In the temporarily occupied territories of Ukraine, Russia aims to erase the national identity of the local population. For the occupiers, it is crucial that people abandon their own national identity in favour of Russia, as this strengthens their hold on the conquered lands. However, Ukrainians in the temporarily occupied territories refuse to accept the “Russian world” and are determined to help the Ukrainian defence forces liberate these areas as soon as possible. One of these resistance groups is known as Zla Mavka (Evil Mavka).

The “Russian world”

An ideology of state-endorsed Russian imperialism that promotes the annexation of neighbouring states based on their affiliation with the Russian language, culture, and shared history.Zla Mavka is an all-women resistance movement that uses non-violent methods to fight against the occupiers. It started in Melitopol (a city in southeastern Ukraine that was occupied by Russia in the first days of the full-scale invasion) in early 2023, when open resistance to the Russians became nearly impossible. The members – called mavkas — operate anonymously and don’t know each other. They put up posters and leaflets, spread accurate information to counter Russian propaganda, and do whatever they can to keep the occupiers on edge, never letting them feel secure.

Only the three co-founders of the movement know one another. For their safety, we cannot reveal their real names; instead, we’ll call them Mavka One, Mavka Two, and Mavka Three. The women shared how the resistance movement began as a joke, how they can easily spot Russians trying to infiltrate it, and what they miss the most while living under occupation.

Mavka

A forest spirit in Ukrainian folklore, depicted as a beautiful, ethereal young woman who lures people into the woods. Mavkas are often presented as the souls of unmarried girls who died tragically.

