This episode of Ukraine Through the Eyes of Others features Mark Laity, NATO’s former leading expert on strategic communications and retired communications director at SHAPE, the alliance’s main military headquarters. With over twenty years of experience as a BBC journalist, he is also the founder of the Stratcom Academy.

In this interview, Mr. Laity provides insights into the strategic and historical contexts of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, emphasising the dangers of appeasement and exploring the strategic narratives underpinning modern conflicts.

The conversation also delves into the importance of military history in understanding ongoing wars, the challenges of securing defence spending in democracies, and the strategic narratives the Kremlin uses to justify its aggression.

We’re recording this interview at the Royal Air Force Club in London. Why is it important to you that we’re doing it here?

I think it’s symbolic of my nation’s history, which has a lot of military in it. The Royal Air Force (RAF) was formed in our greatest times of struggle (the RAF was founded in 1918 – ed.), but also for me it has a special meaning because my father was in the Royal Air Force in the Second World War. He was in Bomber Command, flying as a rear gunner in Lancasters, which suffered enormous losses during the Second World War, with 55,000 of the 125,000 who served dying.

Overall, 75,000 people were killed, wounded, or taken prisoner. That shows the required cost of any major war. That was an existential conflict for my country, and my father played his part as a very young man. His first combat mission was shortly after he turned twenty. I think it illustrates what is needed in Ukraine — and any other country fighting for survival — just as my father did.

What was the conscription age back then in Britain?

It was eighteen. My grandfather also served in the Second World War, he was in his late thirties at the beginning of the war and was also called up. He served in the Royal Navy and received medals for gallantry. The Second World War and the First World War involved conscription of all our young people, from eighteen to upwards. In some nations, it was twenty-one. But when you’re in an existential conflict, it’s all in. If you’re in a prolonged, attritional conflict, like the Second World War was and like Ukraine is now, it’s inevitable that you will need a lot of people. It’s not about getting everyone to the front line but ensuring you have rotation, training, leave, rest. Not everyone needs to be called up at once because what you’ve got is a situation where you cannot predict the end of a war. So, conscription — speaking as a former BBC defence correspondent and a NATO official with over two decades of experience — is a standard method for sustaining significant conflicts over a long period. It inevitably involves people from the age of twenty and upwards, with an increasing number of women being called upon as well.

Could you take us through the late 1930s and explain how the British appeasement policy unfolded, and where it ultimately led?

It occurred for a number of reasons. First of all, in Britain they didn’t want to go to war again. There was a mood of, if you like, peace at a considerable price. The Prime Minister at the time (Neville Chamberlain – ed.) bought into that. The British defences, along with France, which was our main ally, were also very weak. As a result, when faced with a rising aggressive power like Germany, there was a desire to appease them in order to avoid war. We reassured ourselves that Hitler didn’t intend to be what we now know he was, believing that if we just conceded or struck a deal, it would all come to an end. But the issue was that every time we gave Hitler something, he saw it as a weakness and wanted more. It was far from appeasing him to stop – it encouraged him to go on. And what then happened is that every time we gave him something, he got stronger, and at the same time, we were not rearming very quickly, so our relative weakness looked even worse. When Hitler ended up taking Czechoslovakia, he gained a large army and a highly capable defence industry, which enormously strengthened the Nazis. And that meant we were in a very vulnerable position to fight him effectively. The whole appeasement policy made things worse. If we had moved in harder on Hitler at the beginning when he was still weak, things might have been different.

Russia was always relatively strong, but the lesson here is that we appeased Putin in Georgia in 2008. Even in 2014, we thought there was a middle ground or a way out. What we didn’t do was read Putin right. Putin would not stop unless there were significant powers and forces against him. Hitler also wasn’t going to stop unless we could force him to stop. History is never the same but it does rhyme. Appeasement only works if the person you’re trying to appease is reasonable and Putin is not. He wasn’t reasonable back in the early 2000s and yet we kept thinking we could make a deal with this man.

