The Ostroh Academy is one of the first successful examples of educational revival in Ukraine that doesn’t try to replicate the old Soviet system and leans on the long-standing traditions of Ukrainian education instead. The university in Ostroh has been in existence since 1576, but fell into decay after the death of the duke and his sons in 1636. When Ukraine gained independence, work began on renewing and moving Ostroh. During Soviet times, Ostroh was known for its mental hospital — a marker of Soviet rule, since such institutions would often host dissident academics and intellectuals.

The city of Ostroh in the Volyn region was a prominent landmark, well-known even during the ducal period. The buildings here carry remembrances of those times: monumental structures of the Lutsk Gate and the Ostrozky Castle have been converted into museums, and the ruins of the Ostroh Tatar Tower peek over a residential area. The city received a new lease of life after 1994 with the arrival of prospective students of the Ostroh Academy. By that time, the population of Ostroh numbered fewer than 10,000 inhabitants. At first, the idea of restoring the educational institution seemed farfetched to all but Ihor Pasichnyk. Nowadays the Ostroh Academy is a famous feature of the city, known for its unusual approach to education both in Ukraine and abroad.

Ostroh

The modern-day university in Ostroh could be considered as one of the newest universities in Ukraine. At the same time, founded in the 16th century, its historical counterpart became the first higher educational institution in Eastern Europe. Back then it was called the Ostroh Slavic, Greek and Latin Academy. The city’s cultural and educational growth revolved around the reign of Kostiantyn Vasyl Ostrozky. The Duke Ostrozky relocated the ducal residence from Dubno to Ostroh, and, in 1576, founded an educational institution and began building the university. In the prior year, the duke established a printing house in Ostroh and invited the best printer of his time, Ivan Fedorovych. Meanwhile, he was surrounding himself with a community of the best scholars, theologians, publicists and icon painters, and would give them access to the best library of dictionaries, grammar, Greek and European theological literature, reprints of ancient works, etc. This set a precedent unlike any before: the union of Byzantine and Western European cultures. It was made possible by borrowing a system of education from Western Europe which taught the seven basic sciences — grammar, rhetoric, dialectics, arithmetic, geometry, music and astronomy. It also stemmed from the very first opportunity of learning higher sciences in the land — philosophy, theology and medicine — as well as mastering five languages, being Slavic, Polish, Hebrew, Greek and Latin.

Ostroh

according to some, the city should be called “Ostrih” in Ukrainian

Kostiantyn Vasyl Ostrozky won 86 battles as a military commander, predominantly against the Tatars. Each of these battles prevented the Tatars from entering into Central Europe. It is difficult to overestimate the historical significance such victories have had on the preservation of Western culture.

The Duke Ostrozky, called by some the uncrowned king of Rus, baron of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and senator of Rzeczpospolita Polska, having the right to seal with red wax (a right reserved for kings and barons of special merit), created something in Ostroh that would come to be seen as Ukrainian renaissance.

He continued to expand the reach of Eastern Orthodox theology but turned to Catholic theological works for enlightenment, creating the conditions for community improvement. As for the Ostroh School, which later became the university, he made it his priority to establish the resource base needed for the first scientific and educational institution, so the income from nearby villages would go towards it automatically. One of the first significant contributions to the institution was made by duke’s niece, Halshka, who donated a large sum of money in her testament: “— for the hospital and the Ostroh Academy, for the Holy Transfiguration Monastery near Lutsk over the Styr river and for the village of Dorohynia: 6,000 in Lithuanian currency”.

Thanks to such powerful backing, Ostroh was gaining momentum. In 1578, the first “Greek-Russian Church Slavonic Reader” in Ukraine was published here. Later on, an alphabet book, the New Testament and, for the first time in print, an accompanying alphabetised index were published here as well. The overall number of Ukrainian first prints that came out in Ostroh is astounding. The Ostroh Bible remains the chief success and achievement of that period. Printed in 1581, it became the first comprehensive Orthodox canonical edition of all 76 books comprising the Old Testament and the New Testament in Church Slavonic.

