A series of events that led to the appearance of Azerbaijanis in Ukraine is colorful, like a pattern of world-famous Azerbaijani carpets. Service in the Soviet army, student exchanges among universities of the Soviet republics, and then — the First Nagorno-Karabakh War and the first refugees, the collapse of the Soviet Union, the crisis of the ‘90s, and the search for a better life. Today, more than 45,000 Azerbaijanis live in Ukraine, including generations born in an already independent Ukraine. Each of their family histories is like a saga about Azerbaijani traditional culture, which is now intertwined with Ukrainian.

The Azerbaijani community in Ukraine numbers more than 45,000 people and is one of the largest. Isolated contacts between Ukraine and Azerbaijan began in the first decades of the twentieth century, whilst the mass migration process took place during the time of the Soviet Union and after its collapse. In the 1970s, when there was a policy of youth exchange in the Soviet Union, many Azerbaijani students came to study in Ukraine.

The next wave of migration is associated with the First Nagorno-Karabakh War in the late ‘80s — early ‘90s. And the modern wave is, once again, students who arrived here to study. Prior to the beginning of the war in eastern Ukraine, more than 12,000 Azerbaijani students studied at Ukrainian universities. That was the biggest number among foreign students who were studying in Ukraine. Currently this number has decreased and, today, there are a little over seven thousand of them. Those who came from Azerbaijan in search of work in the 1990s already have children who were born in Ukraine or spent most of their childhood here. And they already call themselves Ukrainian Azerbaijanis, though they do not forget about their roots.

Ilhama

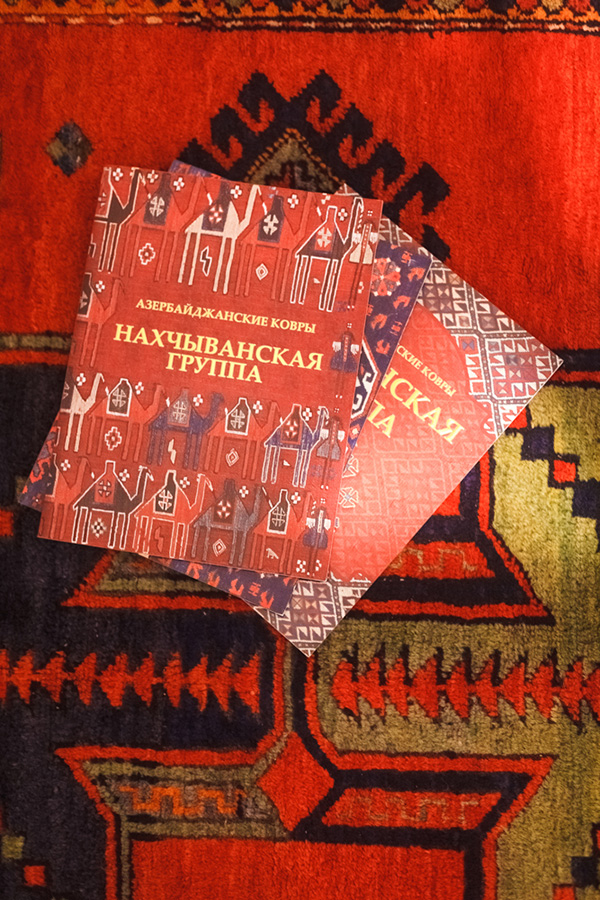

Ilhama has both flags in her home — Ukrainian and Azerbaijani. From her grandmother she inherited a Nakhichevan necklace, from the diaspora — a painted silk kelaghayi scarf (traditional Azerbaijani women’s headdress. — ed.). The cultural code of Azerbaijan lies in those scarves and exquisite woven carpets. Ilhama loves and collects them.

Ilhama Allakhverdiieva, like her three sisters, was born in Ukraine, and her parents — in the Nakhichevan Autonomous Republic, a part of Azerbaijan completely separated from it by Armenian territory. Ilhama’s father is a liquidator of the Chоrnobyl accident. During the Soviet era, he came to the then still young city of Prypiat, which was just being built, to work at the nuclear power plant.

But his first visit to Ukraine happened during his service in the Soviet army. After completing his service, he returned to Azerbaijan for a bit and immediately went to work in Prypiat. However, he returned to his homeland to get married because, according to the Azerbaijani tradition, one should only start a family with other Azerbaijanis. So, Ilhama’s father brought her future mother from Azerbaijan to Ukraine, where the family stayed for good.

