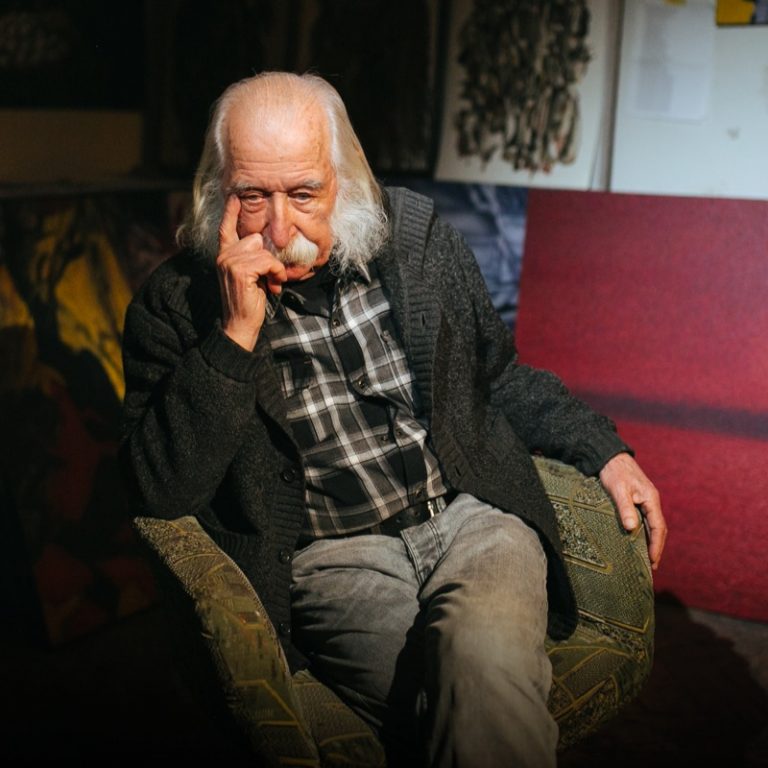

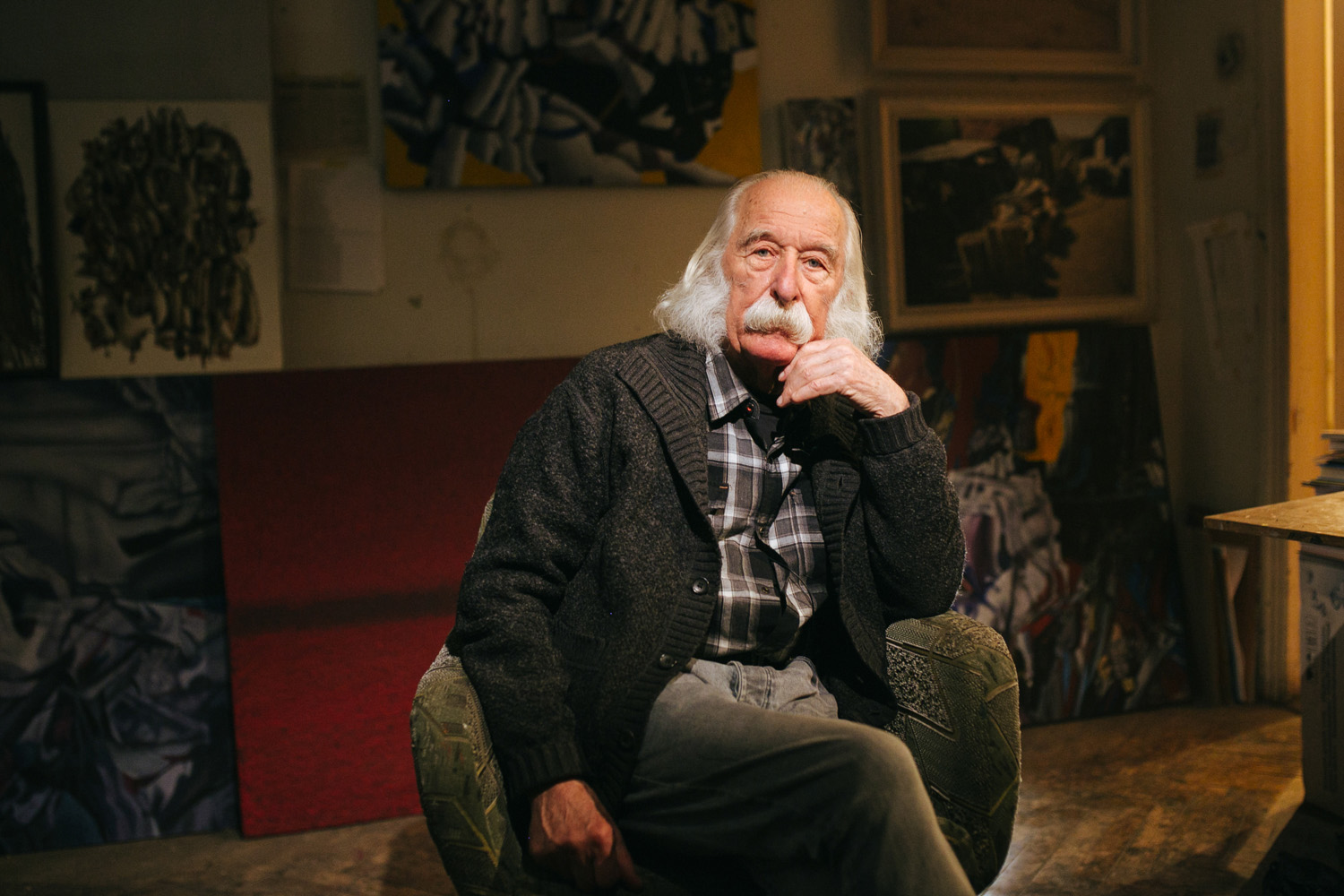

This is a story about one of Ukraine’s most famous contemporary artists — Ivan Marchuk, who has created thousands of works of art and invented his own technique — Pliontanism. Due to constant persecution from the KGB under the Soviet Union, Marchuk had to temporarily emigrate and returned to Ukraine in 2011. He is the only Ukrainian to make it on the Telegraph’s list of Top 100 living geniuses in 2007.

Ivan Marchuk is one of the brightest representatives of the group of Ukrainian artists who had the bravery to openly oppose social realism, the official art style of the Soviet Union forced onto artists by the government.

Marchuk’s development as an artist has been long and is still ongoing. From stretching himself as a young student as he attempted to find his own place within the Soviet system to wandering around the world to meet his incessant desire for learning, he has done all for the sake of perfecting his painting technique.

Ivan Marchuk was born in Moskalivka, Halychyna, in 1936 into a weaver’s family. With time, he crossed over not only the borders of his own village by becoming known worldwide, but also the limitations of most artistic styles and canons.

Marchuk began drawing already as a child and continued developing his talent as a teenager. He remembers when he fully realized that he wanted to become an artist.

“The first time I seriously considered myself as an artist was in seventh grade. Before that I played around like all children do. Though I had nothing to draw with: no pencils, no watercolor, nothing. There were flowers. To draw something in color you would use those flowers, the petals.”

