The Austrian community in Ukraine primarily lives in Zakarpattia in the villages of Ust-Chorna, Nimetska Mokra and in the towns and villages located in the valley along the Teresevi river. Despite its small size, the Austrian community here continues to celebrate itsown traditional holidays, among which the most famous is Scheiben, a midsummer holiday, which is called Shayblyky here.

Arriving in Ust-Chorna in Zakarpattia, Austrians brought with them an old tradition that celebrated the summer solstice, called Sonnenwende. One specific holiday is called “Scheiben” and is similar to Ivan Kupala Day, which is a traditional summer holiday in Ukraine. Scheiben is celebrated over the course of three days, from the 21 to the 23 of June.

In Austria the traditional celebrations of Sonnenwende are still widespread throughout the different regions and annually attract many tourists. Sonnenwende is considered a UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage. Though, the Austrians from Zakarpattia have their very own way of celebrating this unique tradition preserved from long ago.

In the evening, residents of Ust-Chorna hike up the hill and wait for the event to begin. Amongst the crowd of people a single man’s voice can be heard:

— This is called the mountain Podyna. For over 420 years we have been hitting shayblyky (wooden tiles) — ever since the founding of Ust-Chorna.

Scheiben. Petro

The head of the village council, Petro Kostiak has joined in the traditional celebration of Scheiben since he was a child. His 18-month-old daughter also carved wooden tiles for this year’s holiday:

— It’s easy to preserve this tradition because we know it so well. I try to help all nationalities because I don’t see any difference if a person asks for help.

Petro’s parents and grandfather were Ukrainians. Mykola, his cousin, is a German. His mother had German roots and his father was a Ukrainian.

— We don’t want to have divisions amongst us between the Hungarians, Germans, and others. We’re all Ust-Chornians, but some are simply from a Hungarian family and others are from a German family. While one has a mother with German ancestry, another has a father and a mother who are German because their grandmother and grandfather were also Germans.

According to Petro, only several dozen people of Austrian heritage remain in Ust-Chorna. Many have left during his time, but there are still some that decided to remain:

— We are all one. Simply they (referring to the Austrians) support their traditions and we support theirs and ours, and they also support ours. We celebrate Christmas according to both traditions, theirs and ours. We sing our carols in German and Ukrainian. It’s wonderful that we live like this here.

Locals begin to prepare Scheiben long in advance: they erect two wooden pillars on the hill (one slightly above the other). On these columns, they construct something similar to a springboard.

Wooden tiles are cut from hardwood. Residents of Ust-Chorna have a local term for these wooden tiles, the shayblyky, from the words of a song. It is a collocation of the words “scheiben schlag”, which literally translates as “beat the puck”.

Shayblyky are hand cut wooden square tiles 10 by 10 centimeters that have a hole in the middle and are placed on a stick. People of all ages, old, young, and children alike, heat the tiles over a fire and then throw the wooden tiles up in the air at a specific angle.

While the tiles are still hot they begin to glow brightly in the dark and participants use the springboard or a bench to launch the tiles into the air by hitting it with a stick. The aim is to get the tiles to fly as far as possible in the air before falling to the ground, leaving a long trail of bright sparks behind.

slideshow

When they succeed in directly hitting the tiles into the air, then people sing, “Sonnenwende, Sonnenwende, Scheiben schlug” and then they call the name of the person who hit the shayblyky, like “Josef schlug.” If they hit the tile well, then they say “Ging gut” which means “Super!” And if they did not hit the tile well then they say “Hinten schlug”, which means that a tile flew badly and ended up under the bench.

The sticks that are used to launch the shaiblyky are made of birch because they bend well and do not burn easily. When burning the shayblyky over the fire it’s important to only heat up the tile and not the stick, otherwise the stick will break when hitting the tiles. Once the shayblyky were meant to be hit above the towns. Now they have relocated to a different part of the valley. In Ust-Chorna there is a superstition that throughout the summer solstice the grass can not be cut down. This isn’t because of the holiday, but because usually there are thunderstorms and heavy rain during this time.

Petro Kostiak organizes shayblyky hitting tournaments to encourage local involvement in these celebrations. Prizes are available from the village council — for example a certificate, or a pint of beer, soda, or chocolate.

Earlier, the whole family used to gather together on Scheiben. The father had to cut the wooden tiles for his son, the son was expected to hit the tiles well so the father could praise him. This was how living traditions were transferred: the father taught the son how to do everything properly. Families celebrated both privately and with other families. Everyone gathered as a collective and walked together, people strolled along playing the accordion and there were competitions.