After the Chоrnobyl accident at the CNPP in April 1986, Ilhama’s family, like other Prypiat residents, were forced to evacuate from the city. They were lucky, because they had their own car and their father could evacuate his family a little earlier, without waiting for the buses that were supposed to evacuate the citizens of the city. At the time, Ilhama said, they hadn’t yet realized that they would not return home. She remembers that everyone was told that this (departure. — ed.) would only last for a few days and that there would later be an opportunity to return. Nobody understood the scale of the tragedy then. The father took his family to Azerbaijan.

— In the summer, we all went to Azerbaijan and my sisters and I stayed there. I was still young then and it seemed to me that it was just like a summer vacation. But then father returned to Prypiat. We also returned later, but to Kyiv.

In Kyiv, the family was given an apartment in place of the one they left in Prypiat.

In the ’90s, Ilhama recalls, her father did his best for the family not to be in need. In addition to working as a liquidator at the Chоrnobyl nuclear power plant, he was also engaged in wholesale trade.

— Our apartment was like a hotel. Someone was constantly coming here (to Ukraine. — ed.) to earn money: relatives or fellow villagers.

At school, Ilhama repeatedly had to explain what her father was really doing, because her family was treated warily.

— How were Azerbaijanis perceived in the ‘90s? As “The face of Caucasian nationality.” I learned that this is a synonym to people who commit crime and that’s why they (classmates. — ed.) were somewhat afraid of us. Such interesting years, to be honest. Difficult but interesting. I think it was a sort of training.

Upbringing. Concentrated tradition

Ilhama and her sisters were brought up purely in Azerbaijani traditions. In this way, the parents tried to preserve their culture far away from the Motherland. Young Azerbaijanis, says Ilhama Allakhverdiieva, who were born in Ukraine, are a fundamentally different generation from those who moved here.

— My parents moved to Ukraine, and we were already born here. Ukraine is our homeland. This is the difference. Parents raising children outside of Azerbaijan provide more than just traditional Azerbaijani upbringing. They provide a concentrated traditional Azerbaijani upbringing.

As a child, Ilhama recalls, this sometimes caused her to protest, because you live in one environment, and they seem to be trying to impose another environment on you. But when you grow up a little, there comes a time when you need to balance both traditions to understand who you are, what your past is and who you want to be in the future.

So at home there was a family, traditional world, and at school, in the yard, they adapted to other realities.

— We have combined the values from Azerbaijani traditions with the same values from Ukrainian traditions. We are very open in our relations with neighbors, friends, and others that we know — in the yard, at school, at university, so there were no barriers.

Every people has a close connection with its homeland. Azerbaijanis are no exception. Even those who were not born there feel this connection.

— When I am in Azerbaijan: in Baku, or, especially, in Nakhichevan, I feel awe for that land and for what I see. I love everything there. You are now an adult and you perceive it differently, these are your roots, your blood. It seems to me that this feeling is genetically transmitted.

Azerbaijani Youth Union. Cultural diplomacy

In 2010, while studying at the Faculty of History of the Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv, Ilhama and a few of her university friends founded a youth organization — the Union of Azerbaijani Youth in Ukraine (UAYU).

At that time, it was the first Azerbaijani youth organization in Ukraine. During the All-Ukrainian Forum of Azerbaijani Youth in Dnipro, a decision was made to establish a coordination council of Azerbaijani youth in Ukraine. The Kyiv delegation returned to Kyiv and decided that this was a historic moment, an opportunity for young people to unite in the community.

— We are the ones who started this movement and were able to unite amazing Azerbaijani girls and boys around UAYU. Even those who had previously stayed away from public activities joined our organization.

UAYU, Ilhama says, was created primarily to unite Azerbaijani youth living in different regions of Ukraine. This also applies to students who come from Azerbaijan to Ukraine today to obtain higher education. The union aims for cultural exchange between the two nations. In particular, it constantly organizes exhibitions of Azerbaijani art and concerts of Azerbaijani artists, holds meetings and round tables with Ukrainian and Azerbaijani public and cultural figures.

— The Union forms a connection between Ukraine and Azerbaijan, between the youth, between the nations. The core of all our projects is cultural diplomacy.

