In the second part of the explanatory series about the Holodomor, we decided to share the most famous and shocking fake facts about the 1932–1933 genocide in Ukraine. Most likely, you have heard many times that there was no Holodomor at all, or that there was a crop failure, or that there was a famine throughout the USSR, or that it was committed by Ukrainians themselves. In this article, we will refute the most common lies.

The Holodomor was a policy of the Soviet Union aimed at the destruction of the Ukrainian nation. It has been confirmed by hundreds of eyewitnesses, documents, and diary entries. At first glance, archival photos of the Holodomor victims, horrific stories about the realities of the “black boards” (or “boards of infamy”), bullying from activists, and the existing judicial system should have left no doubt about the crime committed by the Soviet regime. However, this historical trauma is still hard to recover from, as long as there are those who doubt its veracity. Therefore, below we will bust the so-called “myths” about the Holodomor of 1932–1933.

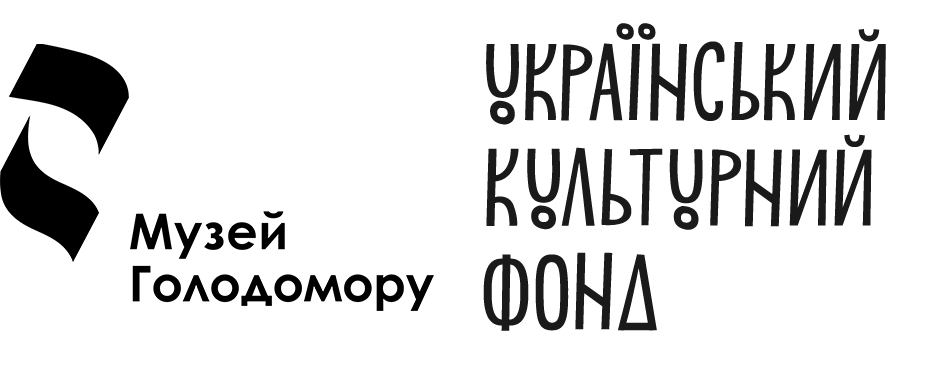

Death from starvation in the streets of Kharkiv, 1933. Photo taken by A. Wienerberger, an engineer. The photo documents were provided by A. Wienerberger’s great-granddaughter Samara Pearce.

There was no famine

“We do not raise issues of a far-fetched nature like the Holodomor, politicising

these common problems of the past,” the incumbent Russian President Vladimir Putin said back in 2008. Russia still maintains this position, fully confirming its image as the successor to the Soviet Union. These words reproduce one of the most common lies about the Holodomor, deliberately and scrupulously laid down by the Soviet authorities almost a century ago.

In general, the supporters of this myth often come up with claims that there was a famine, but it was not caused by the purposeful policy of the Soviet government; it was only by coincidence. Those circumstances were sabotage by the Ukrainian villagers, the need to keep the state afloat during the Great Depression, and adverse weather conditions. At the top of it is the statement that there was no Holodomor, because its scale and consequences are far-fetched.

Such a lie often makes people doubt how in the country that carried out modernisation, the famine was possible at all. Supposedly, the Soviet Union fed everyone. In the USSR as before in the Russian Empire, however, Ukraine, was only a raw material appendage. Its role was to provide ore and metals, and silently obey the system. Ukrainian villagers had no place in such a system.

Roman Podkur, a historian. Photo by Oleh Pereverzev.

“Food and all household items began to be issued by cards. The entire population was divided into 5 categories. The largest category was miners, metallurgists, and people of hard physical labour.” They were given 800 g of bread, 200 g of meat, a few fish, and a certain amount of butter per month. Several litres of oil and some porridge were provided. This was the minimum set of groceries for hard-working people. Other categories were “lower”. Category 5 included the dependents of the same workers. Farmers were not included in this system of centralised food supply which meant that they had to provide for themselves. Therefore, this is another lie, which states that the Soviet government fed everyone. Yes, it fed some people, but only those workers and employees who were in cities, as well as the Communist party elite,” the historian Roman Podkur says.

“If it (the Holodomor — tr.) happened, then why did everyone stay silent?”

