For many Ukrainians, 2014 marked a pivotal moment that set in motion rapid changes in both their country and their lives. The Revolution of Dignity succeeded in toppling the pro-Russian president Yanukovych and putting an end to his destructive policies. That same year, Russia annexed Crimea and launched a war in the east of Ukraine. For more than a decade, Ukraine has been resisting Russian aggression in its many forms. At the outset of the war, Ukraine was in a deeply challenging political, economic, and social condition, and likely appeared an easy target for the aggressor. Despite enduring continuous conflict with a powerful enemy, the nation has managed to preserve its sovereignty, demonstrate resilience in the face of adversity, and gain invaluable experience in reclaiming its territory.

Ten years ago, the vision for Ukraine’s future was vastly different from what it is today. Many of Ukraine’s politicians held pro-Russian views, with their decision-making often shaped by the country’s reliance on the Russian Federation. At that time, most Ukrainians were only beginning to rediscover their national identity and forge a collective sense of purpose, which involved a deeper understanding of the importance of language and culture. Ukrainians were grappling with the legacy of their coexistence with the empire and its lasting influence on their collective consciousness.

In addition to facing external challenges, Ukraine has implemented a series of reforms and fostered cooperation across various sectors over the past ten years. The pace, focus, and quality of these actions may still be open to debate, but during this difficult period, the country has undergone significant changes. In recent years, the state has strengthened its sovereignty in the eyes of the international community and gained support from foreign partners. Meanwhile, Ukraine’s economy, politics, culture, and military have finally rid themselves of Russian influence. In this piece, we revisit the key state and societal changes from 2014 to February 2024.

Photo: Viacheslav Ratynskyi

How the Ukrainian army has been reforming under fire

A reformed and more powerful Ukrainian army is one of the key achievements of the past decade. When you are neighbouring a terrorist state, your defence capabilities are crucial for both survival and reform. Since 2014, the Ukrainian Army has undergone one of the most dramatic transformations in its modern history, both in terms of size and quality.

In 2013, a number of military experts backed up by servicemen pointed out weaknesses in the Armed Forces of Ukraine (AFU), including a lack of financing, a legacy of Soviet standards, an urgent need to update technologies, and insufficient social support for the soldiers. Russia’s military occupation of Ukraine’s territory, where they seized weapons, military equipment, and other resources for their further advancement in the war, also undermined the capacity of the Ukrainian army.

Under these dire circumstances, the Ukrainian army managed to muster its strength, with some people responding to the draft call while others volunteered to become soldiers. Still, there was another group who, working as volunteers, took it upon themselves to supply the army with food, arms, equipment and camouflage nets. Along with local charitable initiatives and fundraisers, organisations and funds arose to support the military systematically. Those were the likes of Come Back Alive, Army SOS, Motohelp, Zgraya and others. The experience gained back then became an important asset after the Russian Federation launched a full-scale war in 2022. By that moment, Ukrainians had gained understanding of how to set up an aid system, charitable organisations had grown their own communities, and the culture of donations and charitable work scaled up.

Photo: Karina Piliuhina

The transformative change of the Ukrainian Defence Forces began with military reform in 2014. The reform aimed to break away from the Soviet legacy, enhance the country’s defence by adopting NATO principles and standards, and improve the efficiency of planning and resource management systems.

Introducing NATO standards to military training

After proclaiming its independence in 1991, Ukraine has participated in numerous international drills. Since 2014, the country has significantly increased its joint military exercises with NATO membering states, including the USA, Poland, Romania, Turkey, Italy, and others. Among these, Operation Orbital stands out for its scale and the number of troops involved, with British instructors training over 22,000 Ukrainian servicemen between 2014 and 2022. Despite the full-scale invasion, in the summer of 2022, Operation Orbital was relocated to the UK to continue the training.

Following the British instructors’ example, military personnel from countries like New Zealand, the Netherlands, Canada, and others also moved their training operations for Ukrainian soldiers. Operation Unifier, which will continue until 2026, involves the Canadian Armed Forces running boot camps for Ukrainian troops. This operation makes up a crucial part of an international joint effort aimed at reforming the Ukrainian army.

Photo: Valentyn Kuzan

Building a stronger Ukrainian army

Since 2004, the Ukrainian army has consisted of three main branches: the Ground Forces, the Air Force, and the Navy. The most recent reforms introduced several additional branches, including the Special Operations Forces, the Highly Mobile Air Assault Forces (rebranded as the Air Assault Forces in November 2017), and the Territorial Defence Forces.

Additionally, nearly two dozen combat brigades were established, alongside new regiments, battalions, and units for operational, combat, rear, and technical support. The number of troops grew rapidly to 250,000 before the full-scale invasion, and surged to 700,000 after February 2022. As of January 2024, according to an interview with Volodymyr Zelenskyy for the German broadcaster ARD, the Ukrainian army had expanded to 880,000 soldiers, including both men and women.

Compared to 2014, the number of women in the Ukrainian army has also risen significantly. According to the Personnel Centre of the Armed Forces of Ukraine, by October 2023, the number of female soldiers in combat positions had also increased.

Photo: Mykyta Zavilinskyi

Boosting domestic arms manufacturing

Over the past decade, Ukraine has developed and produced a variety of new weapons and equipment, which have been used by its forces alongside foreign supplies. Some examples that have been made public are listed below.

In 2009, the Ukrainian company Research and Manufacturing Association PRACTICA began producing the Kozak armoured personnel carrier, with several models available. This vehicle has been deployed to the Ukrainian Armed Forces, the National Guard, and the State Border Guard Service. Known for its high mobility, the Kozak is equipped with armour capable of withstanding 7.62 calibre bullets. Additionally, it can be outfitted with a variety of weapons, enhancing its versatility in combat.

The Leleka-100, an unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) developed by the Ukrainian company Derivo, comes in several modifications. It is valued for its compactness, cost-effectiveness, and efficiency in combat situations. The Leleka-100 provides critical reconnaissance and surveillance capabilities.

Photo: Volodymyr Pashchuk for the Come Back Alive Foundation

The Ukrainian self-propelled artillery system (SPG) “Bohdana” was designed for a 155mm calibre, in line with NATO standards. The first prototype was unveiled on 14 July 2018. “Bohdana” saw its combat debut during the liberation of Zmiinyi Island in the summer of 2022. Alongside artillery provided by Western partners, it was used to fire on enemy positions. In early 2023, Ukraine secured funding for the serial production of updated models of the “Bohdana”.

How allied nations are supporting Ukraine’s military

Innovations and changes in combat tactics have driven the need for modern weapons. In 2018, the USA sold 37 Javelin launchers and 200 missiles to Ukraine, followed by another delivery in 2019 of 10 more launchers and 150 missiles.

As the full-scale war unfolded, the Ukrainian Armed Forces (AFU) increasingly relied on Javelins, supplied by the allies. In addition, the Swedish-British NLAW anti-tank guided missile systems and man-portable air defence systems (MANPADS) such as the FIM-92 Stinger saw high demand. As the war progressed, Ukraine’s requirements expanded to include artillery and armoured vehicles. In May 2022, the USA, Canada, and Australia supplied the AFU with approximately 100 M777 howitzers, a critical contribution that helped Ukrainian forces successfully repel Russian advances in the east of the country.

Another significant delivery during the full-scale war was the M142 High Mobility Artillery Rocket System (HIMARS), which enabled the Ukrainian forces to target large concentrations of Russian troops and ammunition depots, even in the rear areas of the frontline. This system provided the ability to strike with precision at greater distances, greatly enhancing Ukraine’s offensive capabilities. By July 2023, Ukraine had also received dozens of Leopard tanks in various modifications from its allies. These tanks are renowned for their superior armour, manoeuvrability, and advanced fire control systems.

In addition to the equipment used for striking Russian positions, Ukraine was supplied with air defence systems to counter aerial attacks: the NASAMS, IRIS-T, and Patriot missile systems successfully intercepted cruise missiles, as well as ballistic missiles, which was unprecedented in terms of the confrontation between Russian and Western weaponry. These deliveries significantly strengthened Ukraine’s air defence forces (PVO), which, before the full-scale invasion, could intercept no more than 18% of incoming cruise missiles.