Those who live in Ukraine can share their domestic and cultural experiences with those who have just arrived. And those who arrived recently talk about modern Azerbaijan.

slideshow

— This is important now because those who grew up in the ‘90s have experience with a certain information vacuum. They communicated only with their family – their, so to say, mini-republic. They still do not have a complete understanding of Azerbaijan and only know things that are specific to the area or family which they come from.

Ilhama’s interest in public activities related to the diaspora is common for her family.

— My father was an activist of the diaspora movement in the ‘90s, when it was just beginning, when organizations were created, when the structuring of the Azerbaijani diaspora had already begun.

Ukrainian Azerbaijanis, according to Ilhama, were the first Azerbaijanis in the world to be structured into an organization. Later, the Ukrainian experience was adopted by Azerbaijani communities in other countries of the world and large-scale formation of organizations began.

Ilhama was a part of these movements since childhood, so it is only natural that she chose the path of a public figure. However, in her homeland, her choice would be condemned rather than supported. The reason for this is, sometimes, excessive conservatism of traditions.

To be an Azerbaijani public figure

Azerbaijani society is patriarchal. Being a female public figure in Azerbaijan is an innovation even today. Proactive women, Ilhama says, are currently a minority, and attitudes toward them are mixed. According to the traditional ideas of Azerbaijanis, a woman should not have an active position in society. Often, her main role is to take care of the family and the children. Even better — several children. Arranged marriages and large families are still part of the norm in this culture.

— I once held an event for the Azerbaijani diaspora in Ukraine. My father, so conservative, then said, “Did you do it?” I replied, “Yes.” And he then said, “Well, that’s all, do not do it again.”

Her father, Ilhama explains, doubted neither her abilities, nor her. He doubted how her initiative would be perceived by men from their community.

There are a lot of girls in the Union. But at meetings of diaspora leaders, Ilhama admits, she is usually the only woman. She talks about a situation when one of the leaders sharply condemned the fact that she was elected as a head of a work group at one of these meetings. He was assuming that one girl can not manage ten men.

— Many girls wrote to me that I am their role model because they now see that an Azerbaijani woman can be an active public figure. I understand that this is very, very important if it can change the picture. It is already changing it!

So, at first, Ilhama was the only woman in the Union of Azerbaijani Youth in Ukraine, but very soon the situation shifted, and currently there are almost more women than men.

One of the undertakings of UAYU is to encourage the study of the Azerbaijani language. There are now Sunday schools in Kyiv and other cities of Ukraine, where children can study Azerbaijani language, history, dances, and songs. These are mostly Azerbaijani children whose parents want them to know the language. Language courses are also available in the Union from time to time. Azerbaijanis are not the only ones who want to join these courses.

— When launching the courses, we thought that our audience was Azerbaijanis, and several Azerbaijanis came to us, but the rest were Ukrainians. We were really curious why Ukrainians were choosing the Azerbaijani language. It turned out that it was either the wives of Azerbaijanis who wanted to join the culture, or employees of Azerbaijani companies. Even representatives of our Ministry of Foreign Affairs attended these courses.

Ilhama knows Azerbaijani well, because she listened to her mother tongue since childhood, and grew up in a family where they spoke mostly Azerbaijani. But even she is constantly improving her language skills. For her, Azerbaijani and Ukrainian are the main spoken languages at work. She communicates with her sisters mostly in Russian, and with her parents in a mix of Azerbaijani and Russian.

— I once set a goal for myself: to become fluent in Azerbaijani, so I could use it in everyday life. I decided to study and improve the Azerbaijani language so that I could freely express my thoughts in it, as well as in Ukrainian. I am still in the process of doing this, but if we compare, the quality of my Azerbaijani language has improved.

Growing up in Ukraine, Ilhama has always been concerned about the socio-political processes and events that the country has experienced at different times and is experiencing today. Ilhama was in Azerbaijan during the Orange Revolution of 2004 — 2005. She remembers that when she came back to Ukraine, she found only a tent camp on Khreshchatyk.

— However, during the Revolution of Dignity I was here and, to be honest, I had a hard time with this moment. It was not clear what was happening. You seem to understand what people stand for: for the opportunity to live with dignity, for the opportunity to follow the European path of development for the country, but I had mixed thoughts. The moment that put an end to all the thoughts that I had about the Maidan, was, of course, the shootings of activists in late February 2014.

