Crimean Tatars (Crimean Tatar: qırımtatarlar) are indigenous people of Turkic origin formed on the Crimean Peninsula and in the steppe areas of Ukraine.

They have survived three occupations. First in 1783 when the Crimean Khanate was annexed by the Russian Empire. This resulted in many Crimean Tatars fleeing to the territory of the Ottoman Empire during the late 18th to early 19th century.

The second deportation of Crimean Tatars took place in 1944, organised by the Soviet government. Then, on 18 May and during several following days, over 191 thousand people were deported to Central Asia and some north-eastern regions of Russia. According to different estimations, the deportation took lives of from one-third to half of the Crimean Tatar population of that time.

Having returned home after the deportation as Ukraine had become independent, Crimean Tatars were forced to leave their land again due to the annexation of Crimea by the Russian Federation in 2014.

In spite of not having known a peaceful life, Crimean Tatars did manage to preserve their culture and traditions. Most of Crimean Tatars have active civic position, as they stand up for the Ukrainian Crimea. It is them who now voice the statement “Crimea is Ukraine” most.

Oraza bayram

Crimean Tatars follow Islam, and thus they celebrate most of the Muslim holidays, including Oraza bayram (Crimean Tatar name for Eid al-Fitr — tr.). This is the holiday which concludes the 30-day fast from sunrise till sunset during the holy month of Ramadan (Crimean Tatar: Ramazan). Fasting during Ramazan is not only a physical challenge but also a psychological and emotional one, when you must keep your thoughts and mind in purity.

The holiest is the 27th night of Ramazan called ‘kadir gecesi’. It takes several days to prepare for it: people clean their houses, tidy up cemeteries, prepare clean clothes for themselves and so on. The day before this holiday, they celebrate ‘arfe gecesi’: in the evening, they usually prepare a festive meal including ‘qatlama’ (a dish similar to pancakes — ed.), chebureky (deep-fried turnovers filled with minced meat and onions — tr.), sweets.

slideshow

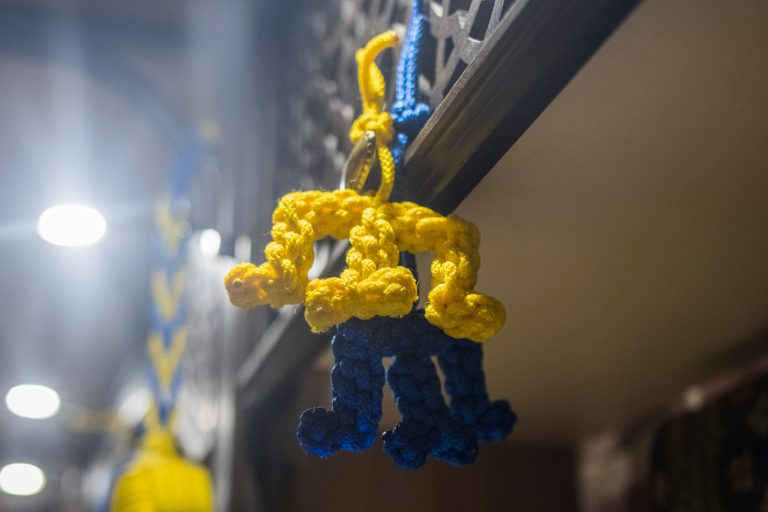

In Crimea, Oraza bayram has always been a family holiday. In Kyiv, however, in 2019 Crimean Tatars took part in the East Fest festival for the first time, which included celebrating Oraza bayram, as the festivities took place on the territory of the exhibition centre VDNG.

The festivities in mainland Ukraine are typically organised in mosques. The celebration starts with a holiday namaz, a prayer done five times a day.

Ramazan is a month of fasting and generosity. During the whole month almost every day, ‘iftar’, an evening meal to break the fast, is organised in the prayer hall of the Kyiv centre of Religious Administration of Muslims of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea (RAMARC). They prepare a free meal for those who fasted during the day.