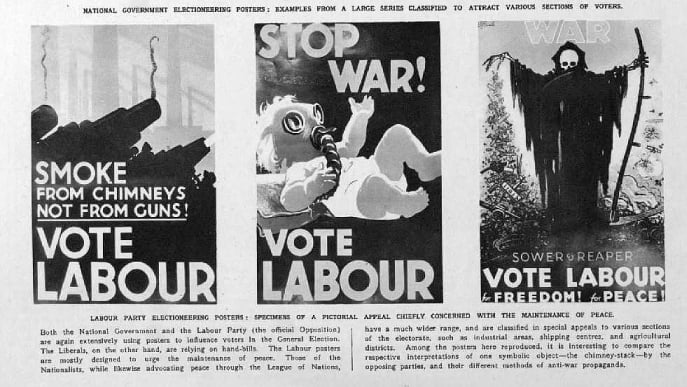

In 1935, during the British general election, the Labour Party used the slogan “Armament means war; vote for Labour.” They opposed dictatorship but refused to back increased arms spending. Ninety years on, it’s still often said that there are no votes in defence.

I think there are very few votes in defence in most major democracies. If you ask people what they want their money spent on, they want it spent on education, health, etc. Who can blame them? But the first duty of any government is to provide security. It’s easy to take the populist route — there are no votes in defence, so let’s not talk about it or allocate funding. But that’s a mistake, a serious mistake. The current Labour Party is very different from the one then. Still, the comparison is valid because people often think you are somehow warmongering if you spend money on defence. The essence of NATO and Western nations lies in deterrence, which is built on willpower and capability. Communication is also crucial — they must understand that you possess both the will and the means. We have failed in this, and the consequences are evident, particularly in Russia, which believed we were weak. The Russian perception of our weakness encouraged them to continue doing what they were doing. When the second invasion of Ukraine happened (the full-scale invasion – ed.) we reacted very well. If only we had shown that will and capability in 2015, would 2022 have occurred? And we will now spend a lot of money on defence. If you look back to the Second World War, Britain was still a very powerful country in 1939. By 1945, however, we were a bankrupt nation. Why? Because we had to spend so much on defence. Ultimately, it would have been cheaper to build up our forces in the 1930s and not wait until 1939 or 1940, when we had to spend all our money and resources to fight an existential threat. So it’s easy to argue for spending on schools instead of defence, but as a democracy, we must defend our values, which requires deterrence and weapons.

Warmongering

Warlike rhetoric or actions that encourage the idea of war, often by advocating for military aggression, spreading hostile attitudes, or pushing for war as a solution to international issues.

Do you think the West has finally woken up?

Yes, it has; whether it’s woken up enough is another matter. After the Cold War, we had the so-called peace dividend, and defence downsizing was significant. As a result, our ability to rebuild from where we are now has had a slow start. And that’s the problem: we now have far too few armaments and ammunition factories.So you’re seeing many nations upping the defence spending, but the amount of money we need to invest is almost an emergency crisis. The Russians have a completely false narrative about why they’re doing what they’re doing. This is an aggressive attack on a neighbouring country with zero justification. People often fool themselves, thinking that peace is always the answer. Indeed, peace might always be a way in the end, but you’ve got to get to a fair peace. The most peaceful places in a country are graveyards, but no one wants to live in them. So “warmongers” suggest that there’s an aggressive intent on part of Ukraine and its allies, but the facts show that the aggression came from Russia; Russia invaded Ukraine – not vice versa. Peace should not come at any price – you want the right kind of peace, one that allows you the freedom to vote, make your own decisions, receive an education, and have children – and that requires effort. In this situation, false warmongering allegations against Ukraine is an inadequate and glib response that will make Putin very happy, but no one else.

What are the main strategic narratives that the Kremlin uses to justify its military aggression or undermine the support for Ukraine?