Photo: Oleh Marchuk

Ukraine’s Western integration after 2014

Before Ukraine pursued closer ties with the EU, it had long been closely aligned with Russia across various sectors. However, over time, the Ukrainian people’s growing aspirations for independence and European integration led to a gradual separation from the Kremlin. This shift was further accelerated after Russia’s initial invasion in 2014.

Advancing Ukraine-EU relations

The process of preparing to sign the Association Agreement with the European Union — the largest international legal document in Ukraine’s history — began in 2007. Over the following years, representatives from both sides held a series of meetings, which successfully concluded in the autumn of 2013. However, just days before the final signing, Ukraine’s government at the time, along with President Viktor Yanukovych, halted the preparation process and announced that the agreement with the EU would not be signed.

The refusal to sign the agreement sparked mass protests known as the Revolution of Dignity, which began in the autumn of 2013. Initially a peaceful movement in support of Ukraine’s European course, the protests quickly grew into a national demonstration against corruption and abuses of power by the pro-Russian government of the time. This ultimately led to President Viktor Yanukovych fleeing to Russia — a move the Kremlin used as a pretext for its invasion of Ukraine.

After the 2014 Revolution of Dignity and the flight of President Yanukovych, efforts to sign the EU Association Agreement were reignited. In the spring of 2014, Ukraine and the EU signed the political association and economic integration components of the agreement, which were ratified by the Ukrainian Parliament on 16 September. By March 2023, Ukraine had completed 72% of its obligations under the agreement. According to Olha Stefanyshyna, who was Ukraine’s Deputy Prime Minister for European and Euro-Atlantic Integration at the time, the process of aligning Ukrainian legislation with EU standards has continued, even amidst the full-scale war.

Securing visa waiver agreements with the EU

The visa-free regime with the EU, adopted at the end of 2016, marked the next step in Ukraine’s cooperation with the European Union. It allowed Ukrainians to travel (for up to 90 days) to various EU countries without a visa for short-term visits. Despite the full-scale war in 2024, Ukraine’s foreign passport ranked 32nd in the global Passport Index by Henley & Partners. The country was among the top five nations with the most significant improvements in passport strength over the past decade.

Verifying EU candidate status

On 28 February 2022, European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen expressed support for Ukraine’s accession to the EU. In April 2022, the Ukrainian government received a detailed questionnaire from the European Union, which was to be worked on as part of obtaining EU candidate status.

Two months later, in an official statement by the European Commission, Ukraine was recognised as a potential candidate for EU membership. To maintain this status, a number of specific reforms needed to be implemented, including: the reform of the Constitutional Court of Ukraine, judicial, anti-oligarchic, and law enforcement reforms, anti-corruption measures, and the creation of laws on media and national communities. Ukraine continues to implement some of these changes to this day: as of November 2023, experts from the European Commission assessed that 4 out of 7 candidate requirements had been fulfilled.

Photo: Viacheslav Ratynskyi

Shortly after the European Commission’s recommendation, on 23 June 2022, the European Parliament passed a resolution supporting Ukraine’s EU candidacy. That same day, the European Council made the final decision to grant Ukraine candidate status. On 14 December 2023, the European Council officially launched negotiations on Ukraine’s accession to the European Union.

International recognition of the Holodomor

The recognition of the Holodomor of 1932–33 — one of the most massive crimes of the Soviet regime — as an act of genocide became particularly urgent after 2014, as it was at this time that the international community began to delve deeper into the Ukrainian context and the underlying causes of the Russo-Ukrainian war. This recognition became a gesture of solidarity and support for Ukraine in its struggle against Russia.

The Holodomor, meaning “death by hunger”, was a man-made famine caused by the Soviet regime’s deliberate policy of collectivisation. According to estimates from Ukraine’s Institute of Demography and Social Studies, the forced confiscation of land and grain in Soviet Ukraine led to the deaths of 3.9 million people, the vast majority of whom were peasants.

The Soviet leadership channelled the resources gained from collectivisation into industrial development, helping to establish the USSR as one of the world’s largest economies. However, for Ukrainians, the Holodomor meant more than just the loss of economic potential; it devastated traditions and cultural identities, which were lost alongside the lives of countless men, women, and children.

In 2006, Ukraine officially recognised the Holodomor as a genocide.

In 2018, the United States Senate passed a resolution unanimously acknowledging it as such. Following the events of 2022, parliaments in Brazil, Ireland, Moldova, Germany, and the Czech Republic also recognised the Holodomor as genocide. In 2023, further recognition came from the parliaments of Bulgaria, Belgium, France, Iceland, the United Kingdom, Slovenia, Slovakia, Croatia, Luxembourg, and the Netherlands, as well as Italy’s Senate. As of November 2023, a total of 30 countries worldwide had recognised the Holodomor as genocide at the parliamentary level.

During the full-scale invasion of Ukraine, documenting Russia’s crimes became a top priority to ensure accountability for the aggressor state. In April 2022, Ukraine’s Verkhovna Rada adopted the “Declaration on the Commission of Genocide by the Russian Federation in Ukraine, No. 2188-IX”, urging international organisations and the parliaments of other countries to recognise Russia’s actions in the war against Ukraine as genocidal.

slideshow

This call was backed by the parliaments of Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, the Czech Republic, Ireland, and Canada, as well as the EU and NATO Parliamentary Assemblies. In addition, the EU Parliamentary Assembly, along with Estonia, Poland, Slovakia, and the Czech Republic, officially designated Russia as a terrorist state. In June 2022, the EU, joined by 43 other countries, issued a Joint Statement supporting Ukraine’s case against Russia at the UN International Court of Justice under the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide.

Ukraine’s NATO accession

Ukraine officially applied for the NATO Membership Action Plan in 2008. At the Brussels summit in June 2021, NATO leaders reaffirmed their decision to recognise Ukraine as a US Major Non-NATO Ally. On 30 September 2022, amid the ongoing full-scale war, Ukraine formally submitted an application for an expedited path to NATO membership.

To enhance cooperation between Ukraine and NATO, particularly in cybersecurity, intelligence sharing, defence reform, and military training, the NATO-Ukraine Council (NUC) was established. This body facilitates political dialogue and coordinates the reforms required for Ukraine’s eventual NATO membership.

Vilnius NATO Summit 2023. Photo source: Nato.int.

The NUC also provides the political framework for the Ukraine Defense Contact Group (UDCG), also known as the Ramstein Group. This alliance, consisting of NATO member states and its partner nations, coordinates the ongoing donation of military aid through monthly meetings. The first meeting was held on 26 April 2022 at the Ramstein Air Base in Germany, the largest US Air Base in Europe. Since then, the Ramstein Group has become a key platform for aligning international support. This assistance has been crucial in halting the Russian advance and driving them back. By April 2024, representatives from 50 countries had pledged a total of $95 billion in support.

