Of the over 8 million Armenians scattered around the globe, less than 3 million live in Armenia itself. Armenian churches and streets have become major attributes of many cities — from Lviv to Singapore. In Ukraine there are about 100 thousand Armenians. The works of a famous film director Sergei Parajanov were produced at the intersection of Armenian and Ukrainian cultures. The same is true for the works of Roman Balayan (film director — ed.) and Boris Eghiazaryan (artist — ed.). But what do we know about Armenians living in Ukraine?

The seeds of Armenian culture are scattered all over Ukraine. Like pomegranate seeds planted long ago, the culture has become so deeply rooted in this land, that it seems as if it has always grown here. Armenians became priests, musicians, artisans, merchants. They created their lives in places where centuries of their ancestors moved to, assimilated into, and where they formed new communities and churches to unite and maintain their culture. Large Armenian diaspora is found in the USA, France, Georgia, Iran, Syria, Argentina, Ukraine, and other countries.

The first Armenians settled on Ukrainian land as early as the 10-11th centuries, as they fled from the Arabs and Seljuks. Back then there was a mass migration of Armenians to the Crimean Peninsula and to Kyiv (Surb Khach Monastery located in the mountains near Staryi Krym is still one of the most famous Armenian monasteries in Ukraine). The Armenian kingdom of Cilicia appeared on the territory of modern Turkey in the 11th century and existed until the 14th century. After its fall, Armenians began travelling across Europe. First they headed to Poland and from there — to Ukraine. The strongest communities formed on territories which were then a part of the Kingdom of Halych and Volyn — in Lviv and Kamianets-Podilskyi — around the 15th century. During this period, Halych territory became a part of the Polish kingdom and the Catholicoi (the patriarchs of the Armenian Church — ed.) travelled to Lviv for the first time to collect tribute from local Armenians. For the next 300 years church tribute was collected from locals.

The Armenian community expanded gradually — they opened new churches and schools, they developed local crafts and were eventually granted autonomy by the Polish king. Many towns had their own Armenian Streets. On every such street Armenians roasted and brewed coffee, wove carpets, and made jewellery and leather goods. In other words, they were really putting down roots on this land.

From the beginning of the 20th century, there were three more large waves of Armenian immigration to Ukraine. But later some of those immigrants faced brutal deportation. Along with Crimean Tatars, Bulgarians and Greeks, the Armenians of Crimea were forcibly deported from the peninsula in 1944. The Soviets accused them of collaborating with Nazi Germany. They were exiled to forced settlements in Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, and Russia. Of the 38,455 people deported, 9,821 were Armenians.

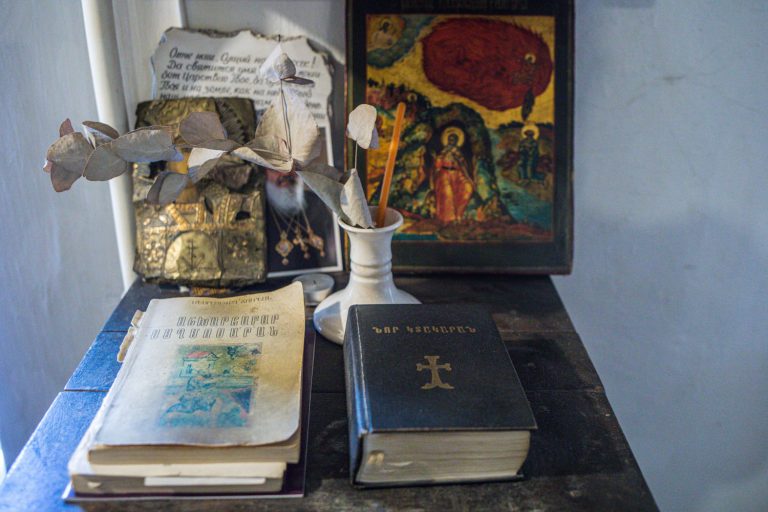

The Armenian Church in Ukraine. Marcos Hovhannisyan

The Church is an important symbol of Armenia worldwide. Historically, ethnicity and faith were interrelated for Armenians. Nearly every Armenian was traditionally a Christian. They were among the first to convert to Christian faith in the year 301.