While the boys went after their wooden tiles, the girls sang on the benches — everything is very similar to an Ivan Kupala Day celebration. In earlier times there was a different meaning attached to the ritual of burning the wooden tiles. The original purpose for the holiday was to thank nature for the long summer days, for the sun that had stayed high in the sky all day and for the long hours provided by the day so that people had enough time to finish all their work and chores. People often write their wishes on the shaiblyk and believe that they will come true depending on how well the are hit with the stick. Sometimes the shayblyky are dedicated to someone. A boy may hit the shayblyky on behalf of a girl he likes, or vice versa. But you are only allowed to hit the shayblyky once.

slideshow

If you analyze the holiday as a pre-Christian paganistic ritual, then the bonfire that heats the pieces of wood can be understood as a symbol or the sun, and the shayblyky are the sunrays. It’s flares of light are a reminder that warmth is a gift from the heavenly bodies. After this holiday the days begin to shorten.

The older residents of Ust-Chorna don’t always have the strength to hike up the hill to participate in the celebrations. If the rains make the road conditions to the top of the hill too difficult, the older people will not be able to go even if they wanted to. Which is why these days the holiday is becoming more of a get together for the youth. There are two gathering points. One group is organized by Petro Kostiak on the hill where the shayblyky are hit by the first Austrians here, long ago. The second group is organized by a local businessman, in the valley below and people celebrate the holiday by building a campfire, frying up some food, and singing songs and playing guitar.

Horbases

There are no families with 100 % Austrian heritage in Ust-Chorna. All families have mixed heritage these days.

But earlier, families here had very noticeable Austrian last names such as Goltzberger, Schweiger, and Reisenberger. Reisenberger means “wanderer of the mountains”. And Holtzberger means “ruler of the mountain woods”, or in other words, a forester.

The most common last names in the village today are Kais and Horbas. These are often considered German names, but this is not altogether correct. During WWII Germany offered asylum to the Austrians, and when the Austrians returned home people wrote in their passports that they were Germans.

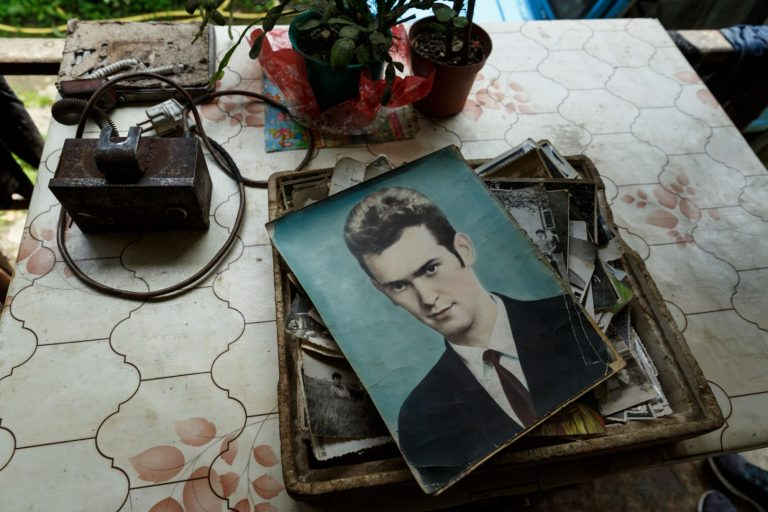

Yosyp and Imre Horbas are cousins, ethnic Austrians, who live in the village. During WWII the father of one of them went to the village Dubove and stayed there until later returning to Ust-Chorna. The parents of the other left for Germany but then after awhile returned to Zakarpattia.

— We were born here. His father worked up in the forests above and he worked in a garage. We have known each other since we were kids. We’re family, though distantly related. We’re from one family. His grandfather and my grandfather, they are Horbases. Something like that anyway. My grandfather Horbas and your grandfather were brothers back in the third or fourth generation. The important thing is that we are all Horbases. And all Horbases are tall.

Yosyp Horbas is 77 years old. He drives his blue car, works in his large garden, and has fifteen grandchildren and three great grandchildren. His grandfather once lived in the nearby village of Bushtyno. Yosyp’s family left when he was a year and a half to live in Germany. They lived in Germany up until 1948. During the Soviet times Austrian families like his were not allowed to return to this area.

— Everything was fine in Germany, but our souls are here. Here is where we are natives and have all our natural habits. You don’t ever forget that.

