Mariia Hurbich

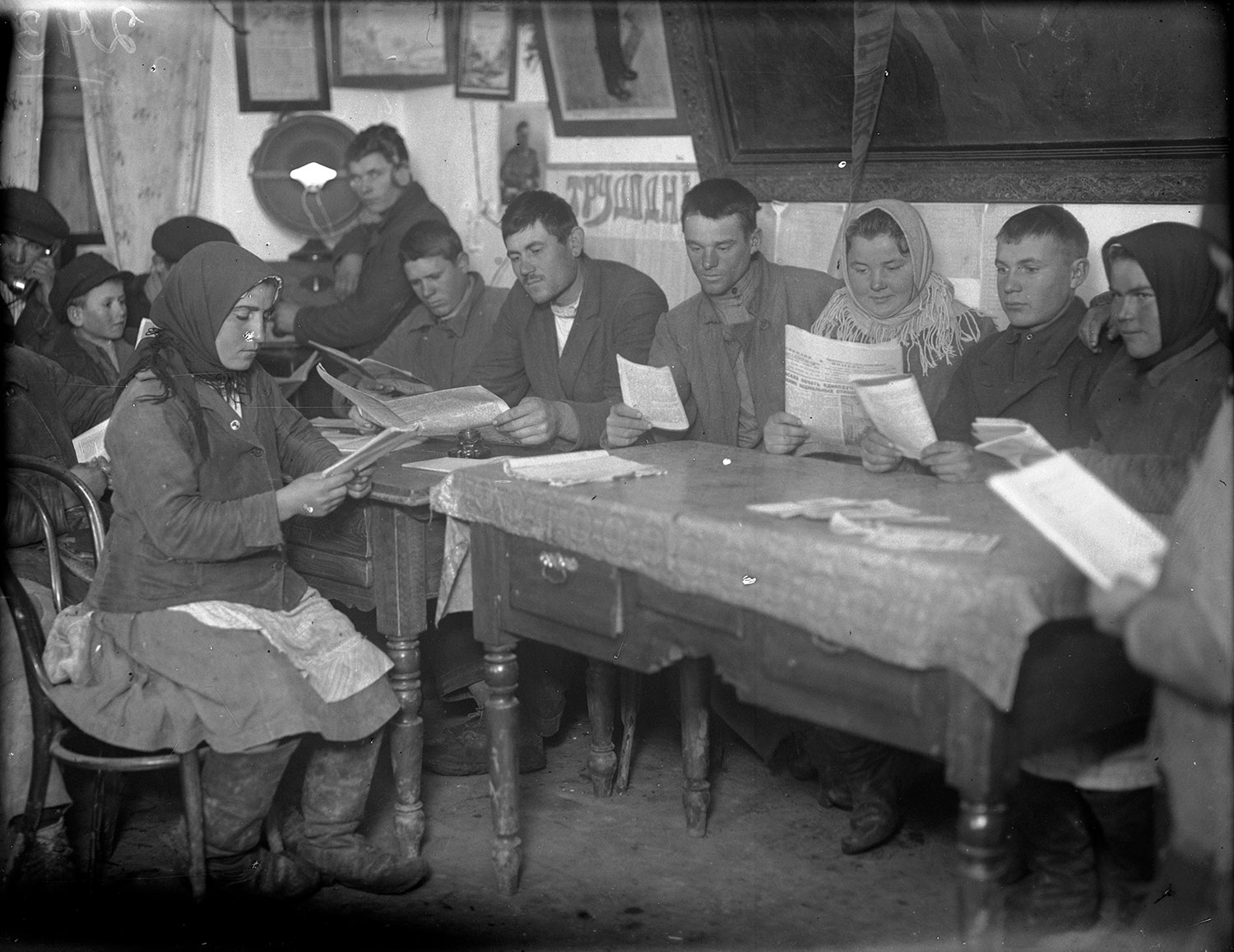

When the Holodomor (famine genocide in Ukraine) started, Mariia was twelve. Not only did she survive the genocide of the Ukrainian nation together with her family, but she also helped a neighbour boy survive. They met by chance years later. And although what had been happening all over Ukraine in 1932–1933 resembles the time when some regions of the Donbas were captured in 2014 (the Russian occupation in the East of Ukraine — ed.) in that the poorest volunteered or were forced to become “activists” and had to take the last piece of bread from their neighbours, still people such as Mariia were secretly helping each other survive.

Tetiana Krotova

When the Holodomor (famine genocide in Ukraine) occured, Tetiana’s family lived in the hamlet of Shevchenko, situated near Kropyvnytsky city. The head of the local collective farm (“kolhosp”) became a criminal to the Soviet government and secretly gave food to the villagers — the same food that was taken from them and left to rot before. There were no traitors in the village who cooperated with the authorities, so no one died during the Holodomor.

Fedir Zadiereiev

When the Holodomor (famine genocide in Ukraine) broke out in the village of Kobylianka, Fedir’s parents had to travel on foot 100 kilometres to Belarus to bring potato peels from their relatives. Fedir’s grandmother sneaked potatoes in her boots, and Fedir cooked borshch from nettle and plantain leaves for his younger siblings. Thereby they managed to survive. Fedir recalls that prior to collectivisation (a policy adopted by the Soviet government to transform traditional agriculture from private property to collective state-controlled ownership — tr.), people in the village could lend money to each other for as long as half a year, though during the Holodomor he had to steal from his neighbours to survive.

Nadiia Korolova

Nadiia was born in the village of Ivankivtsi in Podillia region. When the Holodomor broke out, she was 10 years old. Podillia was among the first regions to start rioting against mass compulsory collectivisation (making villagers forcefully join collective farms, “kolhosps” — ed.) and the closing of churches in 1929. Outraged by the regime’s actions, Ukrainian villagers chased out the local officials and activists from their villages and took control over the district centres. In 1932 the opposition of the rural population reached threatening levels, and the Soviet regime sent military units to suppress the riots. The clashes lasted for days.

Marfa Kovalenko

Marfa was six when the Holodomor began. All those terrifying events of the Ukrainian genocide were engraved in her memory, despite her very young age. The family’s only cow was confiscated; they were promised to get a cow back sometime later, but her father made it clear: he would not take any other cow besides his own, not an animal seized from some other family because of him. Thanks to the mutual support in the village, Marfa’s family managed to survive.

Valentyn Kuzan, photographer

Valentyn Kuzan, photographer