While still in school, Marchuk decided that he wanted to study art professionally. At first he studied decorative painting at Ivan Trush Lviv Decorative and Fine Arts Vocational School, and later continued on to the ceramics department at Lviv State Institute of Applied and Decorative Art.

The Emergence of an Artist

Marchuk recalls how critical his time studying at the institute was for the development of his worldview. He joined the ranks of all art dissidents through his alternative and revolutionary approach to art thanks to progressive teachers who were knowledgeable about many artistic styles, knew current trends in art, understood the politics and history behind art, and were open minded thinkers who encouraged exploration far beyond the limits of social realism.

Social Realism

A method and style of Soviet art and literature that was popular in the 1930s and the only one officially allowed until the fall of the Soviet Union. Social Realism was the Soviet version of Monumentalism, the style characteristic of other totalitarian regimes.Marchuk joined an underground school started by his teacher, Karl Zvirynskyi, who introduced the youth to world cultural achievements and the hidden pages of Ukrainian history. Zvirynskyi’s school for young artists began in 1959 and continued their small gatherings for almost ten years. Besides painting, composition, and history, the school also taught world literature, music, and religion classes.

“At the institute, Karl Zvirynskyi was my art director and he critiqued my work a lot. He had a group of ‘his’ people, and we would all go to his house, a few guys, though later he told me he regretted spending all his life teaching and drew so little.”

Ivan Marchuk’s early work relied on naive art themes but after being introduced to avant-garde and modernism, he found the beginning of his own path in art.

