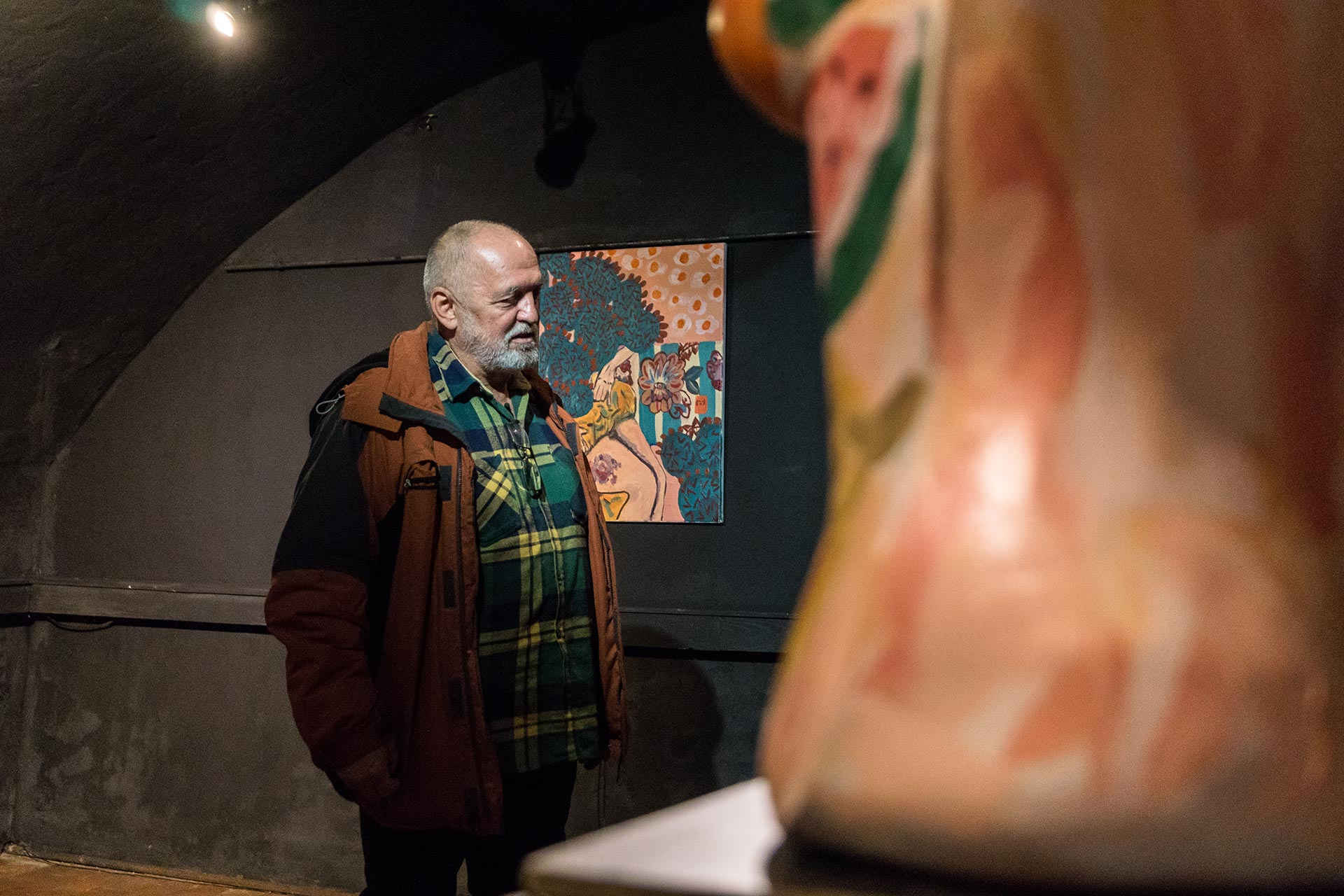

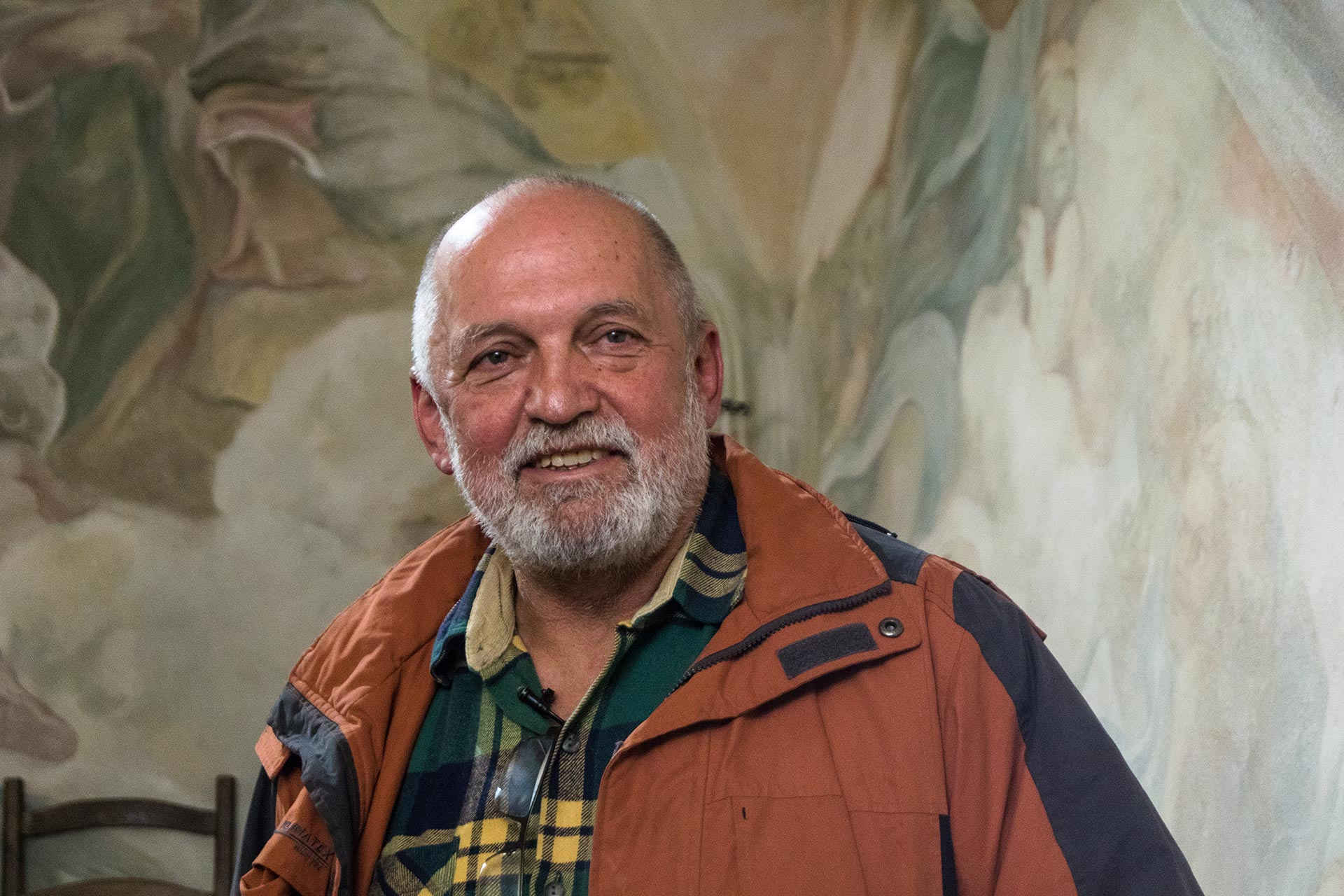

The Museum of Ideas in Lviv has always been a place of origin for various initiatives: the festival of independent movies ‘KinoLev’, the first glass foundry workshop, a gallery, a refectory and even a fictitious republic began here. The Museum of Ideas was opened in 1992 by Lviv painter Oles Dzyndra who managed to create an art center that has been involved in art experiments for more than 25 years.