“There were many different reasons: witnesses were afraid for their lives and suffered because of the traumas they had experienced; party leadership could not possibly recognise such actions; and the rest just did not have any information and were influenced with the Soviet propaganda.”

The 1930s experienced the peak of the Soviet repressions. The fictitious accusations of dissent, vicious counter-propaganda, cosmopolitanism, and bourgeois nationalism have led to millions of arrests and deportations to the Gulag, the system of Soviet forced-labour camps. Speaking openly in the Soviet Union about more than 7 million victims of a targeted policy of extermination of Ukrainians meant signing your own death sentence. Even among the party leadership, a very limited circle of people close to Stalin — Kosior, Kaganovich, Molotov, and Postyshev — knew about the real situation. Those who knew, hid the truth or blamed senior management, abdicating responsibility because they were already part of the system.

“In the Soviet state, it was possible for leadership to perform a lot of actions without documentary approval. Although when we talk about the Holodomor, there are documents, there is correspondence, there is a lot of evidence of the artificial nature of the famine. However, in any case, you could do a lot without talking about your real plans or talking about them through innuendos,” Vitalii Portnikov, a journalist.

slideshow

Another reason for the silence was the physical destruction of dozens of villages. There are less witnesses to these events since the entire families and the entire streets of villages from the “black boards” (“boards of infamy”), closed to entry and exit, have died out. The villages that did not fulfill the grain procurement plans were added to such a “black board”, which meant complete isolation from the outside world. They were surrounded by troops, and their inhabitants were completely deprived of food until they died.

“Wouldn’t other states start protesting against such inhuman events?”

“No, they would not. For other states, most information did not seep through the Iron Curtain of the totalitarian system.”

On 26 August 1933, the French politician Edouard Herriot arrived in Odesa aboard a steamship. Stalin ordered to organise a ‘tour’ for the guest and to draw his attention to the flourishing cities instead of bloated bodies in the villages. As a result, on 13 September, the newspaper ‘Pravda’ (‘Truth’) published an article entitled ‘What I have seen in Russia is beautiful’.”

Staged tours to villages that had died out from starvation and later were repopulated and presented as a model of prosperity (such as the village of Havrylivka in the Dnipropetrovsk region) — these were the typical methods of the USSR.

Photo by Oleh Pereverzev.

“It (the Soviet Union) could do it almost with impunity, simply explaining, ‘You know, there is famine in our territory; we are trying to help people, but not everything is in our power.’ The scale of the famine was hidden. Resolutions of the Soviet authorities that made this famine artificial were concealed. Moscow still claims that the famine was not artificial, based on all the decisions which were made during the Stalin rule and masked the true scale of the tragedy”, Vitalii Portnikov.

Evidence of the terrible famine in the USSR actually reached the foreign press. For example, after a trip to the USSR, the British journalist Gareth Jones held press conferences in Germany in March 1933. He stated: Ukraine as a part of the USSR is under the heaviest pressure, and hundreds of people are dying there without food. Several other journalists wrote about the events in Ukraine, such as Malcolm Maggeridge, as well as several publications in the United States. However, the problem with these people and publications was that they were not as trusted as their colleague Walter Duranty. The Pulitzer Prize winner, a close associate of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, and the only foreign journalist to interview Stalin in person, won. He claimed that the famine was only a fiction, that its scale was greatly exaggerated, and that temporary food shortages were a natural stage in the formation of the USSR. The public believed him.

In addition to the difficulties of entering the USSR, in 1933 foreigners staying in the Soviet Union were banned from visiting the territory of Ukrainian SSR and Kuban (the region of Russia inhabited mainly by Ukrainians). This decision of Stalin was provoked by the articles and statements of the Western journalists about the real situation in Ukraine. The press as the fourth estate, therefore, was deprived of almost all primary sources of information. With the outbreak of World War II, even single mentions were pushed out of the public sphere.

“Is there any evidence?”

“Yes. The evidence base contains thousands of documents (open and still hidden in the Moscow archives), testimonies of hundreds of thousands of eyewitnesses, researches, investigations, and many other materials.”

“Everyone says: prove the element of deliberate destruction of the population. These were grain procurement plans. It was the tool with which Stalin approached Ukraine and with which he began to punish it”, Roman Podkur states.

