Lyre art was once widespread in Ukraine, from the 16th century to the 1930s when Soviet officials ordered to “clean up” cities and villages of Ukrainian musicians. History contains allegations of Soviet officials organizing a conference for 300 Ukrainian Kobzars, where all of them were trapped and executed. There is no documented evidence of this execution taking place, as many records from that period were lost or destroyed, but the ancient Kobzar tradition suffered a severe blow.

Ukrainian Kobzars

Blind musicians and bards who played lyres and other stringed instruments, passing along ancient songs and legends.Almost 100 years later, Hordii Starukh, a sculptor from Lviv, decided to dedicate his life to reviving and continuing the tradition and set a goal to learn how to make a lyre and manufacture 300 of them.

In 2009 Hordii made his first lyre. He has since created dozens of them, and his shipping destinations now reach as far as South Korea.

An Artistic Legacy

A sculptor by education and musician at heart, Lviv native Hordii Starukh can play various musical instruments and used to be a member of the band Joryj Kłoc. He has managed to combine his main passions — music and sculpture, crafting lyres for almost a decade. He learned this craft from scratch and worked it up to an unprecedented standard, looking for ways to improve his technique with every new instrument he makes, in order to get the best sound. He makes each part of his instruments himself, including the keys and body. He attaches a unique signature spiral crank, unlike most European cranks which are S-shaped. Each of his lyres is unique and has its own set of nuances in the sound.

Since early childhood, Hordii has always been influenced by the creative people in his life. His grandfather, Emmanuil Mysko, was a sculptor, famous across the globe and furthermore, co-founder of the National Academy of Arts in Ukraine. The family’s involvement in the arts and their tradition of sculpting was continued by Hordii’s uncles as well as his father, who is also a writer, painter and musician.