Yosyp values the nature the most. Here he enjoys the winds, water, and climate:

— Winter is not very cold here and summers are not very hot. The insects are not poisonous. We don’t have any dangerous snakes or dangerous crocodiles. And delicious berries and mushrooms grow here. We have a little paradise here.

He loves everything here. When he was young he would hike through the mountains and valleys. His father loved to walk through nature.

— There is a specific flower, the Edelweiss, that grows here in the Carpathians. It grows far away though, you need to travel all day along the valley to the lake at the top to reach it. We would make the trek every year to find it. We’d wake up early and go. Oh the beauty!

Yosyp Horbas’ three sisters live in Germany. He has also been there but he returned home to Zakarpattia after his home was destroyed and he had to rebuild everything.

— There’s a German song where the lyrics go, ‘Where my cradle stands, there is my motherland. There (in Germany) it is beautiful, but it is not for me.

Austrians traditionally worked in the forest. Yosyp’s father Wilhelm was a very hardworking forester. People would work in forests 20, 30, and sometimes even 40 kilometers away. They lived the entire week away in the forests — on Monday they would leave and on Saturday they would return home. They lived in little lodges where they would cook and sleep alone. The families would remain in the village.

Yosyp learned carpentry and woodworking from his father. He began to learn when he was 13 years old. After his army service he switched from being a foreman at a lumber mill to a television station where he focused on television transmitters.

In the army Yosyp served in the radio engineering division, which is how he learned about broadcasting and radio transmission. He fell in love with electronics. When he read in the newspaper that in Uzhhorod they were looking for technicians he went to meet the manager.

— I didn’t have any education and you needed to be a first class specialist from a technical college. After talking with the management they agreed to take me on, and that was that. I stayed there and began working. My schedule was one week there and three weeks at home. I worked there for 45 years.