A well in the bedroom

The educational institution premises from the ducal period have not been preserved. Regardless, the modern-day university is situated in a building with a very interesting story. The monastery is its oldest building. It was constructed in a baroque style. All of the baroque ornamentation was removed shortly after to make everything simple and functional. Duke Janusz Sanguszko gifted this territory to Capuchin monks, and, in 1778, a church was sanctified here. It was then that basements and dungeons, which could have been linked to the general system of Ostroh catacombs, were strengthened. The monks were using them as living quarters and, according to tradition, as crypts to entomb their brethren.

slideshow

A well was constructed right in the middle of the monks’ kitchen, deep enough to allow constant access to clean water. The monks would prepare medicine and hand out free lunches. After the November Uprising (also known as the Polish–Russian War 1830–31), Russian authorities forced them to leave the monastery. There is evidence to suggest that they were given only one hour for packing. It was too little time to pick up all of the important things, such as medicines and books.

In the 19th century, the building was being used as a girls’ college for future teachers and governesses. Antonina Bludova founded this institution and named it after her father, Earl Dmytro Bludov. The college operated on these grounds between 1865 and 1922. When the college opened, Ostroh was front of mind thanks to works written about the Ostroh Bible. A decision was made to set up a women’s Orthodox college for girls aged 9 to 16, and so the Church of the Holy Trinity became the Cyril and Methodius Church.

slideshow

Later, this site would host a Polish teachers’ training college, and even saw the Capuchin monks return for some time. After the war, it was a warehouse, a variety of educational institutions, and during the 1970s and the 1980s, a boarding school for children with latent forms of tuberculosis. The room with the well, now boarded shut and forgotten, was said to be cursed due to permanent humidity, coldness and “terrible sounds coming from under the floor”.

It was only in the 1990s when the room was handed over to the university, that the floors were changed. The worker removing the old floors watched his hammer fall through the wood and heard it hit the ground sometime later. This is how the well was rediscovered, and, after a while, restored to its original state. The room now hosts one of the exhibition halls of the Museum of Ostroh Academy.

