Greeks have lived on the territory of modern Ukraine since antiquity and consider themselves an autochthonous people. Countless remnants of ancient Greek civilization exist in Ukraine such as Olbia, Panticapaeum, and Tauric Chersonesus. Later historical Greek landmarks date from the Middle Ages. Between 14th and 15th century even a political state called the Principality of Theodoro, inhabited by Greek speaking Crimean Goths, existed in Crimea. As a result, a distinct Greek community formed on the Crimean peninsula. Later they resettled to southern Pryazovia and since then they have been known as Mariupolitan Greeks. Today the descendants of these people make up almost 85% of the entire ethnic Greek population in Ukraine. They cherish their unique culture and endangered regional Greek dialects.

A long-established tradition amongst Crimean Greek Christians and mainland Greeks is to gather all members of their communities in order to celebrate Panayir, a religious holiday dedicated to the patron saint of the local church. The celebration begins with a Church service, after which everyone can enjoy various ethnic dishes and music. Entertainment includes different activities like obstacle courses on horseback along with traditional Kourés wrestling tournaments.

In 1988 Soviet Ukraine the Greek poet and composer Donat Patrycha, from the Pryazovia village Maloianysol founded by Greek immigrants, first organized “Méga Giortí”(“The Big Holiday”) — a festival celebrating Greek culture. Méga Giortí united not just the Greek community but also all the other ethnic minorities living in Pryazovia. Since then the festival has been held every other year (earlier it was annually) in a different city in order to include all places founded or still populated by Greeks in Ukraine. The previous Méga Giortí was held in Maloianysol; this year it will be hosted by Volnovakha.

Kourés

The national traditional wrestling of the Turks but Greeks also consider it part of their culture and traditional heritage. Kourés, a type of belt wrestling, must take place on grass. Most holiday celebrations and festivals end with a customary Kourés competition.

It’s not just Ukrainian Greeks and other local ethnic groups who go to Méga Giortí, even Greeks of Pryazovia who have since immigrated to Greece return to Ukraine for the festival.

Méga Giortí celebrates Greek culture based on the traditions of Panayir, but takes out the religious component of the original holiday.

The festival begins in the morning with a traditional holiday procession, every Greek community represents itself in this march. A concert and fair follow and national dishes are served. Alongside these main events are a variety of exhibits, competitions, and presentations.

slideshow

Since Greeks of Pryazovia live close to the demarcation line (between government controlled and non-government controlled areas of Ukraine) from where gunfire can be heard continuously; the festival’s sense of communal belonging has become even more important.

The Festival of Méga Giortí is a testament to the revival of Ukrainian Greek culture despite their checkered past which includes forced resettlements during the time of the Russian Empire and oppression under the Soviet Union.

Bohdan. Music

Bohdan Samko is a Pryazovian Greek. Bohdan learned about Greece and traditional Greek music already as a child at music school. Bogdan remembers learning about the rich musical culture of Priazovia Greeks sometime later:

— After graduating from university, I was watching a local television channel where some older musicians were talking about how the Greek musical tradition in Pryazovia was dying out. So I thought about it and then decided, “Why not do something about this if I can?” I told my friends, “Come on, let’s start playing our music!” All agreed. So that’s how it all began.

Today Bohan collects local traditional music and has his own musical ensemble “Ochtras” which translates as “abruptly”. They say that they unexpectedly burst onto the Ukrainain Greek cultural scene when a revival of their local traditional music seemed impossible.

There are six members in the ensemble and they all play traditional Greek instruments such as the daire, a tambourine, and the davul, a double layered bass drum made from either lamb or goat skin. They also have three violins, two clarinets, and a harpsichord.

For Greek Ukranian culture to continue its development, youth engagement is vital. On this front, Bohdan is excited and hopeful since he sees how the youth in his area are taking an active interest in preserving their ethnic national traditions by singing traditional songs and learning to play the music. Musicians have even begun to remix traditional Pryazovia Greek tunes into contemporary music.