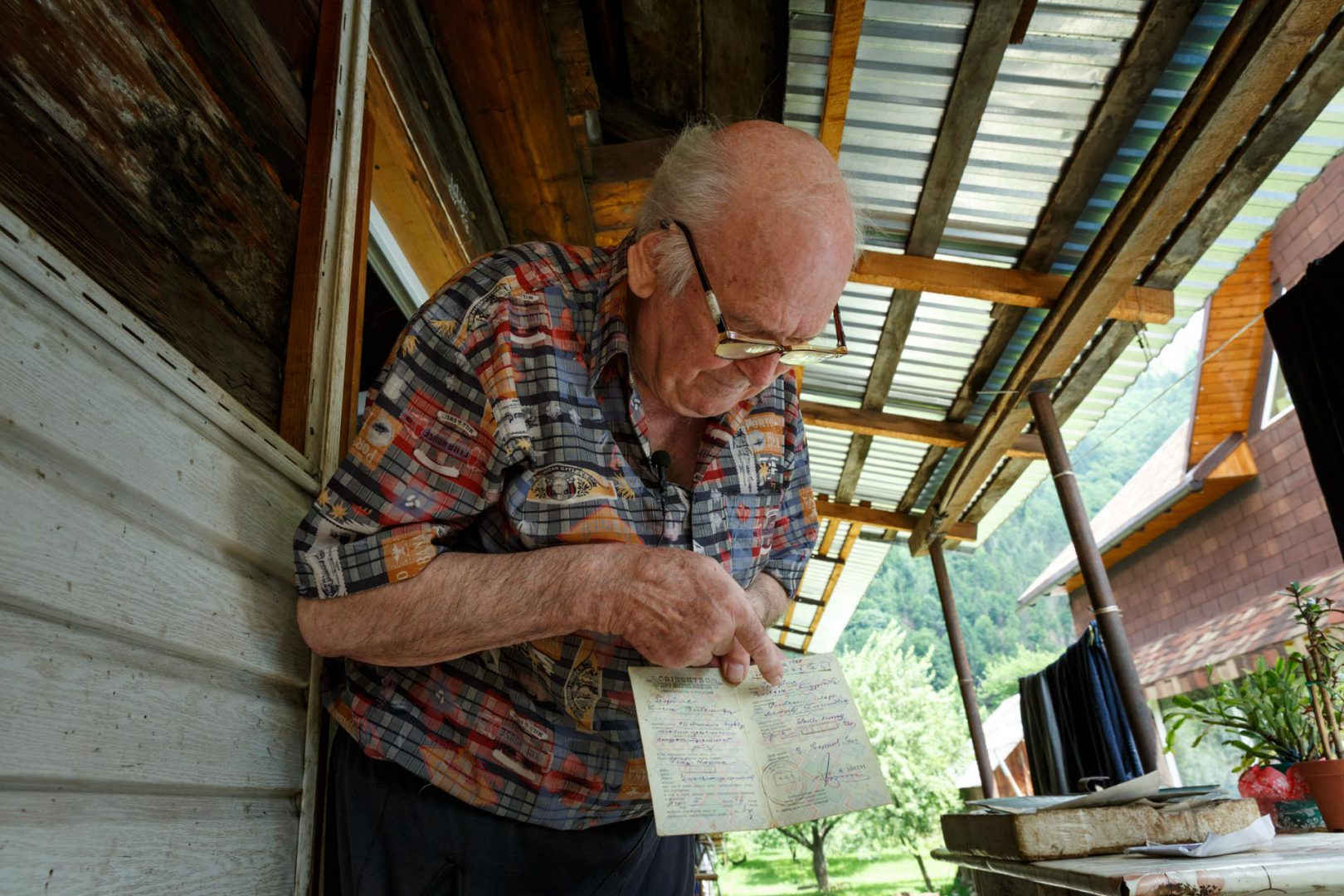

He searches in his home for his birth certificate which states that he has no nationality:

— Look at my certificate. It says here Horbas but there is a dash next to nationality. My parents didn’t have a nationality.

He considers himself a human being, while others consider him a native of Zakarpattia, or a German, or an Austrian.

His lack of nationality is not the only unique feature of his birth certificate. “They also wrote that I am a ‘Vilemovych’ (a patronymic, a second name given to a person in Ukraine, derived from father’s first name). This is not my name, this is the name my father was renamed by.”

The mistake was made after his family returned from Germany in 1948 when they received new documents. As Yosyp says, the reason for the error was that the people handling the documents were barely literate and it was difficult for their colleagues and friends to pronounce the name “Willhelm”. They would say, “Vilem” and so it remained “Vilem Andriyovich”. When they gave Yosyp his passport, he saw that they had registered him as “Yosyp Vilemovych”.

slideshow

Austrians often have worries about their documents because, as Yosyp explained, hardly literate people from the Communist party in charge of them. After forcible displacement, it was essential to prove that they were Austrians. The procedure required finding a person’s official papers in the record office that proved his existence. And only after that the cases of the elderly and the children could be settled as well.

— This process was tricky because according to the papers in the record office I am not Yosyp but Yuzep. I was registered as a Yuzep. I said, ‘As written they won’t give me those documents. They would tell me that I need to go to court.’

Cases like this frequently occurred. People had to go to court to argue that Yuzep and Yosyp were the same person.

In the beginning of the 1990s Austrians from Zakarpattia began to return to Germany in a large migration wave. After the collapse of the road, the local health resort got less and less clients causing a serious blow to the area’s local economy. People sold their homes and never returned. The roads were not adequately kept up so it was difficult to reach Ust-Chorna. Considerable time and dedication was required to improve the roadworks.

When representatives of the Austrian community spoke amongst themselves they would speak in an old Austrian dialect that over time had intermixed with the Zakarpattian dialect. Locals explain that Austrians often laugh at them because they still use words that long ago had become outdated in Austria and were no longer used.

— We speak in our own way, an Austrian dialect that is not clean German. We speak an old Austrian language that German speakers do not understand.

With his children Yosyp Horbas speaks Ukrainian. Long ago, his mother was babysitting his kids. She spoke German and Hungarian and could translate from other languages as well. They used to understand all these languages, but not anymore.

— I already see that I am beginning to forget some words. I don’t have anyone to speak with. Sometimes I forget and mix up my words and I have to think about it. It’s hard for me to express myself. But when I am with German speakers, then I slowly begin to remember.

Yosyp also speaks Ukrainian with his wife. Their children speak Russian with her because his wife is from Russia and has not learned Ukrainian fully yet.

Austrians in Ukraine

Austrians in Zakarpattia are historically emigrants from the Salzkammergut region (an area that stretches eastward from Salzburg across the Alps to the Dachstein Mountains). In the 18th century the Austro-Hungarian Empress Maria Theresa resettled two thousand Austrians along the Marmorosy mountains, particularly along the Ukrainian part of Zakarpattia.