New academy

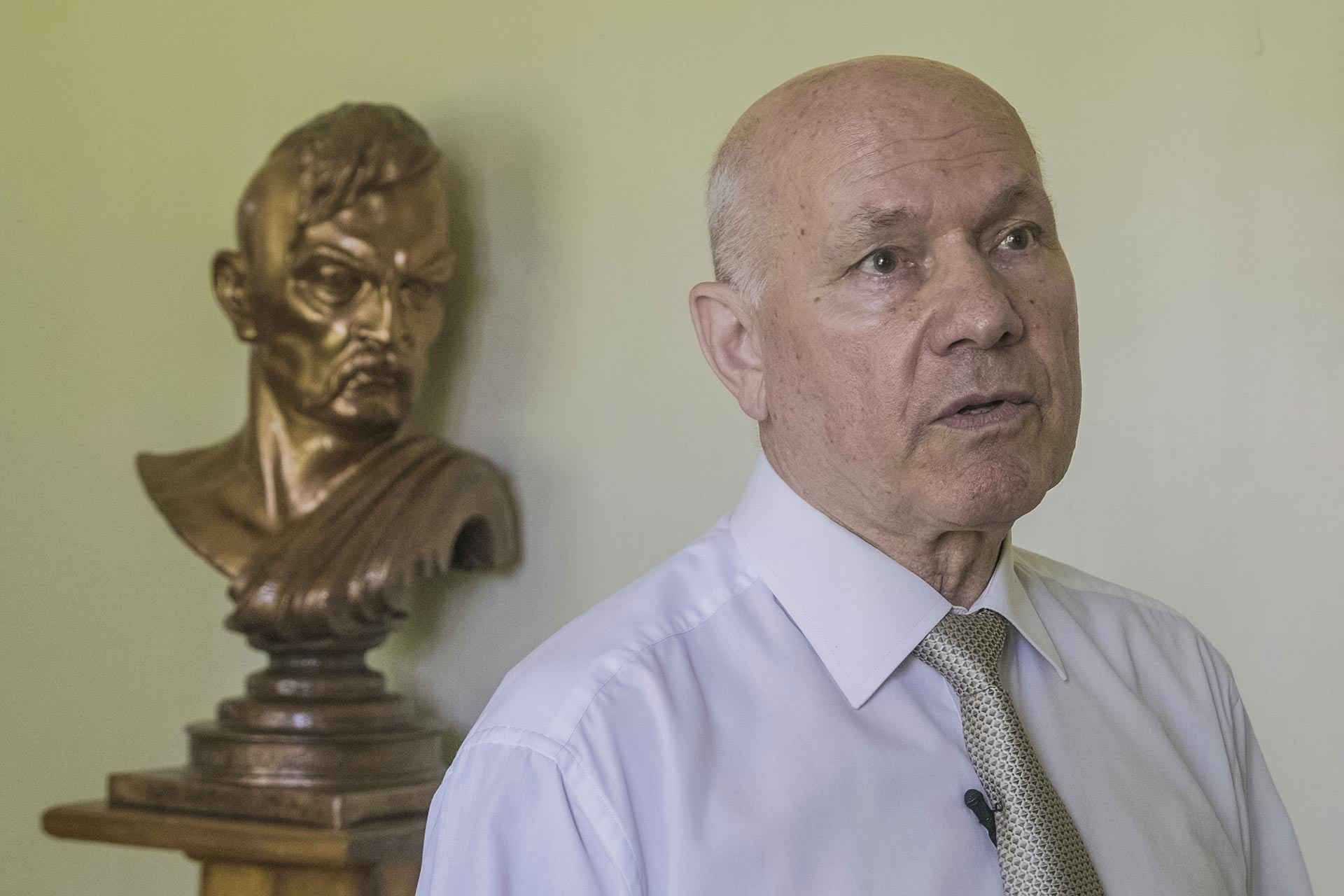

Ihor Pasichnyk, the current rector of the Ostroh Academy, can talk about the university’s revival for a long time and in great detail, given he lived through each stage of the university’s foundation:

— When I arrived, this was a ruin in the full sense of the word. There was nothing here: no tables, no chairs, no books, no rooms, let alone professors.

At the time, in the early 1990s, he was the only PhD in Western Ukraine, and he had planned to move to a bigger city. However, a meeting with Prime Minister Mykola Zhulynskyi and the head of Kyiv-Mohyla Academy, Viacheslav Briukhovetskyi, changed his plans and prospects.

They told him about Ostroh and the history of the academy, about the dukes and the publishing house. Ihor had no idea about any of it at the time — the Soviet Union had erased all accounts of the Ostrogski family and the Ostroh Academy, and Ostroh was known solely as a district center with a large psychiatric hospital:

— It was the most outlandish idea you could come up with: to restore the Ostroh Academy in some godforsaken town, in spite of its past status as a capital city. I was about to run away from here, naturally. What my friends thought of Ostroh, well, there’s a mental hospital here, you know, a big one. So they joke that I would end up there soon enough anyway because agreeing to go to Ostroh and for nothing was a ridiculous idea at the time.

Meanwhile, the Ostroh Academy possessed a huge legacy, which still benefits the university’s development to this day. As the rector points out:

— The history hangs over us. We can’t afford to do worse than our ancestors.

Ihor Pasichnyk had decided to come up with a concept for the university, a first of its kind in Ukraine. In the interviews he gave, he spoke about the past glories of Ostroh and its university, which would soon come to attract students from all over Ukraine, including Kyiv:

— Every time I left the TV studio with a feeling of disbelief in my own words. Kyiv, seriously? Last year alone we’ve had 15 gold medalists (pupils granted with the highest award for excelling at their studies) from the leading lyceums and high schools of Kyiv. So everything that I spoke of turned out to be true.