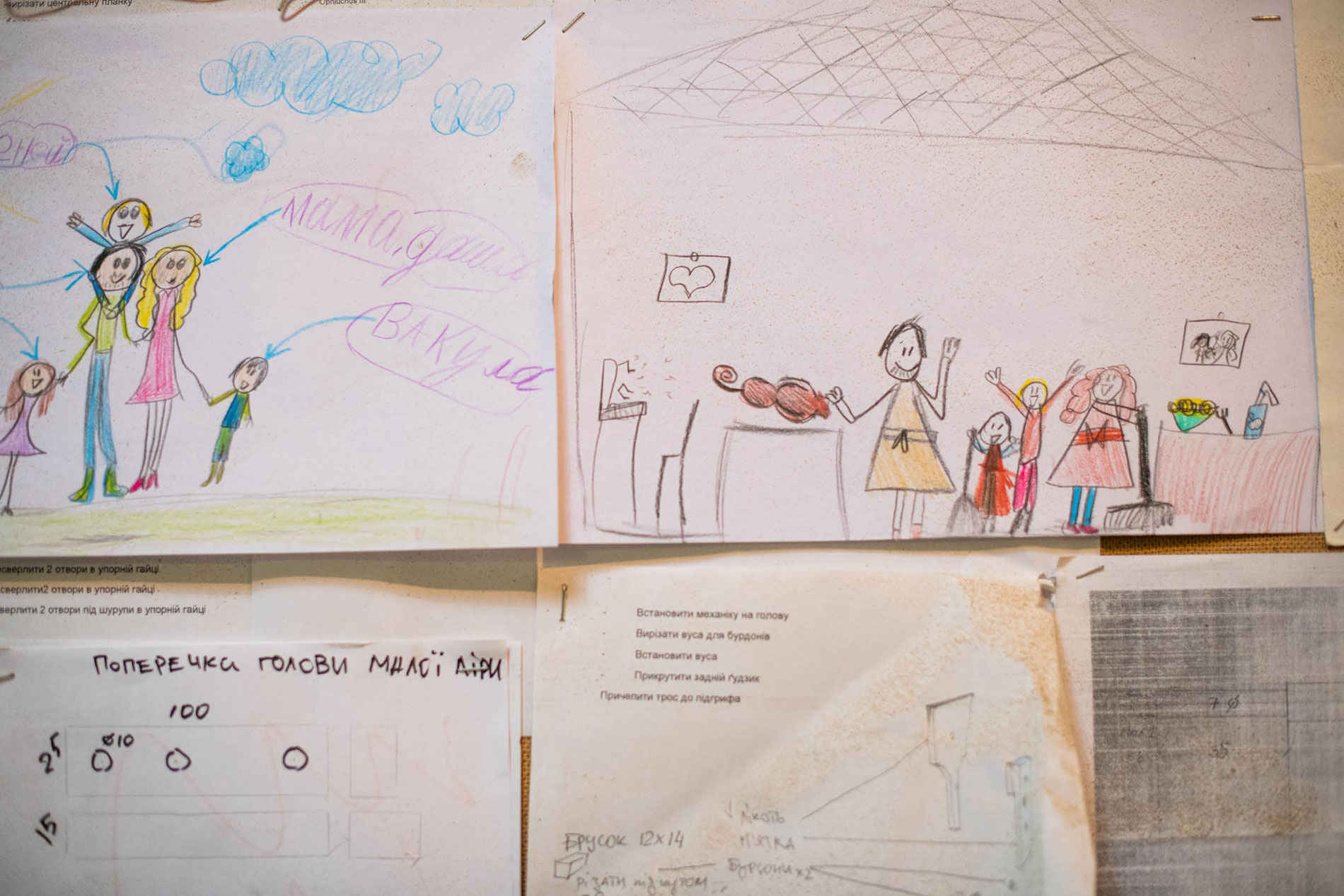

Hordii met his wife, Dariia Aloshkina, during his studies at the Lviv National Academy of Arts. She is also a sculptor, although she works mainly with paper. Dariia is a well-known craftswoman famous for her contribution to the revival of papercutting in Ukraine.

The Modern Lyre

Forbidden during the Soviet era, lyre art in Ukraine fell into decay. Today, Hordii is working hard to revive the craft. He says that although he follows traditions, the instruments he makes are technically modern. It typically takes Hordii several months to make one instrument. The shape of a lyre somewhat resembles that of a violin or viola, but there’s a difference in the way it’s played. It has a mechanic keyboard and a wheel instead of a straight bow.

— If you examine its features, the lyre is quite a fascinating instrument. Even its classification speaks volumes — it’s a friction instrument and belongs to the same family as violins and guitars! The sound is built in many different ways. There is a wheel-shaped bow. The guitar is built so that the strings can be pressed to the frets as needed. The lyre works the opposite way — sound is created by pressing the frets to the string. That’s why the lyre is a friction instrument.

Musical techniques differ as well. The crank needs to be spun and the keys pushed simultaneously, so that lyre can sound and vibrate. Although the lyre is thought to be a simple instrument, it’s not that straightforward at all.

— The lyre in and of itself is a prime example of combining sculpture with music but that’s only the case from the outset. Now, it’s become a challenge I face every time I make a new one. I can’t afford to make a worse instrument than the previous one anymore. I’ve become addicted to the process and to constant improvement. Moreover, I get a strong motivation from observing other craftsmen working. But nevertheless, I don’t feel any rivalry between us.

Lyres are not yet popular enough to warrant mass production. Renown craftsmen are famous for their pricey tools and long waiting list of customers. Unlike lyres, sculpting is more of a commercialized craft.

— I think a lot can be explained by comparing the exceeding number of sculptors to musical instruments makers. The most distant country I shipped a lyre to was South Korea. I’ve got one of mine in a museum in Malaysia, as well as Canada, England, Spain, Germany, Italy, Lithuania, Turkey. A lot of them are in Poland as well. My lyres are spread all over the world, you know

Most of my clients are collectors. There are also people willing to make music using my lyre. It is religious music mainly, such as psalms and gospels. When it comes to the materials required, the lyre presents a curious case. Sometimes I use old pianos or even shelves. Frequently, I come across the necessary materials while walking around in a park.

— If I lack materials, I can travel to Briukhovychi (a rural municipality near Lviv) or simply gather wood in parks, where I can get low-priced components. That is the main reason why I do not have suppliers abroad. I cannot compete with German manufacturers for now and their fares are much higher. Simplicity is a feature people like about my lyres most. If one learns how to play my instruments, they will have no difficulty practising on a more elaborate expensive German or French device. The standards of my keyboard correspond with European ones.

Grandpa`s Workshop

Hordii’s workshop is a site of creative clutter. Wooden samples and the instruments are all over the place. There are even unique antiques such as a restored Austrian lathe, which dates back to pre-World War I times. Hordii uses the lathe to sharpen lyre wheels. The walls are decorated with portraits and busts which are the legacy of his grandpa, the prominent sculptor Emmanuil Mysko.

— This is the family workshop of Emmanuil Mysko, where, apart from sculptures, lyres are made. My brother creates sculptures here, although, for the most part, lyre manufacturing occupies all available space.