Today, the Holodomor is recognised as genocide by 17 states. In order to achieve this, it was necessary to prove the intentional actions against a specific group of people. Thousands of eyewitnesses told the truth, and their stories became the basis for such recognition. Human rights activist Raphael Lemkin also called the Holodomor a genocide. The testimonies were supplemented by archival documents that became available along with Ukraine’s independence. Today, the work continues, and researchers at the the Holodomor Museum keep interviewing eyewitnesses to the crime of genocide. More such stories can be viewed in the Ukraїner series about the Holodomor witnesses and on the Holodomor Museum website on the Testimonies page.

However, hundreds of pages of documents still remain locked in the Kremlin’s archives. Most likely, Russia will never provide access to them, as they only confirm the fact of genocide of the Ukrainian nation.

Preparation of grain for shipment to the filling station in the collective farm named after H. Petrovskyi. The village of Petrovo-Solonykha, the Mykolaiv Region, 1933. — The Pshenychnyi Central State Film, Photo and Sound Archive of Ukraine.

Poor crops caused the famine

This lie may be considered a variation of the previous one — they say there was no Holodomor, but there was famine due to crop failure. Moreover, there was no policy of Stalin and his supporters directed against the Ukrainian nation.

In fact, the Holodomor was not caused by a poor harvest. It was caused by the directed actions of the Soviet authorities — the destruction by famine — against the Ukrainian villagers. In 1932, no critical weather conditions were recorded that could lead to grain shortages and the deaths of more than 7 million people. That year, compared to 1931, less grain was actually harvested (12.8 million tons against 17.7 million tons in 1931). The reason for lower yields was the ill-considered policy of the grain procurement: in villages, there was not enough grain to sow fields, as it was increasingly exported out of the USSR, leaving nothing for sowing. Nevertheless, even that number would have been enough to avoid the famine if there had been no intentional policy of genocide.

“The regional Communist authorities , which were aware of the situation, never mentioned droughts or heavy rains. They only said that something happened in some areas, but it was very rare. They never mentioned the weather conditions. That is, if they did not mention the weather conditions and did not say that they became one of the main reasons for the mass starvation of the population, such conditions did not exist”, Roman Podkur.

In addition, eyewitnesses claim that, for example, there was no famine a few kilometres across the border in neighbouring villages and towns. For example, the border regions of Ukrainian Sivershchyna and Slobozhanshchyna suffered, but there were no crop problems nearby, in Russia or Belarus. In case of natural disasters, more than one state would suffer.

“As long as Ukraine retains its national unity, as long as its people continue to think of themselves as Ukrainians and to seek independence, so long Ukraine poses a serious threat to the very heart of Sovietism. It is no wonder that the Communist leaders attached the greatest importance to the Russification of this independent-minded member of their ‘Union of Republics,’ have determined to remake it to fit their pattern of one Russian nation. For the Ukrainian is not and has never been, a Russian. His culture, his temperament, his language, his religion — all are different… He has refused to be collectivised, accepting deportation, even death. And so it is peculiarly important that the Ukrainian be fitted into the procrustean pattern of the ideal Soviet man..” Raphael Lemkin, the founder of the concept of genocide, human rights activist. From his article: “Soviet Genocide in Ukraine”.

Collectivisation

Was a policy adopted by the Soviet government to force villagers to give up their individual farms and join large collective farms — “kolhosps”.

Savytska A., a member of the collective farm named after Comintern, the Yampil district, the Vinnytsia region, in the field while harvesting grain. The Vinnytsia region, 1939.

A more real trend of this period is that the famine of such a scale was exclusive in those regions where Ukrainians made up the majority of the population: Kuban, some areas of the North Caucasus, and the Lower and Middle Volga regions. The “black boards” policy was applied by the USSR nowhere but here, killing the entire villages. The most serious repressive resolutions concerned both Ukraine and Kuban. The organisers of the famine were the same people: in the North Caucasus, Mikoyan and Kaganovich personally controlled everything, and the latter later continued to organise the famine in Ukraine.