The Museum of Ideas is located in the center of Lviv on the premises of the former brewery of the Bernardine Monastery cellars. Initially, the idea was to create a museum of glass, but the poor condition of the vaults made it impossible. In 1996 the Museum of Ideas opened its showrooms:

— Borys Voznytskyi passed along the keys so that we could create a showroom of the Museum of Glass but the conditions were horrifying and the collection was handed over to the National Museum (The National Folk Decorative Art Museum — ed.). There was knee-high standing water. All the cellars were like that. (There are more than 400 square meters of basement premises.) We stayed here, changed our area of specialization and fought the dampness and the water for almost 10 years. The water wasn’t such a challenge, but it was actually the fungus that kept us from holding exhibitions and having visitors here. It lasted for years. We took out around 15 lorries of mud.

Nowadays the big collection of old foundry glass from the 18th-19th centuries is kept in the National Folk Decorative Art Museum in Kyiv. In 2006 in Lviv on the Rynok Square the Museum of Glass opened, founded by the famous glass artist, Andriy Bakotey. The museum is a branch of the Lviv Historical Museum.

Today the Museum of Lviv holds exhibitions, concerts, performances, theatrical exhibits and other art events. Despite its fraught history the founder himself doesn’t take up the challenge of defining his project and calls it a utopia:

— On the one hand, I am simply joking. On the other hand, it is one of Lviv’s utopias that survived. You see, the Museum of Ideas is 27 years old and is still afloat. The utopia lies in the fact that it is a self-created, self-sufficient culture project. We earn the funds that we later invest in some cultural project.

Foundry glass

The history of foundry glass production in the territory of Ukraine is rooted in the times of the Principality of Kyiv Rus. Back then there was a tradition of small artisan productions to decorate purely functional items like decanters, bottles, and shtof-bottles with moulded braids, bands and threads. In the 17th-18th centuries among the peasants were popular big glass barrels, basins and dishes for grain and flour storage; decanters, shtof-bottles and jars of different shapes for liquids. The drinking vessels were no less diverse: goblets, shot glasses and cups. The prime of foundry glass dates back to the 18th century. We have more well-preserved samples from that time. Since the 19th century, the popularity of foundry glass plummeted due to the appearance of glass factories. Mass production slowly displaced the artistic element:

— In Soviet times, Lviv was the capital of glass production. There is a legend that glass manufacturing existed here prior to it. Well, actually it did, but it was in the Middle Ages and thanks to particular patrons. There were Skoliv glass craftsmen, and later on Zhovkva glass craftsmen. There was a famous factory ‘Rayduha’ here. The cut glass stopped being popular and the factory got penalized for fluoro-phosphorus emissions in the city center, so they closed down and went bankrupt. Our factory (Lviv experimental ceramic-sculpture factory — ed.) was created in the 1960s as a part of the art fund. The art fund was part of the Union of Artists. The Union of Artists was a creation of Stalin. So it was funded by the state the whole time. When the Soviet Union collapsed and we were exposed to the free market, the club-like state institutions like the Union of Artists — I call it a club because I can’t call it anything differently — it was uniting people according to their profession, but began to collapse due to lack of economic sustainability. They all got used to coming to their workplace and receiving royalties for some samples they had created, then they would get some bonuses from the Kyiv authorities, and then some author’s fees from Moscow.

“The Lviv art community had to adjust to new circumstances after the collapse of the Soviet Union and a big number of industries weren’t able to deal with a challenge like that,” tells us Oles Dzyndra. However, there were exceptions:

— Everyone in the Soviet Union envied Lviv artists. They could create samples, they could fulfill some monumental orders and live in great style. Lviv artists were the first to purchase Volga cars (an executive car that originated in the Soviet Union. — tr.). However, everything changed with time and they had to pay for all resources: for gas, for instance. They couldn’t steal or sneak something out. Everything has changed now. A lot of self-sufficient people were not able to change, because they had never experienced that; they weren’t able to adjust. Adversity is a great discipline. Those of them who managed to adjust were able to survive and are known as good managers and glass artists.

