Houses with orchards and sizeable yards, where one can hear both Czech and Ukrainian languages. Concrete footpaths, and a well looked after church. These are the typical sights of the Bohemka village in Prychornomoria. The village was founded in the early 20th century by Czech Evangelicals who were fleeing oppression of the Catholic church. Several families settled in the steppes of what was then the Kherson province of the Russian Empire, where they built a village and formed a linguistic and cultural centre with their own school, church, and a cultural hall. Today about half of the village population are ethnic Czechs. Local women have taken the development of the Bohemka village traditions into their own hands, and now they hope to be able to pass the traditions and customs of Bohemka’s Czechs on to their children.

The first mentions of Czechs on today’s territory of Ukraine go back as far as the 13th century. At that time, their own country was suffering from famine, and many Czechs fled to the neighbouring countries. Over the next few centuries, Ukraine admitted Czech immigrants on several occasions. Czechs moved to Lviv during the period of the Kingdom of Halych and Volyn, because of the town’s important economic and cultural role in Eastern Europe. After the House of Habsburg conquered the Czech territory in the 17th century, the western parts of Ukraine saw a larger influx of Czech migrants. Similar mass migration took place when Catherine II (Catherine the Great), the Empress of Russia, invited Europeans to buy and populate the lands in Crimea. The abolition of serfdom increased the Czech’s level of interest in Ukrainian lands, and so in the second half of the 19th century in Volyn, Podillia, and Crimea, large settlements of Czechs were formed with the rights to establish individual communities and parishes.

The Czech community left quite a noticeable footprint in the history of Ukraine. Its members fought in the Battle of Poltava (between Russia and Sweden — tr.), liberated Ukrainian towns and villages from Nazi occupation, helped to develop settlements in Zakarpattia during Czechoslovakian rule. Today, they continue to be a part of modern Ukrainian history — the history of the Czech community in Ukraine. According to the latest national census in 2001, there were nearly 6,000 Czechs living in Ukraine. The data provided by the Embassy of the Czech Republic in Kyiv shows the total figure of nearly 10,000 Czechs stating that about one-third of them consider Czech to be their native language.

Olha Andrš. The ‘Bohemka’ society

She’s always busy, always hanging onto her phone and is always on the move: walking or cycling between the church, the cultural hall, and her home. Life in the home village of Olha Andrš, head of the Czech society ‘Bohemka’, is in full swing. Especially on Thursdays.

“Thursday is an especially busy day. It’s a market day in Dobrozhanivka, the district centre. People go there to buy or sell things. People also go to the district centre on their own business, because even the local council adjusted its working hours to meet the demand.”

Olha has been involved in the village’s education and cultural development since the 90s. This all started when she went to the Czech Republic to study teaching. As she came back, the Ukrainian SSR she left had become an independent Ukraine. She heard about the dissolution of the USSR from one of her professors. She felt nervous first, because this reminded her of another similar case:

“People in our village told a story: there was a teacher who in 1948 took a group of orphans to the Czech Republic for rehabilitation. The children would spend some time at a camp, and then the teacher would bring them back to the village. But as it happened, the border was closed and that teacher ended up stranded in the Czech Republic. His wife and his children were left in the village, as were the siblings of the orphans who were also stuck in the Czech Republic. The teacher’s family was separated. So, when I heard from our professor that the USSR no longer existed, I became worried: what was I supposed to do then about my husband and three kids?!”

Olha returned to the village, whose old culture had been on the brink of extinction for a very long time, and now had a chance of survival thanks to re-established connections with the Czech Republic. Olha immediately applied to the local council with the request to allow Czech lessons in a village school:

“I presented my diploma which was issued in the Czech Republic and was allowed to teach Czech as an optional subject. The initial financing was provided by the local council. And so, the Czech language has now been taught in our school since 1991.”

slideshow

Olha was born to a Czech mother and Ukrainian father, so she is a master in both languages. The Czech dialect in Bohemka is quite different from standard Czech though. Even local Czechs themselves say they speak more Bohemian than Czech:

“Many words were brought by our ancestors. Some of these words are no longer used in the Czech Republic — they became archaisms. We adopt some Russian or Ukrainian words in our language, although we modify them as if they originated from Czech.”

To make a Ukrainian word sound more Czech, Bohemka residents put emphasis on the first syllable. For example the word ‘rundélyk’ (‘saucepan’), which is a word in the dialect of the region of Halychyna, in Bohemka is pronounced as ‘rúndel’. But that is just one way. The Ukrainian ‘palets’’ (‘finger’) loses its soft ending and turns into ‘paletz’, while in the standard Czech the word ‘prst’ is used.