From a kitchen joke to a resistance movement

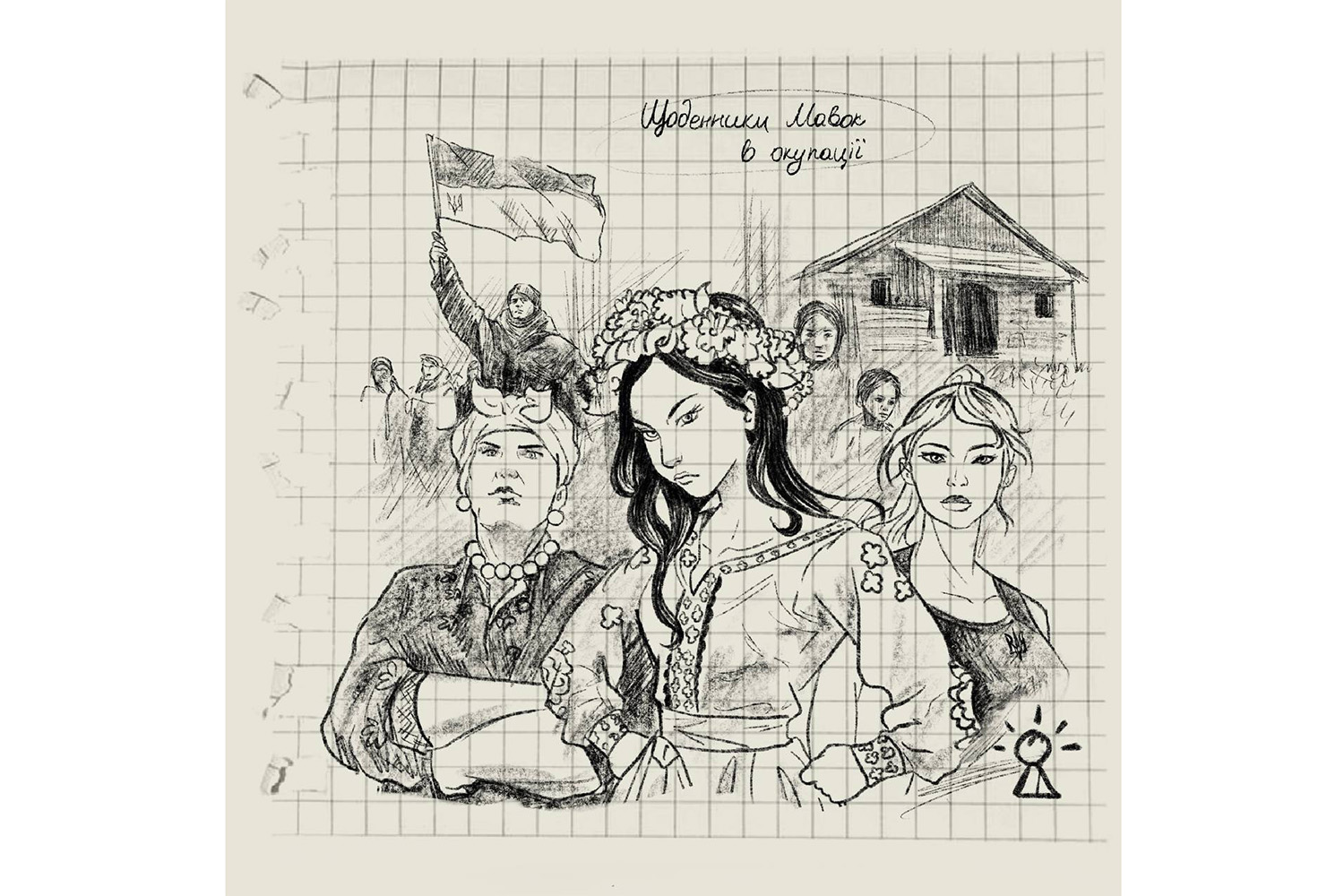

Zla Mavka operates in occupied cities and towns both online via a chatbot-enhanced Telegram* channel and on the ground. The movement’s logo features three women, representing the founders: one in traditional Ukrainian clothing, another holding a rolling pin, and the third in modern attire. These images are deliberate — they subvert stereotypical depictions of women, turning them into symbols of female strength.

*

While Ukraїner considers Telegram an unsafe platform, it remains one of the few available communication channels in the temporarily occupied territories.The co-founders say there’s no heroic story behind the creation of the movement. The main catalyst was the presence of occupiers and Russian flags in their hometown. Each of them had already supported anti-Russia activists in Melitopol before launching their initiative. But as reprisals persisted and resistance went underground, they decided to show the Russians what defiance from Ukrainian women could look like, Mavka One explains.

“[We wanted] to show that our women are brave and strong, and we will never play nice with them here. Plus, at that time (referring to 2022-2023 — ed.), they were behaving very arrogantly toward our girls, and resistance from women really got under their skin.”

Photo source: “Zla Mavka” telegram channel.

Mavka Three recalls that the movement began as a joke in the kitchen, with one of them saying, “Why don’t we start an organisation to resist the Russian occupation?” The idea came from a sense of helplessness and anger.

“At first, it was a kind of resistance out of sheer principle. When you know that the circumstances are stronger, but you still push back.”

The women opted for a non-violent form of resistance to annoy the Russian occupiers and remind them that they weren’t welcome in Melitopol. When they started planning their activities, the Mavkas never imagined it would evolve into a large women’s movement. For safety reasons, everything began within a small circle of friends. Mavka One recalls that their first project involved distributing leaflets, which also helped them connect with like-minded people.

“We came up with drawings and messages that would really annoy [the occupiers] and spread them where they would definitely be seen. Then we decided to set up a Telegram channel to show people what we were doing and what was happening here. That’s when things really took off. Women and girls from other occupied cities started reaching out, asking us to send them our leaflets so they could do the same. We didn’t expect to hear from so many. That’s when we realised it was time to get organised and take this seriously, to establish rules, safety measures, and everything else.”

Now, the movement has followers in various Russian-occupied regions of Ukraine, stretching from Donechchyna to Crimea. The Mavkas developed a Telegram bot to allow participants to communicate easily with the leaders and receive tasks. This ensures anonymous and secure communication, which, according to Mavka Three, is a top priority.

“We never ask for real names or any information that could reveal someone’s identity. Communication only happens through secure messaging apps. Plus, we constantly remind everyone about cybersecurity: clearing chats, not storing any sensitive information, and so on.”

Mavka Two adds that people in the occupied territories have learned to be cautious, as the occupiers sometimes carry out searches, checking mobile phones particularly thoroughly. That’s why the Mavkas advise their activists to use two devices if possible. If that’s not feasible, they recommend not storing anything on the device that the occupiers could use as evidence of underground activities.

This atmosphere of anonymity could potentially benefit the Russians and their security services who might seek to infiltrate the movement and expose its participants. However, according to Mavka One, they can usually identify these infiltrators quite easily.

“It’s often quite amusing. I don’t know how they were trained, but ‘comrade major’ looks ridiculous trying to pass as a girl! Our rules are set up so that the most he can get from us is a task. So let him go and draw a Ukrainian flag!”