Ukraine’s domestic policy

Spearheading anti-corruption effort

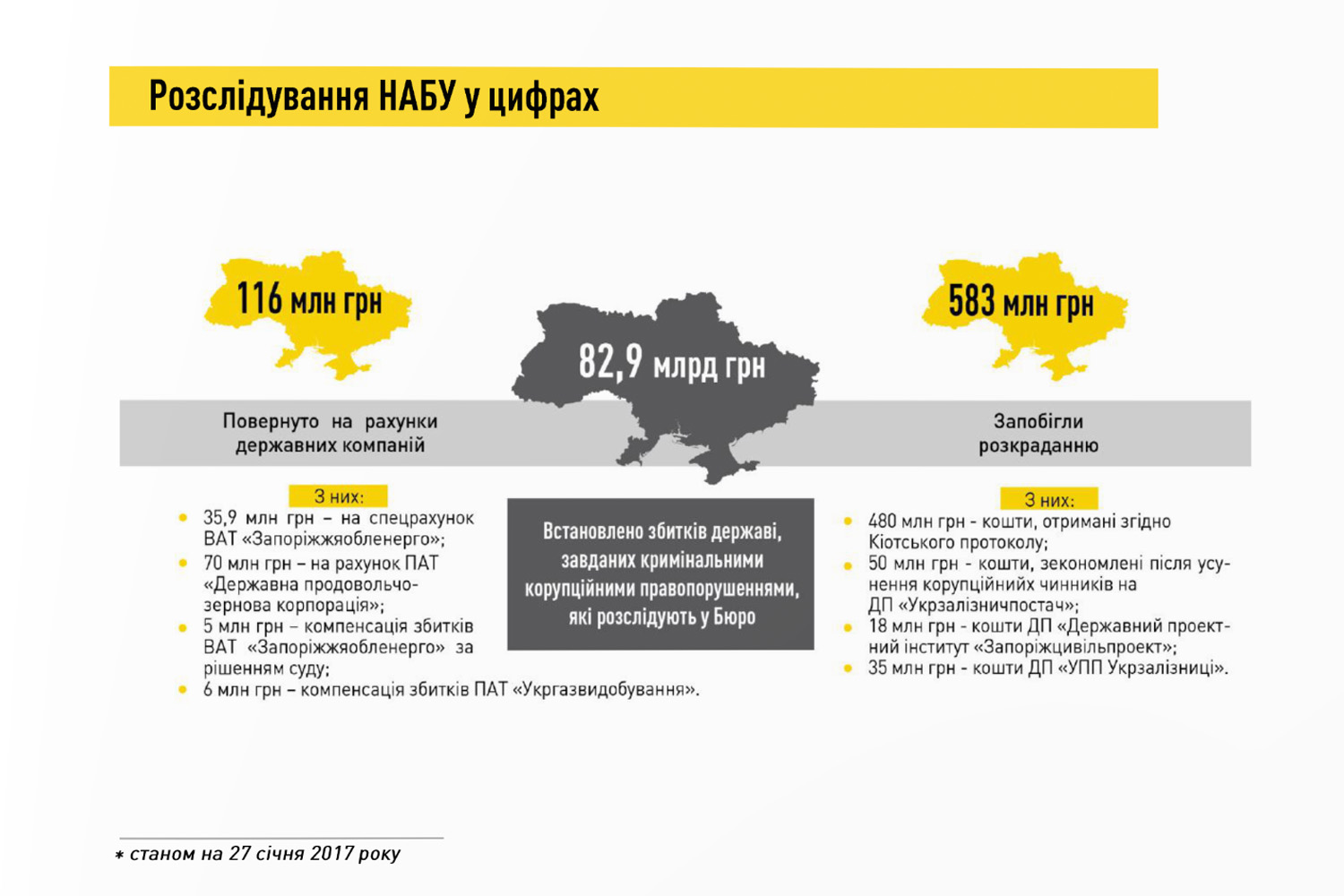

Since 2014, Ukraine has started to build a system of anti-corruption institutions as part of its reforms for EU integration. Over the following years, several key bodies were established, including the National Agency for Corruption Prevention (NACP), the Specialized Anti-Corruption Prosecutor’s Office (SAPO), the State Bureau of Investigation (SBI), the National Anti-Corruption Bureau of Ukraine (NABU), and the High Anti-Corruption Court (HACC). Additionally, the government introduced online tools to combat corruption: the Prozorro system helps monitor public procurement, while the Unified State Register of Declarations allows access to information about the incomes and assets of individuals holding particularly responsible positions or working in high-risk corruption sectors.

Prozorro

Ukrainian public electronic procurement platform that was implemented in 2016 to ensure open access to public procurement (tenders), minimising corruption risks.

Screenshot of a brochure detailing the activities of the NABU.

During the full-scale war, several institutions adjusted their operations to address new realities and priorities. For example, through the National Agency for Corruption Prevention (NACP), the assets of Russians in Ukraine were frozen. Over the two years of the full-scale invasion, court rulings led to the confiscation of assets worth over UAH 5 billion (roughly $135 million – ed.), which were redirected to the state. Meanwhile, the State Bureau of Investigations (SBI) focused its efforts in the newly liberated areas, uncovering officials who had betrayed the country and defected to the enemy.

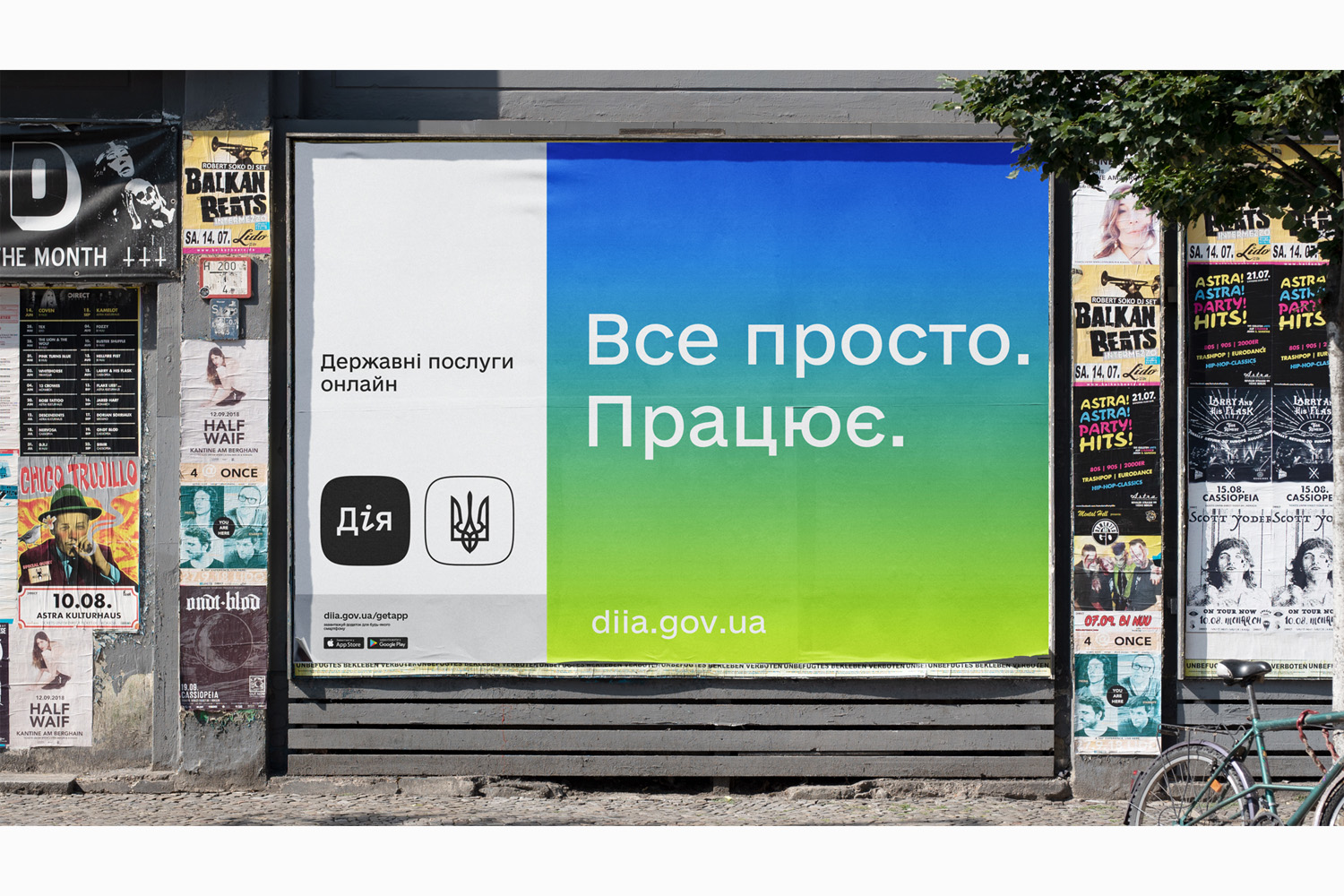

Launching E-Government

Since 2014, Ukraine has made significant strides in developing digital platforms. The country established the Ministry of Digital Transformation, expanded electronic resources, and introduced e-documentation processes. These initiatives have greatly simplified access to a range of public services and enhanced the protection of state information systems.

In the past four years, Ukraine has climbed from 82nd to 46th place in the Global Government Digitalisation Index. At the 2022 Davos Summit, it was even recognised as Europe’s “digital tiger”.

Image source: Press service of the Diia portal.

One of the standout projects by the Ministry of Digital Transformation is Diia, a multifunctional portal that has transformed how citizens interact with the State. Beyond offering digital versions of official documents, Diia provides a wide range of services for Ukrainians of all ages, many of which were previously only accessible in person. Since the onset of the full-scale invasion, Diia has been further enhanced to include features such as the ability to access financial compensation and apply for grants to start a business.