By the way, Emmanuil was the one who created Ivan Franko’s bust in front of the Lviv National University. His most famous work is thought to be King Danylo’s bust at the International Airport of Lviv.

— Emmanuil Mysko was also an outstanding portraitist or “a master of the emotional portrait”. His portraits were a bit exaggerated. Some features were highlighted, as in caricature. If you take a closer look, you will see they are not that perfect. However, he had a unique gift of really conveying features of the character into the stone. Everything stored here is a part of his heritage and his legacy. The rest of his works are in museums all over the world. I want to establish a museum here someday, so I am only temporarily occupying the venue.

Can’t Buy It — Make It Yourself

Hordii Starukh made his first lyre in 2009, although he was introduced to its sound much earlier.

— I first listened to lyre music as a child and fell in love with it at once. My mom took me to the concert of Vasyl Nechepa. I don’t remember anything from that concert, truth be told. The only thing I do recall is an impressive sound. That was it.

.

Vasyl Nechepa

Ukrainian kobzar, lyrist, and singer.

Майстер взявся за це ремесло, бо хотів мати власну ліру. Купити її було задорого, тож вирішив виготовити інструмент самотужки:

— Купити було трохи дорого. Ну так, трохи — то було втричі дорожче, ніж я зараз роблю на продаж. Я вирішив зробити собі сам, бо я, відітєлі, скульптор, крутий пацан, я вмію з деревом працювати.

Hordii took up such a craft because he wanted to own a lyre. Since it was too expensive to buy, he decided to create it himself.

— Lyres were way too expensive. Three times pricier compared to my current selling rate. I made a decision to make a lyre on my own, as I am a sculptor, a cool guy, and I know how to work with wood.

His clients found Hordii the moment he started working on his very first lyre.

— There were already rumors spreading and the first client visited my workshop to buy a lyre. First, he practiced a bit and said it was awful and he wouldn’t buy it. Basically, this is how I started off.

Hordii did sell that first lyre. However, he got it back later to keep as a memory.

Hordii’s friend, Oles Koval, who is a lyrist himself, persuaded him to push on and continue manufacturing lyres. He recollects that it was Oles who played his very first lyre. He learned a lot from his friend. The craftsman jokes that such studying took him years, before lyre production became his main source of income.

— Since 2014, my work’s been bringing in a decent income. I’m making my fifty-first lyre now. It’s hard to believe! Back in 2014 I made maybe 10 lyres in total, and this year I’ve lost count of how many I’ve made. I’ve gotten into this drive.

From Sacred To Secular

The organistrum is an early ancestor to the lyre. The first mentions of this instrument date back to 9th century, and it served as the primary continuo instrument for Divine Mass. It did have a flaw though: it was very bulky and had to be played by two people at once — one would turn the crank, and the other played the keys as they both held it:

— It was a huge instrument, 2 meters wide. One person played the crank so to speak, as much as you can call that playing, and the second person just lifted the keys. That’s the merry tale of the ancient organistrum. When the organ started developing and improving, a smaller and lighter version of the instrument quickly appeared, and so it went out of style to carry a big organistrum.

Pretty soon, this lighter, simpler and more portable version of the organistrum wound its way into secular culture. And during Medieval times, the lyre became the most popular street music instrument. It’s interesting to note that each European country had its own version of the lyre. In France people changed the fate of this street instrument entirely. It got into the hands of talented, trained musicians and bards who took the lyre up to higher society, to the courts of Western Europe.

— Costume balls were the trendiest events in the 17th-18th centuries, truth be told. Craftsmen started receiving a decent sum of money to improve the technology of the keys, instrument, and framework as best they could. Thanks to these advancements, the lyre steadily developed into a more complex, professional instrument. They nailed it!

Ukrainian Lyre In Stockholm

If you go looking for two identical lyres in Ukraine, you’ll be looking for a while. Just like snowflakes, each one has something unique to it:

— That’s because there were never any artists who made all their instruments in one same, conventional way. I make them my way. I like to use techniques similar to those used by luthiers to make violins — I have a form I follow with certain patterns for each of my lyres. Ukrainian artists always made lyres in their own unique way, the way they knew how to. I’ve travelled all over the country and each lyre I’ve come across in various museums was unique. They are all unique and very interesting.

The lyre was always less popular in Ukraine than the Bandura (the most popular national classic string instrument). Lyre performers and bards in Ukraine were typically elderly men who were blind and would sing legends and keep them alive through song.

