Evil unpunished only grows stronger. For many years, the international community failed to adequately address Russia’s aggression against Moldova, Chechnya, and Georgia (Sakartvelo), its occupation of Ukraine’s Crimean peninsula, and the Kremlin’s support for terrorist groups in the east of Ukraine and around the world. For decades, the grave breaches of international law by Russia were concealed under the guise of a “pacification” policy. However, the short-lived illusion of peace ultimately paved the way to the bloodiest conflict in Europe since World War II — the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine, resulting in hundreds of thousands of international crimes.

Investigating war crimes, gathering evidence and bringing perpetrators to justice are vital for achieving accountability during wartime. Therefore, it is essential to understand how international law defines these crimes and how the investigation process works. In collaboration with Kateryna Rashevska, a lawyer from the Regional Center for Human Rights (RCHR), we examine the different types of international crimes, the feasibility of holding Russians accountable, and the procedures involved in these efforts.

War has been a constant throughout human history, but it was only in 1945 that it was condemned as an ineffective method to resolve disputes. With the establishment of the United Nations (UN), its founders declared that war was no longer a legitimate means of settling conflicts and explicitly prohibited it. However, the restriction on the use of force in international relations is not absolute, as states retain the right to use armed forces for individual or collective self-defence. Aggressors often exploit this exception by manipulating and distorting concepts. For instance, in response to Ukraine’s complaint about violations of the Genocide Convention, Russia argued before the UN International Court of Justice that it was “preemptively” invoking Article 51 of the UN Charter to prevent an “alleged attack by the Kyiv regime” – a clear attempt to justify illegal actions under the guise of self-defence.

International crimes: a general overview

The earliest ideas of who qualifies as an international criminal can be traced back to Rome’s Cicero, who introduced the concept of hostes humani generis — “enemies of humanity”. He argued that certain acts violate the interest of every member of the international community, allowing any state to punish the perpetrators, regardless of where or against whom the crime was committed. In the 17th century, some states regarded pirates and slave traders as international criminals. Today, however, only the latter is recognised as an international crime.

In 1948, during the World War II Hostages Trial, the United States military tribunal defined an international crime as “a generally recognised wrongful act that concerns the international community as a whole and therefore falls beyond the exclusive jurisdiction of any single state under normal circumstances”. Since then, through the work of the UN International Law Commission, and the establishments of the International Criminal Tribunals for Yugoslavia (1993–2017) and Rwanda (1995–2017), as well as the International Criminal Court (ICC), it has been established that international crimes include war crimes, crimes against humanity, genocide, and aggression, also referred to as “core” international crimes. Other contenders for international crimes include terrorism, torture, and piracy. The recognition of what constitutes an international crime is determined exclusively by states through the adoption of international treaties.

The Hostages Trial

legal proceedings addressing Nazi war crimes, specifically focusing on the abduction and execution of civilians during the Balkan campaign. These trials were part of the broader effort to hold perpetrators accountable for atrocities committed against non-combatants during World War II.The definition of each specific international crime is outlined in the Rome Statute of the ICC and the accompanying Kampala Amendments. Genocide is defined as the act of killing or causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of a national, ethnic, racial, or religious group with the intent to destroy this group, in whole or in part. It also includes inflicting severe bodily or mental harm, creating conditions that lead to the group’s destruction, and forcibly transferring children from one group to another.

Photo: Getty Images.

Crimes against humanity are acts committed knowingly as part of a widespread or systematic attack directed against any civilian population. These include murder, extermination, enslavement, deportation or forced displacement, imprisonment or severe deprivation of physical liberty, torture, sexual and gender-based violence, persecution, enforced disappearance, apartheid, or other crimes of similar gravity.

Apartheid

the official policy of racial discrimination, segregation and oppression, implemented by the ruling elites of the Republic of South Africa against the local black population and Asian migrants from 1948 to 1991.Genocide and crimes against humanity can occur during both wartime and peacetime, while war crimes are specifically linked to armed conflict. These violations of international humanitarian law, which governs the conduct of war, are subject to individual criminal liability on both national and international levels. The Rome Statute lists 26 types of specific war crimes, including wilful killing, torture, taking hostages, and deliberately targeting civilians and civilian infrastructure. It is essential to distinguish war crimes from military offences, which specifically relate to military misconduct like misuse of property or revealing military secrets and are prosecuted under national laws.

Rome Statute

is an international treaty that established the International Criminal Court (ICC) in 1998 and came into force on 1 July, 2002. As of now, 137 countries, including Ukraine, have signed the Rome Statute, and 124 have ratified it.

Photo: Peter Dejong (AP).