“I was older than my colleagues, but at the time they were ahead of me in their approach to modern art, so I needed to transform into a modern ground-breaking artist. What a hurdle that was, a crazy hurdle that I needed to overcome and come out on a completely different side.”

After finishing his studies in the late 1960s, Marchuk moved from Lviv to Kyiv. He got a teaching job at the Institute for Superhard Materials and later worked at the Kyiv Combine of Monumental and Decorative Art which was dominated by soviet ideological artistic monotony and where western technologies were either filtered or not used at all. Marchuk completed all work orders quickly, so that he could have time to paint what truly interested him, what came from heart. At that time, he moved away from graphic drawings and seriously took up ink and tempera. As he states, he worked restlessly under the motto “I am who I am.”

Censured

That Ivan Marchuk worked on two fronts — officially and underground — was characteristic of most artists of that time. According to Ukrainian art historians, this dualism where artists seemingly existed in two dimensions was caused by the specific structure of Soviet artistic life. Everything that didn’t fall under social realism was considered ideologically harmful — meaning anything figurative and abstract, complex and moody, any search for a free form.

Since Marchuk’s work challenged the conventions of social realism, the Soviet government sought to ruin his artistic career by ignoring or suppressing his work and even directing the KGB to directly persecute and threaten him. This treatment lasted for years, reaching its peak in the 1970s, and caused Marchuk’s art to be under an unofficial ban for over 17 years.

“I was left out for 17 or 18 years. By 1975 I dreamed of escaping that hell. It was hell. The fact that I came from Lviv, you know, made me a nationalist. And the scariest part was that I interfered with the holy of holies — social realism, and began destroying it… in all of my art.”

Marchuk resorted to drawing trivial illustrations for Soviet magazines, such as Ukraine, Motherland, and Kyiv, just to survive. However, this simple job provided a fairly good salary — a drawing that would take Marchuk about 10 minutes was priced at thirty karbovanets, while a plane ticket from Ternopil to Lviv cost fifteen.

Marchuk’s artistic unfulfillment under Soviet totalitarianism and his experience of being constantly persecuted by the KGB made him want to escape from the USSR as far as possible. Marchuk left the Soviet Union in the late 1980s. Since then the artist has resided in Australia, Canada, and the USA. He finally returned to Ukraine in 2011.

Unlike many artists who emigrated from the USSR and had to accept any available job, Marchuk not only kept painting but received recognition while living abroad. Multiple exhibitions expressed the respect the artist never received in his homeland, just like most artists of that time. Marchuk was able to achieve something incredible during his exile — success and public recognition, to prove that some Ivan from Moskalivka could reach the top.

“My name became known all over the world. I dreamt of that.”

slideshow

Pliontanism

Every life event, even small ones, greatly influenced the artist that Marchuk is today. The constant change of residence significantly impacted how his creative methods formed. For example, after returning from the USA the artist began using thicker paste-like American paints because they last and dry longer. However, the paintings that used Soviet paints have preserved even now the detailed texture, due to a special technique that literally brings landscapes to life. These landscapes are described as hyper-realistic, even though he does not like his work to be bounded within the confines of defined styles.

“When I paint I use various ‘modern’ styles, whether it’s for instance this last limitless and sub-abstract surreal look, but just going out in quiet Ukrainian nature I see wonders in every little corner. Just like they say: people look but an artist sees.”

Marchuk’s creative origins can truly never be found in any single traditional art movement. His method is syncretic and this is what makes his work so valuable. The artist notes that he is able to and loves working intuitively and subconsciously. In his first series, Voice of My Soul, Marchuk as a still-young artist experimented with this method, and the result is something that art critics can neither define as impressionism or expressionism.

The artist confesses that he wages war with every piece and some canvases are never conquered. Even after finishing a painting, a whole new battle begins when deciding on a name for the piece. Marchuk remembers that in his youth he would play around with words and write poetry, but painting has always been much easier than giving a name to what he has created on canvas.

Ivan Marchuk uses his own unique technique called pliontanism. It consists of thin intertwined lines that merge into unbelievably detailed, outlined images. Marchuk creates with an almost child-like curiosity about the world and his paintings are hyper-detailed and tactile. Often, there is an illusion of an additional light source, especially in his nightscapes that focus on the Moon. This approach, which is somewhat similar to Arkhip Kuindzhi’s style, became another distinctive characteristic of Marchuk’s.

