Ihor Reva and Solomiia Bratakh left behind city life in Lviv, moved to the village and founded a creamery. They restored an old Austro-Hungarian school building and set up a space for their company, ‘Harbuzovyi Rai’ (‘Pumpkin Paradise’ — tr.). Here, they make cheese and jam according to traditional and original recipes, welcome visitors, and organise tastings and workshops.

In recent years, there has been a rising demand in Ukraine for artisan food products, in particular dairy products like butter, yogurt and cheese. There are also a growing number of creameries whose founders promote traditional recipes or look for new flavours. These creameries often become centres for food tourism or ecotourism, places for culinary training and relaxation.

One of them is ‘Harbuzovyi Rai’ in the village of Mylchytsi in Halychyna, which produces about ten types of cheese with various flavours. In addition to direct sales and local fairs, their products are also stocked by some supermarket chains. For example, at ‘Silpo’, under the label ‘Lavka Tradytsii’ (‘Store of Traditions’ — tr.), which also supports this series of stories on local farmers and producers.

Converting a former school into a creamery

Ihor Reva is a dentist by training, while his wife Solomiia Bratakh is a pianist. The story of their move and the family creamery began when they were expecting their first baby. The couple realised that with two dogs, plus a baby on the way, their apartment would feel rather cramped. So in 2014 they left the city and bought a house in the village of Maliovanka, 30 kilometres from Lviv, in the foothills of the Carpathians.

— Our house is pretty much on the edge of the village. It used to be an isolated farmstead. Across the road we have a huge pasture, and beyond the pasture, a river and the huge Lubenskyi pond. Round about us, there are hardly any neighbours, and a whole lot of nature.

Ihor and Solomiia recall that in their first few months in the village, they tried their hand at various different activities, and began their journey into the food business by delivering goat’s milk to Lviv. Then they decided that was unprofitable, and started making dairy products.

— At first we tried everything. Everything was interesting, but we had no idea what to focus on. After a while you realise that if you do something, it has to feed you. We were constantly stopping one thing and starting to develop another.

For several years, Ihor and Solomiia made cheese at home on a small scale. But they received more and more orders, and decided to find another location for their creamery. They went round the nearby villages, not far from Lviv, and inspected the buildings. When they saw the Austro-Hungarian school in Mylchytsi, built in 1870, they realised it was just what they needed. However, it was in quite a poor state of repair:

— There was no roof, no ceiling, no windows — there was nothing at all. In the place where we now process milk, there were bushes and shrubs growing, and the basement was littered with rubbish. All the walls were covered with a rough layer of mould. The smell was truly unimaginable.

slideshow

Despite the neglect and the need for major repair work, the couple fell in love with this building on their very first visit:

— For quite a long time, we had been looking for a place to move our production line to. We were mostly offered old cowsheds or pigsties. Basically, Soviet buildings with zero history, with zero soul — just bits of brick. And then we came here and fell in love at first sight.

It took about a year to purchase the building. Another year was spent on the renovation work. In the summer of 2019, Ihor and Solomiia moved their production site to Mylchytsi.

Ihor says the building was used as a school until 1979, when a new school was built in the village and the old one fell into disrepair. In the 1990s, the old Austrian tiles were removed and the roof was covered with slate, which rotted a few years later. To restore the roof, the couple bought small batches of tiles from several villages, and cleaned them by hand. Then they battled with the builders, who wanted to get rid of all the wood with its old carvings. At every turn, Ihor and Solomiia defended their decision to preserve the building’s authenticity.

— It’s much more comfortable to work somewhere that’s invested not only with physical strength, but emotional strength too. You get something totally different out of it.

The creamery is named after one of their dogs, Pumpkin.

— When we moved here from Lviv, we already had two dogs. The older one’s name is Harbuzyk (‘Pumpkin’ — tr.). He was used to the city and going for walks on a lead. And then we get here, let him out of the car, and he realises: there’s a chicken, there’s a duck, there’s something else… He was just running up and down, he didn’t understand what was happening to him. And we realised that this was ‘Pumpkin Paradise’.