It was made possible with the help of philanthropists and people invested in our success. Their names are stamped on a special plate that overhangs the science library entrance. A lot of them are people from the diaspora and entrepreneurs. They donated a massive amount of money because they believed that the level of Ukrainian education would improve one day. At first, there wasn’t a single book here. Today, we have a library of half a million, one of the best online libraries and a collection of invaluable early printed books:

— Someone rich would offer a two-bedroom apartment on Khreshchatyk (one of the central streets in Kyiv) for a single early printed book. You know how much an apartment on Khreshchatyk costs. Just for “Apostol”, for example, since it is the only original copy of the first book published in Ukraine. And even being poor, one person brought it and granted to Ostroh Academy

In 1993, the first discussions about ways to restore the Ostroh Academy took place at the ministerial level. It gained significant support: from the rector of Kyiv-Mohyla Academy and the regional council heads to various officials and advisers to the President. As a result, in December 1994, first 100 students began their studies at the university. In another two years, Leonid Kuchma (the President of Ukraine at the time) signed a decree to rename the Ostroh Collegium into a university. In 2000, the university gained national status.

The university’s departments continue to grow, new faculties and specialties appear all the time, sustainable development gains a foothold and the amount of students, which has reached five thousand at this point, is on the increase.

At this stage, the university has an important opportunity to organize exchanges and form associations with several leading European universities.

Today, Ihor Pasichnyk sees the restoration period as a worthwhile challenge, despite having had to start from nothing:

— We had a brigade come from Lviv. These were the heads of an architectural institute. They gave us their conclusion: we’re better off taking a bulldozer and leveling it to the ground. In their opinion, there was nothing here that could be restored, neither in theory nor in practice. Nobody could think of another way forward. We didn’t even have a roof here. There were 140 cracks in our church, there was mould, and no one could imagine that this was possible.

He believed that you could build a higher education institution in a tiny town, one that would appear on the list of the best universities not only in Ukraine but internationally as well:

— And here, all of a sudden, the Ostroh Academy returns, like a phoenix rising from the ashes.

The Ostroh Academy differs from other universities significantly. The head of the university has dreams that extend far beyond the boundaries of these walls:

— I’m interested in the formation of Ukrainian thinkers, in the youths that don’t flee abroad. And if they do flee, at the very least, they should work according to their specialties.

The academy graduates have occupied senior positions both in Ukraine and abroad for over ten years now:

— The chief auditor of Luxembourg graduated from the Ostroh Academy. According to the Forbes magazine, our Sasha Talavera — an Ostroh Academy graduate — is among the top five best known and distinguished economists of the world. Yes, he works in London, but he works for Ukraine.

Ihor Pasichnyk explains that chasing foreign students is not the purpose however:

— I dream that at least 70% of my graduates don’t move and remain to work in Ukraine instead, build the country they want.

The Academy’s professors go beyond sharing their knowledge and work to shape a generation of Ukrainian thinkers. They believe that what Ukraine needs the most right now are leaders that will bring the society together. It’s important to begin with a moral component. A student who has never given a bribe won’t take one tomorrow. They will form around them a community of conscionable people instead.

— The Ostroh Academy had accomplished this goal once before when it first began in the 16th century. I think that our university will accomplish this goal too. We find ourselves in a similar position, and Ukraine needs us to succeed.

For Ihor Pasichnyk, it matters shape not only the educational process, but the students’ personalities too. He stresses that a lot of people come to study in Kyiv because of stereotypes. They believe that Kyiv means better job opportunities:

— Studying in Kyiv doesn’t necessarily give you a better education.

Open society. Open education

The National University of Ostroh Academy is the only educational institution in Ukraine that has proven by example the viability of a university in a district centre. It was created in line with the American approach, where the smaller cities have more space for the students and professors to engage in scientific and creative activities. As for the rector, he sees it as a positive. He considers cities such as Kyiv to be oversaturated. On the other hand, building a university in the district centre can bring with it a breath of fresh air and a new take on its historical background:

— Take Ostroh for example. This town was absolutely degraded. There was nothing here. The university gave it a strong new lease on life.

People in the university are convinced that an open society starts with open lecture rooms. The doors to the lecture rooms have modern glass inserts, so that everyone knows what is going on in the lecture.

