The Ukrainian company BIOsens developed a mobile analyser that quickly and precisely detects toxic compounds called mycotoxins in crops. This device prevents our favourite corn cookies from having carcinogenic compounds, allows farmers and traders to avoid additional expenses, and saves the environment from excessive CO2 emissions.

Mycotoxins in food can cause acute poisoning. However, the main danger is in the cumulative effects and constant impact of toxins on a body, which, according to the World Health Organization (WHO), can lead to the progression of immunodeficiency and cancer in humans and animals. If permissible levels of mycotoxins in food products are exceeded, such products must be disposed of, which means enormous losses for the agricultural companies and traders. It also means significant greenhouse gas emissions during the cultivation, transportation, and destruction of spoiled raw materials. Therefore, early and prompt diagnostics will help prevent a large loss of resources.

Mycotoxins

Mycotoxins are the toxic compounds produced by lower fungi (in everyday life they are called molds). There are more than 500 species of mycotoxins that are often found in crops and can appear on them during cultivation or storage. Mycotoxins are most often found in cereals (corn, wheat, and rice), oilseeds and legumes (peanuts, soybeans, sunflowers), spices (chili peppers, coriander, turmeric, ginger), and nuts.

The levels of mycotoxins are an important criterion for assessing the quality of agricultural products and food. The WHO and the UN have been researching these substances and ways to deal with them for decades. Here are clearly defined standards for the permissible levels of mycotoxins in agricultural products both abroad and in Ukraine. In Ukraine, compliance with these standards is monitored by Derzhspozhyvstandart (the State Committee of Ukraine for Technical Regulation and Consumer Policy). In infant foods, for instance, mycotoxins should not be present at all. The content of aflatoxin, which is the most carcinogenic mycotoxin, should not exceed 4 nanograms per milligram in food products and can only range from 4 to 10 nanograms per milligram in animal feed.

The WHO advises the average consumer to choose the freshest possible products (groats, nuts, dried fruits) and avoid those that are moldy, dry, or damaged. One of the reasons why there are no instructions on how to get rid of these compounds in food is the difficulty of destroying them. They cannot just be washed off with water. In addition, mycotoxins are very resistant to high temperatures. Chemical processing is also not the best option, as chemicals have a negative effect on health.

Such compounds can enter the human body when a person consumes bread, nuts, cereals, groats, or even wine and beer made from contaminated raw materials, or animal products, if the animal feed contained mycotoxins. In this case, food contaminated with mycotoxins cannot always be distinguished visually. The presence of mycotoxins may be indicated, for example, by mold on bread. However, it does not always mean that the bread is contaminated. Similarly, toxic substances may not affect the appearance of the product at all. According to various estimates and world studies, from 60% to 80% of the products analysed were affected by mycotoxins, and about 20% of this score violates the norms prescribed by the EU legislation and UN documents.

The active growth of molds is caused by high humidity and excessive carbon dioxide emissions into the atmosphere. Global climate change and rising average annual temperatures also provoke more active fungal growth, increasing the risk of spreading toxins. This trend is confirmed by scientists from the European Food Safety Authority.

The increase in the amount of mycotoxins in products leads to large economic losses in the agricultural sector. If the level of damage is too high, cereals or other crops can be used as a basis for biofuels, as contamination by mycotoxins does not interfere with methane production. But in the end, all these methods require additional financial costs, including the transportation of raw materials for recycling, which at the same time increases CO2 emissions into the environment.