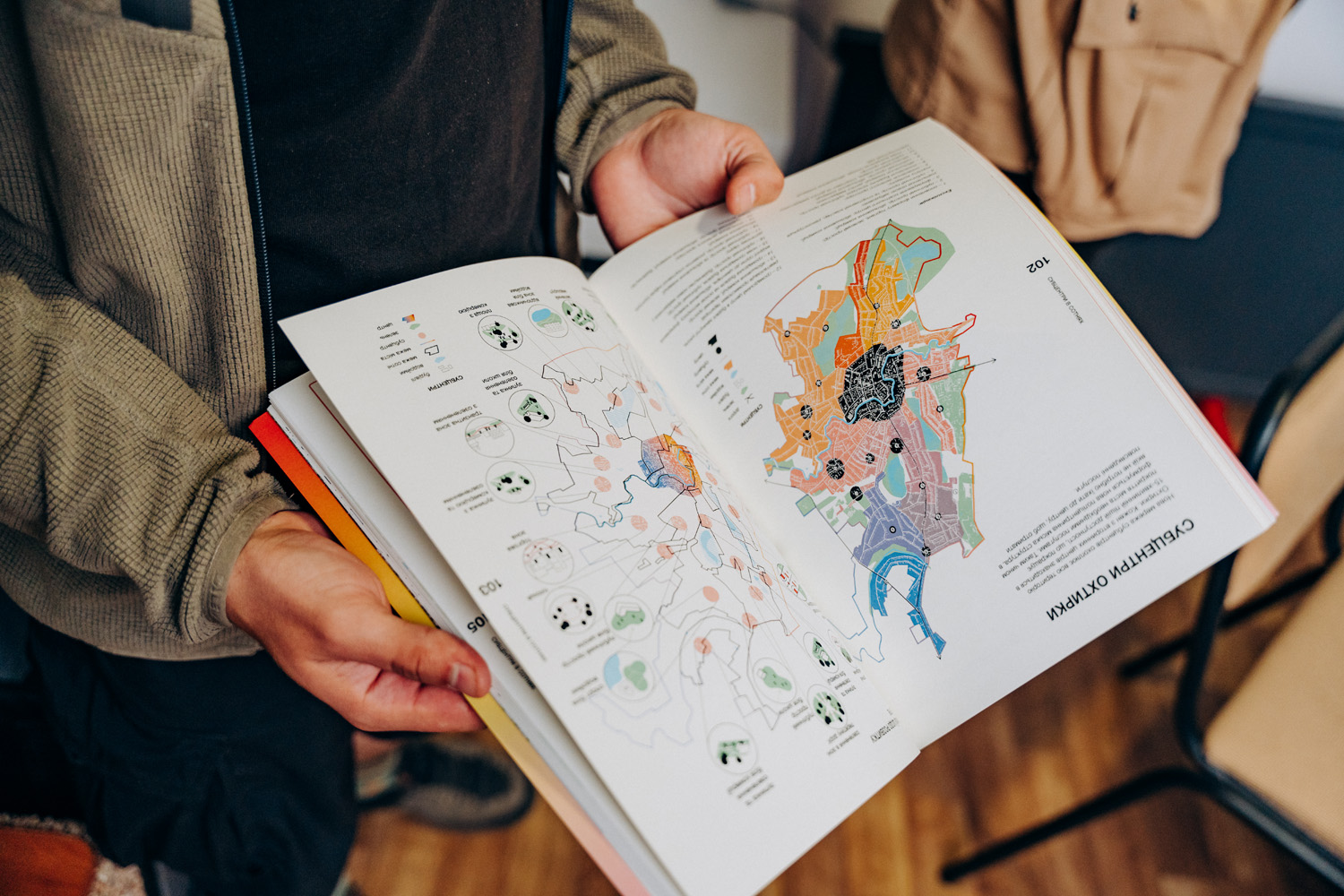

Empowering communities through decentralisation

In April 2014, the Ukrainian government implemented a reform of local self-government and territorial organisation of power — marking the beginning of the creation of amalgamated territorial communities (ATC). This reform aimed to increase the influence of local communities in decision-making at the local level and the distribution of local budgets.

By 2024, there were 1,439 active ATCs, covering 27,883 settlements. The reform has enabled local governments to operate more independently, giving them greater control over infrastructure development, management of communal property, and budget allocation. For example, in 2023, ATCs donated more than UAH 16 billion (approximately $432 million – ed.) to support the Armed Forces of Ukraine.

Diia

is a Ukrainian e-governance ecosystem that allows citizens to utilise 14 types of digital documents and access over 120 governmental services online. Since its introduction in 2020, the service has been used by over 20 million Ukrainian citizens.

Photo: Sofiia Soliar

Reforming law enforcement system

Ukraine’s Ministry of Internal Affairs began its reform in 2014, marking one of the most significant and difficult steps in overhauling the Soviet-era law enforcement system. The reform aimed to transform the Ministry into a modern, transparent, and effective institution in line with European standards. The reform focused on dismantling the Soviet-era militia, the primary law enforcement agency, and replacing it with the National Police, which was founded on principles of the rule of law and community engagement. This reform also included improvements to police training, the introduction of new protocols and procedures, and a stronger focus on protecting human rights, ensuring the force was better equipped to meet the needs of a modern democratic society.

Militia

heavily militarised, authoritarian Soviet-period law enforcement system, focused on bureaucracy and procedures, with minimal public oversight of its activities.

Photo: Yurii Stefanyak

The reform also introduced mechanisms for public oversight, ensuring that the police were held accountable to the local communities they served. To facilitate monitoring and transparency, supervisory boards, hotlines, and online services were established, providing citizens with direct ways to report misconduct or provide feedback.

Moreover, significant changes were made to the criminal justice system. New legislation was enacted to enhance criminal investigations, combat corruption, and ensure fair trials, strengthening the rule of law and helping Ukraine meet European standards in its judicial processes.

Photo: Oleksii Karpovych

Combating colonial legacy via decolonisation

On 21 May 2015, four decommunisation laws came into effect in Ukraine, which resulted in the deregistration and eventual dissolution of pro-communist parties. This was a crucial step in safeguarding Ukraine’s internal security, as these parties had advocated for cooperation with Russia and promoted hostile narratives.

The process also saw the gradual removal of monuments to communist figures and the dismantling of communist symbols. Over time, the renaming of streets and settlements was initiated. By 2021, over 51,000 toponyms had been renamed, 991 settlements had changed their names, and around 2,500 monuments and memorials with symbols of the communist totalitarian regime had been dismantled. After 24 February 2022, the process of decommunisation evolved into decolonisation, during which Ukrainians aimed to eliminate the remnants of the “Russian world” from their environment.

“Russian world”

is a Russian colonial narrative which promotes the annexation of states neighbouring Russia based on their affiliation with the Russian language, culture, and shared history.

slideshow

Introducing national human rights strategy

Originally adopted in 2015, Ukraine’s human rights strategy was revised in 2021 to better reflect the ongoing challenges posed by Russia’s long-term military aggression. The revised strategy places particular emphasis on the rights of veterans, internally displaced persons (IDPs), residents of temporarily occupied territories, those missing in action, and the families of civilians reported as missing. Its implementation is designed to strengthen Ukraine’s commitment to human rights, particularly in the context of its international obligations under agreements such as the EU Association Agreement.

Making healthcare accessible

Ukraine’s medical reform, launched in 2016, aimed to transform the outdated healthcare system inherited from the Soviet Union, which had confined patients to receiving free state healthcare only at their registered place of residence. This system limited access to medical services from doctors outside one’s local healthcare institution. The new reform prioritised the patient, granting them the freedom to choose their family doctor, paediatrician, or therapist regardless of where they lived. These healthcare professionals now serve as the first point of contact, overseeing patient care and coordinating further treatment when needed.

Additionally, the reform linked state funding for healthcare facilities to the number of patients they served, incentivising institutions to provide quality care and compete for patient loyalty. It also eased the bureaucratic burden on doctors by introducing online appointment systems, which allowed them greater autonomy in making treatment decisions for their patients.