Aider Rustamov. Spiritual life

Aider Rustamov, the Mufti of the RAMARC in mainland Ukraine says that before the Russian occupation in Crimea they used to organise only small celebrations because the local government of that time was reluctant to assist Muslims to hold large-scale events. According to Aider, there was also a problem in communication and misunderstanding among the Crimean Muslims. Overall, as the Mufti says, even before occupation, in Crimea there had been no understanding of how to consolidate the Muslim community.

Aider and his father were born in deportation. Aider was born in Central Asia, while his grandparents — in Crimea:

— I guess, I was in the third year of primary school when we moved from Central Asia to Crimea. We found grandma’s house. I remember it vividly. Just imagine this: grandma found her home where she was born and raised. She cried.

Aider finished school in Crimea, but he went to a university in Jordan to study the Arabic language and literature. Having come back to Crimea after graduation, he translated Islamic religious literature from Arabic to Crimean Tatar. Before he became the Mufti, Aider was taking care of his own business on the peninsula.

After the occupation of Crimea, Aider Rustamov’s family moved to mainland Ukraine, and they’re doing everything possible to come back home.

In 2016 the Crimean Tatars who left Crimea organised a general assembly in mainland Ukraine where they formed 14 mainland communities and officially elected Aider Rustamov as the Mufti of Crimea.

According to Aider, the Mufti is a representative of religious power, but he mustn’t aspire to take that high a position. By Islamic law, if a person strives for power, the person doesn’t deserve the power.

Each community delegates three people to the Mufti elections: the head of the community, the imam (religious guide — ed.) and another eligible person. Then they choose one of the three.

The top priority for the Mufti is to maintain the identity of the Crimean Tatars in the world. He is also ready to do everything possible for Crimea to return to Ukraine:

— We must value what we have now in Ukraine. I believe Ukraine is my motherland. Crimea is Ukraine. We feel free here. People who flee to mainland Ukraine say it even feels different to breathe here.

Now the Crimean Tatar religious organisations cannot exist freely in Crimea. The Mufti says that the religious centres remaining on the peninsula are forced to cooperate with the occupants. For this reason, the Crimean Tatars decided to create a new religious organisation RAMARC which is based in Kyiv in Nyvky district.

For over a year there has been a prayer house. Now both men and women can pray here: there are separate prayer halls in the building and big tents outside (men and women who follow Islam pray separately after the age of seven — ed). At first, few people came here, but now they have to put mats in the corridors so that everybody has space to pray.

RAMARC is a religious platform, a religious institute of Crimean Tatars which closely cooperates with the Crimean Tatar parliament, the Mejlis. They cover several domains: education, charity, social activity, hajj, and umrah. Hajj is a big pilgrimage. Umrah is a small pilgrimage. Every Muslim must go on pilgrimage to holy places once a year:

— We’re now trying to organise hajj so that all our compatriots can go on hajj affordably with Ukrainian passports. Many of our compatriots have money, but they don’t want to go with Russian passports.

RAMARC organises a Sunday school for children to bring up the national spirit in them and to make them intellectually richer.

The Mufti says they have the intention to open their school. Besides Sunday school, they also want to open a kindergarten with Quran readings, learning English and Arabic.

In 1988 when Aider moved to Crimea, his family settled in the village Oleksiyivka of Pervomaiskyi region (before 1945 called Eski Ali Keç in Crimean Tatar). There the school studies were all in Russian, but they had an optional class of Ukrainian which Aider attended:

— I even wrote dictations better than the local Ukrainians and Russians. But we had no speaking practice.

Tamila Ravil Qizi Tasheva. Public activism

Tamila Ravil Qizi Tasheva is one of those helping the displaced from Crimea and contributing to the development of Crimean Tatar culture in Ukraine. Despite having moved to Kyiv as early as 2007 for an internship at the Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine, Tamila still cannot go to the peninsula:

— Of course, this upsets me, it’s hard because my parents live there, and my close ones still live in Crimea.