In the Armenian church in Kyiv they are preparing to celebrate Christmas and to perform the matagh ritual during the christening. This ritual is performed for this and many other important occasions in parishioners’ lives.

The church in Kyiv is currently under soon-to-be-completed construction that would make it the largest Armenian church in Eastern Europe. The church is attended by the parishioners from Kyiv and the surrounding region, from Zhytomyr, and many other Ukrainian cities and towns.

The Armenian ritual of sacrifice called ‘matagh’ is a church tradition. Traditionally this was a ritual offering of a lamb or another animal to thank God for his mercy. Bishop Marcos Hovhannisyan, the Primate of the Ukrainian Diocese of the Armenian Apostolic Church, explains that today matagh usually takes the form of a shared meal which is prepared for occasions such as joyous family moments.

— It is as if you are sharing your joy, which you promised to share. Matagh can be in the form of meat or bread that is prepared and shared with all those who need it most. It’s a Christian church tradition.

Marcos was born in Armenia. He did not intend to become a priest. He had never considered this before and had an aptitude for engineering. But his life changed when fate led him to Etchmiadzin, where he entered the seminary. Today Bishop Marcos leads services across Ukraine.

— I have only warm words to say about Ukraine — it is very dear to us. Through history, the country became dear to every Armenian and to all of the members of the Armenian Apostolic Church. The Armenian Church has been operating in Ukraine for thousands of years without any restrictions or difficulties. Thanks to God, we have mutual understanding, because we are all one and we form one Church of Christ. We may have different denominations but the Church is one.

Etchmiadzin

Etchmiadzin Cathedral is the main spiritual centre for all Armenians. It is located near Yerevan, the capital of Armenia. It is the seat of the Catholicos and also the place where all seminaries operate.

slideshow

The Armenian Church has existed in Ukraine for a long time. The Armenians built their first temples during the era of Kyivan Rus. One of the oldest churches is in Lviv. The Armenian Cathedral of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary, which is a UNESCO World Heritage site, was built by a Lviv architect Doring in the 16th century. In 1651, when Kyiv was captured by Janusz Radziwiłł’s army, fires destroyed many sacred places including Armenian places of worship. When St Sophia’s Cathedral in Kyiv was finally restored, the Armenians were offered a chapel within the cathedral for their spiritual and religious needs. In other words, Armenians are so deeply integrated into the Ukrainian community, that they were not left without a place for worship.

The Armenian Apostolic Church in Ukraine, which is loyal to the Mother See of Holy Etchmiadzin, was established in 1991 after the dissolution of the Soviet Union. According to Bishop Marcos Hovhannisyan, there are twelve Armenian priests, two deacons, and fourteen active churches in Ukraine.

Another eloquent Armenian symbol is the khachkar. It can be found wherever there are Armenians. There are several khachkars erected in Kyiv. One of them can be seen in Politseiskyi Sadok park in the city centre, another one is near St Sophia’s Cathedral. One won’t find two identical khachkars. Most often they were erected near churches. And it is the church that unifies the whole Armenian community, which is like one large family.

Khachkar

A large stone slab bearing a carved cross decorated with Armenian ornamentation.

Christmas. Anik’s family.

— Here come the walnuts, they are ready.

— Can I chop up the nuts, Mum?

— Are you sure you want to?

— Yes, please.

Little Tigran meticulously chops the walnuts to prepare them for the Christmas dinner. This year Anik Ergnyan and her whole family will celebrate Christmas together — the first time in 30 years. This occasion calls for a grand celebration and a great feast. At the heart of the Armenian culture is their generous hospitality, which is passed down from generation to generation.

If one happens to be a guest at an Armenian’s home, one must embrace this characteristic hospitality. Moreover, strong family bonds among Armenians are the foundation of the community providing support whether one is at home or abroad, escaping a tough situation or relationship, or looking for guidance.

