It is impossible to fully grasp the history of Ukraine, and even of Europe, without understanding the history of Crimea. This peninsula in southern Ukraine is a place where ancient myths were born, cities were founded, battles were fought, and empires clashed. Here, the European and Turkic worlds intersect, Christianity meets Islam, and cultures coexist. Crimea’s history is crucial for understanding the nature of Russian colonialism as Russia has employed numerous colonial tactics on this peninsula, distorting the truth to its advantage.

The indigenous population of Crimea has endured Russian terror for centuries, with the 2014 occupation marking a significant escalation in Russia’s systematic agenda. For the past decade, Russia has enforced a repressive, disinformation-driven policy aimed at shaping a specific narrative around Crimea. The Kremlin has militarised the region and used it as a launchpad for the full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022.

Despite its central role in Russian colonial narratives and practices, Crimea remains an underexplored issue. Both in Ukraine and internationally, there is a glaring shortage of unbiased information about its true history and identity, which are distinctly non-Russian. The status of Crimea continues to fuel debates, with some questioning “Shouldn’t the peninsula just be part of Russia after all?” It’s crucial to dismantle the persistent Russian myths surrounding the region, as the Russo-Ukrainian war — and any future Russian military aggression — cannot truly end as long as Crimea remains under Russian occupation.

Myth 1: Crimea has always belonged to Russia

Russian historical narratives view the 18th century as a pivotal time in Crimea’s history, beginning with its first occupation by the Russian army in 1771. In the Russian mindset, these lands were previously seen as devoid of significance. In reality, Crimea was home to a rich tapestry of diverse, multi-ethnic communities. At the time of this first Russian occupation, it was inhabited by peoples who had long established their presence on the peninsula and continue to reside there today: the Crimean Tatars, Krymchaks, and Karaites. These Turkic-speaking groups had dominated the present-day southern part of Ukraine since the 4th century AD. However, the earliest known inhabitants of Ukraine’s steppes, dating back to the 8th century BC, were the Iranian-speaking Cimmerians, Scythians, and later the Sarmatians and Alans. From the 7th century BC onwards, the peninsula became a focal point of Greek colonisation, resulting in the establishment of numerous ancient cities along its shores. Additionally, from the 11th century onwards, Crimea became a destination for significant Armenian migration.

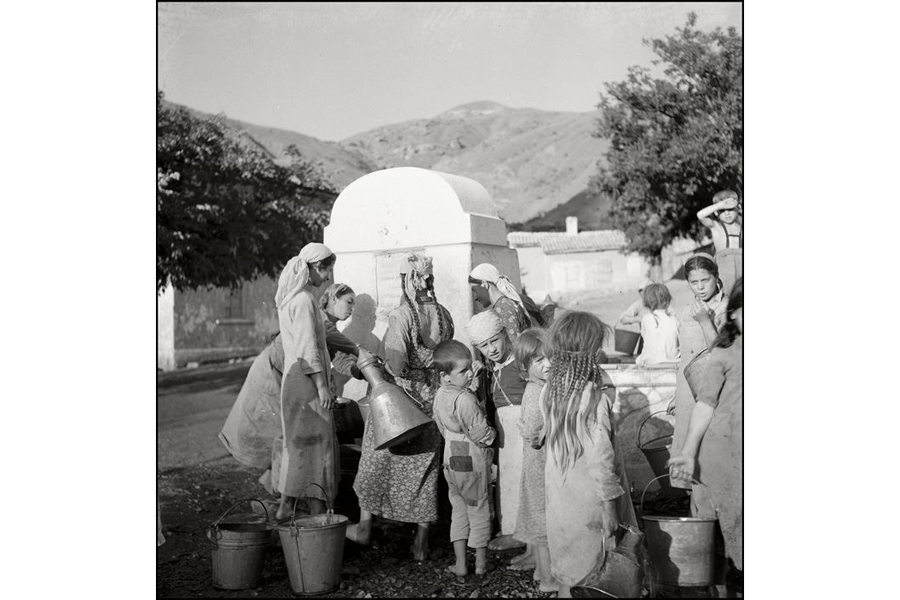

Crimean Tatars by a fountain, 1943. Photo: Herbert List / Magnum Photos.