— Right now there is a reemergence of music in my opinion. I simply do what I can. It’s something I cannot live without. That’s it. The cultural revival began after the fall of the Soviet Union. A lot began to happen after the Soviet Union broke apart.

They don’t only play Greek music, but also Ukrainian and other ethnic folk melodies. Bohdan strongly believes in treating all cultures with equal respect and not only focusing on your own:

—Ukrainain music is pretty energetic and cheerful with refrains like Hop-tsa! Dryp-tsa! Op-tsa-tsa!, or the Kolomyiky (a widespread and popular short song form used in humorous folk songs) and the hopak (a traditional folk dance). In contrast, Greek music is… have you seen the syrtaki? It’s a bit slower. Our [Pryazovia Greeks] dance is the haitarma. This dance only has one movement, so it’s interesting.

haitarma

A national dance shared by the Greeks of Crimea and the Crimean Tatars.

Bohdan’s wife is also Greek and at home they speak a mixture of Ukrainian, Russian, and Greek. For them it’s important to remember that they are Greek. But all the same Bohdan is proud to call himself a Ukrainian. Though his village Nikolske is near the warzone, he has no intention of moving to Greece or even resettling elsewhere in Ukraine:

— I was born here and I will die here. It’s simple, I’m a Ukrainian. I was born in Ukraine and I live here. It doesn’t matter what someone’s ethnicity is. And that’s all there is to it.

Pryazovia Greeks live in towns and villages around Mariupol, the Greek city established by their ancestors, and make a concerted effort to revive their culture.

Greeks in Ukraine

The earliest archeological evidence of Greeks inhabiting the territory of modern Ukraine dates back to the 7th century B.C. Already by the 6th century B.C they had founded the towns Olbia, Panticapaeum (now called Kerch), Tauric Chersonesus (today’s Sevastopol), and Caffa (now Feodosiia).

A considerable amount of Greek cultural and historical landmarks have survived since the Middle Ages in Ukraine such as the cave city near Bağçasaray and the fortresses in Kerch, Sevastopol, Bilhorod Dnistrovskyi (or Akkerman) amongst many others.

An ethnic Greek community began to form in the area during the Byzantine period, this community would later be called the Mariupolitan Greeks.

