Our next episode of Ukraine Through the Eyes of Others features Andreas Umland, a political scientist specializing in contemporary Russian and Ukrainian history, regime transitions, and a wide range of topics in post-Soviet studies. His extensive body of work spans diverse subjects, including research on the post-Soviet extreme right, European fascism, East European geopolitics, Russian nationalism, and others. Mr. Umland holds the position of Senior Expert at the Ukrainian Institute for the Future in Kyiv and serves as a dedicated research fellow at the Swedish Institute for International Affairs in Stockholm. Based in Kyiv, he also works as an Associate Professor of Politics at the esteemed National University of Kyiv-Mohyla Academy.

In this interview, Mr. Umland offers valuable insights into multiple facets of Europe’s geopolitical dynamics and international relations. He delves into the influence of Alexandr Dugin on shaping Russia’s present policy towards Ukraine and sheds light on the historical context that has contributed to the speed of Germany’s delivery of military assistance to Ukraine.

Andreas, can you tell us about how you got interested in studying this region? When was the moment when this interest was born?

Well, as you’re asking about how the interest was born… I was born in East Germany to a Russian mother. And like many other ‘Ukrainianists’, I came to study Ukraine by first studying Russia. So I lived in Russia for a while, and I studied Russian ultra-nationalism and wrote dissertations on such people as Vladimir Zhyrinovsky and Alexander Dugin. Later, I ended up on a position here, in Kyiv, at the Shevchenko University, as a visiting lecturer. I fell in love with Kyiv, with Ukraine. That was in 2002, I learned Ukrainian and then also specialized more and more in Ukraine. I also stopped visiting Russia because the situation there became worse and worse. I’m still studying Russia, especially the far-right, but also the leadership of Russia. But now, mainly, I focus on Ukraine and the war.

You wrote a dissertation called “Post-Soviet ‘Uncivil Society’ and the Rise of Aleksandr Dugin: A Case Study of the Extraparliamentary Radical Right in Contemporary Russia.” In there, you explore the concept of the far-right and the figure of Dugin. Could you expand more on that work of yours?

I came to the study of Russia through the study of modern Germany. Inter-war Germany, especially in fascist Germany, but also in late 19th century Germany, was the first rise of antisemitic parties. Then towards the end of the 19th century, the antisemitic parties actually disappeared. And it could seem that if the antisemitic parties disappeared, the antisemitism would have disappeared too, but that did not happen, as we know it from later history. The antisemitism became so widespread and so much part of the general German culture already that these antisemitic parties lost their point. And my point in the dissertation was that there was something similar in the 1990s in Russia, where we had the rise of Zhyrinovsky and other far-right parties. Also, the Communist Party of Russia became de-facto a far-right party, and its ideologies didn’t disappear. But on the contrary, they were picked up by people like Vladimir Putin, and now there’s not that much difference any more between Dugin and Putin. I would still say there is a principal difference, and one of them is a revolutionary imperialist, while the other is a conservative imperialist, but they’re both very aggressive. I wrote this in the early 2000s when these developments took place. I wrote my first dissertation on Zhyrynovsky, and then Zhyrynovsky became less important, and then it seemed that people like Dugin became more important. But Dugin was not a party politician, and he never demonstrated the relevance of his ideas by electoral support. He never became a political figure. Nevertheless, I think he had an impact on post-Soviet Russian development and, of course, a very negative one. He was actually the first one who formulated the current ideology of the Russian policy towards Ukraine. What Russia is now doing to Ukraine was already written by Dugin in his book “Основы геополитики” (Foundations of Geopolitics) in 1997, almost 30 years ago.

And how would you describe his formulations of this policy towards Ukraine?

He wanted the whole Black Sea Coast, right to Transnistria. And obviously, Russia wanted to do that, too. They wanted to take Odesa and so on, but they couldn’t. But what has now happened actually was prescribed by Putin. He said: “You know, Ukraine has no right to exist; we need the Black Sea area; this country is not a real country.” These are the things that we are now hearing from Putin, Medvedev, Patrushev, and so on. Dugin was more radical, and he was a revolutionary — he wanted to create a new Russia, a new world, that is not something that Putin wants. He wanted rather a restoration of the old empire. So, there’s a difference between them. But the Ukraine policy was something that Dugin basically formulated. He was not the only one, there was another called Evgeniy Morozov in the 1990s, who also wrote about “Novorossia.” There were actually many of them — you have many of these civil or uncivil society actors, and Dugin was just a case study. Maybe, he was not even the most important one of all of these actors, but this uncivil society basically prepared the Putin regime and Putin’s foreign policy.