The main Armenian religious festivals are Christmas, Easter (Zatik), the Transfiguration of Christ, the Dormition of Mary, the Assumption of Mary, and the Exaltation of the Holy Cross. Armenians, along with the followers of Eastern Christianity, celebrate Christmas on 6 January.

slideshow

Cooking is a constant feature of all family holidays. Anik’s family finalises preparations for the Christmas dinner. Unlike some cultures, Armenians do not follow the tradition of a twelve-dish Christmas dinner. Anik’s daughter Srbuhi says that the recipes should be complex to represent prosperity.

— The main course is rice. It symbolises our pure and untarnished nation. The rice is topped up with large roasted dried fruits that symbolise the saints. This course is served in every Armenian household.

Another mandatory course is fish, which is a symbol of Christianity. The fish can be roasted or boiled.

— The Armenians have this tradition of topping boiled salmon with pomegranate seeds. This combination of salmon, pomegranate, and tarragon is delicious.

Anik was born in Armenia, where she spent her early years. But it has been 30 years since she and her husband moved to Shepetivka in Ukraine as young kids. Back then, they thought it would be temporary — just until the situation back home improved. This was a challenging time for Armenia as the country struggled to gain independence.

— It’s always a challenging path — to start life anew from just one suitcase, six plates, one saucepan, and with three kids. In 1993–1995, Ukraine was in a far better condition than Armenia. When our relatives moved here, we followed them. And as it happened, there were no drastic changes back there (in Armenia — ed.), and the children’s school was here. We did not want to interrupt their learning. Quite the contrary, we wanted to ensure a decent education. The conditions in Armenia back then were very poor — families relied on wood burning stoves, houses had no gas or water supplies. There was access to electricity for only one hour per day.

slideshow

The Armenian Christmas dinner must include a lot of sweets. Gata is one of the traditional pastry varieties. The ingredients are quite simple: flour, butter, and sugar. They are mixed together and baked. Gata is prepared differently in Ukraine and in Armenia. Once baked, the round gata is sliced into twelve pieces, corresponding to the twelve months of the year, and is offered to all guests.

According to the Christmas tradition, younger family members visit the older ones, says Srbuhi:

— In Armenia there are two major cults: the cult of the family and the cult of the elderly. Your family and respect for older generations come first — it’s like this everywhere and always. That is why the whole family gathers together to celebrate all major church holidays. The more guests, the better.

Tigran brings in a plate with gata. It will be cut into twelve pieces and served in honour of the deceased family members. This is a way of remembering those who are no longer with us, and to sweeten the bittersweet memories.

The Art Community. Boris Eghiazaryan

From the yard near his workshop Boris Eghiazaryan loves to admire the gleaming gold of domes on the Church of the Intercession. Previously, this building had been a dormitory for a conservatoire until it was flooded. Then the artists united to restore the roof, clean up the space and set up their studios here.

For over 15 years the All-Ukrainian Creative Union of Artists “BZH-ART” has resided here. Each time the artists jokingly say to one another: “That’s it, it’s time to disband for good, everyone is tired of each other”. But of course they are not serious.

— As soon as these thoughts start crossing your mind, you see how lonely your studio would be. Where would you go? This is your place. This is your private monastic cell. So even though we bother one another, we all love each other too.

Some orange scraps of paper that have been there since the Orange Revolution can be seen on the door to Boris Eghiazaryan’s workshop. Back then the scraps composed a square, and this place was called the Organisation of Artists “The Orange Square”, it included Mykola Zhuravel and Boris Eghiazaryan among other artists. They organised various exhibitions and art events.

Boris Eghiazaryan was born in the town of Aparan in Armenia. He began drawing at the age of five. Boris recalls that he was not a very good student. But he was very diligent with his drawing.