BIOsens mobile analyser

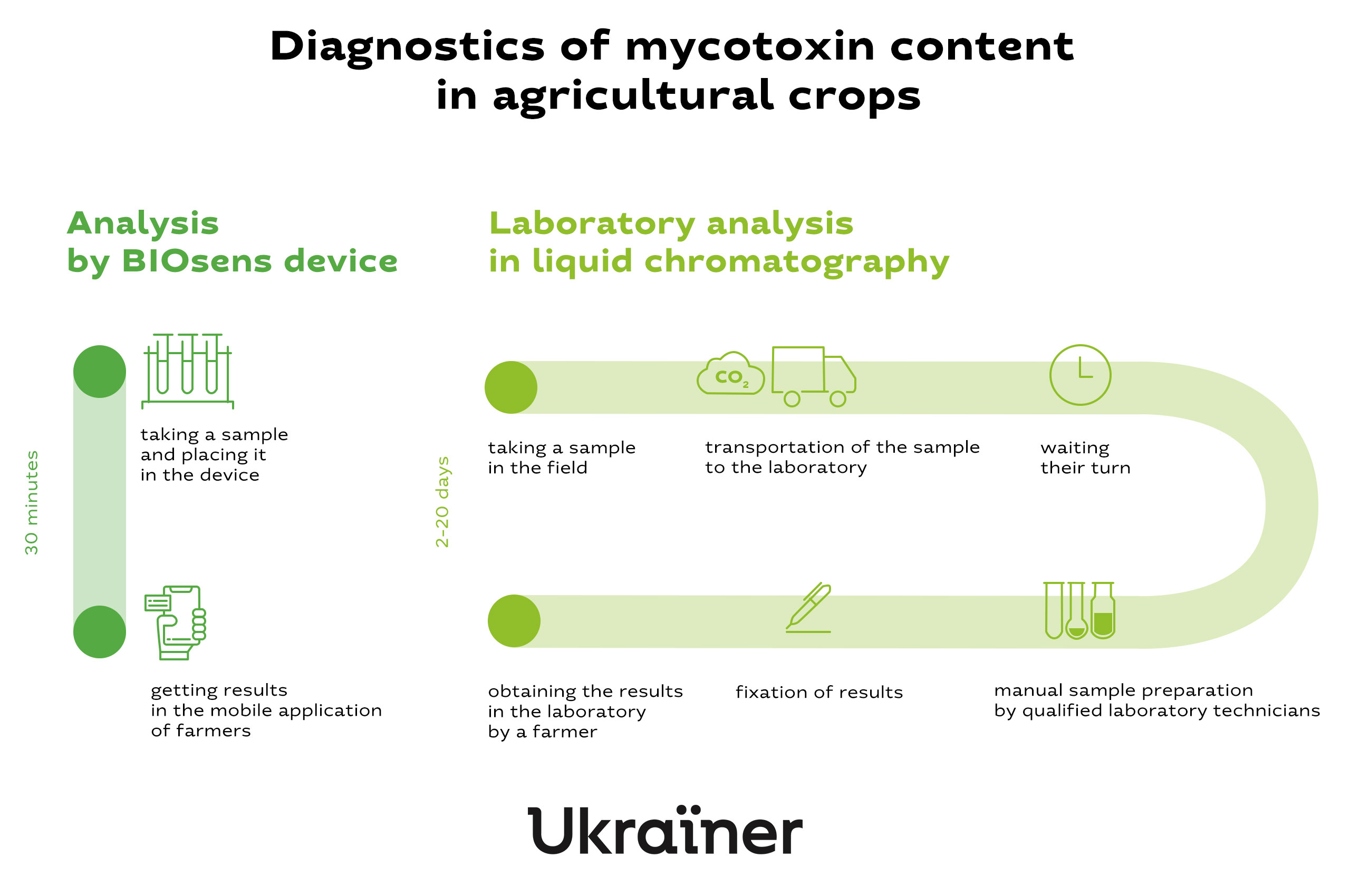

Today, you can test the product for mycotoxins in two ways: in a laboratory or by rapid diagnostics. The latter method has a number of advantages over laboratory tests, the most important of which is significant time savings.

The Ukrainian company BIOsens has developed a device for rapid diagnostics of mycotoxins, thus providing farmers and food producers with quick access to information about products safety. The device enables the analysis of corn grain for the content of the most common mycotoxins, aflatoxins B1 and ochratoxins. The developers of the device also plan to analyse wheat, peanuts, and a number of other crops.