You talk about the culture of Russia and also about the fact that there is not only a top-down approach but also a bottom-up in terms of this idea of a new Russia. And then we have an argument of “This is just Putin’s war. This is just Putin and his ‘members club’ that want this, but if somebody else comes, we will have peace.” What do you say about that specifically?

The problem is much deeper. In a very strange sense, I encountered Ukraine first as an object of Russian imperialism in the 1990s when I was not yet here. I studied Zhyrinovsky and Dugin and other far-right extremists, and they were already obsessed with Ukraine. So, you have the sort of popular non-acceptance of Ukraine as a state, which is widely spread in the population, but which was not violent and anti-Ukrainian, or genocidal eliminationist-Ukrainian. And then you have the ideologists like Dugin and others.

For instance, the annexation of Crimea was immensely popular in Russia. And this popularity of the annexation of Crimea became the pretext for the new annexations because that was good for the regime, so there was also a certain rationality here to do that. And that has a lot to do with the wider non-acceptance of the Russian population of the Ukrainian State. I was just discussing this with a colleague, Anton Shekhovtsov, that since the start of the big invasion, we have yet to see the attempt of a general strike in Russia. So, one can understand that people don’t want to go on the street and risk being arrested and so on. But why was there no attempt to simply do a strike and stay at home for two weeks or so? And it’s actually supported by the opinion polls by the Levada Center. People don’t say what they think in these polls, but why was there no then general strike to prevent the war? Yeah, the problem is much larger than Putin, obviously. But for the functioning of the regime, Putin is really important. I still have a lot of hope for the moment that Putin disappears because what I think then will happen is that it will be very difficult for the clans to determine the successor of Putin. They need a method of determining the successor, and Putin has now also lost legitimacy and authority. Putin cannot easily determine a successor because he’s a loser now. So, if he says: “You know, this is going to be my successor,” it may not be that the others will accept him. It will then create domestic instability and also lead to political changes that will eventually be beneficial to Ukraine.

Well, I think Putin is definitely a loser for the world, but is he a loser inside Russia? Because it’s very easy for him to create the impression that he’s not. And a lot of people buy into that idea. But is there something that tells you that in Russia, he’s also might be considered a loser?

Yeah, maybe a loser is too strong a word, but he has certainly lost a lot of authority since the 24th of February 2022. Before that, he had the annexation of Crimea, a more or less successful sort of foreign policy on his own terms. He was seen as an important and major player. And now, the Russian army is weak, Putin is weak, and the Russian people have become unpopular. You see in the worldwide polls that Russia’s simply much less popular than it used to be. The Russian economy will start to suffer from the sanctions more and more, the living standards will go down, and the economy will not develop. So, at the end of the day, he will come out from all of this as a loser.

And then there is also this perception of Navalny as “the only hope for the future of Russia.” Many people still praise him and see him as this big, great figure that will come and suddenly bring democracy and freedom and stop the war. And there are also Ukrainians who are sceptical of this figure because of his xenophobic expressions and far-right views. What’s your opinion on Navalny and on the criticism as well as the praise that he receives in the West specifically?

I cannot look into his head at the end of the day. I don’t know how he would behave once he gets power, if that ever happens. I still would be rather hopeful because the statements he has recently made and the development that I’ve seen in his surroundings seem to indicate that he has changed from his earlier nationalist times. The recent statement that he made the declaration, basically, was okay – “Crimea is Ukrainian, we should get out of Ukraine” – and all of that. So, I still think of him as a rather hopeful figure if he ever gets out of prison and if he gets power. I understand that Ukrainians are sceptical. But if he ever gets out of prison and becomes president or prime minister, then this will be a very different Russia, also a very different Ukraine. That would be a positive development. It’s simply one of the figures that we have. For instance, I know Vladimir Kara-Murza personally very well, he is an intellectual, and I greatly like him. And he never had these sorts of ambivalent episodes in his biography as Navalny and others. But he isn’t a major political figure, not in Russia, whereas Navalny is. So, you know, here I would be rather pragmatic and see him as the best hope, perhaps, still for Ukraine.

How do you think it’s possible to get the restorative justice that we demand as Ukrainians from a figure like Navalny, who’s still very hesitant about it?