As part of the reform, Ukraine launched several important state programmes aimed at making healthcare more accessible to all citizens. One such initiative is the Medical Guarantee Programme, introduced in 2020. Its goal is to ensure that medical services are available to all citizens, regardless of their financial situation or place of residence. The programme covers a wide range of services, including emergency care, primary and specialised healthcare, rehabilitation, and medical assistance for children, pregnant women, new mothers, as well as patients with life-threatening or life-limiting conditions.

The “Affordable Medicines” sticker, indicating the availability of state-funded medications with a doctor’s prescription. Photo source: Poltavshchyna online publication.

Since 2017, Ukraine has rolled out the Affordable Medicines Programme, aimed at improving access to essential medications for individuals with chronic conditions. Under this initiative, patients can receive medications through electronic prescriptions from their doctors, with the option to obtain them either free of charge or with a minimal co-payment.

Bringing education system in line with modern standards

In 2017, Ukraine passed the “Law on Education”, which set the stage for an extensive reform aimed at modernising the country’s education system to make it more flexible, effective, and suited to the demands of the modern world. As part of this reform, a new State Standard for Primary Education was introduced in 2018. From 2017 to 2018, 100 schools in Ukraine trialled the updated standards, and following its success, the system was rolled out across primary schools nationwide. The reform then extended to middle schools but was paused for three years due to the COVID pandemic and the subsequent full-scale war. In April 2023, the reform process resumed.

As part of the education reform, Ukraine introduced the New Ukrainian School (NUS) initiative. This approach focuses on developing students’ competencies, personal qualities, and social interaction, rather than just the mechanical acquisition of knowledge. Today, the principles of NUS are used in the majority of schools across the nation.

The New Ukrainian School

is a principle for structuring the educational process aimed at fostering innovators and citizens who are capable of making responsible decisions and upholding human rights, as well as equipping students with modern professional and technological competencies.

A school in the Semenivka community of Poltava region. Photo: Dmytro Bartosh.

During the school reform, more autonomy was granted to local governments, recognising that they are better placed to understand and respond to the specific needs of schools within their communities. Additionally, middle schools gained greater flexibility to adjust their curricula, teaching methods, and evaluation systems.

The Law of Ukraine “On Education” also provided the legal foundation for the introduction of inclusive education, ensuring that every child, regardless of their abilities or challenges, has the right to appropriate learning conditions within public educational institutions. This has been achieved by implementing specialised teaching programmes, training educators to work with inclusive classes, creating barrier-free school environments, and investing in new equipment.

Photo: Sofiia Soliar

Defying the grip of (pro-) Russian clergy

For centuries, Russia has sought to establish its dominance over Ukrainian lands through a variety of means, including religious influence. One of the key instruments in this effort has been the Ukrainian Orthodox Church of the Moscow Patriarchate (UOC-MP), which, in essence, serves as a branch of the Russian Orthodox Church (ROC) within Ukraine. Many of its priests and supporters have functioned as conduits for Russian propaganda, advancing narratives that downplay Ukrainian identity and promote hostility towards anything perceived as distinctly Ukrainian. This influence became particularly apparent during Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022. Numerous reports emerged of Moscow-aligned priests collaborating with Russian occupiers and actively spreading Russian propaganda.

A pivotal moment in the push for the recognition of the Orthodox Church of Ukraine (OCU) came with the call for its autocephaly, or ecclesiastical independence. In 2016, the Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine passed a resolution appealing to Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew I, urging him to annul the 1686 decree that had unlawfully placed the Kyiv Metropolia — the oldest Christian church in Eastern Europe, founded in the 10th century — under the authority of the Moscow Patriarchate. As part of this appeal, Ukraine sought the granting of autocephaly to the Orthodox Church of Ukraine, which would enable it to function as an independent entity within the Orthodox Christian world. This would allow the OCU to elect its own leader and manage its own affairs without interference from Moscow.

In December 2018, Metropolitan Epiphanius was elected Metropolitan of Kyiv and all Ukraine, taking the helm of the Orthodox Church of Ukraine (OCU). On 6 January 2019, in a grand ceremony in Istanbul, Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew signed the Tomos (decree – ed.) granting autocephaly to the Orthodox Church of Ukraine. This momentous decision set off a wave of church communities across Ukrainian cities and villages shifting from the so-called Mos

cow Patriarchate to the OCU. The Orthodox Church of Ukraine emphasised that this transition was voluntary, leaving it to the parishioners of each community to choose whether to remain with the Russian church or join the OCU. Since February 2020, 539 parish communities and two cathedrals have come under Ukrainian control. As of February 2022, a further 214 religious communities have chosen to join the OCU, and the movement continues to this day.

The Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople

is the spiritual leader and foremost authority in the Orthodox world, possessing honorary power over the Orthodox churches without exercising direct control over them. His responsibilities include fostering unity among the Orthodox churches, representing Orthodoxy on the international stage, and mediating inter-church disputes.

Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew I signs the tomos granting autocephaly to the Orthodox Church in Ukraine. Photo source: President’s Administration.

Furthermore, numerous legal breaches by the so-called Moscow Patriarchate after 2022 led Volodymyr Zelensky to enact the decision of the National Security and Defence Council of Ukraine, titled “On Certain Aspects of the Activities of Religious Organisations in Ukraine”, on 1 December 2022. Law enforcement agencies also began investigating the Ukrainian Orthodox Church of the Moscow Patriarchate (UOC-MP) for its compliance with the terms of its lease on the Kyiv-Pechersk Lavra — one of Ukraine’s most significant Christian landmarks, dating back to the 11th century. This site had essentially fallen under the control of the Russian Orthodox Church (ROC) due to a controversial rental agreement arranged by pro-Russian President Yanukovych in 2013. The appointed head of the monastery, Pavlo Lebed, openly supported and propagated Russia’s invasion and occupation of Ukraine, resulting in personal sanctions being imposed on him in 2023.

In 2023, the rental agreement was cancelled, and the Christian shrine was returned to the control of the Ukrainian state and church. On 7 January 2023, when some Orthodox communities celebrate Christmas according to the Julian calendar, the first Christmas service at the Lavra was held by Epiphanius, the head of the Orthodox Church of Ukraine.

The National Security and Defence Council of Ukraine

is a coordinating body under the President of Ukraine, responsible for the development and implementation of policies in the area of national security and defence.

Metropolitan Epiphanius of the Orthodox Church of Ukraine. Photo source: Wikipedia.

In 2023, the Orthodox Church of Ukraine and the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church implemented a calendar reform and transitioned to new holiday calendars — the Revised Julian and Gregorian, respectively. The old Julian calendar used by the Ukrainian church was 13 days behind the civil calendar, which isolated it from the rest of the Christian world in the observance of major holidays. This move brought Ukrainian believers closer to the international Orthodox community, where the majority of churches had long adopted the new dating system.

Reviving Ukraine’s economy in the decade of war

For Ukraine, the Russian occupation of Crimea and parts of the eastern regions resulted in the loss of key industrial capacities, disruption of supply routes, and significant defence budget expenditures. Another heavy blow came with the sharp decline in the hryvnia exchange rate, which sparked inflation, capital outflows, and a general downturn in the economy. As of November 2013, the Ukrainian Treasury held just $10 million in its bank account – the lowest amount in the past decade. Despite the turbulence of the last ten years, Ukraine continues to work towards economic recovery and has a number of achievements to show for its efforts.

Decoupling from Russia’s natural gas

After President Yanukovych fled and Russia invaded Ukraine, Moscow once again used energy as a weapon to influence Ukrainian politics, exploiting the country’s heavy reliance on Russian gas. In 2014, Gazprom, the Russian company that monopolises gas extraction and supply, inflated prices and eventually completely cut off gas supplies to Ukraine. This move, sanctioned by the Kremlin, pushed Ukraine to the brink of an energy crisis. However, by diversifying its energy sources and forming new partnerships with suppliers like Slovakia and Poland, Ukraine was able to reroute gas that had previously gone from Russia to the EU, helping its economy to withstand the crisis.

A key step towards energy independence came in 2015, when Ukraine’s national energy company, Naftogaz, brought a high-profile case against Gazprom in the Stockholm Arbitration Court. In a landmark ruling, the court found that Gazprom had breached its contractual obligations for gas supply and ordered the company to pay Ukraine $4.53 billion in compensation.

Photo: Yves Herman for Reuters.