The peninsula was governed by the Crimean Khanate, a vassal state of the Turkish-led Ottoman Empire, for over three centuries before the first Russian occupation. This state emerged after breaking away from the Golden Horde around 1441 and fell under Ottoman control after the 1475 conquest. Throughout its centuries-long existence, the Khanate established a political framework for the emergence of indigenous peoples, primarily the Crimean Tatars, who formed its dominant population. The widespread use of the Crimean Tatar and Turkish languages led other indigenous populations – the Karaites and Krymchaks – as well as local Greek and Armenian communities to adopt Turkic languages as well. The Crimean Khanate was renowned for its militant policies, which made it a key rival of the Russian Empire for dominance in the southern part of modern Ukraine.

Golden Horde

A political entity within the Mongol Empire that emerged in the 13th century after the Mongol conquests in Eastern Europe and Central Asia. It encompassed parts of modern-day Ukraine, Russia, Kazakhstan, and the Caucasus region.

“The Khan Palace in Bakhchisaray” by Carlo Bossoli, 1857. Source: Wikipedia.

Despite migration processes initiated by the Russian Empire following its conquest of Crimea, the peninsula retained its diverse, multinational character. According to the 1897 census, it was home to significant communities of Greeks, Armenians, Bulgarians, Jews, Germans, Poles, Estonians, Belarusians, Turks, Moldovans, and Azerbaijanis. So how did the memory of these peoples fade, with Russians now asserting that only they, or primarily they, have always been in Crimea? The answer lies in a deliberate policy of colonisation.

For centuries, the successive regimes of the Russian Empire, the Soviet Union, and modern Russia have implemented a strict Russification policy in Crimea. The first renaming of settlements began as early as 1783, several years after the first occupation. Initially limited to cities, this policy replaced historic Crimean Tatar names with names such as Yevpatoria, Sevastopol, Simferopol, and Feodosia — names that remain for the peninsula’s largest cities today. After deporting the Crimean Tatars in 1944, the Soviet regime completely erased all remaining Turkic place names and replaced them with fabricated Russian ones.

Successive Russian occupations also brought forced changes to the peninsula’s demographics. Indigenous Crimeans left due to oppression and harsh living conditions, and Russians and other peoples under Russian rule were resettled in the peninsula. Mass deportations also took place. The first forced displacement occurred in the late 18th century, even before the Russian Empire completed its conquest of Crimea, when Greeks were deported to the shores of the nearby Sea of Azov. Later, under Soviet rule, the Kremlin committed crimes against Crimea’s indigenous peoples by deliberately deporting them to Central Asia. In 1944, during World War II, Crimean Tatars, along with local Greeks, Armenians, Germans, and Bulgarians, were falsely accused of collaborating with the Nazis. Branded as “enemies of the people”, they were deported in cattle wagons, mainly to the remote Soviet republics of Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan in Central Asia. The deportees were not allowed to return to their homeland until 1989.

“Enemies of the people”

A propaganda label that Soviet authorities placed on individuals or groups considered threats to the regime to legitimise their persecution, imprisonment, or execution, particularly during political purges.

Protest in Bekabad, 1988. Source: krymr.com.

After the deportations, Russian became the dominant language in Crimea. As part of Soviet state policy, Russians were systematically moved into the homes left behind by displaced families. Unsurprisingly, by the 2001 census, nearly 1.2 million Russians lived on the peninsula, making up 58.3% of its population. Russia also sought to maintain a military presence in Crimea, often composed of individuals loyal to the regime. After Ukraine gained independence, many of these settlers refused to accept the new reality and even volunteered to collaborate with Russia.

Russians continue to erase history in Crimea today, conducting illegal excavations and transferring valuable artefacts to their museums. A well-known example is the Khan’s Palace in Bakhchysarai, a historic residence of the rulers of the Crimean Khanate, which served as a major political and cultural centre since the 16th century. In 2017 – three years after Russia’s annexation of Crimea – the Russian-established occupational authorities launched a so-called reconstruction of the palace, which in reality destroyed many unique features. Elmira Ablyalimova, the former director of the Bakhchysarai Historical and Cultural Reserve (a cultural institution that managed the site before the Russian occupation – ed.), claims that this damage is irreversible.