So many things would have to happen before that becomes then actually a topic and an urgent assailant question. I’ve talked to one of his close associates, Vladimir Milov. And from the way he talks about this, they acknowledge that there have to be reparations, there has to be this restorative justice, and guilty people have to be put in prison and have to go to court. And we know that from German history, there’s the question of responsibility. After World War II, people were saying: “Well, I didn’t know,” “We couldn’t do anything,” “It was a dictatorship,” and so on. If there were another, more popular Russian politician with fewer problematic episodes in their past, then I would prefer that person. But I don’t see anybody comparable to him. But this is all very theoretical so far.

Would the Russian people ever be able to see Ukraine and then the rest of the region and the world without their imperialist bias, and do you believe they will ever be able to accept the responsibility for the crimes?

The German experience shows that it is possible. But the German crimes are higher than the Russian crimes so far.

What do you mean by that?

There were 50 million dead, gas chambers, and so on. So, what is now happening in Ukraine is terrible, but still, the Holocaust is something specific. But we are not at the end of the story, it can be here even worse. Some people say that what would have to happen is actually that the current Russian state would have to disappear in its current form for the imperial impulse to disappear. And it’s actually what happened to Germany that the old German state disappeared, it was divided, and then later reunified. So, maybe something like that would have to happen to Russia, too. Maybe Ukrainian decentralization will help to transfer power in a reconstituted Russia to the local level. And then, perhaps, politics and political thinking would change. That may be an alternative to the breakup of the country because then people would be more engaged with the local affairs of their village or of their city.

Let’s move to your academic background. What is the perception of Ukraine in Academia? And do you think that Academia, in general, is changing and decolonizing its views on other parts of Eastern Europe?

