For centuries, Ukraine was effectively a colony of Russia, with Ukrainian culture constrained and forced to develop under deeply complex and often dramatic conditions. Ukrainian artists faced relentless repression, bans, and persecution from their self-proclaimed “big brother”, leaving them with a stark choice: stay true to their culture, risking their careers and sometimes even their lives; serve the Russian governments, slowly losing touch with their roots; or try to navigate a precarious path between the two. This is why Ukrainian heritage includes many artists whose lives and achievements still await proper re-evaluation. Most importantly, it’s essential to understand the mark Russia left on them at various points in their journeys.

“Big brother”

Is a popular concept in Russian colonial rhetoric that presents Russia as a dominant, protective force exerting control over Ukraine, which is depicted as a smaller, weaker “little brother”.Understanding the complexities of history, uncovering connections, and re-evaluating the past all contribute to addressing colonial traumas. In other words, this is the essence of decolonisation, and Ukrainian art needs it just as urgently as every other area of public life. Within the “Decolonisation” project, Ukraїner brings together experts from diverse fields to explore how Russia has both physically and psychologically subjugated Ukrainians across different historical periods and to discuss pathways for Ukrainians to finally sever all ties with the aggressor state. The first article in this series focused on the repatriation of cultural property, delving into Ukrainian artists whom Russia banned, appropriated, or otherwise silenced in attempts to suppress their talents and stifle their creative recognition.

Ukraїner, in collaboration with the Projector Institute and Tetiana Filevska, Creative Director of the Ukrainian Institute, sheds light on key figures whose lives vividly illustrate the cultural colonisation inflicted by Russia. Studying these artists reveals their vital role in both Ukrainian and global culture, underscoring the pressing need to decolonise perceptions of the nation for Ukraine and the wider world.

Historical roots of Russia’s cultural colonisation

The historical origins of Russian colonialism can be traced to 1721, when the Muscovite Kingdom declared itself the Russian Empire. Unlike classical Western empires, it held no overseas colonies and did not segregate its people along racial lines, complicating global recongition of Russia’s colonial influences and crimes it committed against indigenous cultures. However, Russia did aggressively subjugate neighbouring peoples it deemed “uncivilised”. Over 300 years later, its narratives remain largely unchanged: Russia still seeks to deny Ukrainians and other peoples the right to their own state, culture, language, and identity. Policies such as the Valuev Circular and the Ems Decree, which banned the Ukrainian language and book publishing, along with extensive repression of the Ukrainian intelligentsia and the stigma of inferiority, have left lasting impacts on Ukrainian identity.

The Soviet Union continued Russia’s colonial agenda. Tetiana Filevska, Creative Director of the Ukrainian Institute, describes its purpose:

“Russia’s colonial policy was aimed at restraining and controlling cultural development in the colonies — the sphere where identity is formed and communicated for a particular community, people, or nation. This is precisely why culture is seen as a ‘dangerous’ thing. At the same time, the empire always feeds off its colonies, usurping and depleting their resources, including talent. Undoubtedly, the Russian Empire sought to take the most talented, intelligent, and progressive individuals into its metropolis, and this pattern has recurred across generations — even during Ukraine’s years of independence.”

The Valuev Circular and the Ems Decree

were key Russian imperial policies designed to suppress Ukrainian language and culture. The Valuev Circular (1863) denied the existence of a distinct Ukrainian language and prohibited the publication of Ukrainian-language books, while the subsequent Ems Decree (1876) sought to eradicate the use of Ukrainian entirely from the public sphere.The targeted destruction of the Ukrainian creative class represents an irreparable loss for both Ukrainian and global culture. The creative lives of artists — and often their physical existence — were forcibly and dramatically altered or brought to an end. It was the actions of the Russian Empire and the Soviet Union that prevented them from writing texts, painting, composing music, staging theatrical performances, creating sculptures, and more.

Today, Ukrainians find themselves in perhaps the most intense phase of their war against the Russian Federation, and for them, this conflict is fundamentally about decolonising their culture. As a result, Ukraine’s cultural heritage demands even more thorough research and reassessment to ensure that the enemy is not given any further opportunities to distort or appropriate its artists and their achievements.

When rethinking or introducing an artist into the Ukrainian discourse, it is essential to consider their social and cultural environments, as well as the messages they created, promoted, or opposed. Are there imperial narratives concerning Ukraine present in their works? How did they perceive their own identity, and was this self-identification free from coercion? What were their perspectives and life choices? Understanding the context surrounding any artist is crucial; regardless of our desires, art cannot be entirely separated from the social and political circumstances in which it exists.

