Individual rule backed by fear and terror. Brutal reprisals against opponents, mainly for far-fetched reasons. Senseless wars against neighbouring states, often ending in defeats. A sincere belief in one’s own divine nature, and therefore the justice of one’s bloody actions. Poor but submissive subjects. This was the reign of the first Moscow Tsar Ivan IV (1530-1584). He is known in history as Ivan the Terrible.

Born during a lightning storm

“Fear the Tsar. Serve him faithfully and always pray to the Lord for him. Do not speak falsely in front of him, but humbly say the truth, as to God himself, and be obedient to him in everything,” says the collection of life rules Domostroy [home building – ed.] created by the royal confessor or Tsar’s cleric, and that every Muscovite had to live by.

Ivan the Terrible. Viktor Vasnetsov, 1897. Source: wikimedia.org

On August 25, 1530, at 7 am, the Earth was shaken by an unprecedented thunderstorm. At that moment, Ivan was born in the village of Kolomenskoye near Moscow. His father, Vasili III, was the Grand Prince of Moscow, who happily distributed vast amounts of money to monasteries and people. He ordered the dungeons to open and released many objectionable ones. When Ivan was 3 years old, he lost his father, when 7 — his mother. He was adopted by representatives of Boyar families (feudal nobility – ed.), who were replacing each other in the power struggle. The autocrat later sought to justify his cruelty by saying he was deprived as a child. “My brother and I were raised by strangers or beggars. How we lacked clothes and food! We were not allowed to do anything and were not treated like children. How often I was hungry while my father’s treasury, which I inherited, was treacherously stolen.”

The first person he took revenge on was Prince Andrii Shuyskyi. The Piskarev chronicler describes how 13-year-old Ivan “ordered him [the Prince] to be given to the dogs, and the dogs seized and killed him.” Two years later, “he ordered the execution of Ofonasii Buturlin. He also ordered that first Buturlin’s tongue be cut out in prison because he was guilty of saying an impolite word.” Subjects were not bothered by such reprisals. However, Sigismund von Herberstein, the envoy of the Roman emperor, was perplexed: “It is difficult to understand whether the people are so rude that they need a tyrant sovereign, or whether the people themselves become rude and cruel because of the tyranny of the sovereign.”

When Ivan was 16, he was solemnly crowned Ivan IV in the Moscow Assumption Cathedral. Subsequently, he expanded the title of ruler and became the Grand Sovereign, Tsar and Grand Prince of all Russia. He believed this was how to elevate himself to the level of an emperor. During the ceremony, signs of royal dignity were placed on him: the Cross of the Life-Giving Tree, a barma necklace and the Monomakh’s Cap, which is the work of the Golden Horde’s craftsmen. However, the Moscow clergy gave the headdress as a gift from the Byzantine Emperor Constantine IX to Prince Volodymyr when he ascended the Kyivan Rus’ throne.

The Tsar is not for everyone

The envoy of the Roman Emperor Daniel Prince described the Tsar without much reverence: “He is very tall. He has a strong, rather stocky body, big eyes that are constantly running and carefully watching everything. His beard is red, with a slight hint of black, rather long and thick. He shaves his head with a razor like most Muscovites do. He is very prone to anger, and when he is caught up in it, he gets mad like a horse and seems to fall into madness. He is ill-mannered. He leans his elbows on the table, does not use plates, takes food with his hands, and sometimes puts what he has not eaten back in the bowl. Before drinking or eating any of what is offered, he usually crosses himself and looks at the images of the Virgin Mary and St. Nicholas.”