As of 1 January 1932, the Inviolable and Mobilization Funds of the USSR contained 2 billion tons of grain, and as of 1 January 1933, there were 3 billion tons of grain. These stocks were enough to feed 10 million people in 1932 and 15 million in 1933 (for comparison: more than 7 million people died in 2 years). In 1932–1933, the USSR actively exported grain. As of May 1933, 2,738,423 tons of grain harvested in 1932 were exported through seaports.

For fulfilling 97% of an annual plan for the supply of grain for export by Ukraine (i.e. for organising the Holodomor), Moscow rewarded the top leadership of the Ukrainian SSR with two cars. On 29 April 1933, P. Liubchenko, the Deputy Chairman of the Council of People’s Commissars of the Ukrainian SSR, signed a petition to award officials of the foreign trade department of Ukraine.

A woodcut “What is exported from Ukraine to Russia” from the album of graphics by Nil Khasevych.

The famine spread throughout the whole USSR

“The Russians… the Russian village of Bondarevo is seven kilometres away from us, from our village Hannusivka, so if women had blankets, towels or other things, they would bring them to the Russian village. Instead, they might give us a piece of bread… Russia did not starve. Right next door. Whoever was stronger, or whoever stood on their own feet, they took towels, they took everything to Russia. They exchanged those things, and thus they remained alive. And the Russians … they lived so close, and they didn’t live bad” (Povolotskyi I., born in 1927, Hannusivka village, the Novopskovsk district, the Luhansk region).

The Holodomor of 1932–1933 left many memories of eyewitnesses who lived on the borders of other Soviet republics. In the neighboring Russian village, there was at least some food and the opportunity to survive. People tried to escape not only to Ukrainian cities, but also to the east, to Russia proper.

In Stalin’s communication with those close to him, the organisers of the Holodomor, the topic of Ukraine was of particular importance. Numerous orders, minutes of party congresses and memoirs prove it.

The main instrument of population extermination was Moscow’s decision for unbearable grain procurement plans for Ukraine. From the harvest in 1932 of 12.8 million tons, 53% of grain was planned to be confiscated from Ukrainian villages, compared to 39% a year earlier, when the gross harvest was 17.7 million tons. The grain left was not enough for the normal physiological existence of the population. In fact, the seizure rate reached 70–75%, which put villagers at risk of death. To implement the plan, central authorities in Kyiv on 7 January 7 1933 demanded “to confiscate all available grain, including the so-called seed funds”. In fact, villages were left without any food or the opportunity to sow fields.

On 18 November 1932, the Central Committee of the Ukrainian Communist Party issued a resolution “On Measures to Strengthen Grain Procurement”. The practice of “boards of infamy” followed it. Specific decisions on the removal of villages from such “boards” were made by regional executive committees. In 1932–1933, 25% of districts, including 400 collective farms in the Kharkiv region, were in those boards.

The funeral of a village activist. Serhiivka, the Donetsk region, early 1930s.

Ukrainians did not resist

Another popular lie about the Holodomor is a variation on the theme of “blame the victim”: if Ukrainians did not resist, they themselves allowed such a situation to develop. The truth here is quite the opposite: it was because Ukrainians resisted that the Holodomor was committed.

“The Russian chauvinists, to whom Stalin essentially belonged, although he was a Bolshevik, were simply shocked by what was happening in the Ukrainian lands in 1917–1920. And even after Ukraine had been occupied by the USSR, the conversations about independence among the Communist Party elite continued. At the same time, farmer uprisings and resistance to collectivisation continued,” — Vitalii Portnikov says.

The absurd policy of the USSR, forced collectivisation, and assigning people to kolhosps (abbreviation for “collective farms” in Ukrainian — ed.) could not be perceived positively by private landowners, who were the majority of the villagers prior to the collectivisation. Up to 90% of Ukrainians lived in villages. So Stalin and his supporters turned to the total extermination of the Ukrainian population on national grounds.

“The rural population was actually “chained” to kolhosps, and it was impossible to quit them. It was a collective farm slavery, which stopped only somewhere in the mid-1960s. At that time, villagers actually started getting ID documents, which gave them the right to quit their jobs in kolhosps and leave”, Roman Podkur.