— I have no dilemma about self-identification. I identify myself as an Azerbaijani and also as a citizen of Ukraine. It seems to me that I can consider myself an active citizen of Ukraine, because I am very concerned about the fate of my nation, my country.

slideshow

Azerbaijan and Ukraine

Active contact between Ukraine and Azerbaijan started in the early twentieth century. During the period when the territories of present-day Ukraine and Azerbaijan were part of the Russian Empire, a large number of Azerbaijani youth studied at the universities of the largest Ukrainian cities — Kyiv, Odesa, Kharkiv.

Azerbaijani Yusif Vezir Chemenzeminli entered the Faculty of Law of the Imperial University of St. Vladimir in Kyiv in 1910. He later became the ambassador of the newly formed Azerbaijan Democratic Republic to the Ukrainian People’s Republic and was one of the first Azerbaijani diplomats to officially represent the newly formed state abroad.

With his assistance and initiative, literature evenings were held and articles on the culture and economy of the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic were published in periodicals.

But the first notable migration processes from Azerbaijan to Ukraine took place during the Soviet era. Many Azerbaijanis fought in the Soviet army during World War II. A fairly large wave of migration occurred during the collapse of the Soviet Union and the first clashes between Azerbaijan and Armenia over the territory of Nagorno-Karabakh, which were called the First Nagorno-Karabakh War. Some Azerbaijanis then received refugee status in Ukraine.

Also, thousands of Azerbaijanis came to the already independent Ukraine in search of work in the early ‘90s and stayed here. Gradually, the Azerbaijani community in Ukraine grew from 4,000 to more than 45,000 people.

Azad

Journalist Azad Safarov was born in Azerbaijan and lived there until 1994. Azad’s parents belong to the wave of migration whose representatives came to Ukraine in the ‘90s, looking for work. First, his father went to Russia, opened a private enterprise, and began trading.

— He traveled back and forth, brought goods and sold those in Azerbaijan and after he went back to Moscow, all relatives asked if they could come along, to be shown how to do it. He was never a businessman, but he was trying to do something. Then he came to Ukraine, to Donetsk, and he liked it there.

In Donetsk, Azad recalls from his father’s stories, newcomers were treated quite well then. So the father stayed there to work in sales, opened several kiosks, and later helped his family to join him there. Little Azad and his mother arrived in 1994.

— The first thing I remember is ice cream. The best ice cream in the world was in Donetsk. We bought eight or nine cups of ice cream in one day. I ate almost all of it myself, and it was a really cool experience because it was the first time that I understood the importance of a product’s quality. Ukrainians believed that there were no quality products in Ukraine at that time. For us, after the ice cream I ate in Baku, it was just amazing.

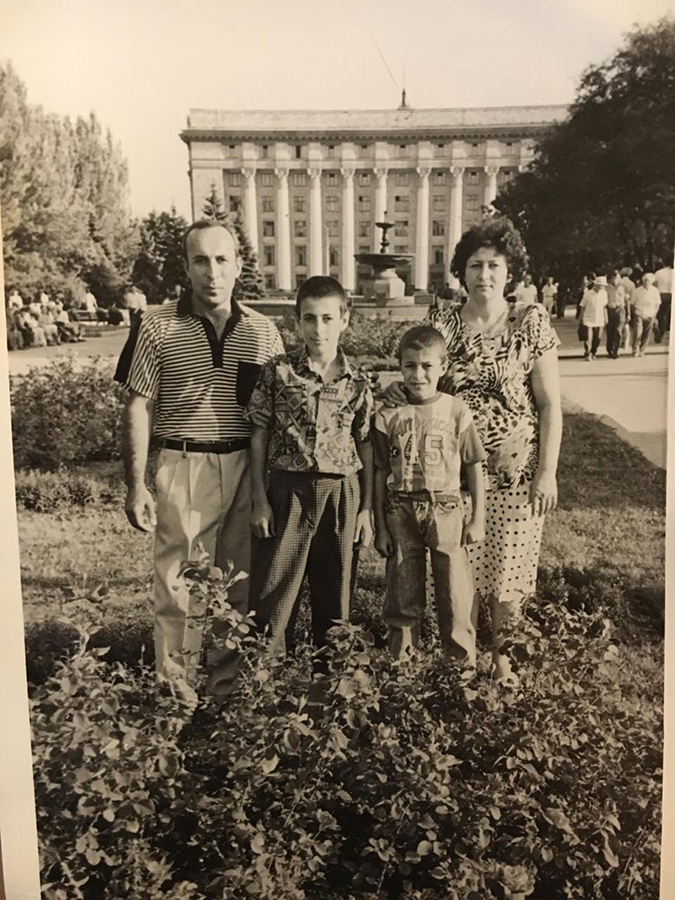

Family of Azad Safarov. Donetsk, 1995.