In 2016, Ukraine finally renounced all direct procurements of natural gas from Russia. Instead, the country is importing gas from EU countries like Slovakia, Poland and Hungary. Between 2017 and 2018, Ukraine focused on reforming its natural gas market, creating a competitive environment to encourage more suppliers to enter the market.

Navigating new global markets

Russia’s military occupation of parts of Ukraine led to the loss of trade relations with those regions and the severing of ties with the terrorist state, compelling Ukraine to shift its focus towards new upstream and downstream markets.

The signing of the EU Association Agreement in 2014 opened access for Ukraine to the EU market, with its 450 million consumers, making it one of Ukraine’s key partners. However, Ukraine didn’t stop there; it quickly began developing trade relations with countries in Asia, Africa, and the Middle East, seeking new opportunities to export its goods.

Due to the high inflation of the Ukrainian currency in 2014, caused by the Russian invasion, imported goods became more expensive, which stimulated the growth of domestic production. At the same time, the government introduced a number of programmes and incentives to support Ukrainian producers, contributing to the increased competitiveness of Ukrainian products on the global market.

Image source: “Slovo i Dilo” analytical portal

In 2014, Ukraine’s exports totalled $53.9 billion. However, in 2015-2016, due to Russia’s occupation of Crimea and the part of Donechchyna, where the country’s strategically important industries are concentrated, this figure dropped to $38.1 billion and $36.4 billion, respectively. Nevertheless, with successful reforms, exports began to rise again, reaching $47.3 billion in 2018. On the eve of the full-scale invasion, Ukraine primarily exported metals and metal products, plant-based products, as well as machinery, equipment, and mechanisms. Textiles and textile products made up a smaller share of exports.

Boosting the banking system’s resilience

Since 2014, 97 banks have been removed from the Ukrainian market due to capital issues, insufficient liquidity, opaque ownership structures, and other reasons. In response, the government took the initiative and launched a comprehensive reform of the banking system to ensure its stability and protect users’ rights.

One of the key measures was strengthening regulatory policies to enhance the system’s resilience, improve corporate governance in banks, protect depositors’ rights, and combat financial crimes. The new banking law introduced stricter capital requirements, while the National Bank of Ukraine was granted additional tools to oversee financial institutions more effectively.

Photo source: Press service of the National Bank of Ukraine (NBU).

Increasing transparency was another key priority of the reform. The central bank introduced new rules requiring banks to disclose more information about their operations, financial status, and ownership structures. This allowed customers and investors to make more informed decisions and helped improve trust in the banking system.

Creating a transparent land market

Land reform began in 2019 with the goal to establish a transparent land market, attract investment, drive economic growth, and create additional jobs.

The main objective of the reform was to remove the ban on private land ownership, a remnant of the Soviet era when all agricultural land was state-owned. The reform lifted the ban on the sale of agricultural land in two stages: from 2021, land could only be bought by individuals, and from 2024, legal entities would also be allowed to purchase land.

The third stage of the reform aims to open the market to foreign individuals and companies.

Photo: Pavlo Pashko

Culture: fighting for Ukrainian voices to be heard

Just a few years ago, Ukraine was heavily influenced by Russia in the cultural sphere. Russian cultural figures and media products held a near-monopoly across much of the post-Soviet space. This allowed Russia, with its state-controlled media market, to impose its standards, familiar imagery, and political narratives on countries previously under Soviet control. Amidst Russia’s aggressive cultural expansion, Ukrainian institutions, NGOs, and government agencies – often with limited financial and public backing – faced a serious challenge, which they transformed into a drive for rapid development. The full-scale Russian invasion has further fuelled the growth of Ukraine’s independent cultural sector, where the need to assert, nurture, and safeguard Ukrainian culture has become as crucial as reclaiming occupied territories and defending borders.

Cover of the TNMK music video “History of Ukraine in 5 Minutes”.

Strengthening institutions for global engagement

To strengthen Ukraine’s global presence, the government established the Ukrainian Institute in 2017. This organisation focuses on promoting cultural and scientific cooperation internationally, raising awareness of Ukraine, and introducing foreign audiences to its context. Between 2019 and 2024, the Institute conducted research on global perceptions of Ukraine and Ukrainian culture, as well as an in-depth study on how Ukrainian history is represented in foreign textbooks and media. This research has laid the groundwork for Ukraine’s future international efforts, marking the country’s first targeted policy for developing its global image since gaining independence in 1991.

First programmes and projects of the Ukrainian Institute. Screenshot from the official website of the organisation.