Armed conflicts are directly related to the crime of aggression, which involves individuals in positions of control over political or military actions planning, preparing, initiating, or executing such crimes. This includes the use of armed force by a state against the sovereignty, territorial integrity, or political independence of another state. The full list of acts of aggression is outlined in UN General Assembly Resolution 3314, adopted in 1974.

What international crimes has Russia already committed in Ukraine?

An analysis of the illegal actions perpetrated by the Russian Federation from at least February to March 2014 reveals that these acts are not merely incidental “side effects” of armed conflict but reflect a deliberate, systematic strategy by the aggressor state. Before the full-scale invasion, the Office of the Prosecutor of the International Criminal Court (ICC) noted in its 2020 final report that the Russian agents’ actions in the occupied territories of Ukraine exhibited signs of war crimes and/or crimes against humanity. These actions, which often overlap and fall under various classifications, include deliberate killings, intentional attacks on civilians and civilian objects, torture, unlawful detention, enforced disappearance, forced mobilisation, denial of the right to a fair trial, sexual violence, deportation and forced displacement, and the seizure and destruction of property, including cultural heritage.

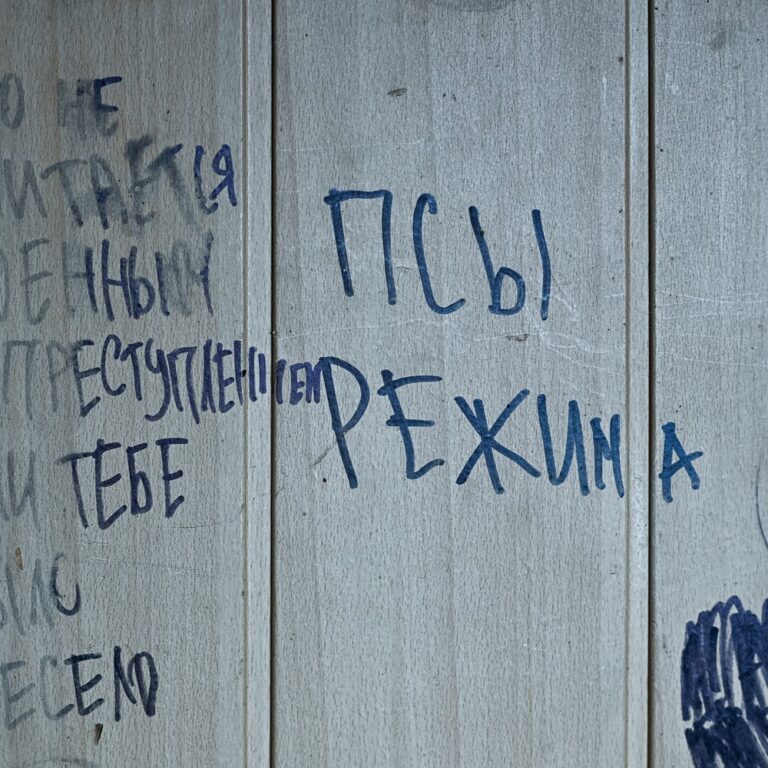

Photo: Viktoriia Yakymenko

Following the onset of the full-scale invasion on 24 February, 2022, investigations into international crimes committed in Ukraine expanded globally, involving not only the ICC but also the Joint Investigative Team, the UN Independent International Commission of Inquiry on Ukraine, and the Moscow mechanisms. Their investigations confirm that Russian troops in Ukraine are committing multiple international crimes, including the act of aggression that sparked the full-scale war.

Additionally, Russian military groups systematically violate the fundamental principles of warfare, including distinction (between civilians and combatants), proportionality (ensuring that military advantage outweighs harm), caution (ensuring that targets are military objects), and humanity (prohibition of methods that cause excessive suffering).

The UN Independent International Commission of Inquiry on Ukraine

a body established by the United Nations in March 2022 to investigate and report on human rights violations committed during Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine.In addition to the previously described war crimes committed by the Russians up to 2022, the cruel treatment of prisoners of war has also been added to the list.

Since the start of the full-scale war, the Russian occupation forces have been the primary perpetrators of large-scale and systematic human rights violations in Ukraine, some of which have been recognised as crimes against humanity. This includes intentional attacks on energy infrastructure, which affect civilian population.

Moscow mechanisms of the OSCE

a special group of experts dedicated to examining violations of international humanitarian law and international human rights law, and providing recommendations on how to address these violations.The “filtering” measures imposed by the Russian Federation on the occupied territories should also be regarded as crimes against humanity. These measures involve the registration, interrogation, and detention of Ukrainians attempting to leave Russian-controlled territories. Those who do not pass the “filtration” process face detention under harsh conditions, including torture, unsanitary environments, and severe shortages of food and water.