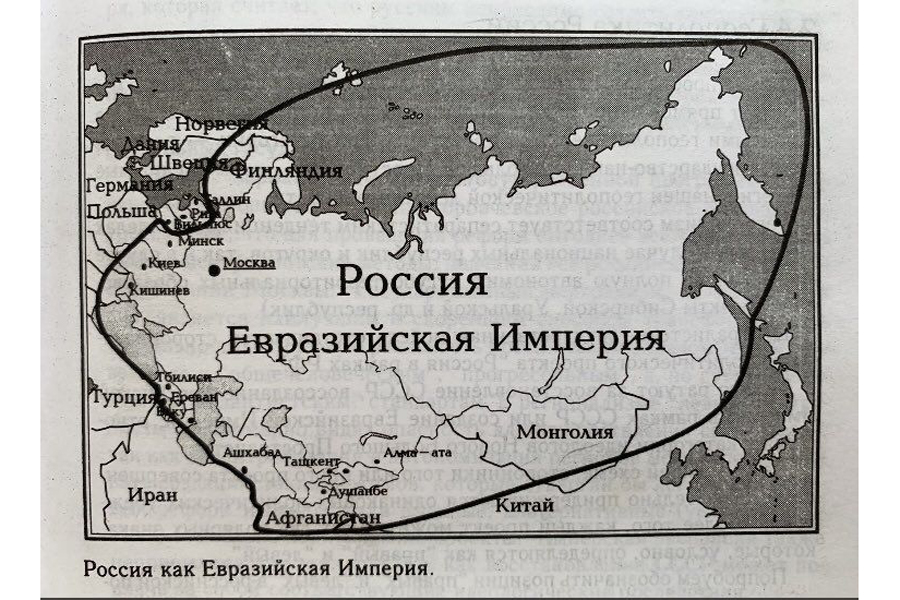

I have been to the major centers in Edmonton and Harvard, in England, and so on. But I don’t know as well the history of Ukrainian studies as other experts whom you may have interviewed here. The problem here is that when the term “Eurasian” is used, what is meant is not the Euro-Asian mega continent — the whole of Europe and the whole of Asia — but something else. And it’s also not Central Asia. But what is Eurasia, actually? When you use it for this post-Soviet sphere, then it’s actually a proto-fascist term. This is because it comes from Eurasianism, which is the idea that there is some sort of special civilization between Europe and Asia. Eurasianists were very different from the current so-called ‘neo-eurasianism of Dugin’. So, actually, there isn’t that much connection between Dugin’s neo-eurasianism and classical Eurasianism of the 1920s and 1930s. But the way they used Eurasia, it was actually a proto-fascist term. It was the idea that there’s a civilization, sort of unknown civilization, between Europe and Asia, with the center in Moscow, and it has to be sort of reborn, rediscovered. A colleague of mine, Leonid Luks, had already written about this 30 years ago. He argued that there’s a lot of similarity between these Eurasianists who shape the term ‘Eurasian’ and ‘Eurasia’ and ‘Eurasianism’ of the 1920s-1930s and in the diaspora, the Russian diaspora. It was not in Soviet Russia, and the German conservative revolution — these intellectuals who basically prepared the rise of Hitler. They were not part of the Nazi movement, but they also had this sort of idea of a special German path and so on. Generally, Germany was held to be partly responsible for the decline of the first German democracy, and the Eurasianists were structurally very similar to the German conservative revolution. Therefore, the use of the term ‘Eurasian studies’ is very dubious. Now, finally, it’s changing: East European studies and post-Soviet studies are changing very deeply, and I think there’s now a lot of critical self-reflection about this. This is one of the reasons why the West reacted so late and so little to all of this, that it did not react sufficiently in 2014 and in 2008 when Russia invaded Georgia. But it is reacting now. This process has started, and as I see from social media, there is some sort of conference or project that wants to reform the Western study of Eastern Europe.

I want to return to your work in Stockholm, Sweden. Sweden is holding the presidency of the Council of the EU currently. What’s your impression of their presidency overall? And what are the main issues that the Council of EU is dealing with right now about Ukraine?

I’m not Swedish, so I’m not so deep in it, and I also don’t read Swedish. It’s a Germanic language, but it’s not actually very similar to German. So I’m not deep in this Swedish discourse, and a Swedish person would perhaps also talk about this differently. But Ukraine is really a major topic for the Swedish presidency and Swedish politics, not just for foreign policy. It’s extremely present. The sympathy for Ukraine in Sweden is exceptionally high. It’s actually higher than in my home country, in Germany, where you have these sorts of ambivalent discourses, especially in East Germany. That has already been proven earlier by, for instance, the Eastern Partnership program that Poland and Sweden together initiated. And it’s also shown by the disproportionate amount of help that Sweden is providing. Sweden is a small country, it’s not as large as Germany, but it’s providing a lot of help in various way, including military aid.

Do you think that support of Sweden and other Northern countries is shaped by history or their own relations with Russia in any way?

I must admit that I am not well-versed in the detailed history of Sweden and other Northern nations. What strikes me, as a German observer, is that, at an abstract level, the general outlook on the world in both Germany and Sweden is not vastly different. However, when it comes to practical foreign policy decisions, especially in the lead-up to the full-scale invasion last year, we saw Sweden and Germany taking divergent paths. Sweden emerged as a more substantial supporter of Ukraine, despite not being a NATO member. It held a more pragmatic view of Russia and, considering its size, displayed remarkable support for Ukraine. In contrast, Germany seemed to have a certain fascination with Russia, although this sentiment has been waning recently.

In fact, my optimism has been growing, particularly over the last six months, concerning Germany’s stance. There is a notable shift in the political landscape, with new publications critiquing previous policies. This change is encouraging. In Sweden, on the other hand, such a transformation may not be as necessary, given its historically robust foreign policy. I’m afraid I cannot provide a detailed analysis of Sweden’s position due to my limited knowledge of the country.

And since you mentioned Germany, and you’re German, can you comment on their position towards Ukraine and how it’s changed?

The German approach to Ukraine has a somewhat complex history, which can be seen as a downside of the so-called ‘Ostpolitik’ pursued over the last five decades. This policy has seen some peculiar developments, notably during the 1980s when a special relationship was cultivated between the East German Communist Party, the Socialist Unity Party, and the Social Democratic Party. There were long lines of special relations between Russians and Germans, as the two numerically largest nations of Europe. This entailed long-standing ties between Russians and Germans, the two most populous nations in Europe. It involved a sense of shared cultural interests and a deepening economic engagement, including energy ties.

This history is intertwined with a broader theme of German pacifism, which emerged in the aftermath of World War II. While pacifism had its merits at a certain point, it became increasingly unrealistic as Vladimir Putin rose to power. It was perhaps justifiable during Boris Yeltsin’s tenure, but it proved inadequate in assessing the evolving dynamics of Eastern Europe under Putin’s leadership.