The Austrians set up many logging industries in the region, built up the local infrastructure, and brought with them their culture and traditions. They settled here, built their own buildings and their own churches. These communities survived several waves of emigration. Some left to live abroad, some returned. Out of those who remain here, a majority still get together every Sunday and reminisce about their ancestral memories and the story of what brought them here in the first place.

There are a few versions to the story explaining the resettlement of the Austrians to Zakarpattia. The official version is that Empress Maria Theresa was interested in the Zakarpathian forests and decided to settle Austrians in the region in order to explore the potential for salt, lumber, and other industries in the mountains. In other words, she promised them work. Although there is another version in which the Empress used resettlement as a way to get rid of criminals and other people who displeased her.

The first Austrian colony in Zakarpattia was Deutsch-Mokra (now called Nimetska Mokra but from 1947–2016 the town was called Komsomolsk). They first settled in the village of Dubove and then established Königsfeld (what is now Ust-Chorna). From there they settled the entire Teresva valley.

There is a legend about the original name of the village. Once in a neighboring village called Lopukhove a beautiful girl lived. One day the earl, riding out to go hunting, saw her and immediately fell in love with her. The girl gave him a flower. He raised her eyes to his and told her that the flower looked like a crown, ‘For this reason I will call this field the royal field.” And ever since the field is referred to as “The Royal Field”.

At the end of the war in 1945 the original names of all these areas were renamed by the Soviets. Nimetska Mokra became Komsomolsk and Königsfeld became Ust-Chorna. “Ust” refers to the place where the rivers Brusturianka and Mokrianka meet and flow and “Chorna” refers to the Chornyi Potik stream that runs through the thick forests that always cover the banks in darkness (‘chorna’ means black).

The Austrian Spirit of Zakarpattia

The oldest building in the village is the Roman Catholic church of St. Mary Magdalene. It serves as a center for the Roman Catholic community. Near the altar you can find the engraved coat of arms of the village: five oak leaves. The coat of arms symbolizes the first settlers who came here.

Every Sunday the Church holds both Greek and Roman Catholic services. The Roman Catholic service is conducted in both Ukrainian and German.

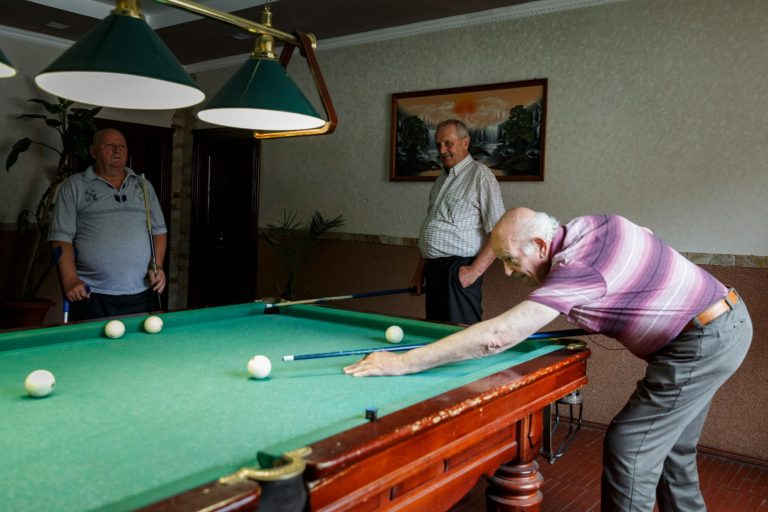

The senior priests conduct the service in literary German. The junior priests speak in Ukrainian. But the native Austrian locals all speak German on Sundays as a custom. It’s one of their few opportunities to be amongst the other Austrian members of the community. Afterwards they go and drink beer and play billiards.

Once the village was considered the prettiest in Zakarpattia due to its beautiful buildings. Unfortunately many of these 200 year old Austrian buildings now stand deserted and abandoned.

The oldest among them are stone buildings where the local authorities used to live. What once constituted the rural council has now become part of the forests again. But you can still identify the buildings by their coat of arms — the five oak leaves.

slideshow

An important part of the house was the chimney. Though they look like Egyptian pyramids they served a purpose. The chimneys were designed to hold a small room where all the smoke was gathered from the stove below, which was used to smoke meat.

The verandas of the houses were picturesque. Flowers were planted and people rested and gathered together to converse. Near every house is a bench, so the village became known for its many benches.

slideshow

Centuries ago, the center of Austrian culture in the town was the restaurant “Edelweiss”. People all the way from Uzhhorod reserved tables at the restaurant a week in advance. The restaurant played live organ music. Even though the golden age of the restaurant has long since passed, grandmothers still go there to drink coffee and grandfathers play billiards.