What truly hurts the Mavkas is seeing traitors among long-time friends or even family members, says Mavka Two.

“It’s like knowing someone for half your life, only to realise they’d betray you for some perks from the occupiers.”

Resistance with a sense of humour

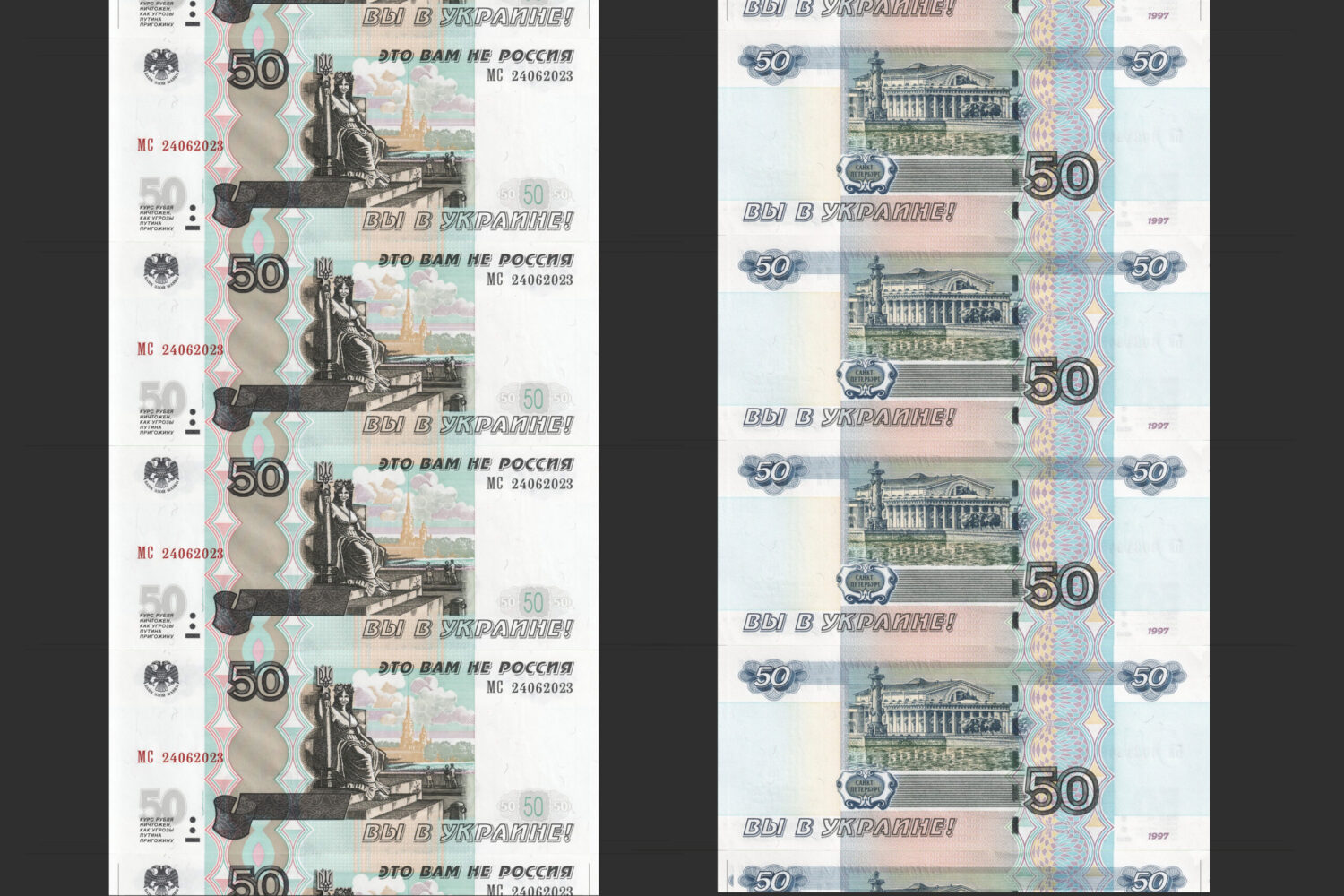

The activists take pride in all their actions, but one of their favourites is “Mavka Money”, an initiative in which they redesigned Russian ruble banknotes by adding images of Mavkas. These banknotes circulated in Melitopol, Berdyansk, Tokmak, Kakhovka, Simferopol, Sevastopol, and Yalta (Russian-occupied cities in the south of Ukraine – ed.). Over time, they were even spotted in the Kuban region of Russia. Mavka Three recalls that they didn’t have to wait long for a reaction from the occupiers.