A group of activists of the Borova machine-tractor station in the Chernivtsi district, the Vinnytsia region. Borova village, 1936.

In 1930, one third of all village demonstrations against the Soviet rule among the republics of the USSR happened in Ukraine. More than a million people took part in them. In the same year, activists, grain procurement commissioners, and workers of the State Political Administration were attacked 2,779 times in Ukrainian villages. It was 20.12% of all of such cases across the USSR.

To stop such demonstrations, starting from the beginning of 1930 to 10 December, according to the government’s data, 70,407 farms in Ukraine were dekulakised. Of these, 31,993 families were deported (146,229 people): 19,658 families — to the Northern Krai (Land) of Russia, and 11,935 — to Siberia. However, the resistance of the population did not stop.

Dekulakisation

Was a form of repression against Ukrainian villagers, which included eviction and confiscation of all property, labelled as the so-called “class struggle against kulaks”, the well-off villagers.With the intensification of repression and the gradual seizure of not only grain but also food, people tried to set up stashes. There, in the pits, under the roofs, in the walls, in the stoves, people stored their food to save their families. Many of these stashes were found by patrols who would take everything down to a seed. People also tried to escape from starving villages to cities. Some went to neighboring villages where non-Ukrainians lived. In such villages, it was possible to find some food and thus survive and save one’s family.

For example, in January 1933, there were recorded occasions in the Kalynivka district when people openly laughed at kolhosp workers saying, “Why do you go to work at the kolhosp? Why? In any case, you won’t have anything from it”.

Running away from kolhosps and sabotage became another form of resistance. Thus, the official Karlson reported on 13 July 1932 that only in June 14,055 applications to quit kolhosps were received (in 4,754 kolhosps from 111 districts). Actively through protests or passively through sabotage, Ukrainians resisted the Soviet system with all their might, more than anywhere else in the USSR. And so, more than anywhere else in the USSR, they paid the price of more than 7 million lives.

A woodcut “What is exported from Russia to Ukraine” from the album of graphics by Nil Khasevych.

The Holodomor was organised by locals

The supporters of this false claim say that it is not Moscow to blame, but local, Ukrainian, officials who complied with the requirements of the grain procurement policy. However, they often omit one important detail — the positions of those who carried out these actions. Almost every one of them belonged to the Communist Party of Ukraine. That is, one way or another, each of the people involved, regardless of their nationality, was first and foremost a party member. And so, they were part of the Soviet occupation government. These people were not on the side of Ukrainians.

Nevertheless, even the committed communists tried to alleviate the situation of Ukrainians under such conditions. Some local activists and Komsomol members, unaware of the Kremlin’s real plans, could not understand how something could be done that would deliberately starve hundreds of people in villages and towns. For example, Dovzhynov, a secretary of the Liubar district party committee, and Basystyi, a head of the control commission, wrote to their senior leaders that “the obtained grain procurement plan can be fulfilled only if 58% of the gross harvest is delivered, which is against the party’s directives”. From the analytical report, dated 20 November 1932, it is clear that in Ukraine, discontent spread among the local authorities.

Komsomol

(an abbreviation for “Komunistychnyi Soiuz Molodi”, or the Communist Union of Youth), was an organisation the Soviet regime used to involve young people in the implementation of the state campaigns.“Our grandfather made stashes in the pits. In a wood, in his vegetable plot, in a yard. And in a field. He marked those places. He put some grass to look out from under the snow. We did not dig up beets planted in our vegetable plot. We dug them out already frozen. Authorities did not confiscate frozen beets. And we ate them. In summer, we would collect ears of grain, look for ground squirrels, catch corncrakes in the meadow, and eat pigeons. My grandfather had a pigeon-house, and we gradually ate birds from it. We lost our dog, and my grandfather said that wolves may have eaten it. They came — I saw them. Later, our mother told us that we had eaten that dog by ourselves. The Komsomol members would warn their relatives and tell their acquaintances to hide potatoes and food to survive. So they were shot later because of it”, Tsyba Vasyl, born in 1928, Raihorodok village, the Chernihiv region.