Another severe breach of humanitarian law imposed by Russia is the deliberate deportation of Ukrainians from occupied territories. The unprecedented scale and systematic nature of these displacements, including deportation of children, prompted the International Criminal Court to issue arrest warrants for Russian President Vladimir Putin, and Commissioner for Children’s Rights Maria Lvova-Belova on 17 March 2023.

Filtration

a violent, unregulated scrutiny conducted by Russian-established authorities in occupied territories to assess the loyalty of the population by examining their personal data, social contacts, and attitudes towards Russia.The Kremlin’s policy of relocating and Russifying Ukrainian children mirrors the Nazi practices of World War II, which aimed to kidnap and re-educate children from occupied territories to strengthen the aggressor state. This includes forcibly imposing Russian citizenship and the ideology of the “Russian world”. Additionally, children are coerced into joining so-called “military-patriotic movements”, such as the “Youth Army” and the “Movement of the First”, where they are groomed to serve in the Russian army and taught to regard Russia as their Motherland.

“Russian world”

a Russian state ideology promoting the unification of states neighbouring Russia based on their affiliation with the Russian language, culture, and shared history.

Photo from russian propaganda media

Characteristics of the genocide committed by Russians in Ukraine

According to Volodymyr Vasylenko, an international courts and tribunals judge, the distinct feature of Russia’s strategy in Ukraine is that the war crimes and crimes against humanity committed by its forces are integral components of a broader effort to commit genocide against the Ukrainian nation. In fact, a single act can be classified as multiple international crimes if it meets the necessary criteria. For instance, in the case of Jean-Paul Akayesu, the mayor of Taba in Rwanda, the tribunal affirmed that “The simultaneous accusation of committing several of these [international] crimes on the same set of facts is valid”. This phenomenon is known as cumulation.

Today, deportations and forced displacement of civilians, indiscriminate attacks on energy infrastructure, and sexual violence are among the crimes with the greatest potential for cumulation, potentially including genocide, in the context of the Russian war against Ukraine. According to International Criminal Court Prosecutor Karim Khan, these crimes are a priority for investigation by his office.

Photo: Yakiv Liashenko

Latvia, Lithuania, Estonia, Poland, Canada, the Czech Republic, and Ireland recognise the Russian actions in Ukraine as genocide. Historian Timothy Snyder shares this viewpoint:

“For me, it is a clear case [of genocide]. I think people in the West avoid saying ‘genocide’ because they know that it is. And If they said that it was, it’d require more action and it’d require them to ask themselves why they didn’t do something earlier on.”

Indeed, the obligation to prevent, stop and punish genocide falls on each state party to the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, which currently includes 153 states.

The Russian rhetoric of hatred further supports the view that their war crimes and crimes against humanity can amount to genocide against the Ukrainian nation. This hate speech can be seen as evidence of a specific intent to commit genocide, and as incitement to genocide, which is an international crime in its own right. Statements by high-ranking Russian officials denying Ukraine’s statehood, questioning its national identity, and accusing Ukrainians of Nazism to justify their actions reflect a clear policy to eradicate Ukrainian national identity as well as their promotion of the Russification in education and culture. Such genocidal rhetoric is being documented by the UN Independent International Commission of Inquiry on Ukraine.