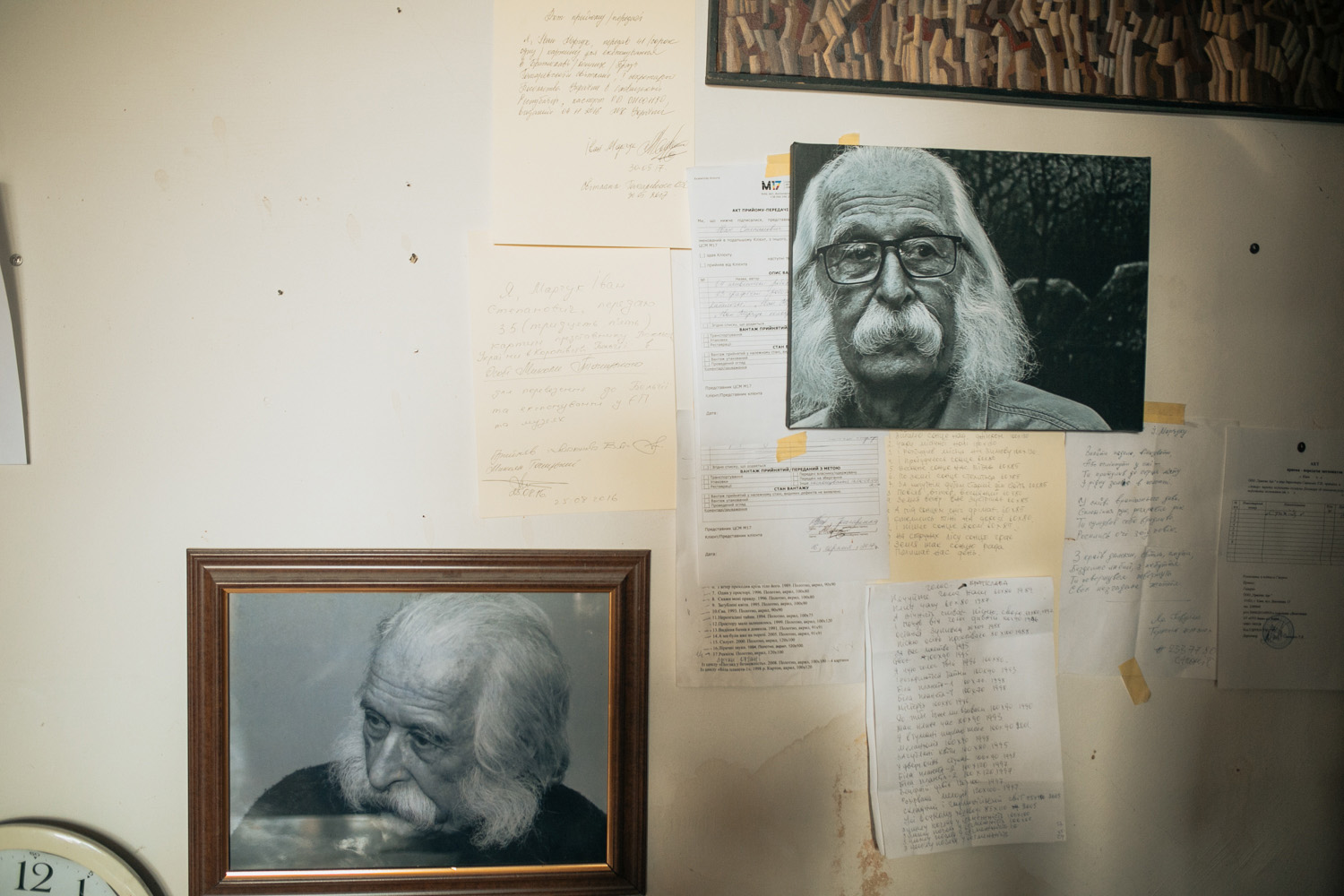

The artist has created over four thousand pieces, half of which are scattered around the world, given as gifts or artistic business cards (during Soviet times, he would create paintings small enough to hide and smuggle out of the country). And even though the rest of his paintings barely fit in Marchuk’s cozy studio, he currently only dreams of painting with large canvases.

slideshow

A philosophy of home

Marchuk has lived all around the world but considers himself tied to Ukraine, more specifically to the land and less so to the country. According to the artist, this love of the land is the reason for his hyper-realism in every depicted clump of soil, in the precise anatomy of a tree or in any other element of a landscape. Marchuk’s special perception of his native land and tangible memory of the earth where he was born eventually urged Marchuk to return to Ukraine.