Local officials deliberately delayed the approval of grain procurement plans, later refused to comply with them, left the party, quit their jobs, and so on. In the Zhytomyr region, according to the official reports, the head of the village council of Bondarivka, a member of the Communist Party Ponomarchuk said at a meeting dedicated to grain procurement, “I can’t accept the plan. You can sue me and take away my party membership card.” The Soviet government acted uncompromisingly: such ultimatums were always carried out, severely punishing offenders for disobedience. Once the commissioner in the Melitopol district, A. Voltianskyi, deliberately shot himself in the forearm of his left hand in order not to take part in confiscation of grain. He was sentenced to 10 years in a concentration camp. And such cases were not uncommon.

At first, even the top party leadership of the Ukrainian SSR tried to convey Stalin that grain procurement plans were unrealistic. However, Stalin called Kosior, the then leader of the Ukrainian SSR, “a soft-hearted man”. After that, the repressios only intensified. The Communist party leadership was well aware of what was really going on in Ukraine at that time. The proof of this are numerous reports and notes on the real situation as well as evidence of strengthening of measures to destroy the Ukrainian villagers.

The transitional Red Flag of the Lozova machine-tractor station, awarded to the kolhosp named “New Life” (the Kharkiv region) for hard work during the sowing campaign. May 1932.

We have known everything about the Holodomor for a long time

In 1937, a census took place in the USSR. From the very beginning, it went a little differently than what was planned: it happened in one day. And after receiving the first results of the population census, Stalin ordered to keep everything secret. To be sure the information would not leak, the census organisers were repressed.

The USSR tried in every way to hide any mentions, documents, records, or publications that could confirm the death of millions of people in Ukraine. This was facilitated by the propaganda machine, which was able to silence the voices of dozens of journalists, even in the remote United States and United Kingdom. Under mysterious circumstances, birth and death records were disappearing, extinct villages were being inhabited, and people were dying (such as Gareth Jones, who died mysteriously during his trip to Inner Mongolia).

For a long time, the only evidence was the memories of those who survived and were able to escape to other countries. In the 1980s, James Mace collected the memories of hundreds of eyewitnesses about the Holodomor for the U.S. Special Commission. Piecing the accounts together, they were able to form a holistic picture and minimise the subjective factor. These memories proved that the Holodomor was genocide of the Ukrainian nation. However, many questions are still open to researchers, and many documents and archives are locked.

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, most of the archival documents relating to the repressions of the 1930s ended up in Moscow. There are countless documents, testimonies and, most likely, information about the actual number of those killed by the famine. All this information is necessary in order to fully understand the crime committed in 1932–1933 by the communist totalitarian regime with Stalin at its top.