slideshow

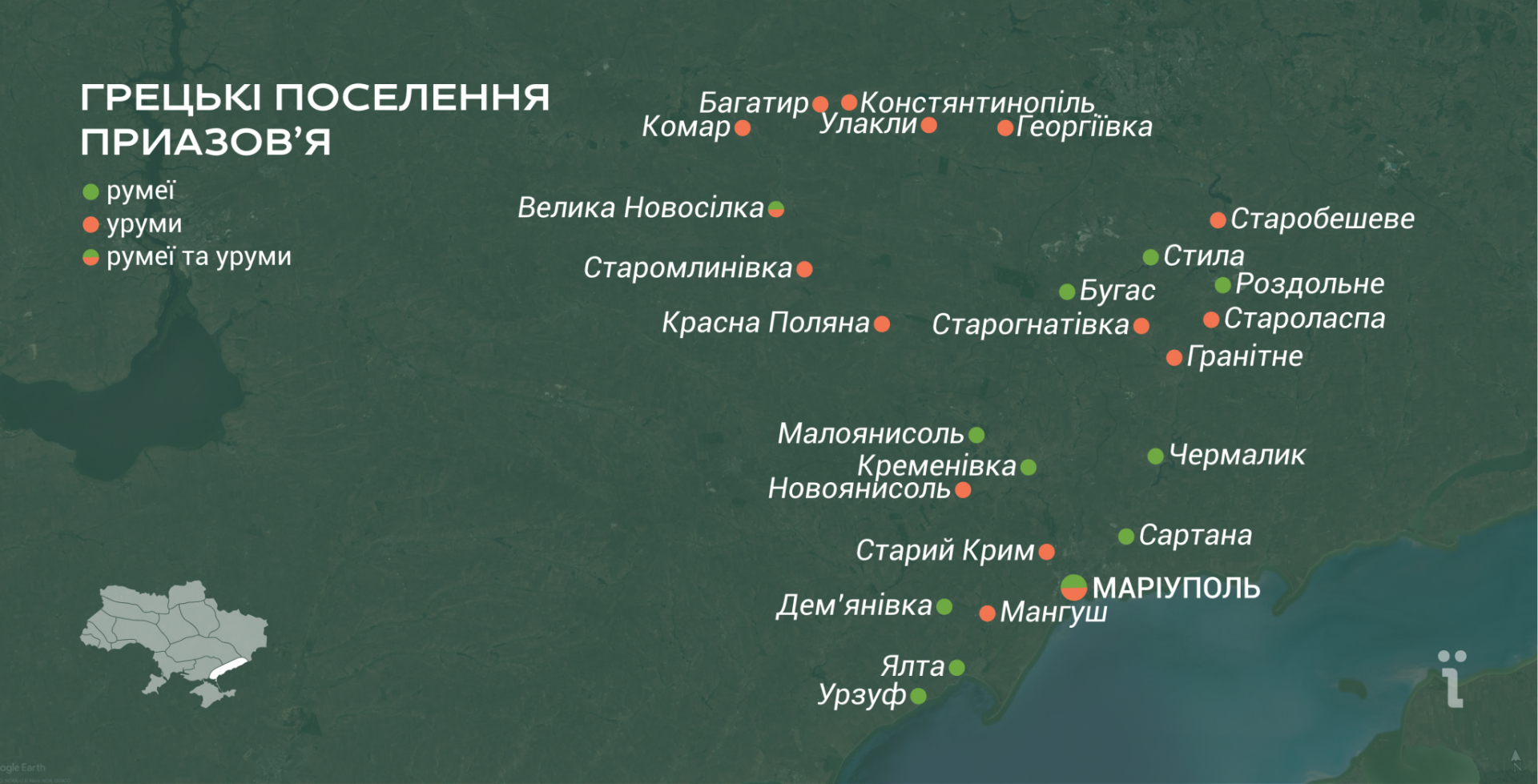

From 1778 to 1780 the Russian Empress Yekaterina II (Catherine the Great) resettled the southern coastline of Crimea along the Azov sea with four Christian ethnic groups: Greeks, Wallachians (Romanians), Armenians, and Georgians. Historical hypotheses suggest that this resettlement was ordered so that the Russian Empire could populate territory liberated after the dissolution of the Zaporizhian Sich and set the stage for the Russian Empire’s annexation of the Crimean Khanate five years later. This is how the descendants of the Byzantine Greeks — numbering over 18 thousand and spread over 80 different areas in Crimea — came to leave their homes and move to Pryazovia, founding 20 villages and the city of Mariupol as they did so.

The Greeks who established the village Nikolske, where Bohdan Samko lives, modeled it after the Cossak hamlet Hladkyi:

— When the Greeks came to Pryazovia they founded Mariupol. Everything was just wild steppe before that. Nothing was here. Except for a few Cossack fortifications. And then 22 or 23 different Greek settlements grew around Mariupol. That’s how we came to be here.

The villages were named in honor of the Crimean cities from which the Greeks were forced. Mariupol became the unofficial capital of Pryazovia Greeks and so they began to call themselves Mariupolitan Greeks.

While Byzantine era Greeks resettled in Pryazovia, new Greek migrants, this time Greek soldiers, came to the modern territory of Ukraine. And again at the beginning of the 20th century another migratory wave of Greeks from across the declining Ottoman Empire moved to Crimea, Melitopol, and Odessa. There were almost 100,000 Greeks in Ukraine at this time.