“The first banknote was amazing. [The Russians] went wild in their channels and in the comments. Watching their reactions was hilarious. The funniest part was that the discussion only escalated when an English newspaper picked it up. Instead of brushing it off as a minor issue, they inadvertently amplified the very idea they were trying to dismiss.”

Mavka's 50-ruble note with the inscription "You are in Ukraine. It's not Russia."

Mavka One recalls that when they successfully released the first “copy” of a ruble banknote in Melitopol, local pro-Russian channels portrayed it as an attempt to undermine the Russian banking system.

“Just imagine! We released copies of their rubles with the slogan that [Russian occupiers] are in Ukraine, and they thought we were the fools! We released a 50-ruble note, and they claimed that such a small denomination couldn’t possibly disrupt their banking system or affect the circulation of the ruble. I read it and couldn’t believe my eyes. Our latest joke at their expense ended up being labelled a serious terrorist act.”

For Mavka Two, her favourite initiative was “Mavka’s Kitchen”. Initially, the women simply distributed posters warning the occupiers to be careful about what they ate or drank. Later, the activists gained access to the kitchen where the Russians dined and added a laxative to their food. They later did the same with homemade alcohol.

“When the occupiers went door-to-door asking for moonshine or food, I thought, why not? I know how to cook, and if a bit of laxative ends up in the food, it happens. As for moonshine, that’s a risky business. Maybe I missed something along the way. That’s how the idea for ‘Mavka’s Kitchen’ came about. Everyone loves it.”

Now, the occupiers in Melitopol often hesitate to eat food they aren’t sure about, even if it’s just fresh fruit or vegetables.

“Mavka’s Kitchen”. Photo source: “Zla Mavka” telegram channel.

“Mavka’s Kitchen”. Photo source: “Zla Mavka” telegram channel.