The Khan’s Palace is a stark yet not singular example of Russia’s aggression against authentic Crimean culture. In June 2024, Evelina Kravchenko, senior researcher at Ukraine’s National Academy of Sciences, reported that the Russians damaged the UNESCO World Heritage site of Tauric Chersonese by constructing new buildings on its grounds. Russia often calls this site “the cradle of Russian spirituality”, claiming it was where Prince Volodymyr the Great of Kyiv adopted Christianity for Kyivan Rus in the 10th century. However, in its original form, Chersonese does not align with Russian myths, so the occupiers are going so far as to reshape its remnants to suit their narrative of Russia’s eternal presence in Crimea.

Tauric Chersonese

An ancient Greek city that was founded by Greek colonists in Crimea in the 5th century BCE and remained active until the late 15th century AD. As one of the best-preserved Greek cities in the world, it was recognised as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2013.

Photo source: Russian propaganda media.

As we can see, life and civilisation in Crimea did not begin with the arrival of Russians. This territory was settled long before and became an integral part of both the European and Turkic worlds on its own. Indigenous peoples developed their own cultures, writing systems, and histories here. This rich heritage did not vanish in the 18th century, despite numerous Russian attempts to erase it in the following centuries. Nevertheless, Russia deliberately overlooks the peninsula’s true history and promotes the narrative that Crimea has always been Russian.

Myth 2: Crimean Tatars are not an indigenous people of Crimea

After the Crimean Tatars’ deportation in 1944, Soviet historians promoted a narrative suggesting that this group descended from the Mongol invaders who occupied Eastern Europe in the 13th century. They sought to portray the Crimean Tatars as settlers in Crimea and not an indigenous population and reinforce the myth of Russia’s perennial presence in the region.

This myth is based on the fact that the conditions for the formation of the Crimean Tatars did emerge as a result of the Mongol conquest. Indeed, the term Tatar people, the name of the Tatar language, and the toponym Crimea first appeared on the peninsula with the arrival of the Mongols. The Crimean Tatar ethnicity was initially established by the Crimean Khanate, a direct descendant of the Mongol Empire. Furthermore, the national consciousness of the Crimean Tatars began to develop under the influence of nationalist ideas in the late 19th century.

However, Crimean Tatars cannot be considered outsiders because they represent the nomadic herder civilisation of Eurasia, which dominated Crimea from prehistoric times. In fact, Crimean Tatars are the last representatives of this civilisation in Crimea. Migration, conquest, and the formation of new tribes and peoples have defined the history of this steppe civilisation, which once stretched from modern-day China in the east to Central Europe in the west.

The Crimean Tatars did not originate solely from the tribes that were brought to the peninsula by the Mongol conquest. Their lineage can be traced back to the Cumans, who ruled the steppes of Western Eurasia during the mid-11th century. Contemporary accounts recognise that at the time of the Mongol invasion, the descendants of the Cumans already made up the majority of the population in the Golden Horde steppes, and they later adopted the name Tatars.

Notably, the Mongol conquest established the political conditions that led to the formation of not only the Crimean Tatars but also modern Russians. In fact, the Grand Duchy of Moscow emerged around the same time as the first recorded mention of the city of Krym, now referred to as Staryi Krym (“Old Crimea”), which served as the administrative centre of the Crimean Tumen. This name eventually became associated with the Crimean Khanate and, in the 20th century, with the Crimean Tatars themselves.

Tumen

A basic administrative and military unit of the Golden Horde.

“Old Crimea” by Ivan Aivazovskyi. Source: culture.voicecrimea.com.ua.

It is essential to recognise that the indigenous people of Crimea, who have a long history, were largely absent from the peninsula for an extended period. This disappearance resulted directly from the genocidal policies first enacted by the Russian Empire and later by the Soviet Union. In fact, the Soviet authorities not only deported the Crimean Tatars but also aimed to destroy all evidence of their existence. It was not until the USSR started to collapse in 1989 that significant numbers of Crimean Tatars began to return to their homeland, influenced by the attitudes of both the government and the population of Soviet Ukraine. By the 2001 census, they constituted 12.03% of Crimea’s population.

Myth 3: Crimea was an accidental “gift” to Ukraine

This myth emerged in contemporary Russia, which has struggled to come to terms with its loss of control over Crimea. The peninsula officially became part of Soviet Ukraine in 1954. According to Russian narratives, this transfer occurred because Nikita Khrushchev, the then-leader of the Soviet Communist Party and de facto ruler of the USSR, supposedly decided to “gift” Crimea to Ukraine while inebriated during a celebration — an act that many Russians now consider “a mistake” and “theft”. However, it was the Soviet government, not Khrushchev alone, that enacted the decree for the transfer of Crimea. During the meeting of the Communist Party’s Central Committee on 25 January 1954, where the decision was approved, Khrushchev was not even formally in charge. That role belonged to Georgy Malenkov, then Premier of the Soviet Union.