The experience of ethnic Greeks during the founding years of the Soviet Union mirrors that of many other ethnic minorities. During the Civil War (1918-1921) they were charged with allying with Nestor Makhno (commander of an independent anarchist army in Ukraine in 1917-1922), then later fell victim to “rozkurkulennia” (or dekulakization — confiscating of property from farmers and establishing collective farms in the 1920s – 1930s) policies, and then endured the famine from 1921-1923. In the 1930s another wave of repression hit, and during WWII organized persecutions (referred to as the “Greek Operation”) included mass deportation of Greeks accused of collaborating with Nazis and considered “enemies of the nation” as a result. However, during the German occupation Greeks primarily continued to practice their traditional trades. Simply working was considered “a betrayal of the USSR in support of the occupiers’ economic development.”

Today there are almost just as many Greeks in Ukraine as a century ago. According to the 2001 census, 91.5 thousand people identified as ethnic Greeks, this number has since increased to over 100 thousand people. Ethnic Greeks live throughout all of Ukraine including Prychornomoria, Tavria, and Sivershchyna. But the most concentrated population resides in Pryazovia.

Vasyl. Poetry.

Vasyl Papazov’s entire family was born in Pryazovia. His grandparents even studied Greek at school, since up until 1941 Greek language has been studied at schools. During the Khrushchev Thaw his parents also had the opportunity to study their native Greek language at school.

—When I started school, I didn’t know any Russian at all — I only knew Greek (specifically Rumeika, the Mariupolitan Greek dialect). Everyone around me only spoke Greek. All the kids, all the parents. Everything was in Greek. Of course my parents understood Russian. But amongst the kids we all spoke Greek.

At school he had to learn both Ukrainian and Russian. The irony is that now it is his children who do not know Rumeika. They can understand if someone speaks to them, but they can not respond.

Vasyl is a professional freestyle wrestler. He was a wrestling coach for 25 years and lived this entire time in Nikolske (during Soviet times the village was called Volodarske). In 1997 he decided that it was time to return home, to Maloianysol:

— The nature around me inspired me to begin writing. I began with little comical stories. My first was a humorous piece about my neighbor and everyone liked it. So I wrote more. And eventually I began to explore more adult themes. I wrote originally in Greek (Rumeika) and then Russian. That’s how it all began.

Recently Vasyl visited his native Greece for the first time.

— I was drawn to go since I never had been there before.

In general Ukrainian Greeks don’t call Greece their native country, you’ll rarely hear them use the word “homeland” in reference to Greece. They are more concerned with restoring, preserving, and reviving the local Greek culture they have.

He didn’t have a desire to stay in Greece. For him, home is better.

— How many years have I lived in Ukraine! How could I move? Everyone from my family who has moved to Greece has since moved back. No matter how difficult it is to be in Ukraine everything here is familiar. Here I live near a river, a garden, and a vegetable patch. Everything here feels like home.

From the 1980s to 1990s, Greece gave Greeks from Pryazovia the right to emigrate from the Soviet Union, and a part of the Ukrainian Greek population did choose to move. For those who decided to remain in the Soviet Union, the Greek government proposed to receive official certificates verifying their status as ethnic Greeks. In Vasyl Papazov’s Soviet passport, his nationality was stated as “Greek”.

The Language of Pryazovia Greeks

As a result of assimilation, Greeks of Pryazovia partially lost their language, culture, and traditions. Their own culture evolved as they absorbed the influences of the Crimean Tatars, Armenians, Georgians, Belarusians, Russians, and Ukrainians who they lived alongside through various periods in history. The distinctive culture of Mariupolitan Greeks is both the result and the evidence of their diverse and rich history.

Because of the planned and forced assimilation policy under the Soviet Union, today Greeks of Pryazovia speak primarily Russian amongst themselves even though they have their own native languages, Urum language and Rumeika. And from these multiple distinct dialects developed; at one point every single Greek settlement had their own local dialect.

Rumeika is the language of the Rumei, who are Greek-speaking Greeks. Experts believe that although Rumeika is considered a Mariupolitan dialect of Modern Greek, it can be considered as a separate language called Crimean-Rumeika. Rumeika was heavily influenced by Bulgarian and Turkic languages and later also absorbed many Ukrainian and Russian words.