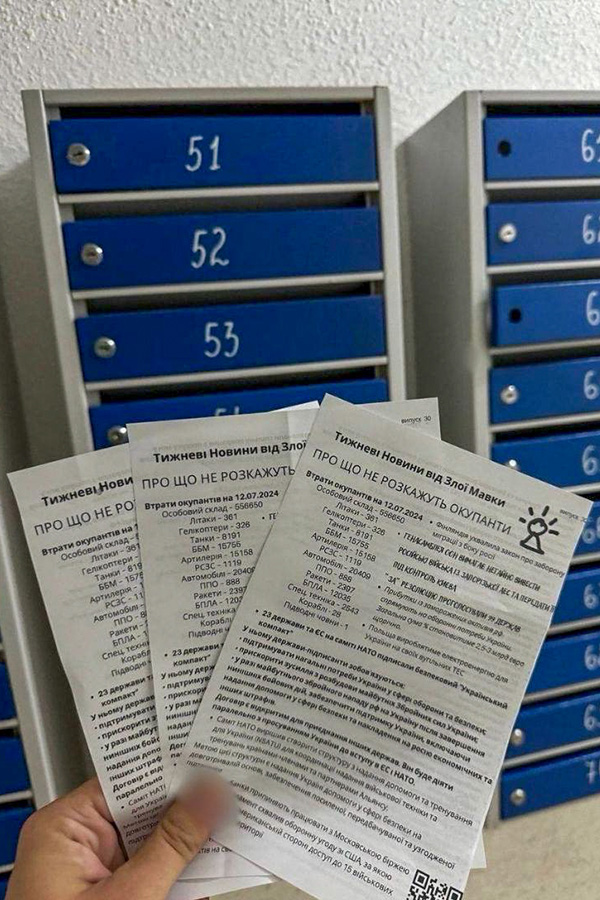

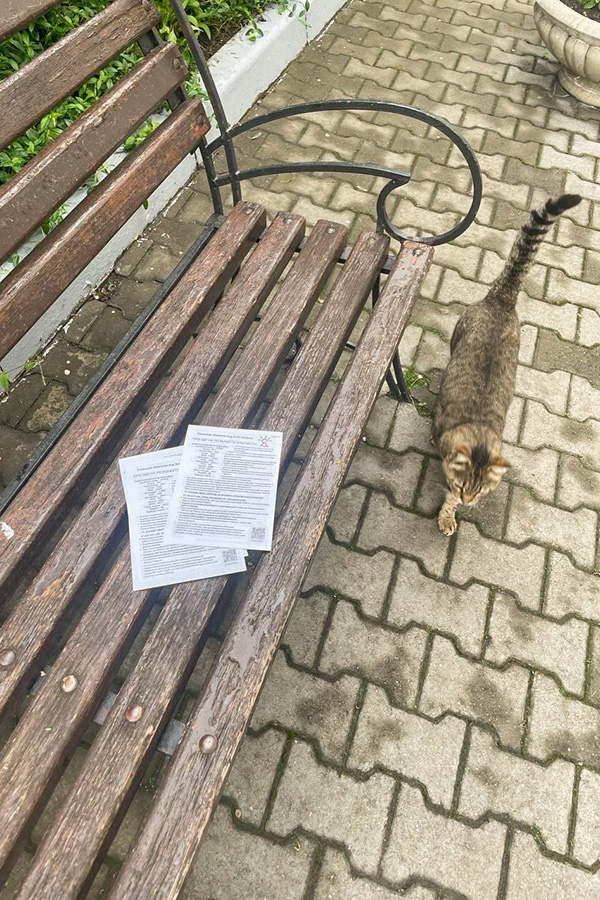

Another key aspect of Zla Mavka’s activism is producing a weekly newspaper. Accessing accurate information in occupied territories is challenging, Mavka One explains, discussing the motivation behind launching this publication.

“Finding news is easy these days, but not for everyone in occupied areas. For example, the older generation, who might not know how to bypass blocks or use VPN, or simply don’t want to risk searching for Ukrainian channels, are left relying on their televisions. And we all know what that means — they’re only exposed to Russian propaganda.”

The idea to create a newspaper struck Mavka Two during a visit to a friend outside the city. She noticed that her acquaintances were watching Russian news on TV and that they thought that was enough, choosing not to look for any alternative sources of information.

Zla Mavka’s weekly newspaper. Photo source: “Zla Mavka” telegram channel.

Zla Mavka’s weekly newspaper. Photo source: “Zla Mavka” telegram channel.

Now, the Zla Mavka team puts together a weekly summary of key events happening in Ukraine. They distribute printed copies of the newspaper through mailboxes, leave them by front doors, and drop them in parks, encouraging readers to pass them along to others after reading. The electronic version of the newspaper can also be downloaded from their Telegram bot. Mavka Three recalls instances where people downloaded the newspaper and shared it further via messaging apps. Such actions also bolster the movement:

“Even sharing one newspaper, poster, or sticker is already a small personal victory for someone who manages to do it.”

The Zla Mavka movement operates without sponsors or funding and typically doesn’t require large budgets. Anyone who wants to join the movement can contribute; if they have a printer at home, they can print posters, newspapers, stickers, or even counterfeit banknotes for their next act. What truly matters for the movement’s functioning is strong morale, Mavka One explains.

“We need motivation, inspiration, and faith in victory above all else. Material concerns aren’t our main focus here. Sure, money is needed, but it’s not the be-all and end-all. What we really need are more eyes and ears. For people to keep resisting, they need to feel that their efforts aren’t in vain. We often notice that the number of activists rises whenever good news comes from Ukraine or the battlefield. People feel inspired and ready to take action again. But it works the other way too — everyone’s reading online, and it’s all too easy to lose motivation.”

That’s why Mavkas consider supporting other women in the occupied territories another vital aspect of their work. They remind these women that they have someone to turn to, to talk to, and that others share their thoughts and views. Mavka One makes an effort to keep participants from dwelling on their sadness, while Mavka Three adds that even simple conversations often make a real difference.

“This isn’t about persuading anyone to think differently but about providing friendly, mutual psychological support. It’s like chatting with a friend in the evening. That’s the vibe of our Telegram channel – everything is infused with sarcasm and humour.”

Mavka Two mentions that the three of them often respond to messages from participants together.

“We’re friends. Even though I’m older than many, they come to me for advice or just to cry quietly when things get tough. Many girls from different cities reach out to me for advice or just to discuss life under occupation. Then [the Mavkas] come to me, we sit down together, and we start responding to everyone. It’s like an anonymous women’s club. I genuinely hope to meet some of them after liberation; we’ve never seen each other, but it already feels like we’re friends.”