“There, where our house was when my family lived there — that was home. My village was my whole world. With time my horizons broadened, and this whole land became my motherland. Not the country, but the land.”

In his respectable age, the artist continues to dream and create and still follows the latest news in the art world. He admires the work of his contemporaries, such as Liubomyr Medvid, the late Oleh Minko, Borys Plaksiy, and Mykhailo Dmytrenko.

Ivan Marchuk believes that Ukraine depicted in his paintings is full of wonder. Marchuk’s numerous international exhibitions testify of public interest in Ukraine and in the artist in particular. Marchuk is well known even beyond the USA. Over the past few years, his works have been displayed in many countries, such as Lithuania, Germany, Poland, Belgium, Hungary, Czech Republic, Slovakia, Turkey, Luxembourg, Thailand, and Tunisia.

“Everyone wants a new menu — to see something that he or she has not seen before. Well, I gave humankind an opportunity to see, to admire. Thailand has not seen snow, and neither has Turkey. I brought so much snow to my exhibits in Jordan for people to enjoy.”

The artistic message

Perhaps the most important element of any creative act is understanding what you are doing, and what you are bringing into this world. In this sense, Ivan Marchuk’s art is remarkably filled with meanings and archetypes. Moreover, Marchuk fully understands his role as an artist:

“To be an artist is to be human. A person exists to leave a footprint in history. If you are a truly gifted artist, you contribute a lot. Because, as they say, life is short but art is eternal.”

An ascetic lifestyle and an assiduous and diligent work ethic generally characterize artists, but Marchuk made these into a philosophical maxim. Marchuk is confident that he could survive anything, a life far away from his homeland, with no friends, not even language, as long as he is holding a paintbrush.

“I used to want to be like Skovoroda when I studied. I used to say, ‘I will go around with a walking stick, like Skovoroda did, and teach people all around the world, instructing them to do good’. Thank God, I was deterred; I gave it up. Later I thought, ‘Aha, maybe I’ll go to Leningrad and study to become an art critic’, but thank God, this also fell through. Some kind of fate was guiding me. Because, as I say, is it me guiding my fate or my fate guiding me. But I think that it guides me.”

Marchuk confesses that lately he has been working less and less. Though despite his age, he is still fairly active — he walks a lot, plays chess, and loves to swim in the Dnipro. Until recently, Ivan experimented with different physical and spiritual practices, for example he practiced yoga and meditation, and kept to a strict sleeping schedule and healthy diet.

Hryhorii Skovoroda

A famous Ukrainian philosopher and writer from the 18th century, who led a nomadic lifestyle.slideshow

Marchuk says that he always enjoyed experimenting and has a rebellious, non-conformist temper. The artist knows that even if he likes the idea of being in a relationship or having a home with pet cats, he will never be someone who can settle down and have a family because he is “a vagrant who cannot stick to a home”, he lives as a free artist.

“I have been an extremely rebellious person since I was a child. Above all else, I love freedom and liberty.”

Marchuk expresses his love for animals by taking care of homeless cats and tame ravens that live nearby.

It is my biggest delight to feed the ravens in the morning, I receive so much positive energy. But then when I go to buy a newspaper, I only ever get negative energy. Then I go to the easel and try to release all of that from my mind. You know, when you concentrate really hard, the negative energy escapes on its own. Because all my focus gets concentrated and you get pulled in, and from this a new painting begins to appear.

Marchuk’s studio became his own little world from which he barely ever leaves. Marchuk does not much enjoy painting en plein air since his landscapes with their specific weather conditions are mostly painted from memory; or perhaps it’s more accurate to say painted from his consciousness, since every natural phenomena he has witnessed is engraved in his very being.

“I have no paintings in my home, not a single one, because that’s where I rest, but the studio, that is a special place. Whoever comes to visit says, ‘The aura, what a wonderful aura!’ I rarely eat at home, usually I even have breakfast here. I’ve had this studio since 1982.”

This is how Ivan Marchuk creates his own world, his own alternate reality, that he eagerly shares with the viewer:

“I am, as they say, ‘a constant wanderer chained to an easel’, that’s who I am. All my life was like that. I could not ever rest, honestly, just couldn’t. As long as I have eyes, hands, a body, you see, they draw. This is my habit, my routine. And that is why I have done so much. I have not lived, I haven’t lived yet, I have worked.”