Azad has very vivid memories of his first visit to Ukraine.

— We drove for a very long time. Arrived at the airport, landed in Lugansk, it was almost the New Year. My mother took a cauldron of pilaf with her, because everyone understood that we will celebrate the New Year somewhere along the way.

Azad’s father arranged with the airport staff to give them and their mother a separate room where they spent the night, ate a New Year’s cauldron of pilaf, and went to Donetsk. They were on the road for the entire day despite the relatively short distance. Since then, Azad and his parents have lived in Donetsk for 15 years.

Azad worked from an early age, helping his parents with the trade. At the age of eight, he and his father tallied up the money they earned at the end of each work day.

— My father taught me to take a notebook and write down, daily, how much was sold, how much was left, and I counted this there. For example, in the evening, my dad would come from work, put the money in front of me and say — tally it up. It was difficult for them, understandably, but my father was a very charismatic person, he had a lot of friends, he found these friends very quickly. When he walked down the street, everyone greeted him and he always told me, “Here I paid off a debt of this much money; that’s where they owe me this much money.” He was a very good man.

Relatives from Baku, Azad recalls, often asked their father to help them move to Ukraine. He helped many move and start their own business in a new place.

— We sold in the city garden of Donetsk. Now this place is called the Golden Ring. And, in fact, the first one to put up a chair and start selling in that place was my dad. After that, everyone started doing it there. My parents were in favor of me understanding the value of work and getting used to it from childhood. For example, when I wanted a TV, he said, “Okay, if you make enough money for it during the summer, we’ll buy it for you”. And I really earned it myself, worked hard, and only then did they buy it for me.

After his father’s death, Azad’s mother moved back to Baku.

When men dance

Dance is a passionate hobby of Azerbaijani men. Azad’s father always wanted him to learn to dance. He would always put the money somewhere in plain sight and would set a condition: “If, by the evening you memorize this move, you can take the money.” If I memorized, I was able to take the money. If I had it poorly memorized, I was allowed to take only the half, and the rest I could get only when I had everything memorized.

— In Baku, dancing for men is a fetish, it is very important. They may be modest in life, but not in dancing. It’s very cool when men dance, especially boys. When I went to Baku for a wedding, everyone knew that I could dance, and everyone asked me to go out and dance.

Azad and his mother. Donetsk, 1997.

Azad repeatedly participated in a kind of dance battle of traditional Azerbaijani dances at weddings and other celebrations. And he was always the winner because he could dance longer and more energetically than others.

— Sometimes, when guests would ask me to dance, we would bargain for how much they would pay if I danced. Yes, it was already kind of a tradition and my father really liked it. Since then, I have learned to dance, and when I go to Azerbaijan now, and everyone invites me to dance, I say — no, no, I can’t, I’m old, please, no need.

Azad’s parents kept their children close to them as much as possible. Mostly because they feared negative treatment toward them as migrants.

— Many of our relatives and acquaintances went to Moscow to work, and distressing things happened to them: they were persecuted, beaten, attacked. But this was not the case in Ukraine. However, our parents were still afraid; they thought that Donetsk was like Moscow. That’s why they always wanted their children to be near them.

Azad’s fate, as a true Azerbaijani, was determined in advance by all his relatives — he should certainly have married a Muslim woman, an Azerbaijani. Although now Azad is no longer asked about marriage, it used to be a major topic of discussion among relatives.

— If you take a very traditional family and multiply it by 10, and multiply it by another 100, the result will be my family. According to Azerbaijani traditions, I am too old: I should have had married at the age of 21; at the age of 24, I should have had three children; at the age of 25, I should have had an apartment; at the age of 26, I would have had to do repair work in the apartment for the third time and have two cars, and I should have had boasted about it.

Azad admits that such direct interference of the family in his personal life is one of the main reasons why it is difficult for him to communicate with relatives in Azerbaijan. He has lived most of his life in Ukraine, where other notions of freedom of choice have long prevailed in everyone’s life.

The next postulate that Azerbaijanis must adhere to is total respect for parents and obedience, says Azad.

