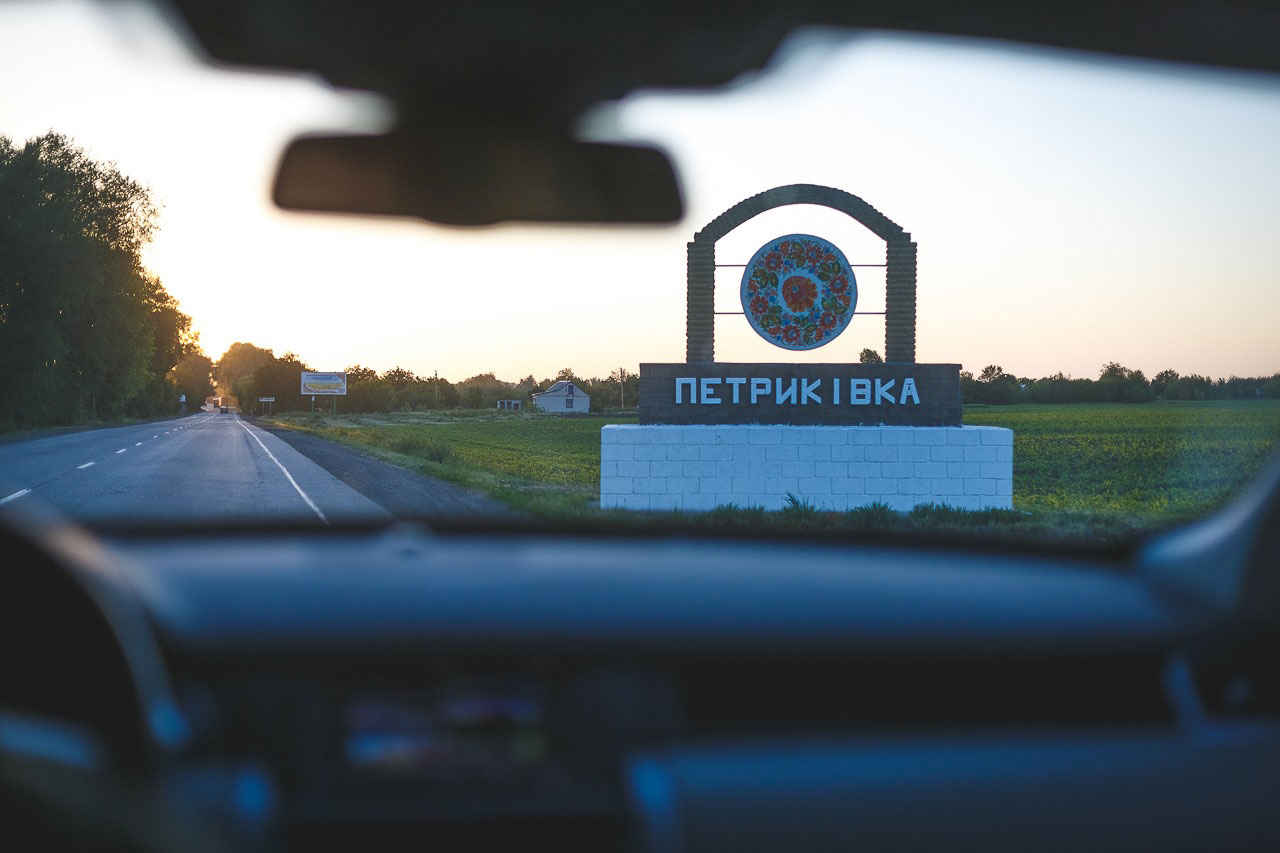

The village of Petrykivka is known for the eponymous traditional painting style — Petrykivka painting (or simply “Petrykivka”). Historically, people used it to decorate house walls, musical instruments and household items. Nowadays, these painting elements can be seen on a variety of things, and “Petrykivka” itself has become one of the characteristic and famous symbols of Ukraine in the world. In 2013, Petrykivka painting was included in the UNESCO Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity. Dozens of artists keep on creating unique patterns by using special paintbrush-making technology called “Kotyachka” (“Cat”).