In earlier times, people all lived according to the same schedule. People worked all Friday, cleaned up their homes on Saturday and on Sunday all gathered together. On Sunday everyone went to Church at 10 o’clock (Kyiv time). After Church everyone went home to have lunch and rested and then at 2 o’clock everyone gathered and sat together outside on the benches.

Traditional holidays. Borys

Celebrating Scheiben is a unique tradition in Zakarpattia. But even the ordinary holidays like New Year or Easter are celebrated differently here. Not all of the traditions for these holidays are still practiced, but they are still interesting.

Borys Spir works as a psychologist at the school in Ust-Chorna. Even though he is not a native, he takes people on tours around the town and can share a lot about it since he knows many stories concerning its history.

— My mom is from Velykyi Breznyi a part of the Carpathians where Slovaks and Ukrainians live together. My father’s family is historically from Novohrad-Volynskyi and my mother is 100% Greek.

Populations and communities were intentionally mixed up and brought in contact with each other as a result of required army service. People from Zakarpattia were sent to Kamchatka and vice versa. This is how Borys came to be born in Petropavlovsk-Kamchatsky.

Borys relates how in school he had a very good German teacher. She taught them proper pronunciation and created an amateur ethnographic club. Students collected various artifacts from around the village for the club.

— We would go to every house where Germans lived. We’d walk everywhere, from the lowlands to the highlands in search of mugs, furniture, money, old paintings, little decorative statues, dishes. From the things we collected we made our own village museum.

Sometime later everything that was collected for their museum was taken to Germany to Gaildorf Karpatenstrasse. In this town now exists the Ust-Chorna museum.

Borys remembers how on St. Sylvester’s Day, a holiday on the eve of New Year’s, boys would remove the gates from the gateposts of homes. The gates were removed as part of a courting tradition. Boys would bring trash on the night of the 31st to a girl’s home and strew it all around the house. They would then wait up and watch if on the 1st of January she would wake up early and clean up the mess, “Will she do it? Will she be a good homemaker? Will she clean it up in time?” If she did, it was a sign that they should court the girl. If she did not clean it up and instead slept in late then it was a sign for the boys that she was not marriage material.

— It was a rural joke. We would remove the gates so the girl couldn’t close them. And then early in the morning people would come by and say, ‘Look how much trash is on the ground everywhere, and she still hasn’t cleaned it up!’

Before Easter there was a custom to make a big bonfire. According to custom, you throw cans of pesticides into the fire. This would make the fire crackle and spark.

— Earlier only the adults and kids above 18 were allowed to join in this tradition. Why? Because earlier we used to throw gas cylinders of all sizes into the fire. The fire would explode and get so big that the windows of the houses would shake.

Connections to Austria

In the village German is the primary foreign language spoken. But every village has their own characteristic vocabulary. So it’s easy to tell if someone is from Lopukhove or Ust-Chorna depending on their pronunciation of certain words.

Every year a group of local kids go to Austria on vacation for two to three weeks. Austrian families host them. These hosting trips are a wonderful opportunity for the children to learn about European lifestyles and practice their German. But before the trip every child must learn at least basic German words and phrases and pass a language test.

In the beginning the kids did not know German and it was a problem for the host families because they could not even communicate about basic things. They had to search for and rely on translators.

— We saw that it was a problem and we set a language requirement as a result. Every child who goes on the trip is supervised and we are in constant telephone contact with them. Every child has their own phone when they go and has a special number we can contact them at.

Every September there is a folk festival in Zakarpattia. Songs are sung, there is entertainment, and people talk. The folk festival is a way for the German speaking minority to get together and mingle. The festival has been in Ust-Chorna, and also has been hosted at the Palanok castle, the Schönborn Castle and other places.

For 18 years an Austrian charity called “One World — Upper Austrian Aid to Fellowmen” has worked in the Tiachiv region. They take care of children in orphanages. On New Year’s Eve they hold an event called “Parcel in a Shoe-Box”. Austrian students pack boxes with items such as pencils, clothes, hygiene products, etc. Some kids even pack cameras or other valuable gifts. After packing, they write whether their box is for a girl or a boy and for what age. These packages are then delivered to schools, kindergartens and rehabilitation centres.

Austrian communities also help support schools in the villages of Nimetska Mokra, Ruska Mokra, Ust-Chorna, and have provided the funding to fully equip the local hospital.