— On a sheet of paper I would outline a little square and then I would draw all sorts of little stories inside. No one could persuade me to make a drawing on the full piece of paper. I’m an old Armenian miniaturist. A teacher once put a match on a sheet of paper, asked me to outline it and said: “Draw your fantasies inside this frame”. I then drew an even smaller square within the outline of the match and proceeded to draw inside it.

slideshow

In his youth, Eghiazaryan became fascinated by mural painting. So he moved to St Petersburg (called Leningrad back then) to master this art. In 1988 all of his murals were destroyed during a devastating earthquake in Armenia. There was nothing left of his old works, not even a photo. Boris is still heartbroken.

After meeting and marrying Iryna, Boris moved to Kyiv to continue studying mural painting at the Kyiv Art Academy. The story of how he ended up in Ukraine is Boris’ favourite.

— I tell everyone that I met a Ukrainian girl in Crimea, who tricked me into marriage.

He was 19 when he married Iryna. His parents were delighted with their couple. Boris himself was taken by Iryna:

— We have the same taste in everything, even when it comes to painting a nude figure or a portrait, even when it’s of a woman. We may sometimes be sitting in a café and suddenly react to something at the same time: “Oh wow, look!”

Many of Eghiazaryan’s watercolour and collage series have found their way to museums across Ukraine and to private collections abroad. One of his well-known watercolour series is called A Pomegranate, where in each pomegranate a new theme is depicted.

— I painted a lot of pomegranates. And usually I paint them when I’m emotionally or mentally overwhelmed.

After finishing his education in Kyiv, Boris wanted to bring some things back to Armenia. At that time he was making sculptures. So he took all of his 35 or 36 sculptures and packed them into shipping containers. During shipping, the containers were dropped from a great height. Upon his arrival to Armenia, instead of his works, Boris gathered together a pile of shards of clay.

— Not a single sculpture survived. Three years of work — day in and day out — were gone. And after that my workshop in Armenia burned down with all my works again.

Between 1988 and 1993 Boris was living in Armenia where the Armenian revolution and anti-Soviet movement were beginning. At the same time, the war with the neighbouring Azerbaijan led to the conflicts in Nagorno-Karabakh. Boris volunteered to join the military unit from his village to defend his country’s borders.

— I could not leave Armenia for Kyiv during those challenging times. Instead, my wife would visit me for a month or two ‘to warm me up’. She would stay with me for a while and then return to her ageing parents and to our daughter.

At some point during the 90’s Boris’ friends invited him to move to the USA. They kept telling him, “We’ll help you with everything and take care of anything you need. You’ll become a highly-paid artist here”. And then in the late 90’s, there was an exhibition organised by a Swiss financier, who invested in Ukraine, Armenia, Georgia, Belarus, and other post-Soviet countries. He invited Boris to move to Switzerland to live and to exhibit there.

— I said: No, thanks. If I’m not going back to Armenia, then I will stay here (in Ukraine — ed.). The European lifestyle looks interesting. But the personal lives of Europeans are confined to a small circle of people. While in Ukraine — as in Armenia — there is this feeling that strangers are also like family, friendship is different, and interactions are more authentic. The creative friendship between artists is different. This is the life that I love in Ukraine.

The Nagorno-Karabakh conflict

A military conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan sparked in 1987 and lasted until 1994. It arose from disputes over control of the Nagorno-Karabakh region. The clashes there continued even after the ceasefire was signed. In 2020 the conflict escalated again.

slideshow

Boris has been living in Ukraine for nearly 30 years. It was not easy for him to find the best way to depict Ukrainian landscapes in his paintings. But now, he says, he sees the proper way to paint Ukrainian woods, sunsets and dawns.

— Everything here is green. It’s vividly green, deliciously green. Solid green. While in Armenia the sunlight is such that the same green tree will be tinted with yellow, orange, or even red in places. The tree’s shadow is dark blue. Here I began to recognise all this delicateness and harmony. It’s a different kind of beauty, a graceful beauty.

The Ukrainian artistic community has a big impact on Boris, Ukrainian painters do in particular. He is always expected to create something new, which keeps him from depression or stagnation. Boris enjoys that.

— As an artist here, I’m different. For Armenians I am different as well. In Ukraine people think that I’m a typical Armenian painter. This is not the case. In Armenia I am also unlike other artists. We have similarities, because in Armenia every other person is an artist, but a different one.