In addition to giving language lessons, Olha also plays an active role in the life of a female ensemble ‘Bohemske frajerky’. They often perform at Ukrainian festivals and Czech ‘plesy’. Because the ensemble represents the Czech community in Ukraine, it required a formal representative to organise its travels and take part in conferences.

The Czech society in Bohemka had existed formally for years, but its main concerns mostly involved the affairs of the local collective farm and the church. As the ensemble was attending various international events, there was no official representative to speak for Bohemka and its community at meetings and conferences. So during one of the rehearsals, the ladies decided to take the lead and voted for Olha to become their head:

“My back is well covered, and I have plenty of support at home, so I decided not to continue with the existing society but to establish a new one. So, in 2007 we founded the Czech Society ‘Bohemka’.”

Thanks to the Society’s activity, people in the Czech Republic know about their fellow countrymen in Bohemka. A summer camp for children and adults is run in the village, where teachers and students from the Czech Republic give lessons in Czech, run religious classes, and other cultural exchange activities. Children from Bohemka have an opportunity to attend summer camps in the Czech Republic, which increases their motivation to learn Czech at their lessons with Olha Andrš.

Bohemske frajerky

“Ahoj holky!” (“Hello girls!” — in Czech) — the ensemble members greet each other every time they meet. For over 55 years, ‘Bohemske frajerky’ (‘frajerka’ means ‘a trendy dresser’ in Czech) have their rehearsals in the cultural hall. The first cast (which performed under the name ‘Nyva’) collected the songs of old from the times of the first settlers. Olena Hart, a member of the ensemble, tells how the repertoire was formed:

“They had very old books of lidově (‘folk’ in Czech) songs and even records of popular beliefs. And those books were passed down from generation to generation. The non-written songs were also sung by many generations until they were put in writing later.”

The ensemble’s repertoire remains almost unchanged. The ladies do not sing any contemporary songs, only those which were once brought by their Czech ancestors to Ukraine. That is how they manage to preserve their Bohemian culture not only within their own village, but in Ukraine and in the Czech Republic in general. Olha Andrš, who usually starts their performance, supports this view:

“For a long time, our ensemble was considered the village’s major trademark, as there was nothing else known about the place.”

slideshow

Thanks to ‘Bohemske frajerky’, the Bohemka village is well known in Mykolaiv, Kyiv, Kherson, Lutsk. They have performed many times at various international festivals in Ukraine and at Czech national festivals, which gather their fellow countrymen from all over the world.

Tours, festivals, rehearsals several times a week — the ensemble members have enough time and energy for all that bustling cultural life even after their jobs and household chores. As soon as they finish singing, the women rush back to their homes to do their chores, such as milking cows. But they are not alone, Olena reassures:

“Now when we leave to have rehearsals or to perform somewhere, which may take two to three days, our husbands support us and help with the chores. We have strong support within our families.”

The men of Bohemka used to perform too. Olha Andrš recalls a time when along with the female ensemble there was a male one. It was later disbanded:

“Most members of that ensemble were men who served in Ludvík Svoboda’s army during World War II. They brought many songs about liberation.”

Ludvík Svoboda

A Czechoslovakian military officer; under his command the Czechoslovakian brigade of the Ukrainian army liberated Ukrainian towns and villages from Nazi occupation. President of Czechoslovakia in 1968–1975.‘Frajerky’ do not sing any songs about liberation, but in addition to many lyrical ones they have a few that are patriotic:

“We have a song about our ancestors who had to leave their land to look for a better life in other places. We also have one about Jan Hus — about his execution by burning at the stake.”

Songs about ancestors or about Jan Hus are sung on special occasions, such as the village’s foundation day.

The Hussite movement

In the 15th century, monarchy ruled over the territories of modern Czechia. The kingdom of Bohemia, which included the historical regions of Bohemia, Moravia, Silesia, and Lusatia, was subordinated to the Holy Roman Empire and to the Pope himself. Czechs went to Catholic churches where services were given in German, because the Empire was run by the large German dynasties.

Jan Hus — a philosopher and a teacher — did not agree with the Catholic dogmas and advocated the reformation of the church. His teachings were followed by many Czechs, who later became called the Hussites. The Hus followers wanted a more modest life of the clergy, services to be given in Czech, separation from the Pope and the supremacy of the Bible over the church. This was how a new Protestant religious movement emerged — the Evangelical Unity of Brethren.