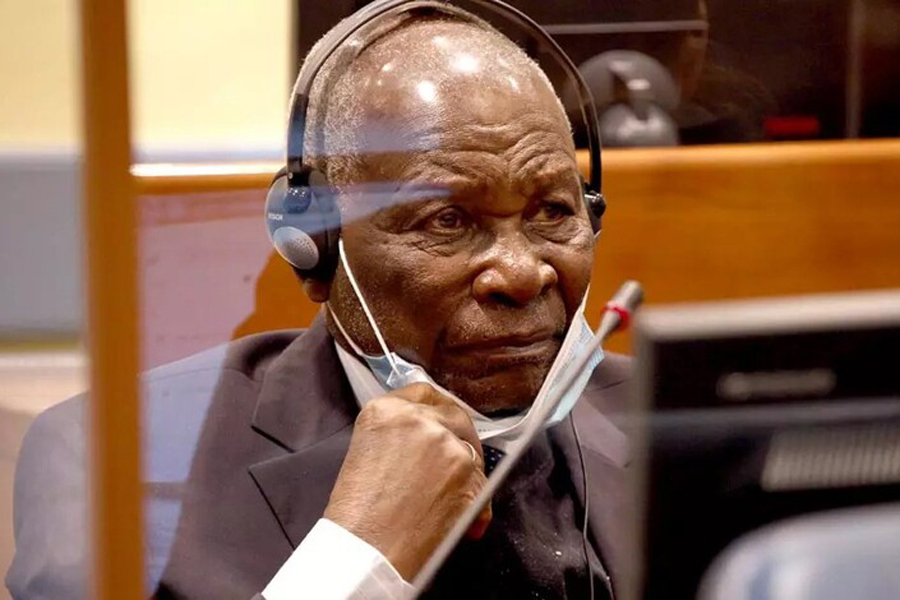

Historically, incitement to genocide has played a crucial role in the commission of the crime itself. Notable examples include the Holocaust, where Julius Streicher was prosecuted for his role in inciting genocide, and the Rwandan genocide, where the Radio Télévision Libre des Mille Collines was accused of inciting violence. In both cases, the instigators and propagandists were held accountable for their actions.

1994 genocide in Rwanda

mass murders of the Tutsi people, orchestrated by the Hutu majority, which resulted in over a million deaths and an estimated 150,000 to 250,000 rapes, according to UN estimates.

Photo: Leslie Hondebrink-Germer (UN-IRMCT)

How to hold Russia accountable and make it compensate for the damage?

The primary responsibility for prosecuting international criminals rests with Ukraine. However, due to the scale of the committed crimes, the high status and immunities of certain figures, such as Russia’s President Putin, Belarusian President Lukashenko, Russian Foreign Minister Lavrov, and the Chairman of the Russian Government Mishustin, the ICC and more than 20 states, including 14 EU members, have pledged support to Ukraine and established a Joint Investigation Team on 14 March, 2022.

Perpetrators of international crimes committed by Russians in Ukraine can be prosecuted in foreign courts under universal jurisdiction, which allows any state to pursue international crimes regardless of where they were committed. As of October 2023, the Joint Investigative Group’s investigations have led to 18 cases being opened in Eurojust, eight in EU member states, and two in non-EU countries, with Ukraine participating in the proceedings.

Eurojust

the European Union's agency for judicial cooperation in criminal cases, which facilitates cooperation between national judicial authorities within the bloc.Regarding the ICC, in 2014 and 2015, Ukraine recognised the Court’s jurisdiction over alleged crimes occurring on its territory under Article 12(3) of the Rome Statute. The Prosecutor’s Office investigated the situation in Ukraine for seven years before launching a full investigation on 2 March 2022, which resulted in the issuance of arrest warrants. The extended duration of the case at each stage — preliminary study, investigation, court hearings, and compensation for damages — can be attributed to several factors: the ongoing armed conflict, the severity of the crimes committed by Russia, and the absence of clear procedural timelines in the Court’s governing documents.

The main advantage of the ICC is its ability to prosecute senior officials of the Russian Federation, despite their privileges and immunities. However, the Court lacks jurisdiction over the crime of aggression because neither Ukraine nor Russia is a party to the Rome Statute (Ukraine ratified The Rome Statute in August 2024 – ed.). This gap could be addressed by creating a Special Tribunal for Aggression against Ukraine or by amending the Rome Statute. Implementing either option is challenging, as it requires the agreement of over a hundred states, the conclusion of relevant international treaties, the adaptation of the Ukrainian legal system, and the establishment of a functioning body for prosecuting perpetrators. Additionally, it is unlikely that Russia will recognise the ICC’s jurisdiction or become a member of the Court in the near future. This will continue to hinder the ICC’s ability to address the crime of aggression, even with Ukraine’s ratification of the Rome Statute.

Photo: Getty Images.

In addition to delivering verdicts, the mentioned courts and tribunals can also satisfy victims’ claims for fair compensation, which is as fundamental as the rights to justice and truth. Currently, efforts are underway to explore options for confiscating and repurposing frozen Russian assets.

For instance, on 12 October 2023, the Estonian government approved and sent to Parliament a resolution on using frozen Russian assets to compensate for the damage caused to Ukraine and its citizens. Similar legislative initiatives are also underway in Canada, the United States, the United Kingdom, and Latvia. Furthermore, an international compensation mechanism is gradually being established. On 17 May 2023, the Summit of Heads of State and Governments of the Council of Europe approved the establishment of the International Register of Damages Caused by Russia’s Aggression Against Ukraine, which was launched in April, 2024. Currently, certain categories of victims can submit compensation claims through the Ukrainian state portal Diia.

The International Register of Damages is one of the four components of the future compensation mechanism, alongside the Claims Commission, the Payment Fund, and the international treaty that will establish the framework for the first three elements. Thus, while compensation for the damage caused by the Russian Federation is becoming a reality, it is important to anticipate lengthy processes.