Urum (called Urum Dili by native speakers) is the native language of the Urum people, who are Turkic-speaking Greeks. The Greeks who emigrated from the Ottoman province of Anatolia had formed as a separate ethnic group within the Byzantine Empire during the Middle Ages. While living in Crimea they assimilated with local Crimean Tatars and Turks. As a result, Urum is considered a member of the Turkic language family and Turkophonic Greeks can easily communicate with Crimean Tatars and Gagauzes.

Public schools don’t teach Rumeika or Urum within the standard curriculum, these languages are offered as optional elective courses for now and in fact neither language has an official registered alphabet. Olexandr Rybalko, an ethnologist and linguistic researcher, explains:

— Schools everywhere teach Modern Greek. In all villages inhabited by Urum and Rumei. Yet Urum and Rumeika are excluded from any official usage. These languages pop up in the published works of local poets or in the singing festivals. But that’s it.

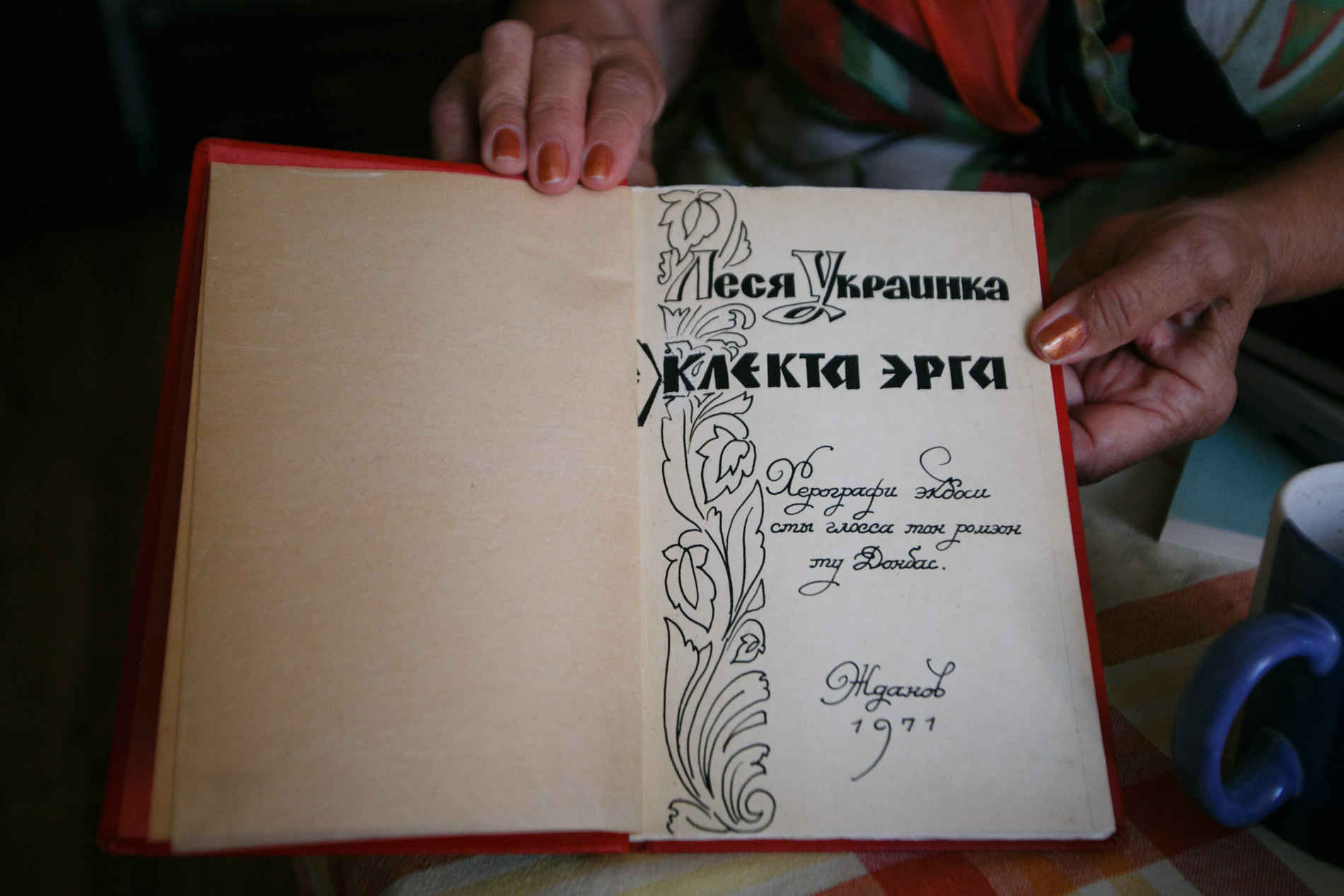

In the past, local Turkophonic Greeks wrote in Karamanli (Karamanlídeia grafí), a script using the Greek alphabet. During the Soviet Union, they were forced to switch to the Cyrillic alphabet and continue this practice up to the present.

When Pryazovian Greeks travel to Greece, they have to resort to speaking English or relying on hand gestures to communicate with mainlanders — Pryazovian Urum and Rumeika are that distinctively different from Modern Greek.

Rumeika is fairly similar to Ancient Greek since when the Pryazovian Greeks migrated from Crimea , Ancient Greek was still being spoken in Crimea. Pryazovian Greeks brought Ancient Greek to Ukraine. Bohdan, a native speaker of Rumeika, explains:

— What a mainland Greek speaks and a Pryazovian Greek speaks — it’s like if you took a Ukrainian who doesn’t know Russian and a Russian who doesn’t know Ukrainian. It’d be like that. Some of it you’d understand, some of it you wouldn’t.

In the 1930s there was a brief period when the Soviet Union supported the cultural revival of national minorities. Just as Ukrainians had the chance to develop their own culture, so too did the Pryazovian Greeks.