The Mavkas also noticed how vital it is for women in the occupied territories to feel supported by those in Ukraine or abroad.

“I remember how thrilled they were when they saw photos of women from different countries painting our symbol on their arms! It was truly amazing,” Mavka One recalls. “Lots of Mavkas wrote to us back then, but one message particularly resonated with me: ‘I don’t know how you did it, but thank you. It meant the world to me to see that we haven’t been forgotten, that people are proud of us and keep fighting for us — that gave me the strength to keep fighting.’”

Zla Mavka's supporters across the world. Photo source: “Zla Mavka” telegram channel.

What’s truly disheartening, however, is the criticism suggesting Zla Mavka’s actions are insufficient, and the participants could be trying harder. The founders find it strange to read such comments, particularly from those who aren’t in Ukraine. Conducting open resistance in occupied territories is incredibly challenging, as the Russians have installed surveillance cameras throughout the streets and plan to set up facial recognition technology soon. The occupiers check people on the streets, carry out searches, and do everything they can to make life difficult for both activists and ordinary citizens, explains Mavka One.

“You have to consider a lot of factors before even putting up that poster. And that’s precisely why it hurts when fellow Ukrainians write that we’re doing some pointless nonsense. You flinch at every sound, every shadow, or even from your own fear. Sometimes, this fear is valid: someone might peek out from a window (and there are plenty of informers around), a car drives past, or something else happens… Each time you think, ‘This is it, I’m going to get caught…’ But then, as if you’re in a fog, you quickly do what you need to and escape. And even when you’re safe, you don’t feel safe. What if someone saw you? What if there was a camera you missed? What if they find you…?”

Life under occupation imposes severe restrictions, making basic survival the greatest challenge. The Mavkas observe that the longer the occupation drags on, the harder it becomes for people to resist and maintain hope. With restrictions on information, struggles to meet basic needs, and psychological pressure from the Russians, Mavka Two feels that such conditions compel people to better understand and appreciate what they had before.

“We took for granted many things that we now feel deeply. It’s the freedom to speak the language you want and to express your thoughts openly. It might sound odd, but I even miss the Ukrainian products that I used to enjoy. Unfortunately, as time goes by, people start to adapt to this way of life. That’s probably the most frightening part.”

For the Mavkas, this means one thing: becoming more resourceful, exploring new ways of resistance while staying anonymous, and keeping morale high.

Zla Mavka's diaries of occupation. Photo source: “Zla Mavka” telegram channel.

Fight and you will prevail

The co-founders make all decisions about Zla Mavka’s activities, but only if everyone is on board. Other participants who join take responsibility for their own safety and the risks involved. Mavka Three explains that the safety rules are always consistent.

“The orcs (Russians — ed.) will arrest you for a Mavka sticker as easily as for a newspaper. Burning a Russian flag is probably the riskiest act. We carefully discuss who will do it, whether there are any cameras and the best time to carry it out. Plus, we never share the results immediately [online] to avoid tipping off the enemy.”

For this reason, the Mavkas try to only document their activities through their own resources, such as a website section called “Mavka Diaries”, their Telegram channel, or partnerships with journalists. They try to avoid keeping any personal records, as Mavka Three explains. “That would be like building a criminal case against yourself in a Russian court.”

There’s also the psychological pressure. For the Mavkas, it’s mainly the presence of the enemy occupying their homeland. They also endure online harassment, receiving offensive comments and mass sexist threats in their Telegram channel or on enemy platforms. The Russians often try to hack Zla Mavka’s social media accounts, setting up clones of their chatbots or fake movement accounts to communicate with local residents. At the same time, as Mavka One points out, the occupiers try to downplay the movement’s existence.

“They belittle our actions in their public forums, calling us rats or insisting that we don’t exist at all. But seriously, guys, why are you sending the Youth Army to cover up our graffiti if that’s the case? The worst thing for them is to admit that we are here. Because then they have to admit that they don’t have the support they claim in their propaganda. That’s our main mission: we show the world that we exist and that people here are waiting for Ukraine!”

The Youth Army

A Russian paramilitary organisation for minors that was established by Russia’s Defence Ministry in 2016. The organisation has faced widespread criticism for militarising Ukrainian children in occupied territories.These obstacles do not diminish the Zla Mavkas’ determination to continue their resistance. The women want to make it clear to the Russians that they haven’t accepted the occupation. As Mavka Two puts it, “Sometimes you wonder if it’s all in vain and they really came to stay. But then you tell yourself, ‘Do your job, and our guys will come.’”