Les Kurbas and Mykola Kulish: Ukrainian artists banned by the Soviet regime

The generation of the Executed Renaissance (1920s — early 1930s) serves as a particularly poignant example when discussing banned Ukrainian artists. Approximately 30,000 Ukrainian cultural figures fell victim to Stalinist repression throughout the 1930s. The Soviet Union, as the successor to the Russian Empire, did everything in its power to eradicate Ukrainian art. While repression occurred both before and after Stalin’s era (1924 – 1953), it was during his rule that these efforts reached an unprecedented scale. The Soviets wiped out an entire generation of artists, banning their works and branding them as “bourgeois nationalists” or “enemies of the people” (a propaganda label used by the Soviet authorities against dissenting groups to justify their persecution. – ed.), or even rendering them completely invisible. The Empire simply had no place for Ukrainian art.

Executed Renaissance

was the generation of Ukrainian artists, writers, and intellectuals of the 1920s and 1930s who were exterminated by the Soviet regime to eliminate Ukraine’s national identity and cultural autonomy.

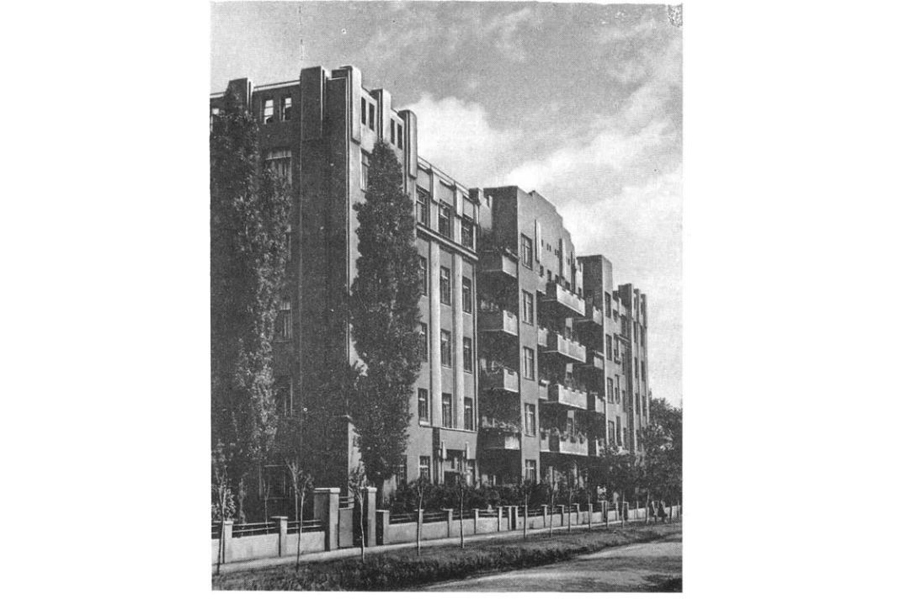

The Slovo Building in Kharkiv, one of the landmarks and symbols of the Executed Renaissance. Photo: proslovo.com.

Ukrainian director Les Kurbas and playwriter Mykola Kulish were only two of many prominent artists of that time, who perfectly exemplify the tragedy of their generation. Both were captivated by contemporary European drama and expressionism, turning away from previous traditions in favour of artistic freedom. Their creative partnership defined modern Ukrainian theatre, introducing new dramatic approaches that shifted away from conventional action-driven narratives to focus on portraying the soul’s existence and inner movements. Kurbas and Kulish, active during the early Soviet era, revolutionised Eastern European theatre with bold innovations in modern drama, establishing themselves as pioneers well beyond the USSR’s borders. For instance, they employed masks to inspire the audience to think and feel through imagery, thus revitalising the classical Greek drama that forms the foundation of European theatre. This was the essence of Kurbas’s experimental Berezil theatre, which served as the foundation for his fruitful artistic collaboration with Mykola Kulish that started in 1926.

Berezil Theatre

was Les Kurbas’s pioneering experimental theatre of Ukrainian modernism, which merged the national traditions of Ukrainian theatre with the latest innovations of European drama.

Ukrainian director, actor, theatre theorist, playwright, publicist, and translator Les Kurbas. Photo from open sources.

Ukrainian writer, director, and playwright Mykola Kulish. Photo from open sources.

Berezil continually pushed the boundaries of theatre, embracing innovation and avoiding traditional ethnographic styles. Les Kurbas was influenced by European trends and, notably, refused to tour in Moscow. Alongside Mykola Kulish, he brought their landmark productions to the stage at Berezil, provoking both admiration and harsh Soviet criticism.