The CEO and founder of the company Andrii Karpiuk recounts that the foremost advantage of the BIOsens device is the efficiency of the analysis.

“To perform diagnostics, you usually need to send crops to the laboratory, which is expensive (laboratory analysis is about 20% more expensive than rapid testing) and long. We make a device that can perform this analysis for half an hour in the field.”

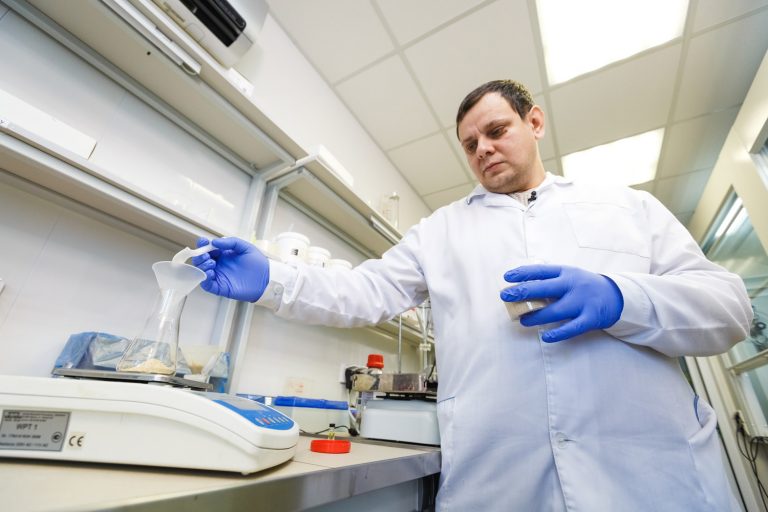

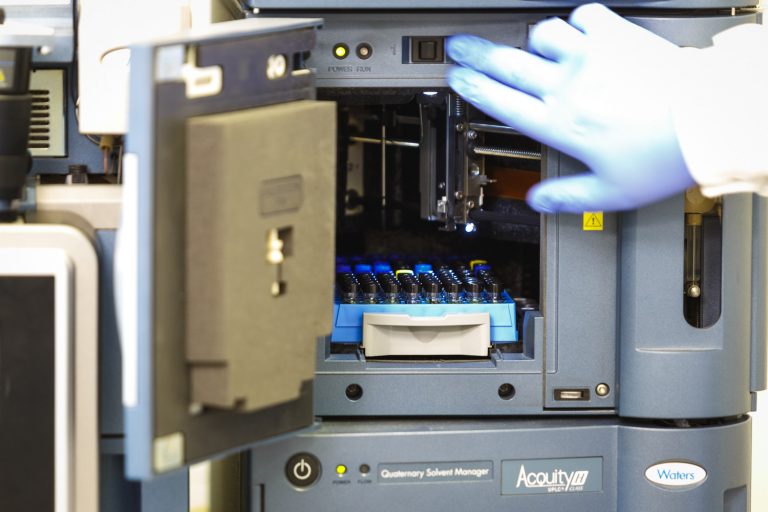

One of the core methods in laboratory testing of mycotoxins is chromatography. With the help of the analysis in the liquid chromatograph, it is possible to detect the presence of toxins, pesticides, antibiotics, and other harmful substances in food. Sample preparation for the chromatograph is performed manually. After that, the flasks with the product samples are placed in the autosampler of the device, where the analysis takes place for about 6 hours.

This method requires stationary equipment, as well as additional time for sample intake and delivery to the laboratory, which entails transportation costs. In addition, laboratories test products in a queue mode. Therefore, total testing for mycotoxins may take from 3 to 20 days.

“Chromatographic analysis takes about 6 hours, and rapid diagnostics (test strips or ELISA) takes from 45 minutes to 2 hours. However, the time of sample delivery to the laboratory is from several days to several weeks. With our device the farmer has an opportunity to carry out the analysis on-site and receive results within 30 minutes. And you don’t have to go anywhere for that.”