The late Svitlana Shcherbatiuk, Sergei Parajanov’s wife, once said that Ukrainian musicality wove into Parajanov’s Armenian temper. The same happened to Boris.

Roman Balayan. The Parajanov phenomenon

On the grounds of the Oleksandr Dovzhenko National Film Studio there is a memorial to Sergei Parajanov. Close by there is an office of yet another Ukrainian film director of Armenian origin — Roman Balayan. He is a good friend of Boris Eghiazaryan’s.

— Boria (Boris Eghiazaryan — ed.) thinks I’m a genius, but I think I’m just one of a thousand others.

These days Roman Balayan manages the Illusion Films company, which is based on the territory of the Dovzhenko Film Studio. Earlier, he was just an assistant to other directors, but later in 1970 became a director himself at this very studio.

Roman Balayan was born in 1941 in Nagorno-Karabakh, in the village of Nerqin Horatagh.

— The first seven years of my childhood were continuous overeating. My father was one of the first in the village to be killed in the war. The whole village pitied and loved me. When I was walking down the street, people would pat me on the head, sneak something into my pocket. Someone would even steal oranges for me. My mom was the only doctor for five villages. She rode a horse and carried a pistol!

First he studied in Yerevan in the film directing faculty and later at the Kyiv National Ivan Karpenko-Karyi Theatre, Cinema and Television University. In 1977, eight years after graduation, Roman’s film Biryuk (Lone Wolf — ed.) was entered for the Berlinale.

Balayan received a number of proposals to shoot films about the Soviet rule or coal miners, but he always filmed only what he wanted.

Sergei Parajanov

A Ukrainian and Armenian film director. One of the representatives of the Ukrainian Poetic Cinema movement.

Balayan knew Parajanov well. He was Parajanov’s apprentice, but, he claims, did not turn into a follower. Roman met Parajanov before watching Sergei’s famous film Tini Zabutykh Predkiv (Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors — ed.). Roman recalls how he was skeptical about Sergei himself, still he was struck by the film. From that moment, Parajanov became ‘the god and the king’ of the film industry for Roman. Later Parajanov supported many of Balayan’s creative ideas.

— I was going through the official process of receiving broadcasting clearance from the government for my first film Efekt Romashkina (Romashkin’s Effect — ed.) when suddenly the central television manager received a call from Parajanov. How did he find out that I was in Moscow and was trying to get clearance? He came to watch the film’s preview. By then everyone knew I thought my own movie was terrible. The preview session ended and there was a lot of criticism, as expected. Then Parajanov stood up and said: “Well, wait, if you cut this scene and that one, and then repeat this part, the whole thing will become just what you need!”

After Parajanov’s death, Balayan helped shoot the film Nich u Muzei Paradzhanova (A Night at Parajanov Museum — ed.) in honor of his genius.

Among the films shot in Ukraine, the most important ones that reflect Sergei Parajanov’s legacy are: Tini Zabutykh Predkiv and Kolir hranata (The Color of Pomegranates — ed.). The first film, based on the novella by Ukrainian writer Mykhailo Kotsiubynskyi, was created in tandem with Yurii Illienko and Ivan Mykolaichuk, and was praised for conveying the poetry of Ukraine. The second film conveys the poetry of Armenia and the biography of one of Armenia’s greatest poets Sayat-Nova, which reflects Parajanov’s own emotional biography.

Sergei Parajanov was a son of several nations. An Armenian born in Georgia, he lived in Ukraine for many years. As such, he was able to perceive individual features of each nation, which is why Tini Zabutykh Predkiv and Kolir hranata were born. Those films started a new aesthetic, where each episode became a card, or a picture, or even an icon. He united many artists around himself starting from the 60’s, who then became his friends or followers. Later he had to pay dearly for his habit of acting and speaking freely. He described himself as “an Armenian, who was born in Tbilisi and was sent to a Russian prison for being a Ukrainian nationalist”. Because his films did not comply with Soviet standards, Sergei Parajanov was arrested three times. His films were ranked among the greatest films of all time, and Tini Zabutykh Predkiv is recognised as one of the top 100 best films in the world.