There’s a series of them, often to different targets. The main one, which they use externally, is that Ukraine was a threat to them and the war was fueled by NATO expansion, which is simply untrue. To their people, they are saying that this is the return of Russia as a great power, while externally they claim to be a victim. They also have a narrative for the more neutral nations, such as in Africa, which aims to portray Russia as an anti-imperialist power in contrast to allegedly imperialist NATO states. This has some traction because, of course, in Africa, it was countries like Britain and France which were the colonisers. Although we are no longer colonisers – we’ve moved on – Russia remains an incredibly imperial power, but it mainly colonised the countries around it. History shows that Russia is not just a coloniser or imperial power; in many ways, it still is, unlike the former Western colonial powers. So, Russia is still an imperialist power, but it’s not as visible so it plays this card in places like Africa and other regions.

Putin often quotes Catherine the Great and says that “the only way to defend Russian borders is to expand them.” How do you think the Ukrainian government could use this in strategic communications?

There clearly needs to be more realisation among some of the more neutral nations and faraway nations that Putin’s idols are Catherine the Great and Peter the Great, who were expansionists. So, when he talks about what Russia wants, they should pay attention to what he says internally to his own people and in his speeches instead of focusing on his claims about NATO’s alleged expansionism.

Catherine the Great (1729–1796)

was a Russian empress who expanded Russian control over Ukraine, integrating it more closely with Russia. Her rule diminished Ukrainian autonomy and increased Russian dominance.I think that it needs to be an essential thing to use their history against them, not by making it up but by demonstrating what Russia says and why NATO nations, the new ones in Eastern Europe and the Baltics, want to be part of NATO. If you look at the nations that were part of the former Soviet Union – Moldova, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Uzbekistan, and Kazakhstan – almost all of them, without exception, face significant problems. Georgia has breakaway states, disillusionment, disinformation, and Russian influence. These are poor, unstable countries, and Russia is interfering with all of them. Then, you have the three former Soviet nations that are in NATO: Lithuania, Estonia, and Latvia. They’re in the EU, they’re stable, and two of them have large Russian minorities. Are they being oppressed? No. Now, look at the ones that aren’t: Ukraine, Moldova, Georgia, Armenia. The reason these countries want to join NATO is because they fear Russia. And Russia has no reason to be afraid of them.

Peter the Great (1672–1725)

was a Russian czar whose rule marked the expansion of Russian influence into Ukrainian lands. His efforts to modernise Russia included asserting control over Ukraine, further integrating it into the Russian Empire and diminishing Ukrainian autonomy. His policies laid the groundwork for increased Russian dominance in the region.Why was NATO created, and has its purpose changed over time? What is NATO’s value today, in your opinion?

NATO was formed in 1949 as a response to the growing threat from Russia, recognised by the future NATO nations. Almost all countries rapidly disarmed themselves after the Second World War, but Russia (the USSR – ed.) did not. Stalin maintained a large military presence, and there were a series of struggles in various countries, including Greece, Czechoslovakia, and what became the Soviet bloc. In these regions, Russian influence was deeply malign. They were using communist parties in nations like France and Italy to try to undermine them. There was a sense of enormous threat and a very obvious tank-based threat from the Soviet Union. Fortunately, at that time, the United States had a group of people who recognised that they needed to stay involved in Europe for the safety of what we would call the Western world. That’s still very important because if you look at the member states of NATO, virtually none of them could protect themselves against a major attack. At the end of the Cold War, for a while we thought it was a kind of the end of history. Now, we have recognised that great power competition has not ended – in fact, it is intensifying – and as individual nations, we are too small. Therefore, we have almost returned to where it all began: as a basic deterrence organisation with enough power to defend our borders.

If, as the Kremlin claims, the Russian invasion of Ukraine is all about NATO enlargement, then why are Russians abducting and deporting Ukrainian children and citizens deep into Russia?