Making cheese

At the creamery, Ihor is in charge of production, and Solomiia looks after marketing and sales. Ihor’s interest in cheesemaking goes back to his university days:

— Every two or three weeks I would process 10-15 litres of milk for myself. I didn’t eat my first cheese, I gave it to the dog. The dog didn’t eat it either. I gave it to the pigeons, and the pigeons ate it.

Back then, in 2007, there was a lack of accessible information on cheesemaking, so Ihor read old literature and experimented a lot:

— To understand the workings of this craft, I had to get my hands on the technical literature. More precisely, how to do it at home, without Soviet systems or huge quantities of equipment that you don’t really need when you’re making cheese at home. I was reading old French books, pre-revolutionary Polish ones. Year after year, I would make a couple of dozen litres of milk. Like that.

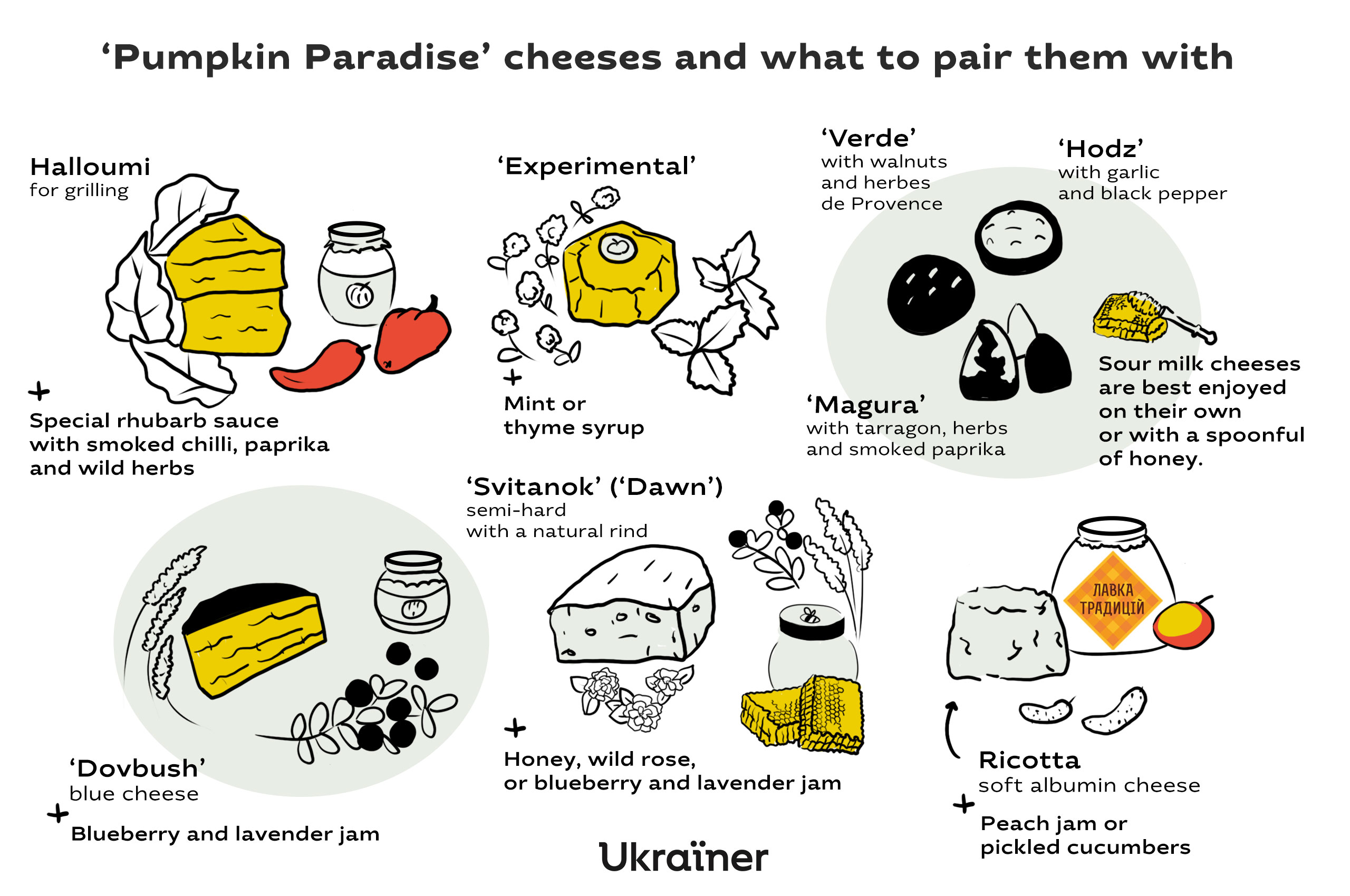

In total, the ‘Harbuzovyi Rai’ creamery produces about ten types of cheese, including: fresh, semi-hard, and blue cheeses; cheeses for grilling; pickled cheese; and spiced cheese.

— We always say that there’s no such thing as a unique cheese recipe. Because all cheese recipes are common knowledge, and in the Internet era it’s no secret. But a lot of factors come into play for every cheesemaker, starting with what the milk is like, and what the cow eats. A lot also depends on the cheesemaker’s hands. Of course, we took some classic recipes when we were learning. Then we adapted them however we wanted, to make the cheeses that we liked.

Ihor and Solomiia say that the real favourites are the medium-aged sour milk cheeses with different seasonings. ‘Hodz’ are balls of cheese with garlic and black pepper. ‘Magura’ are small pyramids with tarragon, herbs and smoked paprika. And ‘Verde’ are cheese balls with walnuts, basil and oregano. Halloumi is popular in summer because it works well on the grill.