Art communities of glassblowing and ceramics, for example, were able to exist due to the fact that along with works of art they produced sculptures of the Soviet party leaders and thing alike:

— Both near Riga and Kyiv there were hubs like that. There were a great number of them but they simply died out since they were stillborn, because they were state-supported artistic unions and part of the ideology. Besides our glass and ceramics, there was a sculpture workshop that had to produce 40 sculptures of Lenin a year. So that’s how it worked. But along with that the notion of Lviv ceramics as an art form appeared. Not just some pots but an art form.

The Museum of Ideas houses permanent exhibitions of foundry glass. Foundry glass represents a special kind of decorative and applied arts, the original processing of glass in a hot state. It is an old production technique. In the process, each item comes out unique and there are no two alike. Oles Dzyndra explains:

— No matter how hard we cannot reproduce two identical items. There are supporting wooden moulds and some metal tools, but the item always comes out slightly lop-sided, warm, stout, and different every time. And it’s mainly because it is handmade. That’s the charm of this glass.

Oles has been creating foundry glass for more than 20 years although he is an architect and painter by education. He says that he likes glass and that’s why he got involved in production since nobody makes foundry glass anymore. His interest in foundry glass began from a sculpture ceramics factory where he designed monumental items and after a while he began working with ceramics:

— I liked working with glass because there is an immediate result while in ceramics you need to shape something, fire it, paint it and fire it again, mount it, and it is all time-consuming. While glass makers just scoop some liquid glass and either something beautiful comes out and then you do a great job and the Italians call it “a la prima” (“from the first time”). And since I am a hot-tempered person I like when things come out right on the first try. Foundry glass can’t be put aside and worked on later. If you don’t finish the item while the glass is still hot (which is about 40 minutes to up to one hour), everything will turn into garbage.

There is the main oven where the glass is melting. We melt transparent glass all the time; the colored glass that you see at the foundry was prepared earlier. It is not colored with paint of some kind; it’s the glass itself. The temperature you need to make it is 1300 C, and it is made from transparent glass. There are a lot of technical nuances for the colored glass to be durable, such as ratios and chemistry. It is a concurrent specialty that a glass craftsman has to learn, or else the glass items will simply fall apart. When an item is ready it is put into an oven to cool down for a day to reach room temperature. Cold glass finishing tempered glass. The next step would be polishing, or maybe drilling a hole, and that’s it.

Oles Dzyndra works with two other craftsmen, who come from the factory, and his son, a professional artist-glazier. Oles calls his colleagues “the last of the Mohicans” since there are no other foundry glass makers in Ukraine, though the Lviv National Art Academy has a major in artistic glass foundry. Students from the Academy and abroad come to Dzyndra’s foundry to do their graduate work.

— There is an artistic foundry in the Academy of Arts in Ukraine. There is one in Lithuania, but the one in Moscow is already dead. Their students come to work on their graduate work here. There are a lot of factories that produce cheap glass, especially in China. Those factories are part of the industry, and an artist has nothing to do there. He can just come up with a shape and they will produce it in bulk.

slideshow

Nowadays, there is an association of glassmakers in Ukraine that unites factories producing glassware for the needs of the food industry: bottles, jars and the like. There used to be 20 factories in Ukraine and now according to Oles Dzyndra there are just 10 since Chinese glass is much cheaper.

— There is mass-produced glassware. Machines and robots do the job. For instance, bottles are produced like that. There is cold glass finishing, and there is well-known stained glass, though the base for stained glass is also produced at a foundry. They blow out (they call it the easy way) big cylinders, decorate them, cut them up and melt into sheets. Then they make a stained glass window out of them. So everything is connected to foundry production. It is an archaic fundamental institution that is in the foundation of any glass making.