During this time the Greek poet Georgii Kostoprav, known as the founder of Rumeian literature, established a literary group. Other Greeks began to compile a Rumeika dictionary, but as befits the following reactionary period of repression known as the “Executed Renaissance”, this dictionary was never published — it was destroyed and all other manifestations of national consciousness were banned. Even studying Greek was prohibited.

The NKVD “Greek Operation” lasted from 1937 to 1938. During this time, 20 thousand Greeks were detained, and at least 3 thousand were persecuted on fabricated charges of espionage and counter-revolutionary activity. Amongst the Greeks were many members of the intellectual elite: teachers, actors and directors of the Greek theater, scientists, and poets, all of whom were executed. Georgii Kostoprav was among those shot.

During the Khrushchev Thaw, poets and writers began yet again to revive their Greek language, culture, and traditions. Poetry is the best and perhaps the only way to preserve a language and revitalize literary activity.

Thanks to such poetry, Oleksandr Rybalko learned about Pryazovian Greeks and began to study their languages:

— It was in a bookstore in Donetsk where I, for the first time in my life, came across a collection called “Pirneshu Astru”. I thought, ‘What is this?’. Pirneshu Astru means morning star. It was a collection of poetry from Nadazovia (northern Pryazovia) written in Rumeika and Urum. I took the book, I was fascinated, what was this “Pirneshu Astru” written in Cyrillic.

NKVD

Soviet’s interior ministry.

Mykola. Sheep

Mykola Zimbil lives in the village Katerynivka. Mykola is a chaban, or in other words, a shepherd. His grandfather was a shepherd, his father was a shepherd, and if it was up to Mykola, his own son would follow in the tradition and also become a shepherd. Mykola says that sheep-breeding was a traditional means of livelihood for Greeks and that when Greeks resettled to Pryazovia they even took their sheep with them.