Stalin and Malenkov. Source: Russian propaganda media.

The transfer of Crimea was not an overnight decision, either: it had been in the works since at least autumn 1953 and was driven by pragmatic considerations. Following World War II and the deportations, the peninsula experienced significant economic decline. Its geographical isolation from Moscow and the rest of Russia, combined with the newly settled Russians’ lack of preparedness to cultivate the Crimean land or secure clean water, exacerbated the situation.

Historian Petro Volvach illustrates the dire state of Crimea during this period, noting that by the end of 1953, only three bakeries were operational on the peninsula. Consequently, it made sense for Soviet leadership to transfer Crimea — an area in dire need of substantial human and material resources for recovery — from Soviet Russia to another republic for closer oversight. Following the transfer in 1954, Soviet newspapers reported that cities across Ukraine were dispatching machinery and materials to aid in the post-war reconstruction of the peninsula.

Release of water at Simferopol Reservoir, 27 December 1955. Source: Babel.

However, Crimea is connected to mainland Ukraine not just geographically — through the Perekop Isthmus and other similar natural features — but also by a shared history that spans centuries. This common past has played a crucial role in shaping the internationally recognised borders of Ukraine today. In fact, Crimea embodies the historical narrative of Ukraine itself. The transfer of Crimea to Soviet Ukraine in 1954 was merely one act in a longer history of exploitation, where the rulers of the Russian Empire and the Soviet Union used Ukrainians for the colonisation and economic development of steppe lands across the Caucasus, Siberia, and the Far East. Between the 14th and 20th centuries, Ukrainians actively settled the steppe areas in the south of modern-day Ukraine, transforming it into a Ukrainian homeland. Their success can be attributed to adopting cultural practices from the nomadic herders of the region — specifically, the Crimean Tatars and Turks. They integrated military knowledge, skills, everyday customs, and elements of political culture from these communities into their own. The Ukrainian development of the steppe marked the culmination of the interactions and rivalries between nomadic and settled civilisations in the territory, serving as one of the earliest examples of agricultural colonisation in the steppes. To this day, the legacy of these processes is evident in Ukraine’s reputation as a European granary.

The history of interactions between Ukrainians and Crimean Tatars is rich and complex, marked by both cooperation and conflict over the centuries. These two groups have shared a longstanding connection rooted in the geographical and cultural landscapes of the region.

Throughout history, Ukrainians and Crimean Tatars have often collaborated in the face of common threats. For instance, during the 17th century, Ukrainian Kozaks and Crimean Tatars formed alliances to resist external forces and defend their autonomy. These alliances were crucial in military conflicts.

Kozaks

A warrior social class and democratic self-governing military entity that emerged in the 15th century in the territories of modern-day Ukraine, primarily for frontier defence. The Kozaks played a pivotal role in establishing the Kozak Hetmanate, an autonomous Ukrainian state, during the 17th century.Later, the connection between Crimea and Ukraine was affirmed in the 1710 Constitution of Pylyp Orlyk. This document highlights the Crimean Khanate’s important role in helping Kozak troops liberate Ukrainian lands from Polish rule. It also underscores the necessity of establishing diplomatic relations between Ukraine and Crimea, stating:

“It is vital that the Honourable Hetman (the supreme political ruler and military commander of the Kozak state – ed.), through his envoys to His Most Serene Majesty the Crimean Khan, works to restore the ancient brotherhood and military unity with the Crimean state and to confirm eternal friendship, so that neighbouring states would not dare to attempt to subjugate Ukraine or ever act violently against it.”

In addition to historical accounts, the connection between these peoples can also be found in Ukrainian folklore. Russia uses this fact to portray Crimean Tatars as eternal enemies of Ukrainians, but it actually reveals a noteworthy point: there is no Russian folklore associated with Crimea and the Crimean Tatars. Instead, Russians exploit Ukrainian folklore for their own purposes, aiming to sow discord between Ukrainians and Crimean Tatars. In Ukrainian folk culture, Crimea is often referenced in diverse and rich contexts.