Its cultural and artistic background can be felt all over Petrykivka. The village has not only managed to keep its artistic tradition, but continues to develop it even now. It remains a center of national culture up to this day. Here you will find the Centre of Folk Art “Petrykivka”, which draws people from all around the world wanting learn the artistic painting and talk to traditional artisans.

Each Petrykivka painting master follows their own individual path. Some had artists in their families, while others found it as a vocation. Andrii Pikush, Petrykivka painting master and the head of the Centre of Folk Art “Petrykivka”, belongs to the former. He shares familial ties with the artist Tetiana Paty, who has been teaching an entire generation of Petrykivka painting masters:

—My grandmother on my father’s side was a cousin to Tetiana Yakymivna Paty. This was my kindergarten due to the shortage of kindergartens at the time. On the way to her sister’s house, she would pull my hand to follow her. Ever since I was two years old, I have watched this painting process. Of course it struck me with its energy, like a current. I would always see new works in her house, get excited by them and dreamt of painting my own.

Nataliia Rybak also got to know Petrykivka art back in her childhood. She saw a painted jewellery box once. The box was made in the “Druzhba” Petrykivka painting factory, which, back in the Soviet times, mass-produced souvenir products:

—It was an absolute delight! It was a “Druzhba” jewellery box, and I was just like — wow! It was so exhilarating, dear God, a fairytale! Unbelievable. I was dying to paint as a child, but it hadn’t worked out. Fortunately, my school had industrial training, so that’s when I started to paint.

Master Halyna Nazarenko is indebted to her mother for revealing her talent:

—It’s my mother’s achievement, because she dreamt about painting. She never had the opportunity to do it, because of poverty that followed the war. We couldn’t afford to draw. She managed to achieve her dream through me. And then, when I wanted to go studying, she was always supportive of me. She is 80 now, and she still supports me. If my husband gets angry sometimes and says “you’re leaving again”, she will still tell me to “go — you need it.

Tradition

Traditionally houses — internal and external walls, especially the space around windows and doors — were decorated with Petrykivka painting. Similarly to vyshyvanka, these decorations were considered to protect from misfortune. Later ornaments migrated to household items — jewellery boxes and other furniture, musical instruments. When peasants gained access to paper, Petrykivka masters (who were predominantly women) started to paint on white canvas, which you could then fasten to a white wall.

Petrykivka consists of several basic elements, which give this decorative painting its distinct look. For example, all flowers are fantastic and have no analogues in real nature. In some way, tsybulka (a Ukrainian word for onion) came to symbolise the painting style. This element earned its name for its resemblance to an onion bulb cut in half. There is even a monument to tsybulka in the centre of Petrykivka. Another floral element is kucheriavka, which has a sort of twisted tuft. Petushynnia represents another special element of the Petrykivka painting. It consists of multiple thin lines and gives a painting certain transparency and weightlessness.

Not only floral, but animal and anthropomorphic elements feature in Petrykivka — although nothing is off limits for the artists. Nataliia Rybak says that “birds, fish and horses” are often-used elements in Petrykivka. Human figures appeared later.

—No one depicts people these days. And if they do, it’s more about, you know, elegant women. A real girl has to be wide. The earth should hum when she walks. She can take care of the garden, and she can milk the cow. Who cares about a moody Barbie on a diet?

slideshow

Not only the patterns, but the tools used to create Petrykivka, are extremely important in terms of preserving this artistic tradition. The most basic and accessible one is finger painting. Flowers, cranberry bush berries — you can create all of these just by dipping a finger in the paint and leaving a print on the paper. The tool that gives artists the most pride is a cat fur brush or “kotyachka”. Halyna Nazarenko explains that cat fur is especially elastic and with this brush you may paint both the normal and the very thin lines for petushynnia:

— We tried making brushes from wolf and hare fur, squirrel bristle. None of it was right. Kotyacka, however — now that’s what you need

slideshow

As it happens, there are many theories about which kind of cat fur makes the best brushes (although everyone agrees that only female cat fur should be used). Nataliia Rybak emphasizes that it is very important to hold serious diplomatic negotiations with the kitty, to get her to agree and not to scratch, and only then you can cut a little fur. Preference is given to simple stray cats. The best fur for a brush comes from under the paw and from the neck. Then the ends put together — a cut end to another cut end, and a sharp end to another sharp end — and attached to a stick with a simple string. The brush is now done! The older a brush is, the more “worked in” it is, and thus more valuable.

Artists point out the connection between petrykivka painting and the human aspiration to understand the world around us. Andrii Pikush believes that petrykivka holds a deep and yet unexplored meaning:

— Long before the rise of science, thousands of years ago, people understood the fundamental laws of life and cosmic evolution, the laws that govern all of the living things. In writing and art both, folk art embodied those symbols. This relates to things like embroidery, pottery, carving and petrykivka painting. I think that, when the time comes, and our children and grandchildren are defending their PhD and doctoral theses, they will uncover this meaning, this extremely deep cosmic meaning of the artform.

Nataliia Rybak draws the same parallel between human harmony and nature in life and art:

— A human being is not at the center of it all — nature is. Regardless, people put themselves first and think they can do whatever they want. No, that’s not right.

History

According to some local stories, the village of Petrykivka was founded in the seventeenth century by a cossack, Petryk, as a cossack winter dwelling. Another version tells that Petro Kalnyshevsky himself, the last Koshovyi Otaman of the Zaporozhian Sich, was its founder.

Nataliia Rybak tells:

— The Cossacks would winter here, and, because of this, the population had grown rapidly. They had to build a new church, because the old one couldn’t fit everyone in. The large village grew so fast that it started to swallow its neighbors. There were a lot of artists here. A great many crafts. Unfortunately, we’ve lost weaving entirely. We used to weave. There aren’t any masters anymore. Weaving with cattails. There’s the Chaplynka river — full of cattails, and not a single weaver. Only the petrykivka painting left now, and a little bit of vytynanky. Vytynanky used to be quite strong too.

In 1936, the folk artist and teacher, Oleksandr Statyva, founded a school of decorative painting in Petrykivka, where eager students were able to learn petrykivka painting at a professional level. In 1950, a new decorative painting factory opened on the grounds of the artel “Vilna Selianka” (Free peasant woman). It later developed into the “Druzhba” factory. All its souvenir products, embellished with the petrykivka painting, were being exported to nearly 40 countries around the world. The artists resented the working conditions and the idea of folk art industrialisation however, as Andrii Pikush explains:

— I objected to the conditions, when petrykivka was driven onto a conveyor belt.

Just then, we started to use black color in the painting, which went against that style’s traditional palette. Rumour goes that this was an intentional injection of Russian folk traditions into our art, namely khokhloma and zhostovo. Andrii Pikush conducted his own research into the origin of black color in petrykivka painting. In his mind, the human factor played a significant role here: petrykivka artists borrowed certain elements from similar Russian traditions and started to make use of them in their own works.

However, the Soviet policy of unification and the attempts to break up Ukrainian cultural traditions failed to destroy petrykivka. Halyna Nazarenko is pleased that her famous village managed to keep the original artistic path:

— The Soviet period saw all paintings destroyed. Each region used to have its own kind of ornamentation. We simply got lucky — we managed to preserve ours. At every stage, someone would step in to safeguard it.

Modernity

Like any artform, petrykivka painting does not standing still. It develops and reacts to the events and demands of the present. Hardly anyone still decorates their house walls with colorful flowers (though we do get such requests now and then!). Petrykivka is gradually taking on a new dimension. Halyna Nazarenko believes that petrykivka painting has every chance to become a fully-fledged gallery artform and attain global recognition:

— Petrykivka mustn’t stay in the past. It has to grow and move forward.