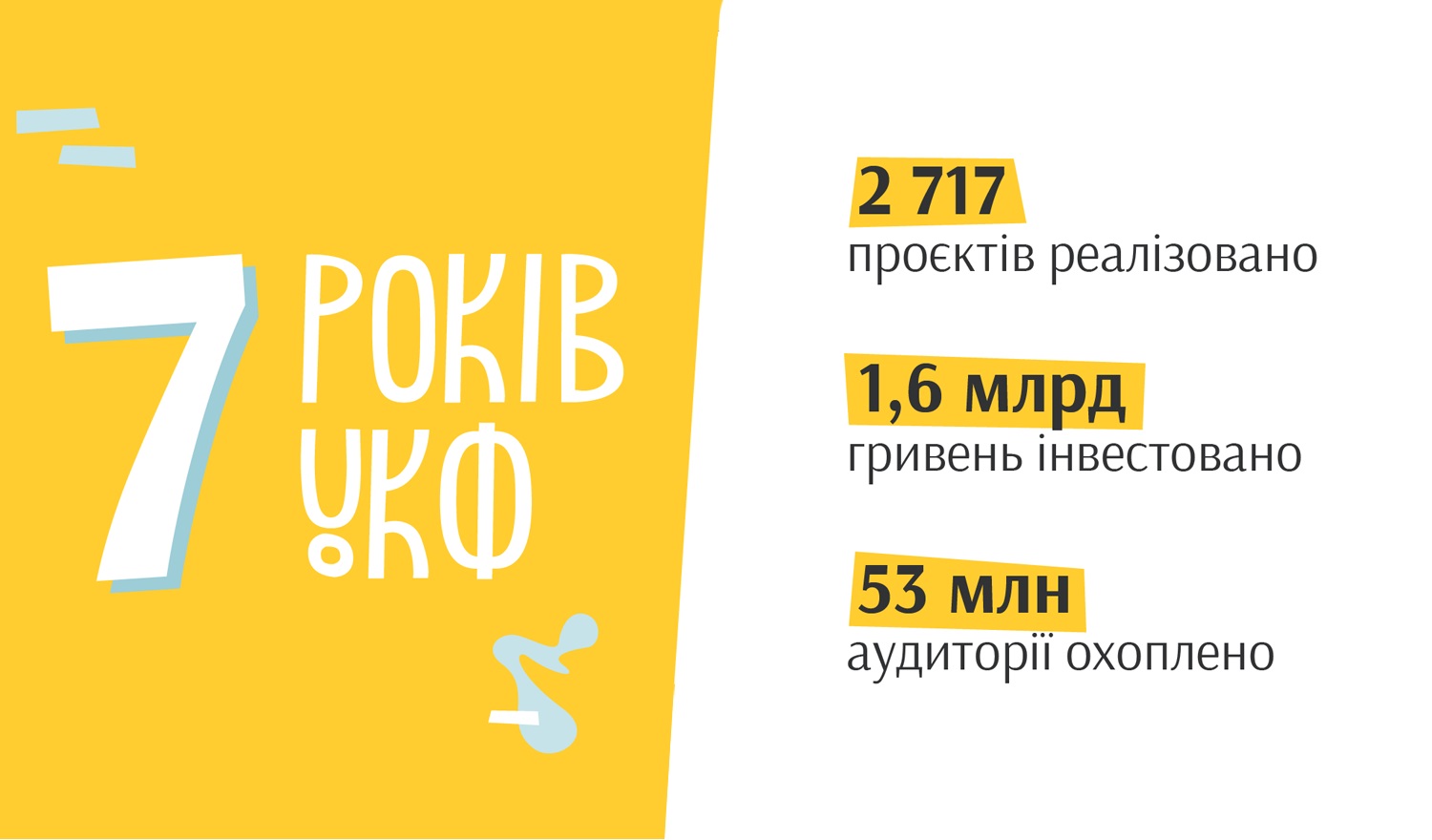

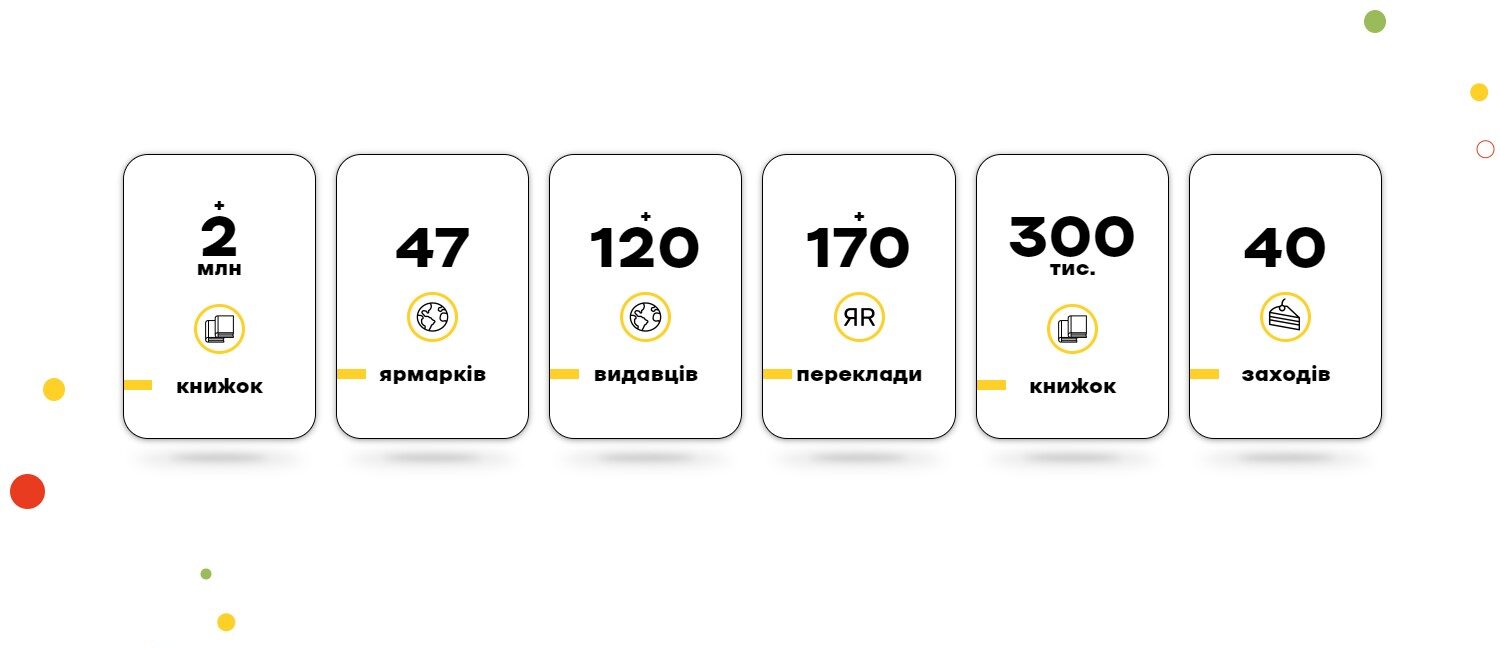

In the same year, the Ukrainian Cultural Foundation (UCF) was established under the Ministry of Culture of Ukraine. The Foundation is renowned for offering grants to support cultural projects, including literature, music, theatre, film, as well as initiatives related to folk art, visual arts, and architecture. It also plays a key role in promoting cultural values, fostering a rediscovery of ethnic identity among Ukrainians, and running cultural and awareness-raising campaigns aimed at elevating cultural standards within society.

Screenshot from the official website of the Ukrainian Cultural Foundation (UCF).

In 2016, Ukraine also set up the Ukrainian Book Institute, which plays a key role in reviving the popularity of Ukrainian-language literature and supporting local publishers. The Institute develops and implements strategies to grow the Ukrainian book market, supports publishers, encourages the publication of new books, and broadens the range of themes and genres in domestic literature. It also promotes translations of Ukrainian literature into foreign languages, helping to raise awareness of Ukraine and its culture internationally — an effort that has become especially crucial since the full-scale invasion.

Screenshot from the official website of the Ukrainian Institute of Culture (UIC).