The rapid detection methods currently present on the market have a quite large measurement error, from 40% to 50%, and this is one of their main disadvantages. The error of the BioSens analyser is currently about 35%, while in liquid chromatographs worth hundreds of thousands of dollars it is about 5-7%.

“Our customers say they are ready to buy the device in case the error is in the range of 10-15%. So the main challenge for us is to reduce the error from 35% to 10%. This is what we are working on now.”

The market for rapid tests is developing swiftly, and BIOsens already has competitors there. However, Andrii highlights an important advantage of their analyser, namely the full automation of the process. Most of the available devices are smaller and cheaper. But they require additional conditions at the stage of sample preparation for the analysis. This often means the need for additional equipment. BIOsens works completely independently.

“We reduce the influence of the human factor on the analysis. After all, if you make any incorrect manipulations with the reagents, with the contents when preparing samples, you can get the wrong result. In addition, it is also one common system that syncs with the mobile application and web service. Therefore, if we talk about the analyser with automated sample preparation, there are no analogues in the world.”

slideshow

Untimely detection of mycotoxins leads to additional costs at different stages of production, transportation, and disposal of infected grain. It also has the effect of increasing carbon emissions and, consequently, global climate change. Andrii Karpiuk explains how the BIOsens analyser can help with this:

“Our device can perform about 300 tests a year. One trip from the field to the laboratory is about 2.5 kg of CO2 emissions. Avoiding 100 such trips using our field analysis method means avoiding emissions of 250 kg of carbon dioxide.”

CO2 emissions occur through the sample logistics, starting with sending samples to the laboratory and ending with large tankers that export products. If the product is contaminated, there is a border rejection procedure, which means refusal of entry into the importing country.

“If a tanker arrived with dozens or hundreds of thousands of tons of grain and the border rejection procedure took place, one should consider: either take it to a country where the procedure is less strict or dispose of it completely On the one hand, these are huge financial losses, on the other, significant amounts of CO2 emissions from fuel combustion on these tankers. And the amount of CO2 that was used to grow these tons of grain was essentially exploited needlessly because in the end these products were disposed of.”

The device can also reduce the harmful effects of pesticides (including fungicides that counter molds) on the environment. And at the same time, it reduces the costs of farmers to cultivate fields. At the stage of storage of cereals and feed, some farmers may also add special sorbents. They reduce the harmful effects of pesticides on animals. But sorbents are expensive, and for many an easier solution is to analyse the feed and not give the infected to animals.

“If mycotoxins are diagnosed at the early stages, then, accordingly, it will not be necessary to use much of this sorbent. It saves resources. Similarly, if we understand at the early stages, such as during the growing season and during cultivation, where fungi and, consequently, mycotoxins develop, we can use fungicides more precisely. It respectively reduces the load on nature, on the ground.”

How the device works

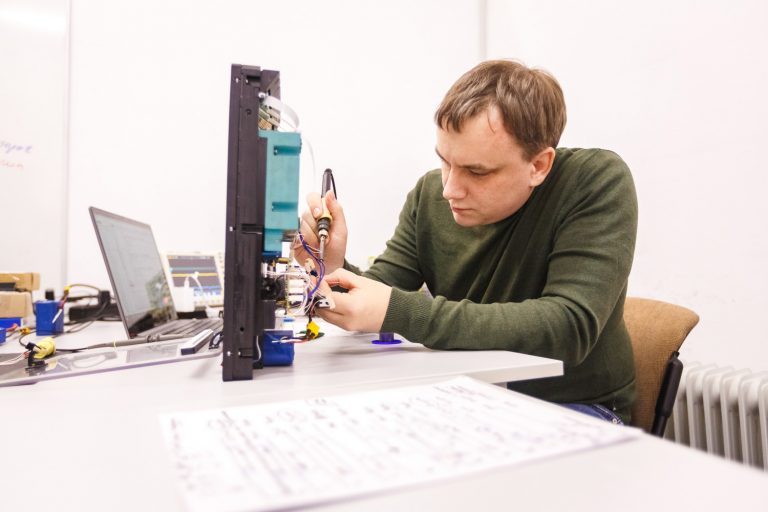

From 2016 until today, the company has developed several prototypes of the device. During this period, the analyser has evolved significantly, says BIOsens founder Andrii Karpiuk:

“In the field, it is difficult to conduct a qualitative analysis of mycotoxins. Then we realised that we needed to automate sample preparation. As a result, we made a prototype on a 3D printer that automates sample preparation using a cartridge that we patented. While working on this prototype, we changed the sensor itself.”