“Bohdan Khmelnytsky with Tugay Bey near Lviv” by Jan Matejko, 1885. Source: Wikipedia.

This connection between the peoples continued during the Ukrainian Revolution of the 20th century, when the Crimean Tatars recognised that they could only maintain their autonomy if they remained in Ukraine. This trend persisted during Ukraine’s return to independence in 1991. During the nationwide referendum, 54.19% of Crimea’s population voted in favour of Ukraine as an independent state. Therefore, from a legal standpoint, the peninsula chose to remain within the borders of sovereign Ukraine.

Myth 4: The people of Crimea wanted to “reunite” with Russia

This myth primarily centres on the referendum orchestrated by the Russian-imposed authorities shortly after their occupation of the peninsula in 2014. The narrative often overlooks that Crimea had voted for Ukraine’s independence and its rightful place within it during the 1991 referendum. Additionally, there are other facts that disprove the popularity of separatist sentiments among the Crimean Tatars, indicating that these sentiments primarily originate from Russians.

After the collapse of the Russian Empire in 1917, Ukrainians and Crimean Tatars supported one another in their aspirations to establish their own national states — the Ukrainian People’s Republic and the Crimean People’s Republic. At the Congress of the Oppressed Peoples of Russia in Kyiv in 1917, the Crimean Tatar delegation expressed their desire to join the Ukrainian People’s Republic. Ukrainian cultural societies were also active in Crimea at this time, hosting performances and concerts in the Ukrainian language. Furthermore, the Ukrainian parliament recognised the Crimean Tatars as the main group who wanted self-determination in Crimea. The Crimean Tatars swiftly established their own national government, the Muslim Executive Committee, led by Noman Çelebicihan. However, both states turned out to be short-lived. After being defeated by Russian troops, they were both abolished and incorporated into the newly established USSR in the 1920s.

The first Crimean Kurultai. Source: Wikipedia.

Kurultai

The main representative body of the Crimean Tatars — a nationwide assembly for addressing important issues.

Ukraine has been and remains a multinational state — this is how history has unfolded. However, its inhabitants have always respected territorial integrity, and even if they belonged to different ethnic groups, they understood the importance of independence. Therefore, the claim that separatist sentiments originated in Crimea is entirely incorrect. The illegal referendum and occupation in 2014 were the result of Russia’s systematic influence, which began the moment Ukraine gained independence. As early as 1992, the Russian Supreme Council declared the 1954 transfer of Crimea to Ukraine illegal. Later, Russia stationed its fleet on the peninsula, and in 2003, it attempted to seize nearby Tuzla Island, forming and sponsoring local organisations advocating for Crimea’s transfer to Russia. Thus, in addition to Russia’s direct military aggression, the 2014 occupation of Crimea also resulted from Russia’s investment in propaganda and systematic efforts against Ukrainian statehood.

Russian authorities often claim that the so-called annexation was bloodless and that the population did not resist the Russian troops. However, on 26 February 2014, between 5,000 and 10,000 Crimean residents gathered outside the Crimean Parliament building in Simferopol (the administrative centre of Crimea – ed.) to support Ukraine’s territorial integrity and protest the unfolding annexation. During clashes between pro-Ukrainian and pro-Russian demonstrators, two people were killed. Later, after the occupation was complete, the Russian-established occupation administration accused nine Crimean Tatars of “organising and participating in mass riots” on that day. In March, Crimean Tatar activist Reshat Ametov, who staged a solo protest against the illegal actions of the “little green men”, was murdered. There were also casualties among the military: during the assault on the Simferopol Photogrammetric Centre, Russian special forces shot and killed Ukrainian serviceman Serhii Kokurin. His murder is considered the first death in the Russo-Ukrainian war.

little green men

A phrase that came into use during Russia’s 2014 annexation of Crimea, referring to Russian soldiers who occupied the region while wearing military uniforms without any identifying insignia.

Protest in Simferopol, 26 February 2014. Photo: Stas Yurchenko for RFE/RL.

The referendum was organised by the Russians on 16 March 2014 to supposedly confirm Crimea’s desire to secede from Ukraine was illegal under Ukrainian law. It was also recognised as illegal by the UN Security Council and the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). In addition to the fact that it was conducted under armed threat, Russian citizens were illegally brought in to vote for annexation. Therefore, the results cannot be considered objective, nor can it be claimed that Crimean residents genuinely wanted to become part of Russia.