Decorative artistic items from foundry glass are highly valued in the world. At Dzyndra’s foundry, they have produced hundreds of different art objects: false ceilings, lampshades, glasses, interiors for restaurants with foundry glass design themes and such. They used to export their works to 28 countries such as the USA and Japan. Oles Dzyndra recalls:

— I was excited like a child recently when I was watching a Hollywood comedy and saw my clown figurines on the shelf of the movie set. We were exporting them for 12 years.

However, nowadays the majority of the art pieces are sold in Ukraine. Oles Dzyndra connects the increase in demand with the development of the aesthetic taste of Ukrainians, though they buy mostly household items:

— People have already traveled a bit and can afford more things. The only thing is they don’t buy expensive artistic works but rather decorative items, for everyday life and not very expensive, but it’s enough for the foundry to keep going. You can make just a couple of items and then wait another 20 years to sell them.

The foundry craft has been preserved in a number of European states. For instance, in Sweden, France and Germany there are a dozen small foundry productions. They get support mostly from city halls or other state institutions compensating them for their utilities expenses. The foundry owners closely cooperate and often visit each other to exchange experience or organize common projects.

The Museum of Ideas

In over 27 years of existence the Museum of Ideas has organized over 800 art events and more than 30 city and national art, environmental and social projects: the cinematographic festival ‘KinoLev’, the open-air exhibition of foundry artists ‘SkloKoko’ and ‘Days of Croatia’ in Lviv, to name a few.

The Museum cooperates with foreign cultural institutions and is one of the co-founders of Jarmark Jagielloński in Lublin, Poland.

— It was founded by three institutions: the Lublin Town Hall (Poland), the Brest Town Hall (Belarus) and the Museum of Ideas. The Fair keeps working though we don’t take part in it anymore, we are guests of honor on a regular basis. We launched it 6 or 7 years ago.

The Museum of Ideas is one of a kind. There is a museum in Barcelona with the same name but it is dedicated to inventions while Lviv Museum of Ideas highlights abstract ideas and tries to convey it in the exhibitions held in the Museum:

I prepared a bizarre exhibition, people attending it were shrugging their shoulders. There were tables with more than 300 three-litre jars with covers. That’s it. They were all empty. And when they asked, “What is it?” we were answering, “There are ideas inside.” Here is one, here is an idea about this, there is one about that. Because we can’t explain the nature of an idea, and we can’t promote an idea since we ourselves don’t know where it comes from.

According to the artist’s opinion, creativity is about a sense of harmony and ability to separate out the superfluous and keep the essence:

— To find a proportion between them, I mean, how much to cut off a stone slub, a little bit more or a little bit less, and not to leave anything out is a talent. The same rule works when you are in the kitchen. You can’t teach creativity at educational institutions or at home. It makes up part of you, otherwise you can’t function. You think up something every single day, every day you think up some crap, crap you believe in. Whether it comes out the way you want or not, that’s not important, I believe. Creativity is a process.