To perform BIOsens analysis, you need: an analysis device, a cartridge, a mobile application and a web service with a user’s personal account.

“We are constantly working on five areas: biochemical (cartridges and sample preparation), mechanical (boards, engines, parts), electronic (software), mobile application, and web services. One to three people work in each area.”

slideshow

The BIOsens team develops the device on their own, but they have partners in the laboratories with whom they conduct joint research. Some of the tests are done on a chromatograph to compare the results with their device. In this way, the team receives information on what needs to be improved and strengthened.

To perform the analysis, you must first prepare a sample: grind corn, take 2 g and fill it into the cartridge. After that the cartridge is inserted into the device. Then the process is automated: the device performs sample preparation and analysis, which also consists of several stages.

The task of sample preparation is to make an extract from corn. The grain is weighed, ground, filtered, made into an extract, and the required reagent is washed out. The sample should be filled into the cartridge, and the cartridge then inserted into the device. After that, the user receives the results of the mycotoxin content on the screen in 30 minutes. The same results will appear in the user’s personal account in the mobile application. The web service stores test results, as well as sections by time intervals and various samples. This allows you to analyse the results over a certain period and, accordingly, to make forecasts.

The device has a scale with 4 levels of mycotoxin content in cereals that meet the standards of Derzhspozhyvstandart: the norm for children, adults, animal feed, and biogas. It shows to which interval the results of the analysis belong. The analyser can also record the place where the analysis was performed, using a GPS tracker, and save a list of geolocations.

They also plan to add a Micotoxine risk-management prediction tool to the web service. The customer will receive a message about the potential contamination of the crops he or she works with and a list of actions and recommendations that should be done at the moment to diagnose infection at an early stage.

The device is currently going through pilot testing for maximum correction of all deficiencies. BIOsens already has potential customers in Europe, Africa, the USA, and Ukraine. Andrii notes that it is thanks to constant communications with them that the team manages to understand their needs better.

“We did a pilot test in Poland. We came to the agricultural company with our prototype; it was a blind test. They had samples and they already knew the concentration of mycotoxins in them. We performed the analysis on our device and compared the results. We had some differences in these results, after which we realised that we need to improve the device. Because it’s one story when you work in the laboratory with your own samples, but when there are other samples, that is, distinct varieties of corn, you can get an error in your result.”

In order for the BIOsens device to be sold and used, CE certification (European certification; FCC certification in the USA) and validation of analytical equipment are required. The CE certificate confirms that the device is not harmful to the user (due to electromagnetic waves, etc). The second procedure is more complicated and expensive and can take six months to a year. Within its framework, a process protocol is first developed, then internal validation is performed in production. The third step is validation in three independent laboratories. According to their findings, a certificate is issued confirming the technical characteristics of the device.

“Validation indicates that the device meets the stated characteristics of the manufacturer, that it measures with the accuracy stated by the manufacturer.”

BIOsens is currently in the process of internal validation of analytical equipment. The company plans to start external validation soon, as they have already received confirmation of its financing. To do this, it is necessary to address the reaction of the device to different varieties of cereals, which the developers encountered, in particular, during blind testing in Poland.

“Different varieties produce different noise to the analyser. If we take another variety, it has different characteristics of the matrix and it affects the results of the analysis. In 2020, the company planned to sell 20 devices, but the process of obtaining all necessary permits was stopped due to the coronavirus pandemic.”