— If you obey your parents — you are good, if you do not obey — they say “you became Russian.” That is, in the ‘90s, no one in Azerbaijan said “Ukraine” at all, everyone said: “You went to Russia.” In other words, they did not even understand what Ukraine was. It was only then, after the Revolution of Dignity, that they realized that “Oh, this is Ukraine, this is separate from Russia. This is not Russia”. Well, it’s good that they are actually saying that. Let them talk about the Russians. “Russian,” for them, means that you are disobedient, you are already promiscuous, you have already assimilated, you have already forgotten your roots, and other things like that.

Nevertheless, Azad is proud of his Azerbaijani origins and sees his growing up in conservative Azerbaijani traditions as a valuable experience rather than a burden. He says he likes to be half Azerbaijani and think as one, as well as to be and think like a half-Ukrainian.

— The most important thing that my nation has given me is the ability to always stay positive. We even have songs that are called “mugan” — they are very sad at the beginning, but then they suddenly transition into dance. This is the mentality: no matter how bad it is, stay positive. It helps me a lot.

slideshow

Ukrainian East. Voices of Children

Azad is a professional journalist, photographer, and videographer. But since the start of the war in eastern Ukraine, he has spent most of his time working for the charitable foundation “Voices of Children,” which helps children who were hurt, in one way or another, by the combat and are living alongside the war.

The organization was started by activist Olena Rozvadovska, who has been volunteering in the East since 2015. Currently, the Voices of Children charitable foundation provides art therapy for children, supports and counsels families with children living in the war zone, and advocates for children’s rights. The foundation’s headquarters are located in Sloviansk and communication teams are located in Kyiv and Bonn (Germany). Azad often travels to the East, converses, and films stories about local children.

— It is important for us to get to know these children. We do not stay far from them; rather, we travel, communicate with them and know them personally.

In 2014, Azad Safarov began traveling to the East as a Channel 5 journalist. He later began collaborating with foreign directors who made videos about the Russian-Ukrainian war. He worked with director Simon Lehren Wilmont on the film “The Distant Barking of Dogs”.

— While making this film, you realize that you don’t just want to come, film and leave, and get a festival award, but that you want to change something.

Work is underway on the next film about the impact of the war on the socio-economic level. Together with the director and the film crew, Azad visits and films orphanages in the war zone.

slideshow

For Azad, being a Ukrainian journalist in the war zone in Donbas meant working undercover all the time. He changed his name and could film there only because he had a Donetsk residence permit.

—The last time, I left Donetsk in the trunk of a car. We were going to Donetsk, spending the night in the field, when the MH17 plane crashed. We were the first to get there. They stopped the car and told me that the security service of the terrorists from the territories of Eastern Ukraine temporarily occupied by the Russian Federation found out that I was the same Safarov working for “Channel 5” and wanted to interrogate me. I said, “Yes, everything will be fine”, to which they replied, “No, we don’t work like that, we can’t do that.” My colleagues, foreign journalists, found a car and asked me to get in it. And the minute we left, I opened the trunk and saw the Ukrainian flag, only then I felt relieved. And I realized that this is it, I am now banned from there because I worked for “Channel 5,” and they knew what kind of channel it was. And it is clear that if I was caught, I would have “enjoyed” the views of a basement, likely for a long time.

Now Azad can no longer get to Donetsk, where he grew up and where his parents’ apartment still remains.

— When Donetsk is Ukrainian again, and I am sure that it will be one day, I would like to go look at the places where I lived. Because now I treat Donbas much differently. When I grew up, I realized how many amazing people there were, and how completely different the mentality was from what I thought. I just didn’t notice these people growing up.

To be a Ukrainian Azerbaijani

Because of the secluded environment of communication in which Azad grew up, because of his parents’ fear of being different, not like everyone else, the boy seldom spoke with peers. He never went to summer camp. The parents did not let him. Again, they were afraid that their son would be bullied there.

— For some time I had a hang-up that it was not always necessary to say that I am Azerbaijani. It was only later that I understood that this is my uniqueness — to be an Azerbaijani in Ukraine. And we need to talk about it. On the contrary, this is such a great mix of Ukrainian and Azerbaijani. I thought a little differently, acted a little differently than my classmates. And since then, from the 8th or 9th grade, I have always highlighted that I am Azerbaijani.

After studying at the university, Azad came to Kyiv for an internship in the OSCE. At the University of Donetsk, he told his classmates a lot about Azerbaijan. He was the only Azerbaijani in the class. He set a goal to live and work in Kyiv after studying. And he achieved that goal. After some time.