Halyna travelled just about the entire world with her personal exhibitions. Just in 2018 she had four exhibitions abroad. The fifth took place at the Ukrainian Institute of America in New York, though without her participation. She sees it as an act of cultural diplomacy, when people associate Ukraine with Ukrainian folk art instead of political events only.

— It’s all about image. You know, people abroad are not interested in the war in Ukraine, sadly. It hurts us, not them. Regardless, we have to cultivate a good image of Ukraine beyond our borders. And petrykivka — that’s something you could show both from an aesthetically pleasing angle and a positive one. That’s what I’m about.

After meeting a volunteer friend, Halyna came up with an idea for a new project, “Mamai of Bullet Casings”. It will be based on one of her pictures — the figure of a Cossack from folklore, formed from bullet casings delivered by volunteers and soldiers from the frontlines:

— When I had my American friends who collect petrykivka visit me, the volunteer Yurii Fomenko came with them. He keeps a blog about Mamais. And so we got to know each other, even though he himself is from Dnipro. Later on, he went to war again, and so he says: “Halia, send your Mamai”. Just then, I returned with an exhibition from France, and I had a small Mamai. Yurii came back from war and brought this Mamai for me to sign and said: “You sent it and didn’t sign. As long as it was hanging at 43rd brigade, we had no casualties”.

Andrii Pikush says that the artists at the Centre of Folk Art “Petrykivka” prepared an exhibition of over 200 works, which opened in more than 50 countries as part of this project. However, it isn’t only abroad that people are discovering petrykivka. Art at home is acquiring new meanings too.

slideshow

Petrykivka painting combines history, tradition and modernity. Artists agree that, while petrykivka remains a symbol of Ukrainian folk art, it also has tremendous potential for innovation. A contemporary reinterpretation of petrykivka is taking place right in front of us: t-shirt, sweatshirt, bag prints are all becoming popular. Petrykivka ornaments embellish cars, mobile phones; they are being used in a design, on dishes and household items.

Petrykivka painting artists grasp the changes and the challenges of today, carrying on the tradition and popularising it through their own art. Each one of them sees clearly their role and duty to develop this artform. To preserve it at home, in Ukraine. Since to find beauty, you don’t have to travel far away, says Nataliia Rybak:

—In 1993, I had a very interesting experience: I spent half a year in Canada and realized some things. Even if Ukraine is not that perfect sometimes, still I want to live there. I can’t express how much I love my land, the people here, my job. We have to change ourselves, break down our habits, adjust ourselves to that country. Why, if have so much beauty already? Why should I exchange it? We have fascinating customs and great people.

To the question of what petrykivka painting means to them, they answer unanimously: “it’s my life”. Nataliia Rybak explains:

— It’s my life and an integral part of me. If I haven’t been drawing for a long time, I simply get sick. It’s just impossible. An artist’s job is very interesting and resembles a career in sports: if you train, you will break records. If you don’t, you won’t achieve anything.

Folk art is something that unites, inspires and motivates. Nataliia Rybak considers petrykivka as an art worth spreading around:

— People are in need of that harmony. I think people do need this work, absolutely. Our people love this beauty, aspires to it; it is something they want to see and paint themselves. So there’s a lot of work left for me still, I think. We have to get the whole of Ukraine involved in our painting!

— So far petrykivka painting keeps living, fighting, but we’re only scratching the surface. Because, what do you think petrykivka painting is? Birds and flowers? Just imagine: fish, birds, horses, a folk artwork. It’s such a broad, universal phenomenon. It’s not all flowers, as everybody seems to believe. The world-famous petrykivka is, actually, world-obscure, because no one looks below the surface. It’s in your hands now — find it. There is very little of the real petrykivka left.

— During long winters, when I sit at home and work, it’s a kind of vitamin that gives me inspiration and good mood. I love and want to travel, and I’ve got big plans still, but I don’t mind. If you could compare my work (my life, really) to jazz, it would be pure improvisation.