— Lyre artists were generally individuals who had lost their eyesight but of course there were also those that could see. I’m trying to learn how to feel the keys with my fingers without using my eyesight, to try and get a feel for whether the instrument would have been comfortable for them. The lyre really has a spiritual side to it as well because a lot of hymns and chants were typically performed on it. So it does have this connection to a religious character. These hymns typically played on the lyre were actually not taken from the bible, but they were traditional folk prayers. One piece that was also popular is the heroic epic tale called “Chym Khata Bahata” (what the home has to offer).

Hordii is convinced that you can play literally any piece you want on the lyre, not necessarily just traditional repertoire. Yet he respects its history, and tells about one of the oldest Ukrainian lyres that has survived to this day:

— I met a researcher who conducted a lot of searches for Ukrainian lyres that have made their way to other countries over the years. And he found one, in a museum Stockholm. The guys sent him a blueprint of this lyre upon his request. I have my own copy of it here.

And on this topic, our Ukrainian lyre does have its historic “relatives” in other countries. It happens to have a very simple construction in comparison to lyres from other nationalities however, as Hordii says, that does not diminish its features at all — simplicity is its strength!

— In France, a lot of money was invested in order to improve the French lyre back in the day, so it evolved a lot over time. In Ukraine it’s remained very close to its original form, with the classic 9-12 keys. Our lyres also have three strings, whereas the standard French ones have six.

Combining Sculpture With Music

Bright sound and unique design — that’s how I can describe a dugout lyre. It is an instrument made of one solid piece of wood. These were Hordii’s very first lyres, the ones he entered the craft with.

— Dugout lyres look pretty cool, although there is a drawback to them. Their looks are quite unpredictable up to their final stage of production.

The wood used for such instruments is not sawed but rather chopped. The process is very tedious. One day is far too little time to thin the wood enough to make it shine. But you have to be extra careful with that because wood gets spoiled when too thin:

— The same pattern was used in kobza and bandura manufacturing. Lyres are a bit tricky to produce as the history does not have records of lyres made adopting the dugout method. Some craftsmen in Ukraine do make these kinds of lyres, although some historians and experts argue with them, denying it. So, no one knows precisely whether it could have happened on Ukrainian territory or not. Hordii, however, doesn’t seem to care. He makes lyres the way he likes to.

— The thing is, when lyre performance died, the instrument was buried along with the body. That’s the reason why it is impossible to find out what an ancient lyre really looked like.

Speaking of the production process, the wood needs to be well-dried in order not to crumble. It takes a year usually, however if you chop it properly, the wood can be ready in a month. When Hordii started his craft, he was more into preparing wood rather than making the whole instrument from the outset:

— Basically, you take a piece of wood and shape it like a sculpture. Here I have the last lyre I made from poplar. I was supposed to send it to Canada, but when I put all the details together, I decided to keep it. Now I have this fancy lyre.

When Hordii took up the lyre craft, he constantly tried to experiment with its shape. Later on, the chose to follow one particular technique. There is one more way to make a lyre. You take a veneer sheet and simply curve it.

— A nice piece of wood is quite rare. I was lucky enough to find a guy who sells sycamore samples for the parquet production. These samples are amazing quality, though they can be pretty expensive.

The wood, which is destined to become a musical instrument, is dampened. Next, the sample is properly bent to its final form. The wood is placed on metal and swathed around a heated machine.

— I used to think it was something out of the ordinary that wood could be bent under the pressure of water and temperatures. Now I know, it actually makes sense.

Next come the upper and lower body. I need to do thorough calculations and certain size details in order to make a sound inner mechanism.

— Inserting keys is the most tricky and important moment. Connecting keys is the responsibility of my assistant. If you place them too loose or too hard, they will get stuck.

Then comes the installation of the wheel (bow), which creates the actual vibrations.

— I am a sculptor, an irrational perfectionist. If I make a single mistake, I have to start all over again. I accept the challenge and light risk every time I start a new lyre. You might think you have finished a new instrument, but then you notice a crooked wheel and you can throw that lyre away. It annoys me but makes me better at the same time.

Lyres used to be factory made in Soviet-era Ukraine. The Melnytse-Podilska factory of people’s instruments produced them in limited amounts. When Hordii stated his craft, there was only one kobza workshop and one craftsman. Things are far better today, as there are more and more people willing to revive the profession.

— I have a dream to make at least 300 lyres. The history surrounding this art, with the execution of our bards is a difficult one. I will never be able to completely restore the craft of lyre manufacturing, but I will at least do what I can to contribute to its revival and continue it. If I manage to make 300 lyres, my mission will be complete.