One of Mavkas in Melitopol. Photo source: “Zla Mavka” telegram channel.

In addition to community support, humour — often dark — helps the Mavkas carry on with their activities. While stories about their actions may seem amusing in hindsight, they can involve real risks for the participants at the time. Mavka One recalls a girl who went to hang up leaflets in Crimea. She found a spot near a fence to pull them out discreetly, but then she encountered someone else.

“Just as she pulled them out, an old man appeared behind her. She hid the leaflets and waited for him to pass. But instead, he approached her and said, ‘I see, salt!’ [slang for drugs in Ukrainian — ed.). At first, she thought he suspected she was looking for something hidden, but she quickly realised it was serious. He grabbed her — she barely managed to hide the leaflets — and dragged her towards a house, saying he was going to interrogate her about where she bought drugs. The girl managed to escape, and everything ended well. But there was both laughter and danger involved. The old man could have called the police, and they would have found our leaflets, but thankfully, that didn’t happen.”

"Let's clean up the Russian garbage." Photo source: “Zla Mavka” telegram channel.

Even though the Mavkas carefully prepare for each outing, unexpected situations still arise. It’s a relief when a nearby stranger shares pro-Ukrainian views, as happened with Mavka One.

“The scariest moment [I’ve had] so far was burning Russian flags. I didn’t want to do it in a yard; I wanted to do it right there, where the occupiers could see it, not just on Telegram. When it works out, it’s an unmatched feeling! Sometimes, I have to return to the same spot five times to get it done because something gets in the way. But one situation caught me off guard… During the process, a woman appeared. She saw me, and I saw her; we both just stood there, shocked, staring at each other. Then she smiled and said, ‘Hurry up; there’s a patrol car nearby. You better go down Street X.’ I was stunned but quickly ran off with a smile — they’re OUR people!”

Support from the outside world also boosts the women’s determination, Mavka Three shares. “When foreign journalists reach out to us, we feel like we’re doing something right. Not long ago, I came across a post by a Ukrainian soldier who noticed our work and wrote a thank-you note… It brought me to tears… We’re the ones who are grateful! We will do everything we can as long as it makes a difference…”

Everyday rituals and small comforts also offer solace to the Mavkas. For Mavka Three, it’s about planning and tidying up. Mavka Two finds comfort in items that remind her of life before the full-scale war. Mavka One sometimes feels like her connection to a peaceful life is lost, but she holds on to a special talisman that inspires her.

“This is a photo of my grandfather… He’s from Donechchyna, wearing traditional embroidered clothing, handsome and intelligent… When I feel drained, I imagine what he would say about all of this… And then, when I picture it, I get up and do what needs to be done.”

Overall, Ukrainian culture and symbols help the activists maintain morale, even though preserving traditions in occupied conditions is incredibly challenging. The Mavkas mention that they only practise these traditions in family settings, never in public. For Easter, they decorated pysanky, and in winter, they celebrated St. Nicholas Day and Christmas. They do this quietly, as open resistance has disappeared in the occupied territories, unlike in the early days of the Russian invasion. The occupiers suppress any acts of resistance. However, Mavka Two points out that certain habits among people still persist.

Pysanky

Traditional Ukrainian Easter eggs decorated with intricate designs using a wax-resist technique.“I saw people in the hospital speaking to the staff in Ukrainian. They didn’t even realise they shouldn’t be doing that since it’s their mother tongue. You should have seen how irritated the doctors from Russia were. They even threatened those people. So, we experienced a gentle Ukrainisation, and now we’re facing forced Russification.”

Mavka's money with the inscriptions "Russian banks have no place here." (top) "Crimea is Ukraine." (bottom). Photo source: “Zla Mavka” telegram channel.

Mavka's money. Photo source: “Zla Mavka” telegram channel.

The Russian occupiers are generally enraged by any reference to Ukrainian culture. The Mavkas note that the Russians have come to impose their ways of life while erasing local customs and laws. This includes the letters “ї” and “є” (unique Ukrainian letters absent in the Russian Cyrillic alphabet – ed.), which frankly frighten the invaders, as well as the overall Ukrainian history and identity. Zla Mavka serves as a reminder to the Russians that they are merely temporary visitors and that they will never fully suppress the Ukrainian spirit.