Czech Brethren

A Protestant Christian movement which emerged in Bohemia in the 15th century as a continuation of traditions of the Hussites revolutionary movement.Jan Hus was arrested and prosecuted. The Catholic Church accused him of heresy, and the secular authority sentenced Hus to execution. The death of Jan Hus sparked multiple Hussite uprisings across the kingdom. The unrest lasted for three centuries. The Pope called the Hussites heretics and sent several crusades against them. In the 17th century, the Thirty Years’ War broke out in Europe between Catholic and Protestant countries. The Battle of White Mountain, which took place in 1620 near Prague, was the Hussite movement’s last breath — when the Habsburgs’ soldiers took over Bohemia, the last leaders of the Hussites were executed in Prague’s town square.

Emilie Andrš, a Bohemka resident, knows the Hussites’ history well, because those were her ancestors who fled Bohemia after that last battle and settled in the neighbouring lands, one of those places being the modern Prychornomoria’s territory.

“In Poland, there’s a town called Zelów. This was where many of the Hussite emigrants stayed. Others stayed in Volyn, and some even settled there. And then they moved further and further away until a small group of them reached these lands (Prychornomoria — ed.). They stayed here for a while because of the low rent for land. They then settled here.”

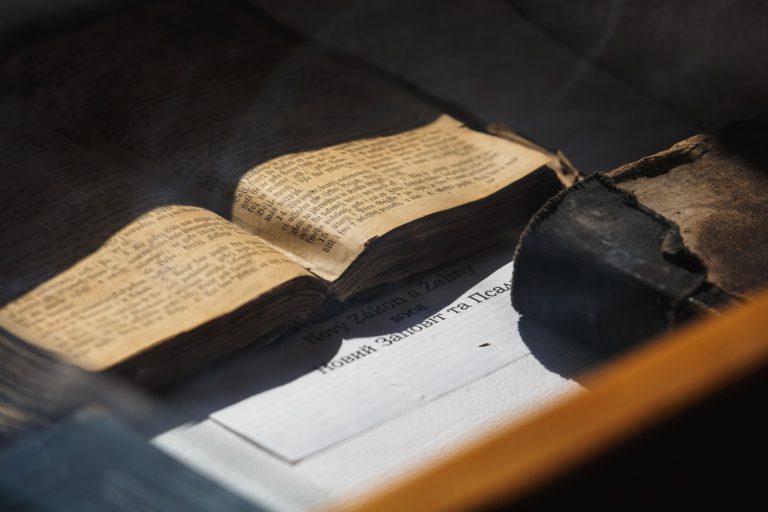

And so those Czechs, who formed the new Protestant movement following the Jan Hus’ teachings, settled in the lands which were free from persecution. Finally, they were able to congregate openly and without any Catholic supervision to read the Holy Scriptures they brought. “They would always have the Holy Scriptures: the Bible or the hymn books (they were called ‘Kancionáls’). The hymn books, I suppose, mostly contained the old German songs translated into Czech”, — Olha Andrš recalls the stories told by the older generation.

This is where the history of Bohemka village began.

Liudmyla Hart. The Bethlehem Chapel

The village’s history can be learned not only from the memories of its residents, but also from the museum which they set up inside the local Bethlehem Chapel — the first Czech Evangelical church in Ukraine, which was established in 1995. Among the exhibits are a painting depicting Jan Hus’ execution, a baptismal font, and various household items of Bohemka residents.

The church also has a library, where there are many modern books in Czech, as well as several Bibles dating to the time of the Thirty Years’ War. The library walls are covered with photos showing the entire history of how the Bohemka’s church was created. When the Czech Brethren were building up the village, they gathered for services in one of the houses, where they also had a Sunday school.

The curator of the church, Liudmyla Hart, says that after World War II the services in Bohemka were banned:

“There was a period after the war, when the church was not giving any services. They could only use the Czech language when they sang at weddings, some celebrations, or burial ceremonies, but there were no church services given.”

The ban lasted until 1991. Thanks to Olha Andrš, who was studying in the Czech Republic that year, the village managed to establish a connection with the Czech Brethren.

“My sister Olha went to Czechia, and so we asked her to go to a church there, to tell them about our church in Ukraine. So the Czech Brethren sent us a preacher, who came to look at what we had here, how we were running things, and so our relationships with the Brethren began.”

A Czech architect, Petr Pirochta, designed the church, and the Ukrainian team brought it to life. Liudmyla’s husband, Josef Hart, was the head of the local collective farm at the time. He managed the building and provided any help and resources he had, and when the church was finally open, he was appointed as the curator, the church’s monitor. Liudmyla was a part of the village majority who helped to build the church:

“With any ancillary work, say, whitewashing or cleaning or anything similar — we asked for the residents’ help. I would get on the bike, cycle around the village asking people to come and help. In this way we were able to find as many volunteers as we needed for the day to do the job. And so we did day after day.”

slideshow

Before the walls of the long awaited church were raised, the Czech Brethren pastors were visiting Bohemka to give services in the local cultural hall. One of those pastors, Vaclav Hurt, has particularly vivid memories of the place: in the cultural hall, where walls were still covered with the portraits of Marx and Lenin, he baptised about 35 people, old and young.