— I fell in love with Kyiv. I told myself that I would do anything to get back here.

Before I did, there were long negotiations with family to be allowed to move to Kyiv. They were all against this idea. They were all saying that I am being foolish. They claimed that I did not know the land, and that I did not understand anything there. Convincing relatives, breaking away from the family, and starting my own life was a great challenge, admits Azad.

— I really wanted to come here because I liked the pro-European and pro-Ukrainian position of Kyiv. And when I first arrived here, I saw young people sitting on the pavement and listening to music. I was in awe! Because I have never seen such a thing in Donetsk or Baku. Then I swore — I would return to Kyiv.

— When I arrived in Kyiv, it was like a fresh start for me, because I came with essentially one suitcase. I did not know where to go. I just came and thought: now I’ll go to the editorial office — to television. I went, I believe, to “Inter” then, and I was told that I needed to send my resume. I was shocked: “What resume? I am already here, hire me!” To which they answered: “No, you need a resume!” I came to Khreshchatyk week after week and waited for someone to answer me. I was thinking in my head: I’ll come back to Donetsk, if nothing works out for me, I’ll lock myself in the bedroom, I won’t come out, because I lost.

For an Azerbaijani, if you want to be a journalist it means that you can only be a TV reporter, Azad says. So, following family rules, he only wanted to work on television. But before his work on “Channel 5”, Azad also worked as a correspondent for print media.

— I accidentally saw an ad in the newspaper for another newspaper “Arguments and Facts”. I called in and said: “Do you need young and energetic people to join your team?”. And the editor was like, “Mmm… sure!”. So I said: “Well, I’m coming to you now!”. I arrived, started to take out my diplomas from the bag. That is when the editor said: “Hold on, hold on. Just tell me about yourself.” And then they hired me.

slideshow

Later, Azad went to work in Germany, in the Ukrainian editorial office of the “Deutsche Welle.” He worked there for five years and is now a freelancer for various international organizations.

— I came a long way to receive Ukrainian citizenship. For me it was very fundamental and very important. I never had Azerbaijani citizenship because I moved to Ukraine when I was eight years old and I did not have a passport then. For a very long time, I was a stateless person and when I first came to the Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine to film, the guards said: “We can’t let you in, you don’t have Ukrainian citizenship!”.

In Ukraine, Azad learned Ukrainian, as well as Russian, from scratch. When they moved to Donetsk, he went to the 5th grade. He recalls that everyone there spoke Russian then and classes were taught in Russian as well. And he did not know a word of Russian.

— When I was sitting at the first desk and the teacher said: “We open the brackets, we write this, this…”. I understood her literally, so I wrote: “We open the brackets…”. That is, I did not know what that meant, and did not understand anything at the beginning, so I was sent to a tutor.

The teacher who taught Azad Russian at first was in love with the Ukrainian language. When she saw the student’s interest, she quickly switched to Ukrainian lessons.

— I remember an incident: another girl came to her with her mother, and, at one point, that girl’s mother said: “Well I wouldn’t even teach my child the Ukrainian language — it’s the language of Khokhols”. And this teacher, she was about 70 years old, asked the girl to go to the kitchen and told her mother: “Take your daughter and never come back here”. Because she loved the Ukrainian language very much, she respected it very much. And I stayed. She was pleased that an Azerbaijani came to learn the Ukrainian language.

Azad’s family speaks Azerbaijani and Russian. Azad now practices Azerbaijani less often than Ukrainian.

— When I came to “Channel 5” my future boss asked me: “Do you know the Ukrainian language?” I said: “Of course!”. But I didn’t know anything, I couldn’t say anything, and I think he understood that.

After a few months of working on television, Azad began to study Ukrainian intensively.

Azad was quickly taught to speak Ukrainian by his then-girlfriend. They talked, did exercises, listened to Ukrainian content. Now he can tell Ukrainians about Azerbaijan in sophisticated Ukrainian.

— You cannot live in a foreign country and not know the language. But then, because there were times when few people spoke Ukrainian, this was impossible. Now, when people say: “Wow, you have such a beautiful Ukrainian language!”, I’m very surprised, because it’s absolutely normal for me. Well, first of all, I’ve lived here for a long time. Secondly, I am no longer a guest in this country. I have Ukrainian citizenship. How can I not know the Ukrainian language. No matter where I came from.

supported by

Material prepared with support of United States Agency for International Development (USAID)