After her work at the Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine, Tamila found a variety of activities: culture management, organisation of different kinds of festivals and other art events:

— The only thing I never lost interest in is developing the Crimean Tatar culture, doing so in certain collaboration with the Ukrainian culture.

Together with Oleg Skrypka (a Ukrainian musician — tr.) for a few years in a row, they organised ethnic stages for Crimean Tatars as part of the Kraina Mriy festival.

— This must be true that those doing most for popularisation of the Crimean Tatar culture have always been the people who have left Crimea for quite a while.

Public activist and media consultant Alim Aliev develops the Crimean Tatar culture in Lviv while Tamila does in Kyiv. For example, in Lviv, they organised festivals of the Crimean Tatar culture where they invited Ukrainian and Crimean Tatar musicians. Every year they held various events for musicians and artists from Crimea. A few other festivals were organised in Kyiv, but they hadn’t been so well-known before 2014:

— The year 2014 was a turning point. Big grief came to us: the war, territory annexation. But along with that for Crimean Tatars, for their recognition in the Ukrainian society came understanding that Crimean Tatars are an indigenous people of Ukraine, an ethnic community that needs support.

CrimeaSOS

Tamila Tasheva, Alim Aliev, and Sevgil Musaieva were activists of the Revolution of Dignity in 2013-2014, and they kept the Crimean Tatar flag constantly visible. On 27 February 2014, they found out that the administration buildings in Crimea, in Simferopol had been seized by unknown people in military uniforms. Back then it was already clear that it must have been done by Russia:

— At that moment we were still hoping it would somehow get resolved. But in the afternoon, it was at around 1 or 2 o’clock we sat down together in the office and created a Facebook page. I clearly remember this call to our audience: “We’re CrimeaSOS, we’ll be telling you the news directly from Crimea”.

The organisation was informing and explaining to Ukrainians and foreign journalists about the events in Crimea through their contacts with Crimean bloggers, journalists, public activists. Tamila says that after a week they had over 15 thousand followers on their page and numerous mentions of their community. At first, the team aimed to merely provide the information support of all events, but it didn’t take long for them to realise that besides information there was also a need for direct help, like it had been at Maidan.

In March 2014, the activists of CrimeaSOS created an email box that received offers from Ukrainians to host somebody from Crimea in their home. The hotline received calls from those willing to leave as they were afraid to stay in Crimea and couldn’t understand what was going on as people in military uniforms were entering cities and villages.

Starting in 2017, besides helping the displaced, CrimeaSOS began active work with people persecuted in Crimea. They started working with lawyers, activists, and journalists directly on the peninsula.

Moreover, the CrimeaSOS team is working with the communities of displaced people, specifically assisting in their development. They train the newly-formed organisations to operate in Ukraine, show them ways to enhance their activity, teach them to find resources, to communicate through mass media, etc.

During that period they managed to help tens of thousands of people: found accommodation, offered legal, social, and psychological help. For example, social support included a basic needs pack containing hygiene products, food and so on. They also assisted in opening and developing small business in the first years so that they find it easier to integrate on the mainland.

In 2014-2015 the state government had not figured out yet how they were supposed to react to the challenges in the society. At that time there was no legislation to regulate the status of internally displaced persons neither from Crimea nor from Donbas:

— Not only were we helping directly, but also we were writing laws. The first law concerning internally displaced persons was being written in our office.

Tamila’s parents refused to leave Crimea. Her sister and nephew also stayed there:

— Two years ago my grandma died, and I wasn’t able to see her. And I hadn’t seen her during those three years, since 2014. Of course, it’s all very hard psychologically, as you understand that since the Russian Federation considers the territory of Crimea their own, I can’t go there. My life would be in danger there.