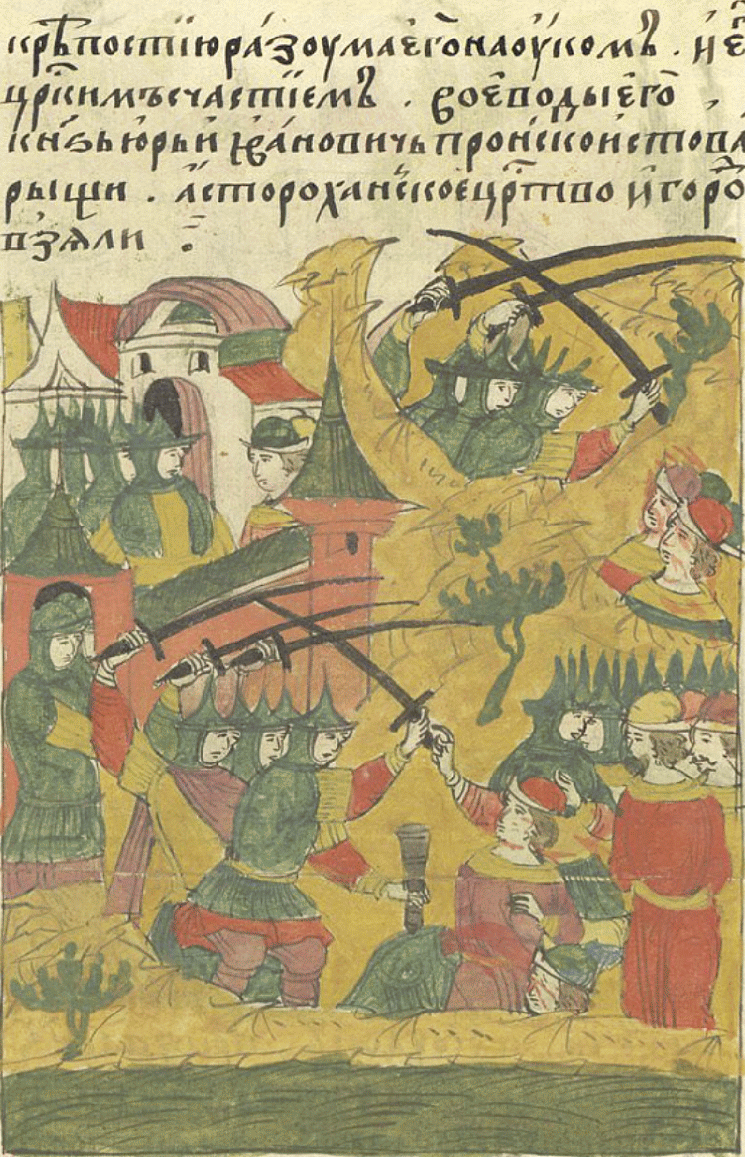

The Tsar craved new territories. The first targets were the Tatar States of the Volga region. The Muscovites easily conquered Kazan and Astrakhan, which opened the way for them to capture Siberia.

Capture of Astrakhan by Moscow troops. A miniature from the Lyceum chronicle vault, 16th century. Source: wikimedia.org

Hoping to reach the Baltic Sea, Ivan started the Livonian War, which lasted 25 years. Emperor Maximilian II sought to use the Muscovites’ powers in the war with the Ottoman Empire. To achieve this, he sent ambassadors who confirmed the right of Ivan IV to the royal title. But the Tsar decided not to fight with the Ottomans.

In 1572, King Sigismund II Augustus of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania died, leaving no male heir. Shortly before the monarch’s death, the Union of Lublin was signed, according to which Poland and Lithuania created a single state, the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, which was to be headed by an elected ruler. Ivan was also among the candidates. Lithuanian elites supported him, hoping to end the war with Moscow and strengthen their political and economic power in relations with the Poles.

However, the pamphleteer of that time wrote: “The Muscovite creates a solid foundation in order not to join Moscow to the kingdom, but to annex the kingdom to his tsardom, to make the capital in Kyiv so that he is crowned not by our bishops, but his metropolitan.” Ivan lost the King’s election and decided to focus on the war. He looked for arguments in a distorted and interpreted-in-his-own-favour story: “The Land of Livonia has been our fiefdom since time immemorial, since the time of Grand Prince Yaroslav, the son of Volodymyr the Great, who was baptised as George [Yurii in Ukrainian — ed.], who conquered the Land of Peipsi and put in it a city of Yuriiv [now Bila Tserkva — ed.] named after him, and in German called Derpt.”

Polish King Stephen Bathory did not recognize Ivan’s royal title and claims to his territories. Ivan replied: “I am the Tsar by the will of God, not by the great desire of mankind.” Bathory replied: “It is better to be born from a virtuous nobleman and noblewoman than from a dashing King and Queen,” and challenged his opponent to a jousting match. Ivan dodged. Then Báthory joined the Livonian war. The Poles defeated the Moscow Army. The English ambassador, Giles Fletcher, explained the reason for the defeat: “The Tsar hoped more for numbers than for the bravery of his soldiers or the good organisation of his forces.” Ivan had to agree to a humiliating peace. He ordered the ambassadors sent to negotiate “for Christian peace” and keep quiet if the King and the Sejm did not agree to call him Tsar.