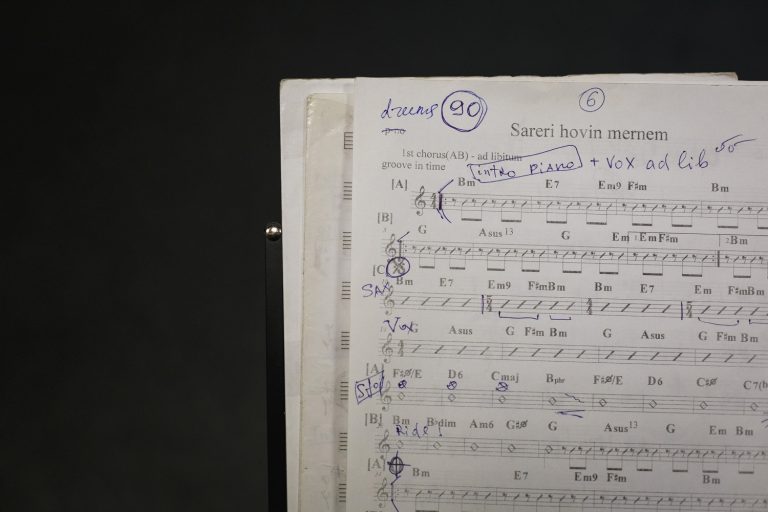

The song of Armenians. The Martirosyan sisters

— Have you been to our part of the world, have you seen our gardens, our home, have you seen what has been ours since the beginning of our lives? How is it there? How are our fruits, flowers, our lands, our region?

‘Krunk’ is the Armenian word for a crane, a symbolic bird in their culture. There is also a song of the same name, which is important to all Armenians. This song is about the genocide in the beginning of the 20th century when Armenians were forced to leave behind everything they had and to search for a new home. Those who were lucky to survive.

Kristina and Laura Martirosyan, both singers and ethno-jazz musicians, start their rehearsal with this very song because it was with this song that their musical careers began:

— The first person from whom we heard the Armenian songs was our grandmother. Oh, did she sing! You should have heard her. She probably suffered from that tragedy the most. She loved Ukraine, but could not accept that she no longer had her own home. That is why when we sing Krunk, it always brings recollections of our grandmother.

The Martirosyan sisters were born in Kharkiv, Ukraine. When they were children, their parents sent Laura and Kristina to live with their grandparents in Azerbaijan, to a small Armenian settlement in the city of Ganja (Kirovabad back then). They lived there until the start of the second Armenian Genocide, in the 1980’s. Kristina was then 6 and Laura was 2.5 years old.

— It became very hard for us because we had to hide. People were murdered in the middle of the day. People were not allowed to leave or enter the city. We were hiding in our house. Our Mum was in Kharkiv at that time but somehow managed to arrange for the two of us to be brought to Ukraine. In the middle of the night we were hidden in furniture and carpets, carried out and driven away. And this is how we got to the airport.

Armenian Genocide of 1915

The systematic mass murder and expulsion of ethnic Armenians carried out in the regions controlled by the Ottoman government.

slideshow

The girls returned to Kharkiv where they subsequently started school.

The Armenian Genocide, or the Great Crime, was carried out in 1915 on the territories controlled by the Ottoman Empire. The Armenian people were massacred or deported. The majority of the Armenian diaspora was formed by the fugitives from the Ottoman Empire. The Armenian Genocide is considered the second biggest act of genocide after the Holocaust.

— We are the Armenians who lived in the territory of Azerbaijan. After the first genocide, Armenians scattered like pomegranate seeds.

Today there are fewer Armenians living within Armenia than there are abroad. An extensive global Armenian community was formed during those years, as a result of the second wave of emigration. This time the Armenian people were fleeing not the Ottoman Empire, but Azerbaijan. Ukraine became their new home and the place that saved their lives.