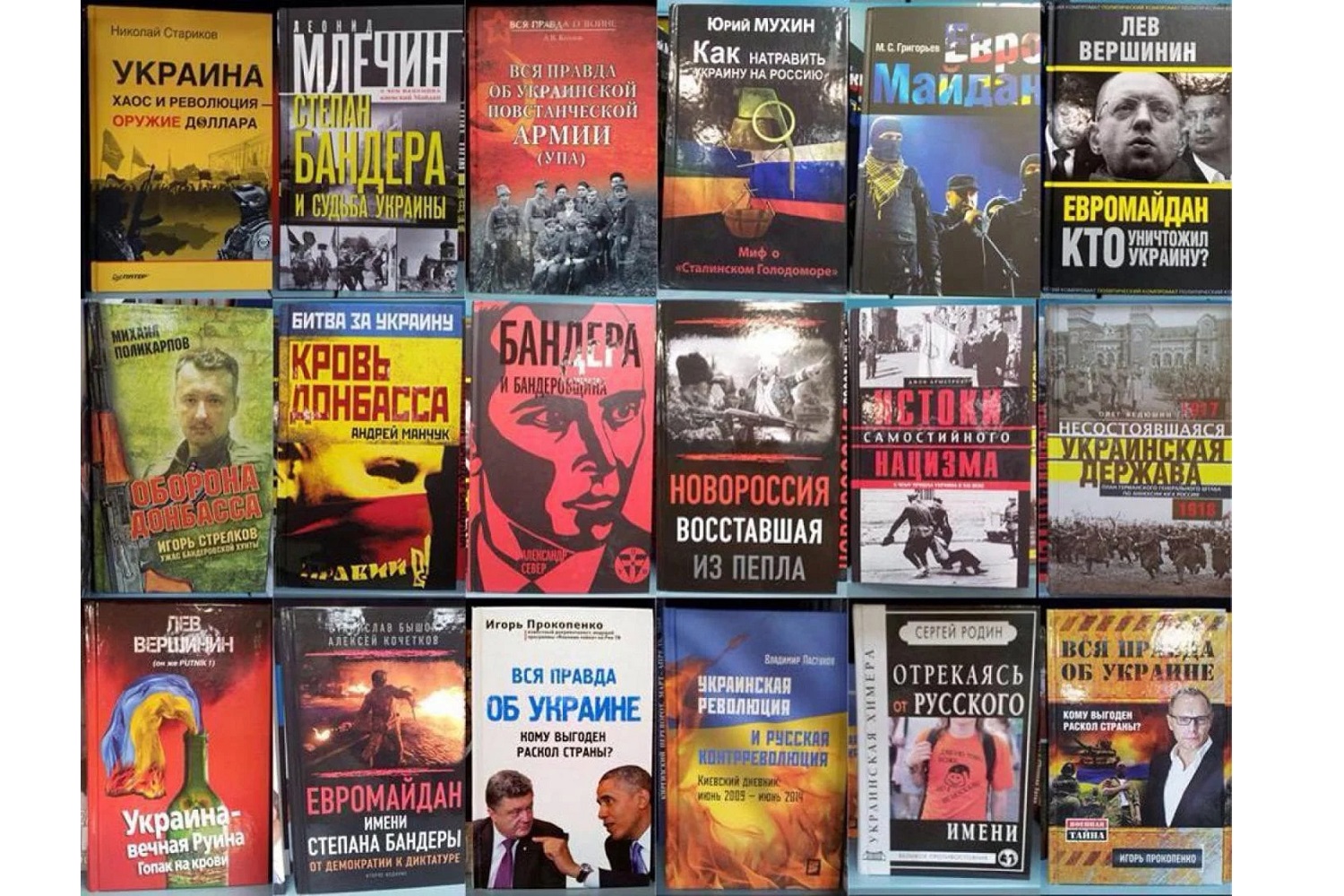

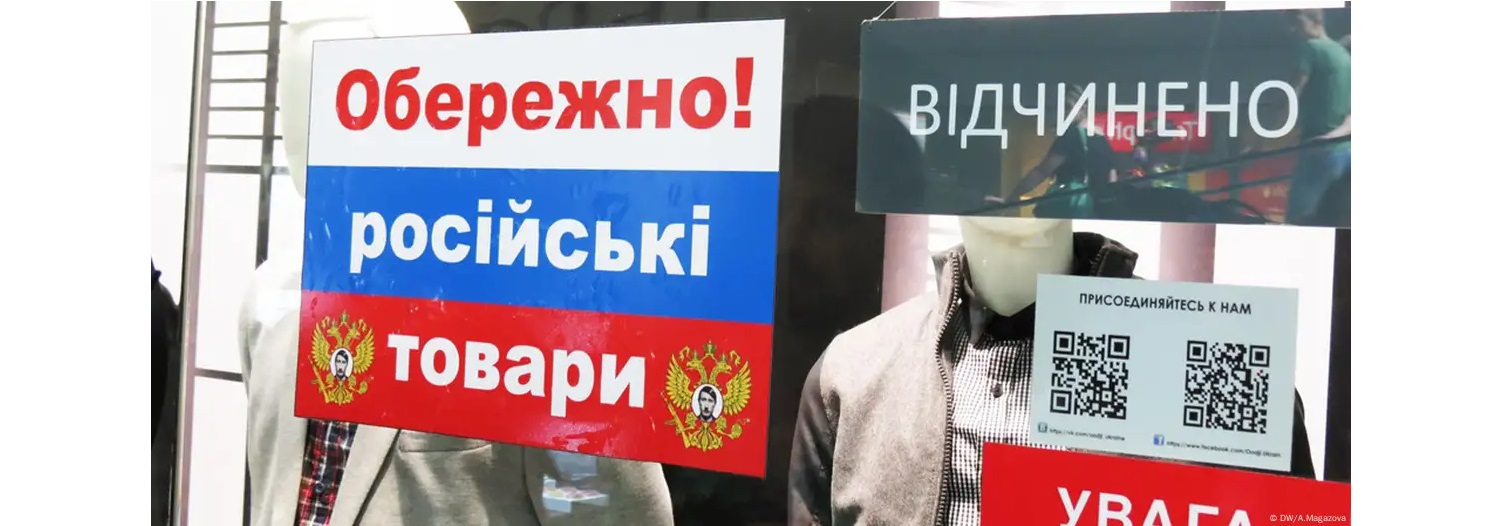

Revitalising Ukrainian book industry

Cheap, mass-market Russian books were a powerful tool of Russian influence on Ukrainian readers. The need to counter this form of information warfare became even more pressing after Russia’s invasion in 2014. In 2016, Ukraine introduced its first legal restrictions on the import of Russian books, initially focusing on those with anti-Ukrainian content. These publications were actively produced and distributed by Russia to spread propaganda, justify its actions, and assimilate populations in occupied territories. However, right up until the full-scale war, Russian books still held a significant share of the Ukrainian market.

Russian-language literature. Photo source: gwaramedia.com.

In June 2022, Ukrainian parliament passed a bill banning the import of all books printed in Russia, Belarus, and the Ukrainian territories currently under Russian occupation, as well as books by authors who were (or have been at any time since 1991) citizens of Russia, with a few exceptions.

Industry leaders hope that the new legislation will create more space on bookstore shelves for books by Ukrainian publishers. However, the law still has some blind spots, particularly with electronic content, and will require additional resolutions and regulations to be fully effective. As a result, the true impact of these changes, or lack thereof, will only become clear in the future.

Photo: Anastasia Magazova for DW.

Boycotting Russian propaganda films

In 2015, Ukrainian lawmakers banned the screening of films and TV series produced in the Russian Federation after 1991. This move was a response to the overwhelming presence of Russian content in Ukraine, as well as the genuine security threat posed by Russia’s use of film to spread anti-Ukrainian propaganda and historical distortions worldwide. Since 2014, the State Film Agency of Ukraine (Derzhkino) has been removing Russian-produced content from cinemas and television. By 2018, 780 films and TV series from Russia, which contained propagandist anti-Ukrainian messages, had been banned.

Actors from the Russian propaganda TV series. Photo source: “Toronto Television” Facebook page.

The main reasons for the ban were the threat posed by the actors in these films to Ukraine’s national security, as well as the promotion of methods and imagery associated with Russia’s and the USSR’s punitive institutions, which distorted facts and spread falsified historical narratives.

A new wave of opposition to Russian cinema emerged following Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine. The Ukrainian Film Academy called for an international boycott of works by Russian directors, urging that their films be excluded from screenings, festivals, and competitions. This call was driven by the ongoing use of art, particularly cinema, by Russia to justify its crimes and spread distorted historical narratives.

For instance, in September 2024, the Venice Film Festival premiered Russians at War, directed by Russian filmmaker Anastasia Trofimova. The film sparked controversy due to Trofimova’s past work for the Russian state media conglomerate RT, which has been banned in several EU countries and the UK for spreading disinformation and hate speech. She had also filmed in Ukrainian territories under occupation, violating Ukraine’s border laws. The Ukrainian community strongly protested the film’s international screenings, as it portrayed the Russian occupation of Ukraine in an unduly positive light, downplaying Russia’s war crimes.

Mitigating the impact of Russification

Although the Ukrainian Constitution established Ukrainian as the state language in 1996, in practice, it remained sidelined in many areas of public life due to Soviet-era Russification policies. However, in recent years, Ukrainian has been steadily regaining ground in both public and private spheres, driven by legislative changes and a growing desire among Ukrainians to break free from the Russian influence. This shift has been particularly pronounced since Russia’s full-scale invasion.

One of the measures used to promote the Ukrainian language in the media has been the introduction of language quotas. This initiative aimed to support domestic producers, who often struggle to compete with foreign content, particularly from Russia. Following the introduction of the relevant law in 2016, a certain percentage of radio and television programming was required to feature content in Ukrainian. As of 1 January 2024, the mandatory minimum for Ukrainian-language content on radio and television broadcasters was set at 90%.

In 2019, Ukrainian parliament passed the law “On Ensuring the Functioning of the Ukrainian Language as the State Language” to address the legacy of forced Russification. The law ensures the right to receive services in Ukrainian across government institutions, local self-government bodies, education, healthcare, media, culture, commerce, services, and advertising.

Restricting Russian music in public

For similar reasons, in 2022, the Ukrainian parliament passed a law banning the public performance of Russian music. The law prohibits the playing of Russian songs at concerts, clubs, and other venues, as well as their broadcast on radio and television, the airing of Russian music videos and the use of Russian song recordings at public events.

Collage by the Centre for Countering Disinformation under the National Security and Defence Council. Image source: Ukrainian Radio.

However, there are some exceptions to the ban, particularly for musical works created before 1991 or those that are not directly associated with propaganda or the promotion of aggression.

Reclaiming Ukrainian artists from Russia

Russian aggression has prompted Ukrainians to actively decolonise the global perception of Ukraine and Russia. As part of this effort, Ukrainians are striving for the recognition of artists as Ukrainian, rather than Russian. For example, art historian Oksana Semenik launched a social media campaign encouraging museums around the world to reassess the national identities of artists who have often been mislabelled as Russian.

The painting “Red Sunset on the Dnipro” by Arkhip Kuindzhi, 1905. It belongs to the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. A sketch of the painting from the Kuindzhi Museum in Mariupol was lost after the city was captured by Russian forces in 2022.

In early 2023, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York began reclassifying the works of artists Ilya Repin, Ivan Aivazovsky, and Arkhip Kuindzhi, recognising them as Ukrainian artists. Previously, the museum had referred to them as Russian artists or artists celebrated in both Russia and Ukraine. In addition, the museum changed the title of a piece by French impressionist Edgar Degas. What was once known as Russian Dancers is now titled Ukrainian Dancers. In March 2023, the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam began presenting Kazimir Malevich as a Ukrainian artist.

The work “The Woodcutter” by Kazimir Malevich from the collection of the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam, 1912-1913.

Ukraine’s path towards territorial integrity, institutional development, and a progressive future is still ongoing. Many of the reforms mentioned have proven effective and have been enshrined in legislation. Others will demonstrate their impact, along with areas needing further refinement, in the future. Despite imperfect results at times, mistakes, and external factors hindering progress, the past decade has been a period of significant change for Ukraine, showcasing the resilience and determination of Ukrainian society.