Really, this was up until 1996 that the services were given in a hall decorated with Soviet-era attributes and a banner reading, “We’ve defended peace, we’re going to preserve it”. On 20 October 1996, the parishioners gathered near the cultural hall for the last time to head to the grand opening of the new church. The new church had a large bright hall with large inscriptions in red on its four walls.

“The phrase you could read as soon as you entered was: ‘May God give us mercy and blessing, and let the light of his face be shining on us’. When leaving the church, you could see and feel that ‘God is our light and hope’. On the left-hand side, we had a slightly shortened version of the Decalogue, to make sure all ten commandments would fit and still could be read. And on the right, we had the Lord’s Prayer.”

Every Sunday, the Czech Brethren church would see dozens of parishioners. During Christmas service it was so busy, people were packed like sardines. Since its opening, the church has given its Christmas service to over 170 people at a time. But over the years the situation has been changing. Liudmyla as nobody else recognises these changes:

“These days we have just about twelve parishioners, maximum fifteen. They are mostly women. Men have no time for this, they are eager to work.”

The Bethlehem Chapel has not had a regular pastor for a long time. Bohemka is visited by the Czech Brethren representatives who give Sunday services and run spiritual classes for kids and adults during several months of their stay. The church has several classrooms and accommodation rooms for the Czech guests, as along with the pastors the village is visited by the teachers, who come with a teaching program for the children.

When Liudmyla’s husband quit the curator post, she agreed to take over the church errands. But the church encourages all its parishioners to take on responsibility, especially when there is no pastor for the Sunday service:

“We can just agree between ourselves who wants or who would be able to take responsibility to run a service once or twice per month. We gather every Sunday but the service is given by different people.”

The Czech Brethren church admits any parishioners whatever their faith is: Orthodox, Evangelical, those who speak Ukrainian or Czech. It is purely a matter of one’s inclination. This is what Olena Hart, a Ukrainian who moved to Bohemka from a nearby village, became convinced of.

Olena Hart. One of their kind among Czechs

In the olden days, Czechs followed the unwritten rule to marry only those of their kind. This was their way to preserve their culture, which originated in their native land. The neighbouring villages, understandably, showed interest in the language and traditions of Bohemka residents, so international interactions between them were inevitable. For example the neighbour of the ‘Bohemka’ society’s head, Olha Andrš, is a Bulgarian:

“There are Ukrainians, Moldovans, across the street there lives a Bulgarian; we also used to have Belorussians here. In the olden days, there were about thirteen nationalities living in the village. Today there are only five left: Czechs, Ukrainians, Moldovans, a Bulgarian, and a Russian woman.”

Olena Hart has heard about the neighbouring Czech community ever since she was a child. Driven by interest, she later moved to Bohemka, where she settled and started a family. A Ukrainian-Czech family.

“We knew the Czechs were living here, because we studied together. My friend was from this village, so I was here before several times — to visit her, to look around — and I heard the Czech language. It turned out somehow that I used to hear Czech language since my childhood, I guess since I was ten.”

The specifics of Bohemka residents are that no matter what their nationality is, they all speak or at least understand Czech. After moving to the village, Olena began to learn standard Czech, to read many books in this language, which became available in plenty, as she was a librarian at the Czech Brethren church. Talking to pastors and teachers during summer camp language lessons was very helpful too. Now Olena mostly speaks Czech in her everyday life:

“I now even think in Czech. I don’t just speak Czech, I… Well, it’s… It’s coming from within… I think in this language, so it’s not a problem for me at all.”

Even with her cows, Olena stops them by calling out in Czech, “Stůj!” As the majority of families in Bohemka, Olena’s family runs a small farm with vegetable plots and some livestock. And still amongst all the chores, Olena manages to attend ‘Bohemske frajerky’ rehearsals and Sunday service in the Brethren church, even though she is Orthodox herself.