The “Maklena Grasa” performance in the “Berezil” Theatre. Photo: openkurbas.org.

One of their most notable plays, Maklena Grasa, is highly symbolic, posing the poignant question of the artist’s fate in society — a concern that was especially pressing during that period. The staging was notably bleak; in fact, the sun — towards which the main character, Maklena, runs in the original text — was entirely omitted. This production marked Les Kurbas’ final performance at Berezil and Mykola Kulish’s last play. Tragically, both artists were arrested shortly after and executed in 1937 in the Russian tract of Sandarmokh. There are rumours that they were killed by the same bullet.

Sandarmokh tract

A woodland area in the Republic of Karelia, northern Russia, where Soviet secret police executed over 9,000 political prisoners in the 1930s. Around a third of the victims were part of Ukraine’s cultural and scientific elite, severely affecting the country’s cultural development and national identityThese horrific events must be remembered, as they play a crucial role in shaping national memory – the vital component of Ukrainian identity, which the faltering Russian colonialism seeks to obliterate. Today, we can only speculate on how Ukrainian culture might have developed if the Soviet authorities had not systematically eliminated these and other vibrant artists. Tetiana Filevska offers valuable insights into this subject:

“If we imagine that the artists of the Executed Renaissance had survived, I am convinced that today we would not struggle to understand the importance of culture. Ukrainian culture would be robust, globally recognised, and in demand. It would have developed industrially and financially, and would be actively promoted.”

The Soviet authorities took deliberate measures to suppress the creative accomplishments of Les Kurbas and Mykola Kulish within the USSR. They labelled both artists as “dangerous” and deemed their activities a threat to the regime. In 1933, Les Kurbas was not only stripped of his state awards but also expelled from his own theatre. Mykola Kulish faced expulsion from the Communist party, with his works banned. In 1934, he was arrested and falsely accused of being part of a terrorist organisation, leading to his subsequent execution three years later.

In the 1930s, social realism replaced avant-garde experimentation as the only officially accepted artistic method, meaning that cutting-edge Ukrainian innovations in the art world of the 1920s were now deemed “unacceptable”.

Socialist realism

was the officially mandated artistic style in the USSR from 1934 to 1980, in which artists were expected to promote the ideals of the Communist Party and align their work with its ideological goals.Fortunately, despite executing artists and banning any mention of them for decades until the collapse of the USSR, Soviet authorities ultimately failed to suppress Ukrainians’ interest in these creative figures and their work.

The legacy of both artists is still relevant, so contemporaries constantly turn to it. They also make sure that their memory is properly honoured. For instance, over ten settlements in Ukraine now bear the name of once-prohibited Les Kurbas, an academic theatre in Lviv is named after him, and a centre in Kyiv carries his name as well. A theatre in Kherson, a southern Ukrainian city that endured Russian occupation in 2022, as well as several streets in various Ukrainian cities, were named in honour of Mykola Kulish. Additionally, the Kherson Regional State Administration established a regional literary award in recognition of the prominent writer.

Mykola Hohol and Anatol Petrytskyi: Ukrainian geniuses stolen by Russia

Before the Russian Empire seized Ukraine and dismantled its statehood in the 18th century, initiating a 300-year period of colonisation, the country enjoyed a vibrant and flourishing cultural life. Tetiana Filevska reflects on this period:

“We had academies, artists, a vibrant musical scene, and much more, while the Muscovite Kingdom had none of that. To establish imperial greatness, all the best and most developed elements had to be drawn from the province that Ukraine had been reduced to and relocated to the centre. This desire to appropriate everything Ukrainian stems from a widespread feeling of inferiority in the Muscovite Kingdom when compared to Ukraine. Meanwhile, who founded all these institutions in Moscow? Theophan Prokopovych and others like him.”

Theophan Prokopovych

was an influential 18th-century Ukrainian bishop and scholar. Initially an advocate for Ukrainian autonomy within the newsly-established Russian empire, he later became a major ideologist of Russian colonialism, as his work was overshadowed by imperial policies. He also masterminded the renaming of the Muscovite Kingdom to Russia — a term derived from the Greek word for “Rus”, the medieval empire centred in Kyiv.Another significant peril for Ukrainian artists, both under the Russian empire and the USSR, was the issue of identification. They were often mislabelled — and continue to be today: sometimes deemed Ukrainians, other times Russians. Often, this confusion stems from a chauvinistic Russian discourse that seeks to appropriate these artists. However, there are indeed some ambiguous figures in Ukrainian history. A prime example is the renowned 19th-century writer Mykola Hohol, globally known by his Russian name Nikolai Gogol. Tetiana Filevska comments on these challenges of self-determination:

“It is clear that identity is fluid and heterogeneous. A person can redefine themselves throughout their life while simultaneously holding multiple ethnic, cultural, political, and social identities. The Russian imperial appropriation of cultural figures is ill-willed, as it denies this complex variety and recognises only one identity — the Russian — as dominant. A decolonisation approach allows to reveal this complexity of identity.”