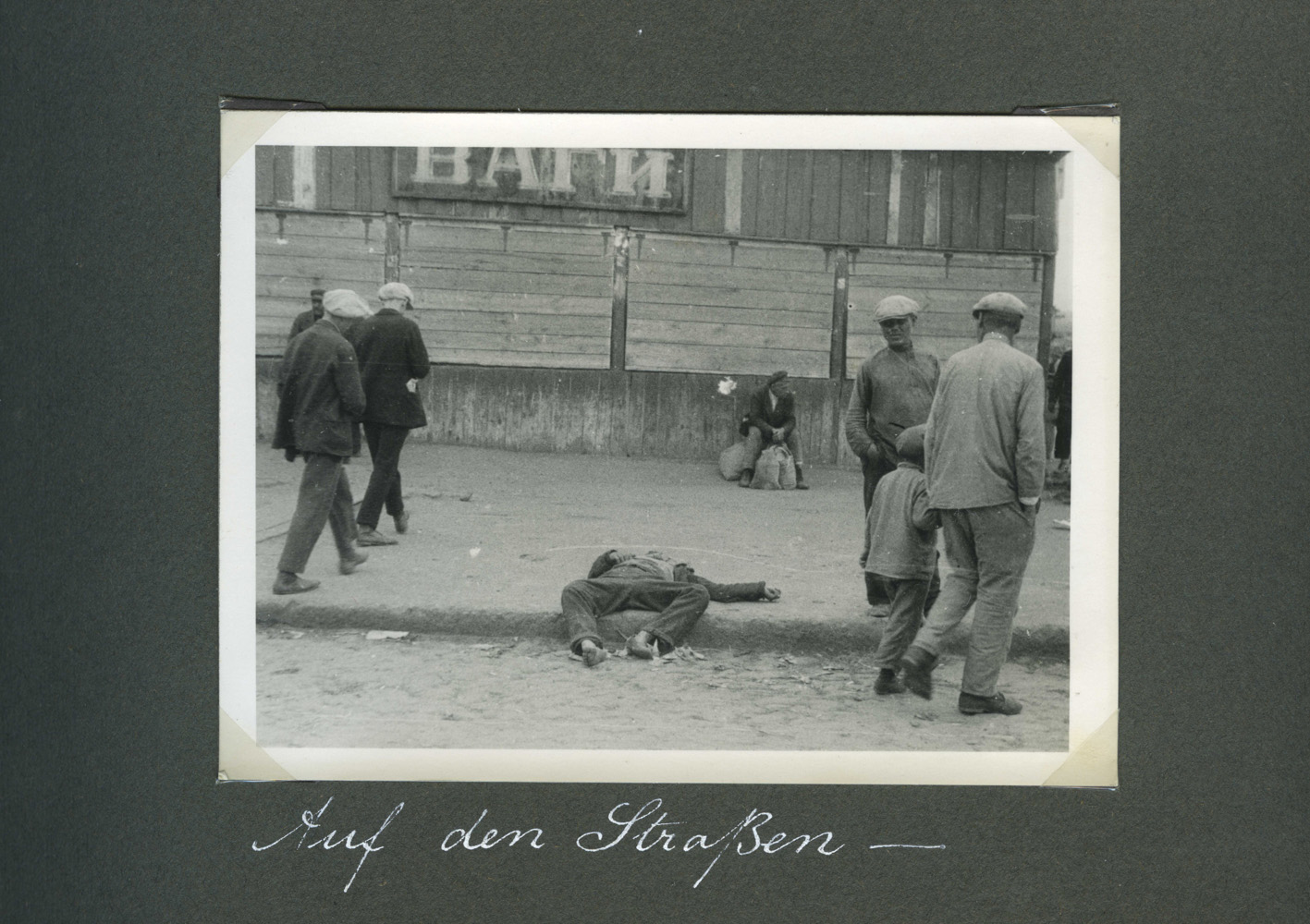

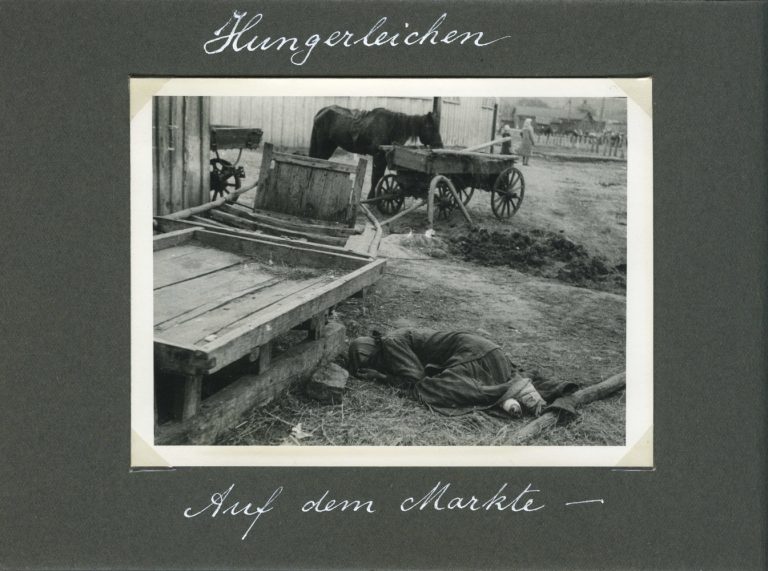

Victims of the famine. The Kharkiv region, 1933. Photo from the Collection of Cardinal Theodor Innitzer (Archive of the Diocese of Vienna). Photo taken by A. Wienerberger, an engineer. Photo documents were provided by A. Wienerberger’s great-granddaughter Samara Pearce.

