second World War. Germans started in the late 1950s. As a country develops, the need for classical music appears. Americans began to buy instruments in the 1970s, followed by Japan. In Cremona there are a lot of women who make violins. It is a popular place to study among Japanese and Korean. Then Korea made Samsung and Hyundai. What else do they need? Listen to Mozart! Nowadays Chinese are studying. There are over a thousand of craftsmen in Beijing.

Carpathian spruce

Violin’s sound quality largely depends on wood. Different parts of the instrument are made of different wood species, each of which has its own unique characteristics. That is why there is no wood type which can be self-contained in creating an instrument:

— Why spruce? Because it leads a sound wave faster than any other material. Why maple? Because a back plate made of hard-wooded species retains 27 kg cord tension for 300 years. It must be made correctly. The stuff but not the fluff. Maple leads the sound faster than any other hard-wooded species. These two breeds – a maple and a spruce – are perfect for making a violin.

Now we cannot imagine any connection between Stradivari’s violin and the Carpathian Mountains, though, this could be real:

— Our Carpathian wood, especially a spruce, is the best all over the world. It’s a very valuable tree. You can find it only in the Carpathians. There is a hypothesis that Stradivari made instruments of Carpathian wood.

Volodymyr complains that such valuable wood is sold almost for nothing:

— There number of Carpathian spruce is rather small, and people still cut down these trees. This wood is sold in the form of a round billet. Our people don’t even think of being more attentive to trees. They only care about round billet and that’s all. It’s foolish. Guess what, such piece of wood costs at least 15-20 euro in Cremona. Can you imagine it? And we sell round billets. Such piece of sycamore maple costs 120 euro. We sell a cube of it for 400 euro.

Volodymyr has his own version why fir has become so popular in the Carpathian Mountains:

— A fir isn’t our intrinsic tree. It’s good as a floorboard, but it’s full of knots and resin. They started to plant these trees after the Second World War. We know that they began to cut Carpathian trees for timber setting in Donets mines. Then the mountains began to shift, causing floods. It was necessary to cover the deforested area, so they planted Spanish fir. Now even Hutsuls think that fir is the Carpathian intrinsic tree, but it is not.

According to the craftsman, a spruce can serve not only as a material for violins:

— It’s used for all musical instruments: a piano’s string-plate, a guitar, a violin, a cello, and a double bass.

Italian sounding

Italian tradition of manufacturing a violin creates a musical instrument, sounding of which comes through the ages, so this instrument must be of a very high quality:

— There are things which stay the same for centuries, such as propolis or wax. Usually, we use such ingredients that grow soft or remain constant. It’s an artwork: each craftsman looks for something that works best for him. The main thing is to choose such material that is good and does not inhibit an instrument sound. A violinist has two hands: one is a stick, the other is a violin. So, a musician must like his instrument. You can even tell whether a craftsman is right-handed or left-handed looking at a violin he has made.

So, what makes the Italian sound stand out from the others:

— Musicians evaluate sound in different ways. But there is the axiom: tone must rise during amplitude attenuation when you pluck. We’re speaking at about 15 decibels now. But I can speak quietly and argue with you at the same time. If a Chinese was behind the curtain, he would understand that I argue with you, because the dynamics of sound would change. A good violin can do the same. I can speak with you loudly, happily, emotionally, and a person will understand it even if he or she can’t understand the language. Instruments with Italian timbre, those which tone up during attenuation can do the same. All these features have been present in Italian timbral sound. There are no fakes or accidents.

Volodymyr capitalizes on the technology of manufacturing instruments by hand which is much appreciated in the world:

— In my workshop, there is no equipment besides a saw. Everything is done manually. There are 6 chisels, planes, knife, and hands. Debugging is made with the card scraper. Everything is done to the sound. This technology of manufacturing musical instruments is 300 years old. Nowadays many craftsmen try to technologize the process, but they lose contact with wood.

Volodymyr is not very optimistic about present interest in violinmaker profession in Ukraine:

— I’ve been working in this workshop since 1999 and during this time only one person showed interest in instruments manufacturing. That’s a pity. We have become consumers rather than producers of something.

In Chernivtsi, Volodymyr Solodzhuk says, there is one more violinmaker – Volodymyr Antoniuk, who used to be his apprentice:

— Violin manufacturing isn’t traditional for Ukraine, but many violin makers have always worked in our country. Since the Soviet Union, we still have Stepan Melnyk, the violin “patriarch”, who lives in Ivano-Frankivsk. He’s one of the first Ukrainian craftsmen. In fact, in every town, there is a person who makes violins, but their number is becoming smaller and smaller. I have deliveries of musical instruments for the repair from Ivano-Frankivsk, Khmelnytskyi, Vinnytsia, Zhytomyr, and sometimes from Kyiv, but there are a lot of local craftsmen.

According to Volodymyr, there is a great difference in traditions of communications between Ukrainian and Italian craftsmen:

— Ukrainian violinmakers, for some reason, compete against each other. And, as the saying goes, it’s shameful to ask somebody. In Cremona, there are more than 120-130 workshops like mine, with 2 craftsmen in each. People came to my craftsman, tried instruments and asked, “Are there other good craftsmen?” He answered, “Everyone here is a good craftsman.”

– Sacha, why did you say it?, – I asked, – He’s not worth it.

– You know, if I said something bad about him, he would say the same about me. A client would turn and walk away. We need to grow business. All craftsmen are good, and the client will choose an instrument he wants. A craftsman will never say something bad about the other craftsman.

The demand for classical music in Ukraine

— There are Ukrainian musicians all over the world, in any orchestra. If you see somebody with a case in any European city, you can come up and begin to speak Ukrainian or Russian. You will definitely meet our people. There are Ukrainian musicians are in all European cities.

Volodymyr thinks that the lack of a strong demand of Ukrainian audience for classical music is one of the reasons why our talented musicians go abroad en masse to work:

— Our music education is quite good, but Ukrainian audience is not interested in it. Musicians often go abroad because of payment. Audience votes with its feet. Audience either attends concerts or not. If a 70-men symphony orchestra performs, there are 70 or 50 people in the hall. An organ concert takes place in a hall for 300 thousand or more people but only 15 people come. It means that there is no need in a feeling of sound.

Volodymyr makes interesting comparisons about a demand for classical music in South Korea:

— Mozart isn’t an authentic Korean music, but Koreans listen to his music, and it is very popular. For the second year in a row, our Chernivtsi symphony orchestra goes on tour to Korea for month or two. Halls for more than 2,000 people are filled with people, because there is the demand. A spiritual requirement. We don’t have any. Fancy that.

Volodymyr emphasizes that music is an important element for personal development, because it can encourage logical thinking and expand abstract thinking:

— Since Ancient Greece, whether you were a mathematician or not, you still had a music lesson, because music is much deeper. It’s a function of two brain hemi-spheres. I like an expression of Lubachivsky, the late Cardinal. He said, “What is art? It’s the yearning of soul to the lost Heaven. Who knows what you’re doing it for. What makes you write poems? People don’t pay you for it. What are you singing for? It’s a blur. We have lost this Heaven. And we don’t remember it”.