It’s how they exert control, the Russian people are very ambiguous in their views. Russians often see themselves as victims, and everybody is against them. At the same time, they view Russia as a mighty power that everyone should respect. On the one hand, everybody hates us, and we’re victims, while, on the other hand, there is mighty Russia with our incredible culture, fantastic language, and the “Russian World” (a Russian colonial narrative which promotes the annexation of states neighbouring Russia based on their affiliation with the Russian language, culture, and shared history – ed.). The reality is that Russia has always used its language, culture, and its people to try and control its surrounding nations. One of the things they’ve done over the centuries is mass deportations. Russians went into an area, put their people in and took the local people out. This happened during the Tsarist times, but it was supercharged by Stalin. You saw massive deportations in Moldova, Georgia, Crimea, the Baltics. Deportation is not just a bad thing to do, but it’s a means of policy. It’s important that people understand this and that it is used as a strategic communication message. What Putin is doing is following through an imperialist policy, which is centuries old but is also very clearly a copy of what happened under Stalin.That shows who the expansionist is and who the victim is. The deportation policy is not just cruel, wrong, and a war crime – it must be understood as part of Russia’s broader attempt to change the very nature of Ukraine.

What is the Russian vision of war, and specifically, of information warfare?

Russia is almost proud of its ability to take enormous casualties. If you look at the First World War under the Tsars, the Second World War under Stalin, and now the invasion of Ukraine, you see that Russians are willing to take casualties at a level that, frankly, no Western nation would or should. Beyond that, the Russians, like many nations, have a vision of political warfare. Social media, disinformation, key individuals, corruption, all of these come together into information confrontation, supercharged by AI and the growth of social media. We know the problem, but the weaponization of disinformation, the ability to flood the zone with bots, false information, the ability to polarise societies is a big weapon, which is a significant problem for Western societies to cope with.

We often talk about resisting and countering disinformation as if we are always trying to catch up with the enemy. How could Western messaging be more proactive and less reactionary?

If a nation or an opponent is prepared to lie, then trying to deal with them tactically will always fail. If you take, for example, the shooting down of the Malaysian airliner over Ukraine or the attempted killing of Russian defectors in Britain, every time the truth came out, the Russians kept putting forward new narratives. They spread 5 to 20 different stories, mainly to confuse the situation. This is a deliberate tactic: if you can’t make people believe you, you make them distrust everyone.

Malaysia Airlines Flight MH17

was shot down over the east of Ukraine on 17 July, 2014, by a missile fired by Russian forces, killing all 298 people on boardHannah Arendt, a notable theorist of totalitarianism, highlighted that the people most susceptible to totalitarian control are confused and don’t know the difference between true and false. One of the things the Russians have done is flood the zone with confusing stories. So when I advise people I always say: don’t obsess about disinformation. Trust is based on many things, not just your credibility but also your story and who you are. We need strong narratives, and if you have a strong narrative, you are very resistant against disinformation. If you know what you believe, if you understand what’s going on, then when somebody gives you a false story, you wash it away.

So, the answer is solid and clear narratives, demonstrated by what you do and say. That’s not easy, but it’s the only thing that will work when somebody is just spouting out lies at a rate that you can’t answer.

Hannah Arendt (1906–1975)

was a German-American political scientist known for her analysis of totalitarianism and the nature of evil. Her key works include "The Origins of Totalitarianism" and "The Human Condition," which explore political power and public life. Her concept of the "banality of evil" is widely influential.You were there at the project’s origins, bringing strategic communications to the heart of NATO. What challenges did you face back then, and how can ethical yet effective influence campaigns be carried out in defence?

When I joined NATO, we tended to have a naive and limited attitude toward using public information. We had good public affairs officers, we had people who did psychological operations, but nothing linked together. In particular, strategic communications weren’t important in the military; it was all about the weapons. In the 1990s and early 2000s it became clear that information is a weapon. Groups like the Taliban, Al-Qaeda, and the Russians, used information as a way of shaping the battlefield. We were way behind the curve, lacking people, training, and thoughtful planning. And so we tried to change this. The leadership came on board, and we’ve advanced from a basic stance to a solid, doctrinal approach to strategic communications. We have now gotten NATO into a position where strategic communication is very important. In their use of political warfare, the Russians had a much better instinctive understanding of the use of information in what you would call a hybrid environment. Because that’s what was happening in the Cold War, which was a battle for belief, influence among other things. We were not bad, but we forgot all the lessons at the end of the Cold War, and the Russians continued. The Chinese are also pretty good at it. It’s very important to understand that until the fighting starts full-on, your primary weapon is strategic communication.