Still, the developers of BIOsens did not waste time in these months:

“We worked on a filter that allowed us to use a cartridge with fine grinding and analyse the flour. We have also developed a new version of the optical unit, which we are currently testing. We have recently received positive results with pure toxin and plan to work with real samples.”

Customers

BIOsens identifies five categories of its potential customers. The first is farmers who grow cereals. The characteristics of this category differ from country to country because they all have different standards of control. And the higher the standards are, the more farmers are interested in timely product analysis. In case of a violation of these standards, they risk losing their reputation and the opportunity to sell grain because it will be infected. Moreover, it implies significant financial losses.

The second category is traders who grow cereals themselves or buy them from suppliers and export them to other countries. They require analysis for mycotoxins, as their permissible amount is usually specified in the contract.

“Traders are interested in this at the stage of a shipment formation. For example, they have 10 suppliers who deliver different batches of corn. If one of the batches is infected with mycotoxins, and it is placed with other batches, then there will be cross-contamination and the whole shipment will be infected.”

Cross-contamination

Contamination of raw materials, intermediate, or finished products with other types of raw materials or products during the production process.The third category is processors. These are the companies that buy raw materials and produce the final product, exercising control at the stage of purchasing grain.

The fourth category is livestock farmers. They need to know the level of mycotoxins in feed. If the feed is contaminated with toxic compounds, the animals have reduced immunity and live weight. This can even lead to death. In addition, if an animal eats food contaminated with mycotoxins, they can end up in meat, milk, eggs and thus enter the human body.

And the fifth category is consultants who provide advice to farmers.

Being a startup in Ukraine

Andrii Karpiuk is the founder of BIOsens and its executive director. While still studying at NULES (the National University of Life and Environmental Sciences of Ukraine), he became excited about the biosensors. The interest grew into a startup that united a whole team in a few years. And Andrii himself was included in the top 100 Eastern European technological innovators by the Financial Times.

Andrii had the idea of the BIOsens device as the follow-up of his candidate’s dissertation in 2016. The dissertation’s subject was the development of biosensors for rapid diagnostics of food safety indicators. Andrii began to apply this concept for various grants and hackathons.

Hackathon

An event in which teams solve a problem in a limited period of time.“In 2016, I came across a Facebook advertisement about the agro hackathon, filled out an application, and we participated. At that time I didn’t really understand what business, startup, and marketing meant or how to work with them. There was no team; there was only an idea.”

Today there are 6 people on the project team. Andrii’s partner, Oleksandr Hudz, is responsible for the IT side, including the mobile application and web service. Andrii met him during the hackathon.

“After the agro hackathon, we took part in the IoT (Internet of things) hub, where we worked on the first prototype and began to communicate with the first customers. As a result of this work, in six months we have attracted the first investments from Roman Kravchenko, who organised this IoT hub and at that time invested in various innovative projects. We spent this investment on marketing research.”

slideshow

Andrii Karpiuk says that he used to run electrical and vending companies meaning that he had some classical business experience, which starts and generates funds relatively quickly, according to a clear model. But this experience is barely comparable with creating a startup that has exponential growth and a large innovation component. And it was during this period that the BIOsens team learned to develop and scale innovative companies.

“I call the period from 2016 to 2018 the studying period. During this period we were not seriously engaged in business and promotion. We formed a team and developed its skills. After that, we started working on the product.”

For about a year, the project lived on Andrii’s personal savings. And later it got on acceleration to Switzerland. There, the team met and talked to a number of potential customers and found additional development points. In particular, at that time the team already had a prototype with an analysis sensor, but realised that the stage of sample preparation is of no less importance. This is the same stage that now distinguishes the almost ready device from other similar ones on the rapid diagnostics market. Therefore, after coming back, they started working on a prototype of sample preparation. At the same time, Igor Panas, an engineer who “has golden hands” and significantly improved the process of technical work on the device, joined the team.

“During this time, many people at one stage or another joined the development of the project. Someone came, performed his function and left. Someone came with some hopes that the project would develop faster, those hopes did not come true, and enthusiasm disappeared. Someone’s life priorities have changed.”