Community

The world’s and Ukraine’s attitude towards the Crimean Tatar community has notably changed since 2014. Before that time the Crimean Tatars in Crimea had been seen as a group that can potentially separate in favour of, say, Turkey. According to Tamila Ravil Qizi Tasheva, Ukraine had been gradually losing Crimea ever since the declaration of independence because the Kyiv authorities paid no attention to Crimea, namely, there was no concise information policy and public work with the population of Crimea. Russia, in its turn, had invested colossal resources into public associations in Crimea and into propaganda via mass media.

slideshow

— When I moved to Kyiv from Crimea in 2007, nobody was biased against me, as they knew hardly anything about Crimean Tatars. They did know that once a year Crimean Tatars come out in the streets on 18 May because it’s some kind of a terrible date of theirs. They didn’t even realise it was about deportation, a crime against humanity, a genocide.

By 2014 hardly anybody had known about Crimean Tatars and their tragedy. Occasionally, some activists had to explain this through culture. Mostly, they explained it with their own example: who Crimean Tatars are, who they are, that they are a European nation hoping for welfare in Ukraine, for it to become a rich and strong state. Because only in Ukraine as a European state can the rights of indigenous peoples’ ethnic communities be respected:

— I remember the year 2014 when we announced we needed help to find accommodation for people leaving the peninsula. Then thousands of people started texting us that they can offer accommodation. For example, Oleg Skrypka called me in March 2014 and said: “Listen, Tamila, I have a house not far from Kyiv, it’s empty. If you need to host somebody of your family, or somebody you know, please, use this house”. And that was very important.

In autumn 2018 the Ilko Kucheriv Democratic Initiatives Foundation held a sociological survey. Among other questions, Ukrainians were also asked if they supported the idea of Crimean Tatars being granted the right of self-determination within the borders of the Ukrainian state. In other words, the question was about the national territorial autonomy as part of the Ukrainian state. Over 50% of Ukrainians responded in favour of granting this right to Crimean Tatars. This is a good ratio as it shows that Crimean Tatars aren’t treated with hostility, aren’t seen as separatist groups.

The Crimean Tatars see themselves and position themselves as indigenous people of Crimea and Ukraine:

—Sure thing, Crimea is and has always been my home, but Crimea is an integral part of the Ukrainian state, Crimea is Ukraine.

Kyiv has become Tamila’s second home as she has lived here for many years and most of her friends do. But she can never feel completely happy as long as she isn’t free to travel to Crimea because that’s where her roots are:

— I want to come to my home, drink my mom’s coffee, I want her to stroke my hair, cook some of her tasty dishes for me in our house.

Every time when Tamila came to the Crimea, she visited Bakhchysarai:

— I clearly remember the mountainous plateau over Bakhchysarai. That is my place of power. Every time I went there, I would sit down, meditate, look over at Bakhchysarai with its narrow medieval streets. That is the view I want to see not only in my dreams and imagination, but I want my dreams to be real, because for me they are so sensual and dimensional.

Crimean Tatars don’t have the idea of a ‘correct’ or ‘wrong’ Crimean Tatar. Some people choose the way of uniting with Allah and leading a righteous life according to the norms of Islam while others opt for a more secular life. There are Crimean Tatar women wearing hijab (a veil worn by some Muslim women — tr.) and doing namaz 5 times a day while living an active secular life:

— Some wear a jacket and jeans, others wear a veil and a long dress, and this doesn’t keep us from feeling we’re Crimean Tatars. We have something that unites us: religion, language, love of our motherland, the history of movement.

— I hugged people who wear hijab and people don’t wear hijab. It makes no difference whether you are orthodox or not. We must celebrate and value this diversity we have, because I think this is what makes the value of Ukraine: our diversity. And this is very important, not every country can boast about that.

Each national community can contribute to the diversity of this unique country.

Eskender Budzhurov. Business

On the eve of Oraza bayram there is a custom to fry something. Typically, they fry chebureky. And on the very holiday, they tend to experiment with various dishes.