Warriors with dog heads

Ivan was convinced of the divine origin of power and the naturalness of absolutism. In a letter to Prince Andrey Kurbsky, who fled to Lithuania because of the Tsar’s disgrace, he wrote: “He who opposes power opposes God’s will. If you are righteous and pious, why didn’t you want me, the wayward ruler, to suffer and earn the crown of eternal life? But for the sake of your body, you have lost your soul; for the sake of fleeting glory, you have despised the eternal, and you have taken revenge on your man and rebelled against God!” Kurbsky advised the Tsar to consider the experience of governing in other countries and find smart advisers. He replied indignantly: “Their tsars do not own their tsardoms, but as their subjects tell them, so they rule. The Moscow autocrats have always owned their own state.”

The Tsar actively implemented reforms: judicial, land, tax, and church. However, all of them had the same goal — to strengthen the personal power and well-being of the monarch. In 1565, the Oprichnina [state policy – ed.] was introduced in Muscovy. The twenty largest cities then had to transfer income to the sovereign’s treasury. This was followed by an army of oprichniks who had to renounce their relatives and friends in order to serve only the Tsar. They wore black clothing and strapped a broom and a dog’s head to the saddle — symbols of their main duties: gnawing on royal enemies as dogs and sweeping treason out of the country.

“You need a lot of dogs to catch a hare, and a lot of warriors to fight enemies,” Ivan explained.

Those who refused to enrol to become an oprichnik voluntarily were evicted.

People running away from the Tsar’'s mercenaries. Drawing by Apollinary Vasnetsov, 1911. Source: wikimedia.org

Princely and boyar fiefdoms were confiscated. The Moscow Tsardom was plunged into a maelstrom of severe persecution and bloody executions. The victims were not only likely political opponents of the autocrat but also their family members, servants and slaves. Ivan himself determined the execution. He ordered someone to cut off their arms and legs, and only after that — their heads. Others had their stomachs cut open. An individual could be sewn into a bearskin and harassed by dogs or tossed into a cauldron filled with oil, wine, or water, a fire lit, and the liquid gradually brought to a boil. In Novgorod, people were set on fire, tied to sledges and dragged along the frozen ground, leaving bloody streaks. Then they were thrown from the bridge into the Volkhov River. The wives of the executed had their hands and feet bound, their children were tied to them, and they were also thrown into the water. Those who surfaced were finished off by oprichniks with hooks and axes.

The Tsar ordered a nobleman named Ovtsyn [derived from the Russian word meaning “sheep” — ed.] to be hung on the same crossbar as a sheep. He ordered several monks to be tied to a barrel of gunpowder and blown up to let them fly to heaven like angels. The head of the embassy, Ivan Vyskovatyi, was tied to a pole, so the oprichniks approached the convict and each cut out a piece of meat from his body. Ivan Reutov “overdid it” and when he cut his piece, Vyskovatyi died. The Tsar decided that the oprichnik had done this intentionally to reduce the poor man’s torment. Reutov was supposed to be executed but fell ill with the plague and died.

Waiting for the uprising

“Although Almighty God punished the Russian land so hard and cruelly that no one can describe it, the current Grand Prince has achieved throughout the Russian land, throughout his entire state — one faith, one authority, one world! — wrote Heinrich von Staden in the Notes on Muscovy. — He’s the only one who rules! Everything he orders – everything is done. Everything he bans is really being banned. No one will contradict him, neither clergy nor laity. And only God Almighty knows how long this reign will last!”

Contemporaries explained the terror both by the Tsar’s mental illness and by his fear of losing power. But they could not explain why, until recently, rich and influential people haven’t dared to commit armed resistance to lawlessness. Giles Fletcher expressed: “Oppression and slavery are so obvious and so severe that it is very strange how the nobility and the people could submit to them. They had other means to avoid them or free themselves from them, even as tsars, now so firmly established on the throne, could be content with a former rule combined with such obvious injustice and oppression of their subjects, while they themselves profess the Christian faith.”

Commoners were also silent. “They live in exclusive slavery,” said Daniel Prince. – “They bear this burden easily because they know nothing about the structures of other tsardoms and states. They live in their own country like prisoners in cages and never dare to go out or send their children anywhere.”

The riot never started. The first Tsar of Moscow, Ivan IV, died himself, most likely from syphilis. During the 50 years and 105 days of his reign, approximately 40,000 subjects were executed and tortured. Already sick, the Tsar forgave some of his victims. Synodikons [decrees – ed.] were then sent to the monasteries to commemorate the victims, where almost 3,500 people were listed by name.

Ivan the Terrible and the shadows of his victims. Drawing by Mykhailo Klodt, beginning of the 20th century. Source: wikimedia.org