In search of new tastes, acquaintances and experiences, the family even plan trips to creameries and dairy farms that interest them. They know some farmers in Croatia who supply them with truffles. According to Solomiia, the cheese with black truffles leaves nobody indifferent, thanks to its very particular taste.

The owners of ‘Harbuzovyi Rai’ come up with eclectic names for their cheeses. ‘Svitanok’ (‘Dawn’ — tr.) is so called because Ihor always has it for breakfast with his coffee. The blue cheese ‘Dovbush’ also has its own story:

— It came from the English word ‘bush’ and the Dovbush rocks (a group of natural and manmade rock structures near Ivano-Frankivsk — ed.), which are also green. And actually, blue cheeses ripen in caves. Somehow it worked in my imagination, hence the name ‘Dovbush’.

Three times a week, 500 litres of milk are processed at ‘Harbuzovyi Rai’, yielding between 50 to 75 kilograms of cheese, depending on the type. (Read more about the technology of making hard cheeses in the story of the ‘Mukko’ dairy farm and creamery). Ihor tells us the milk comes from a farm whose quality they trust.

— They take good care of their livestock, practice good hygiene, and control the quality of the feed. Because that’s important. You can send almost any kind of milk to a factory, but for small creameries, that doesn’t always work. We tried a lot of farms before finding milk that was more or less suitable for cheesemaking.

The cheeses are made without any chemical additives — just milk, bacterial cultures, enzymes, salt and spices.

— We don’t even use calcium chloride. It appears to be a safe food additive, but we don’t know how it was made or how it was transported and stored. I’m very careful about things like that. My children eat the cheese I make. The same goes for other people’s children. So it follows that we can’t allow ourselves to make a poor quality product, or use ingredients that might not be safe.

As well as making cheeses for order, the owners of ‘Harbuzovyi Rai’ work with fairs and supermarkets:

— We focus on direct sales. Either people come to us, or we deliver. In addition to direct sales, our products are at ‘Silpo’, in the ‘Lavka Tradytsii’ range, in small specialist stores, and that’s pretty much it.