Since 2018, the team has applied for a number of grants, including financial support under the project ‘Climate Innovation Vouchers’, implemented by the NGO Greencubator with the assistance of the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development and the European Union.

“Innovation vouchers” is an opportunity for Ukrainian companies to acquire non-refundable funding for projects related to reducing greenhouse gas emissions. Thanks to the project, BIOsens has developed two engineering prototypes, which (with minor changes) are planned to be launched into production. They also created a mobile application and complete technical documentation for small-scale production.

Andrii Karpiuk decided to develop his business in Ukraine. His reasoning is devoid of illusions: he directly says that the national business environment carries many challenges for future entrepreneurs. And at the same time it offers as many opportunities and is rapidly developing:

“We are no longer afraid of the word ‘startup’ at the national level. In 2016, when I said this word at university, the scientific community would point fingers at me. And now at the same university, the administration encourages startups, new ideas, allocates funding for it.”

The founder of BIOsens believes that the right environment and funding helped to implement the project and bring it almost to the final stage.

“First, try to surround yourself with people who have already done what you want to do. When you do something for the first time, organisational issues often arise, and these people will help you find the answers. Secondly, the project requires financial support. If it is a hardware project, then you will need funds for the prototypes at the very beginning. If it is a software project, then a little later.”

Andrii Karpiuk hopes that over time, more and more innovative companies from Ukraine will work and pay taxes not only in the United States or Europe, but at home. But this requires working out the infrastructure and legal framework.

“For example, why can’t startups be exempt from taxation for the first two years? To officially register a team to the staff, rather than imposing taxes on them that they do not even earn. Such mechanisms are implemented in Poland, Estonia, and other countries.”

Startups in Ukraine are financed in two main ways: grants and investments. Both have their own specifics. And it is best when this direction is taken over by a person from outside the developers, because the process requires an educated approach and filling out applications.

“Regarding grants, you need to set up the right flow of information: register your project on the profile resources for the startups and then subscribe to the news on the subject.”

Andrii recalls how during the acceleration in Switzerland, the mentor advised him a simple thing: to enter “Ukraine startup financing” in a search engine and make an indicative list of such donors. In two years, in 2019, Andrii came across this very list in his notes. And it was there that he got to know about “Climate Innovation Vouchers”. The BIOsens team applied for this program and received funding. Once the information on available grants has been found and analysed, it is possible to proceed with the formation of grant applications.

“As our experience shows, application for grants is just a mathematical statistic. Sometimes it happens that the project is really very cool, but it is not clearly presented, or vice versa. And this must be understood at the beginning. Because it often happens that teams that have applied for several grants and received a refusal think: ‘We are a loser project. No one will support us’. Although in fact there may be a whole bunch of factors that influenced a certain decision.”

In the context of investment, Andrii advises to start with a list of 30 potential investment funds. You need to make a short summary of the project and send it for review. It should be understood that investment funds seek to get acquainted with the project, the team, the course of events, and the way people work to achieve the stated results. Therefore, it may take three to nine months before a startup receives funding.

“Not only money, but also their expertise and contacts are very important. My recommendation is to attract more smart investments. That is, that the investor who enters the project, in addition to funds, offers additional value to the company. These can be contacts with customers or manufacturers, personal experience of project development.”

Today, the BIOsens team is building a leading company in rapid diagnostics of the food safety indicators. Mycotoxins are the first challenge through which they intend to tell the market that they can produce a quality product. And in the future, they plan to expand the line to pesticides and pharmaceuticals. The main task is to enable people without special skills to analyse in the field and get the result in real time.

“Ukraine is the place where I was born, where I live and want to live in the future. And to live in a successful country, the economy must be developed. And it seems to me that startups and innovative projects that will develop, pay taxes, and create jobs, are the key to the success of the Ukrainian economy. BIOsens is my small contribution to the development of the dream country.”

supported by

Supported by Greencubator and Climate Innovation Vouchers projects, financed by European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, and European Union