Since the onset of the modern occupation in 2014, Crimea has witnessed repressions reminiscent of the Soviet purges. Any pro-Ukrainian stance on the peninsula has been strictly prohibited, with locals facing the threat of imprisonment or even death for expressing such views. According to the Crimean Tatar Resource Centre, as of April 2024, Russia has taken 320 Crimean residents as political prisoners; 217 of them are Crimean Tatars.

Illegal searches at a mosque in the city of Staryi Krym, 29 February 2024. Source: Crimean Solidarity.

Russia has also been exploiting residents of Crimea in its war against Ukraine. Local residents have faced illegal conscription into the Russian army since 2015, with mobilisation efforts increasing in September 2022. To escape conscription, many Crimean Tatars have fled the peninsula. Refat Chubarov, head of the Mejlis of the Crimean Tatar people, estimates that by April 2024, between six and eight thousand had left. He also reported that by June 2024, around one thousand people from Crimea had been killed while serving in the occupying forces. Meanwhile, Russia is actively militarising children on the peninsula through “military-patriotic” education programmes and the Youth Army, a paramilitary organisation established by the Russian defence ministry in 2016 that is accused of the widespread militarisation of Ukrainian children in the occupied territories.

The Mejlis of the Crimean Tatar people

A central representative body elected by Crimean Tatars to address the political, cultural, and social needs of the community. Established after Ukraine's independence in 1991, the Mejlis was outlawed in Russian-occupied Crimea in 2016.

Youth Army members in Crimea. Source: RFE/RL.

Despite all of this repression, the residents of Crimea who have managed to preserve their identity continue to resist. They engage in subversive activities and collaborate with the Armed Forces of Ukraine, displaying blue-and-yellow flags and participating in the Yellow Ribbon movement.

Yellow Ribbon movement

A grassroots initiative in the occupied territories of Ukraine expressing support for Ukraine’s sovereignty by putting up yellow ribbons in public spaces.

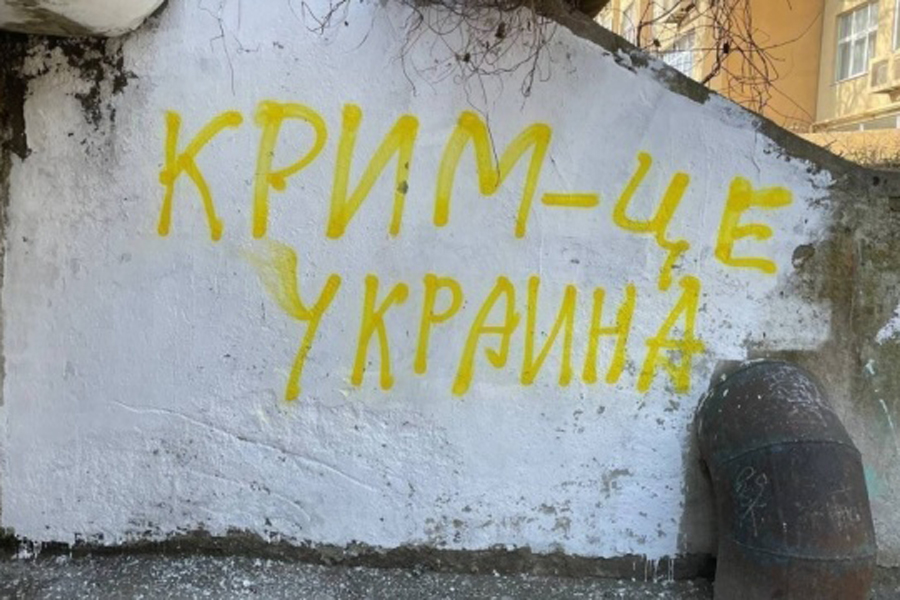

"Crimea is Ukraine". Photo source: Yellow Ribbon movement.

Russia continues to exploit Crimea to propagate myths that serve its interests. By fabricating narratives about the peninsula, it constructs an artificial Russian continuity in its history, denies Crimea’s connections to Ukraine, and tries to justify its armed aggression. Russia has firmly entrenched its fabricated claims to the territories and resources of subjugated peoples on the global political stage, and understanding the history of Crimea, in particular, will be crucial in challenging this colonial narrative.