“You have more power in your hands than you think,” Mavka One emphasises. “You realise that every action you take matters; it’s inspiring. Ukrainians are amazing, really! And Ukrainian women are cooler than Marvel superheroes.”

In their struggle, the Mavkas have seen not only the strengths of Ukrainians but also their striking differences from the Russians. Mavka Three points out that Ukrainians don’t need what is foreign, only what is their own. Mavka One sees no similarities between the two nations.

“It’s not that we are brothers; we aren’t even distant relatives. They lack innate culture, taste, critical thinking, and internal freedom. They have no sense of self, dignity, or will – and so much more. They have no truth.”

Mavka Two adds that what sets Ukrainians apart is their sense of internal freedom.

“It’s an integral part of us. [Russians] don’t grasp that they can change things; they follow like sheep to the slaughter. We have always been accustomed to changing the hetman when we don’t like them.”

Hetman

A historical title for a supreme leader in Ukraine, originally referring to the commander of the Kozak army and later the head of the Ukrainian Kozak state that existed in the 17th and 18th centuries.Zla Mavka continues its efforts in the occupied territories against all odds, vowing to do so until de-occupation. Specifically, the women aim to show the world that Ukrainian resistance exists and that people in the occupied territories are not welcoming Russia and refuse to live under its rule.

“We’re trying to tell the world what is really happening here, to speak about Russia’s crimes. We publish diaries from the occupied territories so that the world knows the truth — that we continue to fight for justice here and ask them to keep fighting for us.”

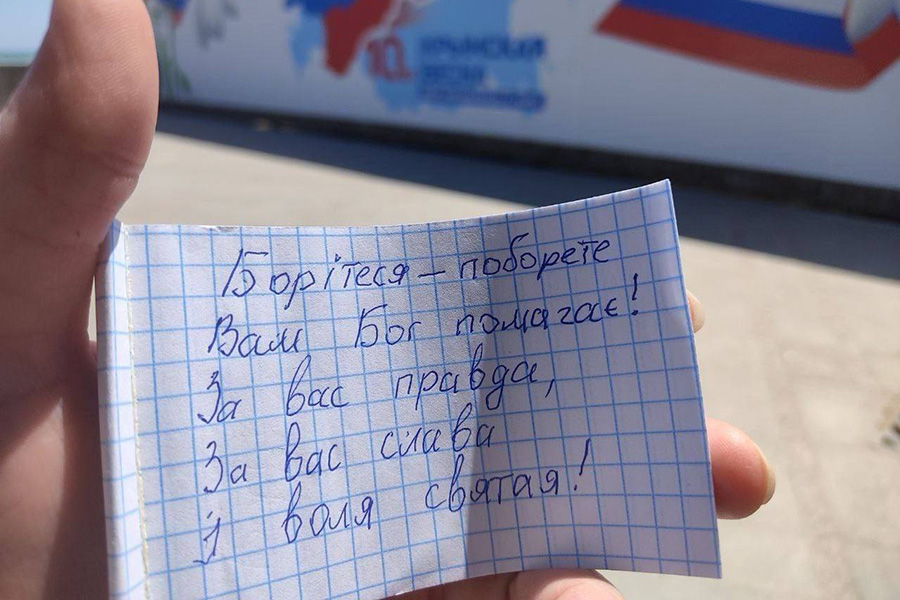

‘Keep fighting — you are sure to win! God helps you in your fight! For fame and freedom march with you, And right is on your side!’ (English translation by John Weir). Photo source: “Zla Mavka” telegram channel.

*

The inspirational lines from Taras Shevchenko's anti-imperialist poem The Caucasus that are widely known among Ukrainians.

The Mavkas urge people to remember that people living under occupation want to return to Ukraine and call on them to have faith in their capacity to make this happen. They encourage other underground groups and movements to stay strong, be cautious, and believe in Ukraine’s victory.

“The best advice we received long ago was, ‘Fight and you will prevail,’” says Mavka One. “Each person chooses their path, doing what they can and what they believe is necessary. Most importantly, we all share one goal — Ukraine!”

Mavka Two emphasises that the scariest thing is living under occupation, so Ukrainians must keep going. “Let those Russian monsters see every day that they can’t break us and that we will never be Russians.”