The military assistance Germany is now providing to Ukraine should arguably have been extended two years ago. Such support might have altered the course of events, and we might’ve not had this war now. Regrettably, it was not a viable option at the time. In the summer of 2021, Robert Habeck, a German politician who currently serves as the Minister of Economics, suggested supplying weapons to Ukraine during his visit to the Donbas region. This proposal sparked a significant controversy and was considered unthinkable at the time. However, we are now witnessing a shift in Germany’s stance, with the delivery of weapons to Ukraine, including more potent arms. While it is better late than never, I find myself increasingly optimistic about the evolving narrative.

There is a growing body of literature criticizing past policies, and I hope that a parliamentary commission will eventually oversee a critical reflection on these matters.

What’s the cataclysm of that change? Because the moment of the invasion didn’t make it happen. Do you believe there are specific individuals or groups driving this transformation within Germany?

The official German response was remarkably prompt and resolute. Chancellor Scholz, in his address on the 27th of February, proclaimed, “We are now entering a different era. We must adapt.” On the official front, the reaction was swift, and I must admit, I was pleasantly surprised. However, the translation of this shift into practical policies lagged behind. Decisions regarding the provision of weapons were delayed, and the turning point in Germany’s perception may have been the influx of Ukrainian refugees.

As decisions were made, initially concerning anti-aircraft weaponry, followed by artillery and eventually tanks, there has been growing criticism, alongside a reevaluation of past positions. Yet, we still lack an official parliamentary commission tasked with conducting a comprehensive review of these matters. The issue at hand is that individuals associated with the previous policy are still in positions of authority. Our Federal President, Frank-Walter Steinmeier, who had close ties to former Chancellor Schröder and entered politics through that connection, remains in office. While he has acknowledged his mistakes, there is a pressing need for a more thorough and formal critical reflection on past missteps.

You mentioned your desire for Germany to take a more active role, particularly in a military capacity, in supporting Ukraine. How would you respond to those who are skeptical of this approach, and why do you believe Germany should enhance its support for Ukraine, particularly in military aspects?

The prevailing argument often revolves around our obligations within NATO, asserting the need for our own military contributions. However, what makes this argument peculiar is that two critical factors have shifted. First, it has become evident that NATO’s preparations were oriented towards countering a Russian military force that, as it turns out, did not exist in the manner we had previously assumed. The events of the past year have demonstrated that the Russian military is considerably less effective than many within NATO had believed. This is one intriguing aspect.

The other peculiar element is that despite these changes, NATO’s plans and structure remain rooted in countering a Russian military force that has, in part, ceased to exist. In essence, we find ourselves preparing to confront adversaries who have been effectively neutralized in Ukraine. The Baltic countries, for instance, are fully aware that the Russian tanks destroyed in Ukraine no longer pose a threat to them. This underscores a more rational approach to the situation. And you would think Germans are rational, but we are not often.

Germany’s significance will likely increase significantly once peace is established, and the full-scale reconstruction efforts commence. Germans possess the requisite experience, structures, institutions, and organizations to contribute effectively in such endeavours. While we no longer engage in military conflicts, there appears to be a disconnect or misperception between Ukraine and Germany. Some in Ukraine seem to regard Germany as a major military power, which we are not. While we do have a thriving military industry and excel technologically in certain military areas, we lack the necessary military force on a significant scale. This, in part, explains our limitations in providing the support I would personally hope for.

Last summer, you wrote an open letter to your international colleagues, where you called on international political science, international relations experts, and the community to visit wartime Ukraine. Why do you think that being in Kyiv, or in any other part of Ukraine, is something that is valuable for people of your background?

This article came out in several languages, and several points have also been criticized. People have said: “Well, this is wartime tourism, and there’s a certain voyeurism associated with that.” But the article’s point was that both traveling to Kyiv and Kyiv itself were safe. Now we have these frequent attacks, and I wrote this article last summer when it was actually rather quiet. You know much better than me, it’s more likely that in Kyiv, you will get hit by a car than by a missile. And so, the point was simply to say to my colleagues scientists: “You have history happening here, and you can come to observe it.”

And what’s your personal favorite place in Ukraine that you would recommend other people to visit?

My beloved city Odesa – the combination of a very convenient and very lively city with the sea, with beaches. I also really like water. And I also do ice bathing in the winter and here at the Dnipro river as well. But there you have everything — a nice city, excellent restaurants, beautiful architecture, and beaches, so what else do you need?