The Holodomor was not genocide

Article II of the UN Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide:

Genocide means any of the following acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnic, racial or religious group, as such:

(a) Killing members of the group;

(b) Causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group;

(c) Deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part;

(d) Imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group;

(e) Forcibly transferring children of the group to another group.

The policy pursued by the Soviet Union in the territory of Ukraine was directed precisely against Ukrainians, and most of the Ukrainians were villagers. No other national group in the USSR has suffered such losses. Nowhere, except in the areas where Ukrainians lived compactly, were such methods used. The decisions of the top leadership of the USSR, medical registers, death registers, eyewitnesses’ accounts, and hundreds of other documents are proving it.

On 28 November 2006, the Supreme Council of Ukraine adopted the Law “On the Holodomor of 1932–1933 in Ukraine,” qualifying the Holodomor as genocide of the Ukrainian people. In May 2009, the Security Service of Ukraine opened proceedings “On the fact of committing genocide in 1932–1933”.

The investigation proved that the leadership of the Soviet Union intended to destroy part of the Ukrainian nation, which is paramount in proving the genocidal nature of the crime. The conclusion was as follows: the intention can be proved based on the relevant facts and circumstances.

By the resolution of the Kyiv Court of Appeal of 13 January 13 2010, it was proved that the Holodomor of 1932–1933 in Ukraine:

– Was planned to suppress the Ukrainian national liberation movement and prevent the creation of an independent Ukrainian state.

– Was committed through the forcible seizure of all foodstuffs from Ukrainian villagers and deprivation of their access to food. That is, the artificial creation of living conditions that led to the physical destruction of a specific part of the Ukrainian national group — the Ukrainian villagers.

– Was carried out as one of the stages of a special operation against the part of the Ukrainian national group as such. It was the Ukrainian nation, not national minorities, that was the subject of state-building self-determination, and only it could exercise the right to self-determination enshrined in the USSR Constitution of 1924 by leaving the USSR and forming an independent Ukrainian state.

– Was organised by the top leadership of the Soviet Communist regime, among which seven people, enlisted in the case, played a particularly important and active role in the commission of the crime.

The decision of the Court of Appeal named seven key people which were proved guilty of the Holodomor:

“The pre-trial investigation body established, with all completeness and comprehensiveness, the express intention of Stalin (born Dzhugashvili), Molotov (born Skryabin), Kaganovich, Postyshev, Kosior, Chubar, and Khatayevich to exterminate a part of the Ukrainian (and not any other) national group, and it is objectively proved that this intention concerned the Ukrainian national group as such.”

The Court paid particular attention to the retroactive effect of the law. Based on the provisions of Art. 7 of the European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms of 1950 and Art. 1 of the 1968 UN Convention on the Non-Applicability of Statutory Limitations to War Crimes and Crimes against Humanity, the court acknowledged that “there were no legal prohibitions on the application of Part 1 of Art. 442 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine in reverse time” to the actions of persons who had committed the crime of genocide of 1932-1933 in Ukraine. Thus, in the legal context at the state level in Ukraine, the Holodomor is recognised as a crime against humanity and genocide of the Ukrainian people.

A victim of the Holodomor. Kharkiv, 1933. Photos from the Collection of Cardinal Theodor Innitzer (Archive of the Diocese of Vienna). Photo taken by A. Wienerberger, an engineer. Photo documents were provided by A. Wienerberger’s great-granddaughter Samara Pearce.

Along with Ukraine, 17 other states recognised the Holodomor as genocide: Estonia, Australia, Canada, Hungary, Vatican City, Lithuania, Georgia, Poland, Peru, Paraguay, Ecuador, Colombia, Mexico, Latvia, Portugal, and the United States.

“This is not simply a case of mass murder. It is a case of genocide, of destruction, not of individuals only, but of a culture and a nation. If it were possible to do this even without suffering we would still be driven to condemn it, for the family of minds, the unity of ideas, of language and of customs that form what we call a nation that constitutes one of the most important of all our means of civilisation and progress”, Raphael Lemkin, “Soviet Genocide in Ukraine”

supported by

The material was published in cooperation with the National Museum of the Holodomor-Genocide with the support of the Ukrainian Cultural Foundation.