In terms of ethics, I was a BBC journalist, and the BBC prides itself on its impartiality. But one thing I learned there is that you cannot be neutral between good and evil. You can’t have a situation where you say, “well, Winston Churchill says the Germans are bad, now let’s go to Hitler and see what he thinks.” Balance is not finding something in the middle but understanding what’s happening and putting that over to your audiences. Impartiality is about commitment to being fair. As a strategic communicator, I am not neutral. However, I worked for democratic institutions and therefore I had to live up to specific values. NATO’s strategic communication policy has its number one principle: values. Therefore, it is entirely fair and completely ethical to try to influence others, as long as it aligns with these values.

You spent 22 years in journalism, including 11 years as the BBC defence correspondent, before becoming a special advisor to the Secretary General of NATO. At what point in your career did you become both professionally and personally invested in Ukraine?

I had a certain amount to do with the Baltics when they broke free from Russia or the Soviet Union. I also had a lot to do with the Balkans, but I had a limited amount of knowledge about Ukraine before the first Russian invasion. My interest came after 2014 when the Russian aggression became evident and the Ukrainians fought back so clearly. I went to Ukraine a lot, met Ukrainians, and saw a nation changing itself. I saw many people who understood values often better than people who were more complacent about them. Nothing will make you value what you’ve got better than the apparent threat of losing it. And the Ukrainians know that. You are fighting for us. I’m aware that if Ukraine loses, Europe loses, and Western democracies lose. The biggest loser would be Ukraine, potentially occupied with an authoritarian nation. But the world will also lose by signalling to aggressors that they can act without consequences with the West not strong enough to stop them. This could encourage China to move on Taiwan. Unless we do what’s necessary for Ukraine, it would show a lack of commitment. I am also professionally invested because I’m a British citizen, and I don’t want my country to fall short by not doing enough for yours.

What’s your opinion on the direction the war is taking?

Unfortunately, it’s going to be a war of attrition — it’s already in that phase. I don’t see Putin backing down in any way, and there’s no peace in sight. He has demanded territory he doesn’t control, the demilitarisation of the Ukrainian army, and neutrality that would leave the nation vulnerable to him taking full control. He is offering nothing but capitulation to Russian control, and that’s existential for Ukraine. Ukraine cannot give up, because if it does, it has essentially capitulated, and it has lost the war. There’s no middle ground here. At the moment, I don’t see any clear pathway to peace. In terms of the war’s progress, I don’t see a decisive military advantage for either side. The balance might slightly favour Russia, but not enough for them to take control, and it could quickly be reversed. Sadly, the reality is that Ukraine has done an outstanding job, but it will have to keep doing so.

What would Ukraine’s victory mean to you personally?

It would be a massive win for the West as well. It’s an opportunity for us to reset the world to the way we want it to be. For Ukraine’s victory, peace would mean getting you into the EU first and establishing peace so that you can become a significant European power, which is what it should be. Ukraine is big enough, it has the talent, and should be an important player in Europe. That’s what I want to see in the end. It will take time, but the Ukrainian people can look ahead. It may take a while, but Ukraine will get there and become a force in Europe, in a positive way.

Ukraine won’t change, and I don’t see Putin changing either. Militarily, the Russians may have a slight advantage at the moment, but not by much — certainly not enough to win the war. Ukraine doesn’t have that advantage either. So, what we’re looking at, sadly, is a reasonably long war, in which Ukrainians will have to grit their teeth, join the military, serve, and endure hardship.