Sauces, jams and syrups

In addition to dairy products, the family make jams, syrups and sauces with unusual combinations. On a small plot of land, Solomiia grows herbs and spices, including various varieties of mint. Lavender is in demand — it is used in syrups, and also as a flavouring for cheese. For each type of cheese they select the appropriate jam or sauce:

— We have home-made jams — two sweet and one hot and sour. First, blueberry and lavender. Second, ground wild rose petals. The third is more like a sauce, made from rhubarb. We highly recommend pairing it with our cheese for the grill — it tastes good with toasted cheese. As for sweet jams, they will bring out the taste of aged cheeses or blue cheeses.

The syrup and jam operations all started with mint. In the village, near the river, Solomiia came across a thicket of mint that none of the residents picked. Since there was nothing like it on the market, she decided to make syrup. At first she searched for old recipes, but later she and her husband developed their own.

The first batch was quite thick, like jam. As soon as they launched it in the online store, the orders came flooding in. The mint syrup has become a particular highlight at ‘Harbuzovyi Rai’.

The rose jam is something truly exclusive, made according to a traditional recipe. To make it, you need to grind the rose petals with sugar and lemon juice in a makitra (a traditional large clay bowl with a rough surface — ed.).

— This is our local variety. It has a very particular smell, and the petals have a very different texture from the roses in the south of Ukraine, where they make rose jam. The petals are soft as silk, and if you chew them, they’re both bitter and sweet. The flavour is tart: ground wild rose petals are all about tartness.

According to Ihor, ground wild rose has gone out of fashion recently, and it was difficult to buy it. So he and Solomiia planted and prepared their own wild roses, to preserve the regional tradition.

— I just have this thing: if there are no rose pampukhy (traditional Ukrainian buns or doughnuts — tr.) for the holiday, then there’s no holiday. It’s so tasty, and a lot of people have forgotten about it or didn’t know about it at all.

The couple share their pie recipe that works well with wild rose petals:

— Spread the rose petals onto crumbly shortcrust pastry, grate apples on top, cover it with beaten egg whites, and then grated pastry. This is my grandmother’s recipe, so I remember the taste from an early age. Take half of this pie and a huge litre mug of tea, and that’s your breakfast, lunch and dinner in one go, because you’ve got enough calories for the next two days.

Guests, workshops and dreams

On Sundays, on their terrace, the couple organise tastings and workshops that are open to everyone. Guests are invited to make a halloumi salad. Ihor and Solomiia also organise events where they teach people to make mozzarella, and cook four dishes over several hours. They also plan to set up a small petting zoo for children and other guests:

— Often, children come here and can’t tell a goose from a chicken. Something needs to be done about it.

The family are also planning to establish a larger rose plantation, move the tasting room to the second floor, and extend the grounds. Ihor dreams of having his own flock of sheep, to make blue sheep’s cheese:

— That’s my obsession. I really like sheep’s cheese because of its specific taste. And I really like blue cheeses. So sheep’s cheese with blue mould is a combination that makes me salivate.

Ihor and Solomiia never regretted moving out of town. Although their family business sometimes stops them from getting a good night’s sleep, the couple have managed to find symbiosis and derive pleasure from their shared project. Ihor shares his feelings about it:

— At the moment I can’t imagine my life without what we’re doing. I enjoy making cheese. I feel great when guests come to visit, and when they get excited about what they eat.

By endeavouring to seek out and recreate traditional recipes, Ihor and Solomiia show that Ukrainians can be proud of their culinary heritage.

— People are already beginning to understand that it’s cool. But we’re only just beginning to rid ourselves of the idea that “abroad is better”, and appreciate what’s ours. Our culture is so much older and more interesting than so many others. But for some reason, we value what’s elsewhere more than what we have here. We’re doing what we can to fix that.