Laura and Kristina’s mum always wished that they would sing together. The girls recall how the whole family always sang together whenever they had guests over. There was not an occasion without singing, dancing, or playing Armenian musical instruments. Even after the events of 1988, their grandmother Liudmyla always said to their mother:

— Nina, you must take them to learn music! I listen to their ‘concerts’ here all day long! They won’t sit quietly even for a minute!

Everywhere Armenians live there is a community and almost everywhere there’s a dance troupe. Additionally, they teach folk songs and the Armenian language in the community centre. The girls continued to attend dance classes and perform duets in concerts at the Armenian community in Kharkiv. Their mother was one of those who helped to build the Armenian church in Kharkiv and to organise a Sunday school. Thanks to their mother, Laura learned how to write and read in Armenian. Their mother was a journalist by vocation — she managed the community’s newspaper Kanch (which in Armeinan means ‘call’). She wrote a lot about the Armeinan people in Kharkiv and, along with the others, worked to revive the Armenian culture.

The girls completed their higher education in music at the Kharkiv Conservatoire. At first they didn’t sing together. But after they formed a band, Armenian songs became a part of their repertoire over time. Their music is a mix of European jazz and Armenian melodies.

slideshow

Now a duo, they performed concerts in Armenia. There the girls visited various craftspeople who create folk instruments and with time they mastered playing many of the instruments themselves. Among them is the dhol, an ethnic Armenian drum. They already own a duduk (a woodwind instrument made of apricot wood), and their mother gifted them a zurna (also a woodwind instrument).

— Somehow we don’t feel 100% Armenian. We have Armenian ancestry, and we are Armenians by blood. But people live in the infinite space of life, and they change, develop, and are filled with breaths of new life through time. And this new understanding, this new sensation from every person we meet in our path gives us a feeling that we all matter, that we’re not strangers. So we feel 100% Ukrainian and Armenian. And jazz is very much like speaking foreign languages, we speak either Ukrainian or Armenian.

Kristina thinks Ukrainians and Armenians have a lot in common, including their big hearts, their soulfulness and even their melodies. Just by sound, the musical traditions are different, but the similarity comes with the songs. Obviously there were some challenging moments in their childhood after they had moved to Ukraine. When the girls quarrelled with other kids and came home in tears, their grandma used to tell them, “If they offend you, next time, you have to tell them, ‘I’m proud to be Armenian. Are you proud to be Ukrainian?’”.

The girls are working on a music album about the Armenian Genocide. They lived through one of the genocides themselves and it’s still a painful memory:

— During the Maidan (the protest movement in Ukraine in 2013-2014 — ed.) there was this burst of energy, the whole country was involved — this was a trigger for us! This brought back terrifying memories! To witness again everything I lived through in my childhood! I saw and remembered all of it. We could not bring ourselves to sing during those times (during the Ukrainian Revolution of Dignity — ed.).

The women believe it is important to talk about it (the Genocide — ed.) a lot, to create music about it, and to research it so that people can finally learn from those mistakes and never allow such things to happen again.

— For us, this topic will always be relevant. And the one about Ukraine too. We live here and breathe this air, and we can’t help singing about the Ukrainian and the Armeinan. It’s inside of us.

Pomegranate juice spills out onto the white linen and one can hear, “I am a man whose life and soul are torture”. This is what the cult Armenian poet and singer Sayat-Nova writes in his lyrics, and this is what Sergei Parajanov shows in his films. Armenians who dream day and night about their Mount Ararat are just like the pomegranate seeds — they are many, and they all sit close to one another. They can’t imagine themselves without their land and yet, most of them live abroad. Armenians grow deep roots, but are scattered across the globe for many reasons: the genocides, deportations, and wars. They follow their memories to the stone khachkars somewhere in the middle of a park, or to the symbols in their paintings, music, or films. They continue to gather around their family tables, which radiate the same hospitality as did the ones that stood in Armenian land long ago, under old walnut and fragrant apricot trees. Today, just as hundreds years ago.

supported by

Material prepared with support of United States Agency for International Development (USAID)