In November 2019 it’s five years since Crimean Tatars Eskender Budzhurov and his son Asan opened a cheburek restaurant Sofra in Podil (a historic neighborhood in Kyiv — tr.). The word ‘sofra’ in Crimean Tatar means ‘a table laid with treats’. Now it’s the most popular cheburek restaurant in Kyiv. The Crimean atmosphere is created by the chebureky and also by the Ukrainian language which they speak here. They consider themselves a part of Ukraine.

As he was studying in Kyiv, in 2014, Asan called his father and said he was longing for a Crimean cheburek and that the Kyiv chebureky have nothing in common with the real ones.

At that time, Eskender’s family in Crimea understood they wanted to work and create something not related to war. So, all the family decided to move to Kyiv and open a cheburek restaurant. Asan had found a place for the kiosk. Being an architect by education, he developed the design of the interior and furniture himself. By the time Eskender moved to Kyiv, the place had been ready.

Two months passed between the idea and its implementation. However, the Budzhurovs had no production experience, they only knew how to fry chebureky and bake yantiq (a kind of cheburek fried with no oil — tr.) at home:

— Nobody helped us, we made this happen, the two of us.

Thanks to social media and the times when the founders of Sofra were invited on TV, their little restaurant became popular:

— Cheburek is our national dish. We cook it a lot and in different ways. A woman would always have a piece of dough and some minced meat at home. In a blink of an eye, she could pour some oil, heat the pan, and fry some chebureky. This is how it used to be done at our home.

At first, Eskender cooked chebureky in his restaurant himself. He’s remembering how he was trying to reproduce the domestic ways:

— When I only started, I didn’t manage to make them beautiful, and later they were getting nicer and nicer, and then I could make them all the same: neat and beautiful.

Now the Budzhurovs already have a few restaurants in Kyiv where they cook national Crimean Tatar dishes, some of which were borrowed from Central Asian cuisine:

— We borrowed some of the dishes from Uzbek cuisine as we had lived there for a long time. We also cook Uigur (a Turkic ethnic group in Central and Eastern Asia — tr.) dishes because we know much about them.

slideshow

Eskender was born in Central Asia, not far from Tashkent. There he finished school and graduated from university. He came back to Crimea in 1989. Because his passport said ‘Crimean Tatar’ in the nationality field, it was hard for Eskender to find a job. First, he was shipping citrus fruits from Turkey to Crimea, then delivering flowers and working in a consulting company. That had been his life until 2014:

— But everything changed when they imposed that referendum on us. It was fake. There weren’t so many people as Russian propaganda reported. Maybe 10 to 15 percent of the population took part in that referendum.

Now the Budzhurovs say they would like to visit Crimea, but here something has already grown to attach them, everything works, the feeling of responsibility has appeared. They can’t leave their staff behind, as during those few years they’ve built a great team and found many grateful customers.

Jamala. Music with Ukrainian DNA

Every year, Susana Camaladinova, more commonly known as singer Jamala, celebrates the Independence Day of Ukraine, Kurban bayram, and Oraza bayram. If she can, she fasts during Ramadan and keeps the tradition of family celebrations going:

— We always try to have a family get-together and eat some traditional dishes: pilav (a rice dish — tr.), chorba (a kind of soup — tr.), manty (a kind of dumpling — tr.). These are traditions that I like very much, when we come together, give presents to each other. It’s something like the New Year’s Eve. Such a lovely day.

Earlier, as Jamala says, the Crimean Tatars would celebrate in a restaurant where they met after Ramadan or for iftar. It’s a tradition where they treat everyone, even the non-Muslims. Jamala met her husband-to-be at one of such parties:

— They are vitally important. And I’m the proof. When the youth come together, meet, get to know each other, discuss the pressing problems in their mother tongue — this really unites and inspires them. I believe it’s very important that each nationality consider themselves Ukrainians, but also preserve their roots.