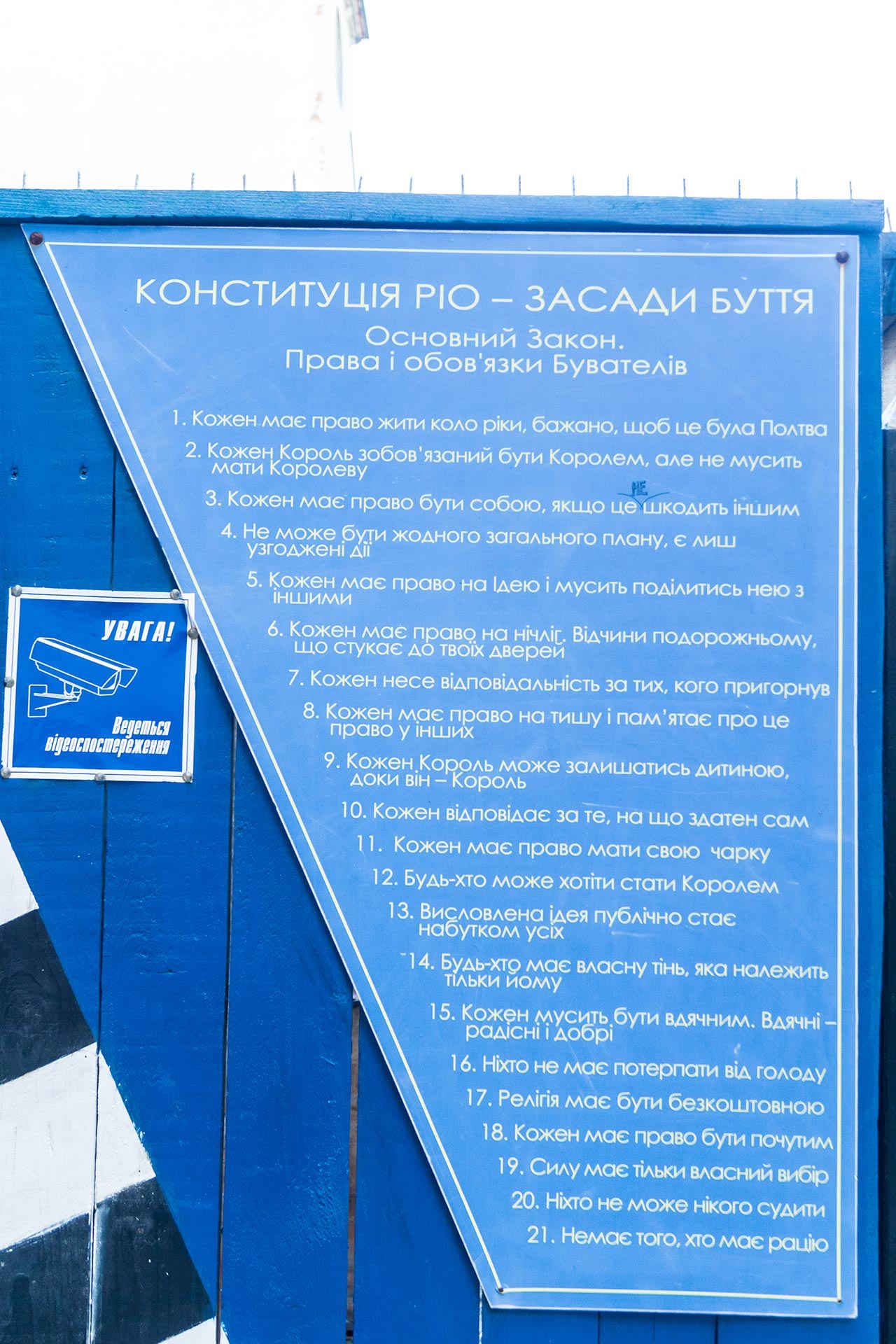

One of the museum’s ideas is RIO, the Republic of Ioania. The Republic is a union of artists and according to Dzyndria entertainment for adult scientists. It ironically claims as its territory all shadows that exist in nature. The Republic does not aim at creating its own state, but rather it is a club of like-minded people who can generate ideas together:

Obviously we don’t print our own currency and don’t fool around with statehood with a flag, but during our parliament sessions we can model seemingly absurd ideas, but when you look into them you will say: “Gosh, why don’t we have something like that in Ukraine. It’s so simple!”

The Museum of Ideas is one of the founders of a large scale Biennial of Trust project, that was initiated a couple of years ago at meetings of active Lviv citizens and intellectuals and transformed into a full-scale project:

After Charles Landry (the founder of the Biennial of Trust — ed.) came to Lviv he suggested a very good project: to transform our meeting into a citywide project. We will conduct it every two years. Hopefully it will keep going. In a year we will hold it with our partners in other European cities.

Oles tells us about the first experience of holding the poster contest as a part of Biennial of Trust in 2018:

— It is an international contest. We were ambitious when launching it and expected that intellectuals would react to the idea, “What is trust? How do we fight the trust crisis?” In two months to our amazement we had almost 500 posters.