The flock that Mykola watches over belongs to the residents of the villages Maloianysol, Truzhenka, and Katerynivka. He has been shepherding for over 10 years and jokes that if people trust their sheep to someone for that long, then you know they can be trusted. There are about 1200 sheep in his herd of which only 350 belong to Mykola and the other shepherds who work with him.

— When I find out that someone is a “chaban”, well, I mean when they take care of sheep, then literally after the first “hello” I know that we understand each other. I respect them three times more just because they take the sheep out to pasture. You know?

slideshow

The shepherd’s working day begins at five in the morning. He drives the sheep out to pasture, herds them all day, and then brings them home late in the evening. The grazing season lasts as long as it is warm and ends when the snow is knee deep.

During the winter the shepherds can warm up in their shepherd’s hut. In contrast to Transcarpathian shepherd huts, the ones in Pryazovia are little rooms for resting but not sleeping. Traditionally these rooms have soft wide sofas. These sofas are covered with sheepskins so that the shepherds don’t freeze.

Lamb is always the main meal for local Greeks, Mykola says. There would be no holiday without lamb; even if the table is full of food, it’s only an acceptable spread if there is lamb. For festive events, the guests of honor are served sheeptail. This is considered a sign of respect and the bigger the tail, the more respect you give the guest.

Traditional Greek dishes include: sourpá, khashlama (both dishes are variants of a thick soup or stew with meat), and kubite (a Greek meat pie). These and other dishes are common and found in other national cuisines like the Crimean Tatars, Armenians, and Georgians. Culinary borrowing is evidence that Greeks in Ukraine lived alongside all these other ethnicities for centuries.

Additional Greek foods include souvlaki — meat grilled on small skewers. There’s also the dish “tzatzíki” which is a cold sauce made from Greek yogurt, fresh cucumbers, and garlic. Pryazovian Greeks also make a traditional cookie called the khurube, which originally came from the Crimean Tatars and Bashkirs who call it “chak-chak”. These cookies were probably appropriated when Greeks lived in Crimea.

Mykola’s mom is Crimean and has both Ukrainian and Russian heritage. His father is a pure blooded Greek from Katerynivka. So Mykola is half Greek and a quarter Ukrainian and Russian. But it’s obvious, given his occupation, what he most identifies with:

— Well, clearly I’m Greek. If I herd sheep, then probably I’ve got more Greek blood in me. It’s not just in my blood, it’s in my bones!

Federation

The Federation of the Greek Minorities of Ukraine brings together all 102 Greek associations and charities and supports Ukrainian Greeks both with financial and administrative services. The Federation is involved in many festivals and local celebrations.

Oleksandra Protsenko-Pitsatzí is co-founder and chairwoman of the Federation. In 1995, she decided to create the federation after seeing how Pryazovian Greeks were struggling to preserve their cultural traditions and unite as a single community of Ukrianian Greeks:

— We (the Federation) have taken the stance that Greece is our historical homeland, but the country that has raised us, in which we were educated, and is intertwined with our children’s future is Ukraine. Therefore, we don’t think there’s any reason to immigrate to Greece.

Since then, Oleksandra has actively engaged in initiatives to revive Greek Ukrainian culture and its languages, which had noticeably declined under Soviet oppression. Ukraine is a multiethnic country, Oleksandra says, and Greeks are a part of it. When Ukrainian Greeks travel to Greece and say that they are Ukrainian, people mostly respond that they haven’t heard of Ukraine, but that they know of Russia:

—In multiethnic Ukraine, Greeks have their own unique role to play. Just like how back at its height, Greece provided the world with many epistemological foundations: philosophy, medicine, mathematics, history, culture, and art. We need to show that we are a big and important part of Ukraine. That we are a wise part, and that we will be proactively involved in Ukraine’s development as an independent country.

Pryazovian Greek and Mainland Greek culture overlap with a few things. But for the most part Ukrainian Greek culture is separate, distinct and localized. The Greeks of Pryazovia have often throughout their history moved around so instead of attaching themselves to a specific place, they have focused on who they were and are.

They are Ukrainian Greeks.