Some lecture rooms are not only thematic, but filled with a certain artistic sense. Some of the rooms have pictures of fine art, others have antique vyshyvankas on display. In certain rooms, the lectures are being held with a live accompaniment on the piano (introduction to classical music taken over a trimester is an obligatory class for all students). The rector emphasizes:

— People don’t have the opportunity to learn this. Not at the school, not at the kindergarten, not at the university. They don’t understand, you know, what the classics are. But the classics must underpin all moral values and attitudes.

Students often take his words with a degree of doubt. His daughter is an opera singer and a pianist after all, so his enthusiasm is entirely understandable. At the same time, the students themselves will advise others not to miss “the week of Yurii Plyska”, when, instead of mundane studies, you can spend time enjoying auditory pleasures and laughing at the Warsaw University professor’s witty jokes.

The example with artists and composers serves to show that the university prioritizes its students’ personal development while staying within the boundaries of an educational program. The institution treats the issue of bribery with utmost determination. Its employees strongly believe that, when a student is taught not to give or take any bribes, that student will gather like-minded people around them in their future workplace.

Speaking of the ways to create such an environment at the university, Ihor Pasichnyk states the following:

— It’s pretty simple: don’t accept bribes yourself. You know, a simple method of fighting corruption and bribery is to have the people in leadership reject it. This will then put them in a position to prevent others from taking bribes. I believe this wholeheartedly.

He believes strongly that the university is educating prospective leaders and thinkers, who will be able to make Ukraine stronger from the regional level. But the Ukraine that we all dream about cannot be built on bribery.

Nevertheless, everyday and holiday in an Ostroh Academy student’s life are framed in certain canonicity and tradition. The academic choir Gaudeamus performs at every inauguration and convocation, as well as other auspicious occasions. You can attend a church service, which can be heard all over the central courtyard of the university, before the daily lectures. Instead of the standard “Miss University” there is an annual “Halshka”, so named in honor of one of the university’s first founders. It is likely this kind of approach that helped the university get into the Book of Ukrainian Records eight times, and even to be immortalized in the Guinness World Records for “the longest poetical marathon”. The latter was achieved by a 456-hour non-stop reading of Kobzar by Taras Shevchenko organized in March 2014.

Ihor Pasichnyk himself emphasizes that teamwork made all of this possible. During the 1990s, he was recruiting young people who were not afraid to work towards the creation of a new educational institution, one that would measure up against the world standards. He tells that the selection criteria were very strict: mandatory knowledge of English, a desire to take an internship abroad by assignment, a certain level of physical fitness, methodology and knowledge and — a cause of derision among the rectors of other universities back then — young age:

— They joked that I recruited children, and what kind of a university is that, what a joke. They’re envious now because these youths defended their theses, they got their PhDs, became doctors of science. And most importantly, they are experts in the international arena, in new educational technologies, each one of them teaches their own course.

Nowadays such a team is the object of envy for other universities since many of Ukraine’s scientists are of retirement age. On the other hand, the average age for deans and vice-rectors in Ostroh is quite young:

— It’s all young people. My own age is skewing the statistics, but the average age is 34 years, the age of Jesus Christ, the age to create!

In 1994, when the first workers were recruited to the university, their eyes shone at the mere mention of the word “independence”. Everyone wanted to serve the country, not to flee it. This feeling made an impression then, and it is shared by the team to this day:

—We built our foundations on traditions: we’re a team, a team that works together extremely well. I feel so sorry for them because they have such small salaries. Yet they work so selflessly, that I can’t help but feel proud of them.

The well-coordinated team created something the rector calls a miracle of the Ostroh Academy restoration, the preservation and advancement of national educational heritage. As for Ihor Pasichnyk, his efforts earned him the title of Hero of Ukraine back in 2009: I’m not a hero of Ukraine, and I didn’t bring the Ostroh Academy back to life. It’s my colleagues. They are remarkable people. And, I think, our students are no less remarkable. I know that 10% of them will end up like anyone else, but the other 90% will raise the bar and raise it high.

— I’m not a hero of Ukraine, and I didn’t bring the Ostroh Academy back to life. It’s my colleagues. They are remarkable people. And, I think, our students are no less remarkable. I know that 10% of them will end up like anyone else, but the other 90% will raise the bar and raise it high.