The Museum of Ideas joins other social city projects. The museum initiated the creation of the River City organization that aims at restorating the river Poltva in Lviv (currently the river is locked in an underground tunnel — tr.). For three years the Museum of Ideas was co-organizer of conferences and workshops dedicated to the problem of river restoration:

— It is a social disaster. It is an issue of moral health, of Lviv citizens’ health. If we are fine with the fact that our springs and our river — the only river — were turned into a sewer then it will stay that way. But if we all believe that it’s immoral and all of us will stand up to protect it, the river might revive. It is a typical practice in many European cities — and not just European ones. For instance, in Seoul, Korea, they saved a river, and now it flows clean on the surface.

Refectory of Ideas

The ideas in the museum can not only be seen or reflected on but also tasted thanks to the Refectory of Ideas. The idea to open a place like that arose accidentally. Oles recalls that during one of the festivals an unexpected thing happened: sponsors backed out from the event and the organizers had to cook for themselves and eat off their laps. The guests loved the food and after a while, the Refectory of Ideas opened. Its small kitchen works around the clock and offers over 100 traditional Halychyna dishes. The kitchenware of the Refectory is handmade, only ceramics and glass. All glass is made at Oles Dzyndra’s foundry and the ceramics are made by his friends. The artist says that since the premises used to belong to monastery cellars and bears imprints of bygone times the founders behave there accordingly and support the traditions of common monastery refectory. The Refectory of Ideas appears in the Top 10 of the best Lviv restaurants according to TripAdvisor. According to the creators of the Refectory, the creations of Halychyna cuisine should awaken in tourists an interest in exploring local gastronomic tastes and traditions:

— We decided to create a controversy and to turn to our traditions that have great unique features and advantages. People gave us great feedback. They like it, especially foreigners. On the one hand, it’s our tribute to our traditions, and on the other hand, it is a way to promote our identity.

Not an enterprise

The maintenance of foundry furnaces is quite expensive. The production can’t be stopped because of the specific nature of the technology. The foundry furnace heats up to 1300 C and operates at this mark. To bring a furnace to the required temperature one needs two weeks, and another two weeks to let the furnace cool down. That’s why it is cheaper not to switch the furnaces off. They wear out on average in five years.

Oles Dzyndra explains the success of the enterprise by the ability to balance things and treats his business with enthusiasm:

— It has a lot of peculiarities but the most complicated thing is whether you give yourself to the fullest and how well you understand the market. If you give yourself over to what you do you will get feedback. If you don’t do it, everything will collapse and perish. Everyone wonders how it is possible that my foundry keeps working after so many years. The answer is simple: you need to balance, to balance between expenses, the market and human relationships — and it is not that easy. But due to this balance, it is possible to survive.

Mass production at the foundry Oles Dzyndra considers as a tool to realize artistic projects. For instance, the profit from the foundry and the Refectory of Ideas supports the existence of the Museum and its creative events:

— I have to do certain things out of necessity in order to realize creative ideas. I am not sure you can call it production. I can’t call it a success. I am not a business person, which is why I spend today what I will earn tomorrow, and this cycle repeats all my life, though I never borrow money. I can’t save or put aside some money because some idea always pops up and I need to realize it at once. “Give me some money, I will return it tomorrow!” and I start working on the idea.

According to Oles handmade items are more and more valued in the world because mass production of similar items is overwhelming and people look for authentic emotion and pay attention to unique and handmade items:

— For instance, there is a music industry but all of us like to listen to something live right next to us, to live singing or live guitar, right? The same here. And it makes a difference. There are production and replication, and at the same time, there is something unique like a piece of a soul that you can put on the table or window sill. People need things like that and everything depends on the background and level of culture. If they have it then there is demand. If they don’t then they don’t strive for anything. You can buy and drink a shot of vodka, or you can drink it straight from the bottle. If there is a drinking culture then you look at the shot glass and taste what’s inside. And you enjoy the process.