Such a smooth cultural and linguistic assimilation does not subdue Ukrainian or other communities, quite the contrary, it suggests to unite the efforts and preserve what has been gained, and enriches it with elements from their own cultures. That’s why Olena feels quite comfortable singing the songs of Czech ancestors as part of a female ensemble:

“First of all, I like that the songs sound different. Most of them are very soothing, very melodious songs. But nothing prevents us from singing a Ukrainian song during rehearsals or even at some performances. For example, on Vyshyvanka Day, we may sing ‘Vyshyvanka’ (a name of a folk shirt with embroidery — tr.), on Independence Day or Mother’s Day we may sing ‘Ridna maty moia’ (‘My dear mother’— tr.). In the village, I perceive myself as both a Ukrainian and Czech.”

Answering how she identifies herself, Olena replies: as a Ukrainian Czech. This manifests itself not only in her language, the songs she sings, the way she’s bringing up her children, who speak both languages fluently, but also in her family life, where the harmony of several cultures reigns:

“We may serve some Czech meals or some Ukrainian. I also have about a quarter of Moldovan blood, so we may cook ‘mămăliga’. There’s nothing special about all that.”

Emilie Andrš. Traditions and meals

Emilie Andrš’s family goes back to Bohemka’s origins. Her ancestors named the village after their motherland — the kingdom of Bohemia — which they had to flee. Still among the villagers, other versions of the name’s origin, more imaginative ones, are spread:

“Long ago there was a legend. It was told that the name was formed from ‘Boh’ (‘God’ — tr.) and ‘Emka’ — the name of a girl, together it formed ‘Bohemka’. How close is this legend to reality? Who knows. But it’s being retold generation after generation.”

Descending from the ancient family, Emilie takes great care to preserve Bohemka’s traditions, and tries to pass them on to her children and grandchildren. From the woman’s personal experience, the best way to learn the Czech culture is through tasting its traditional meals:

“We cook ‘kluski’. Our grandchildren like them even more than Ukrainian ‘varenyky’ (boiled dumplings — tr.).”

Kluski is a potato dish. There are many varieties of them, and even women of Bohemka have four different ways of cooking kluski. They inherited their recipes from grandmothers and this is why the amount of ingredients is still measured in ‘half-bowls’ and ‘half-spoons’:

Kluski

A local name for traditional Czech or Polish dumplings made of potato and flour.“These are called ‘half-spoon’ kluski. It’s because you take a spoon, scoop the mass and drop it into the pan. They are made out of raw potato mix.”

slideshow

Another type of kluski is made of boiled and raw potato mixed together. Emilie explains, in the olden days people harvested plenty of potatoes and hence experimented with recipes. These days, whenever possible, they add a bit of potato starch to the mix. At the end of cooking, when kluski are almost ready, a meat gravy should be poured on.

Kluski are considered a festive meal in Bohemka. The Czechs cook them every Sunday after a church service, when children join their parents for a family meal. A chicken stock and some homemade noodles always accompany kluski on a served table. The same dishes are served to guests at some major celebrations such as weddings. For pudding, the Czechs may offer ‘bukhty’ — sweet buns with different types of stuffing:

“In Old Moravia, in Czechia, they also bake bukhty. Those are just buns stuffed with cottage cheese — a type of sweet pastries. Sometimes they contain poppyseeds or nuts. These buns are very typical for the Czech cuisine. Our grandmothers passed these recipes on to us.”

Czech weddings are different from Ukrainian weddings, and not only because of the meals. Brides do not cover their heads, they wear a wreath instead. When the festive table is prepared, men and women work in tandem: some of them cook, some bring dishes to the table. Czechs also have a pre-wedding custom when women come together to help a family prepare all the meals a couple of days before the main event. The helpers used to bring some ingredients too:

“Some time before, people would fill a bowl with some flour, put some eggs on top, put some poultry, and tie this all up in a headscarf. Today they no longer do this.”

Some of the traditions have become modernised in the village, while others remain as things of the past, as the new generation do not consider them appropriate. And yet Olha, despite constantly clinging onto her phone, would rather communicate important news via a handwritten note, because this is how it has been done for years:

“We write a note and send it in four directions, so that neighbours can spread it further. For example, someone has slaughtered a pig and wants to sell some meat. A note would be written and shared among people. Or if someone has died and the funeral is to be held — similar notes will surely be sent.”

From family life to public performances of Czech songs — Bohemka is full of Czech traditions which have been developing for centuries. Local residents are worried that the younger generation will not follow the trend and will forget about their roots. Many young families move out to big cities or abroad — to the Czech Republic. Despite being of Czech origin and being married to a Czech, Emilie Andrš feels a strong bond with Ukraine:

“I perceive myself as a Czech because my parents were both Czechs, I speak Czech, and live in a Czech village. I also perceive myself as a Ukrainian to an extent, because we live in Ukraine and support its traditions, we learn Ukrainian. One culture is dear to us and the other is not alien.”