During the holidays, secular and orthodox Crimeans celebrate the same. For example, at weddings, which are important. Because it was at the wedding when they exchanged culture in times when there was no TV or Internet. It was when they wore the best clothes, jewellery, and tried to connect the families.

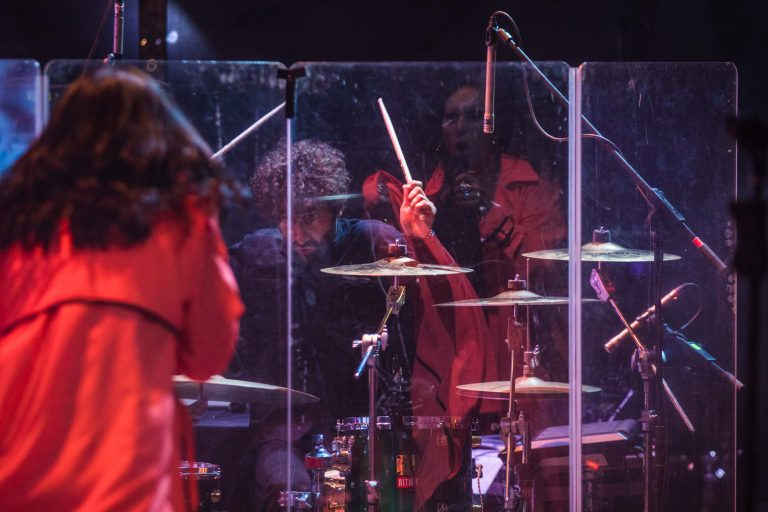

slideshow

Jamala says it was at the weddings that they created music, united into bands, got to know each other. There was no need in meeting at a cafe, wedding was the place to go. For this reason, when it’s wedding time, everyone is invited:

— When we were planning our wedding with Bekir, we didn’t know where to do it, as there wasn’t such a big venue in Kyiv to invite all our relatives. We combined the traditions of Crimean Tatar and Ukrainian weddings. We had millet and poetry in Ukrainian. I wore the common white dress, and a Crimean Tatar dress. It is at the wedding when religion and secular life are united as there are both a rite taking place in mosque, and a simple moment when the guests just get together and enjoy the food.

— Crimea is Ukraine. And I believe for me it’s motherland. It’s a place where I gave birth to my first son, where I make my music inspired by the Ukrainian melodies, by the Crimean Tatar melodies, by the American sound, which I listened to as a child. All this is mixed, and it’s completely Ukrainian music made by Ukrainian musicians, it has Ukrainian DNA.

When Jamala represented Ukraine at the Eurovision Song Contest, it was important for her not only to represent Ukraine, but her Crimean Tatar background was also indispensable.

— Yes, there’s this story in me about 1944 which I told to the world and what it means to me, how it’s connected to Ukraine. It was never the case that I separated myself from this.

The American approach in which all nationalities, Americans, Mexicans and others can unite being the citizens of one state is close for Jamala:

— When we know where we come from it’s easier for us to walk the world. Many problems come across every day. But when you know for good that you are a Crimean Tatar woman from Ukraine and you stand that ground, then you become more complete and collected.

— There were concerns voiced like “Why, we have nobody more Ukrainian than Jamala?” This was going on when I sang my song 1944 for Vidbir (contest to define the representative of Ukraine for Eurovision — tr.) and won. This was going on then, and it scares me a lot. And it’s offensive because I adore my country and I always come back here with love. I wouldn’t want to live anywhere but here. And I want us to move forward. That’s how my parents brought me up. I’m a patriot of my country.

Jamala also stresses how important it is today to support the Crimean Tatars who stayed in the occupied Crimea for any reasons. We must tell them they’re a part of the community. Jamala believes that the current situation is temporary and one day she’ll be able to come back home:

— I have one dream that concerns all of us. For Crimea to be a part of Ukraine so that I can come home with my son.