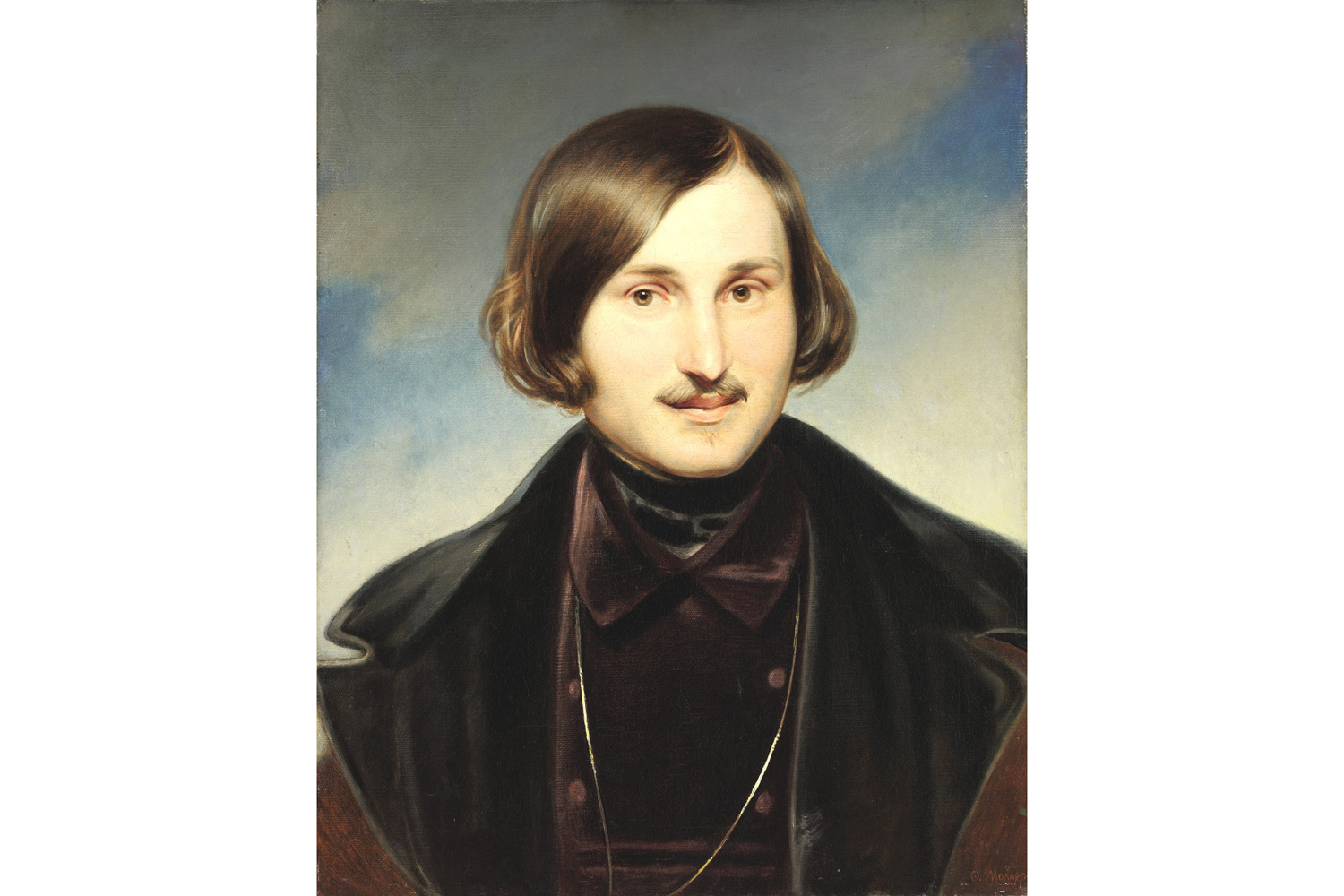

Portrait of Mykola Hohol by Otto Friedrich Theodor von Möller, 1840. Source: Tretyakov Gallery.

Opinions about Hohol vary even within the Ukrainian literary community. For some, he is seen as a writer who made the “wrong” choice by aligning himself with the Russian Empire. For others, he is viewed as a product of his time or even a critic of the empire in disguise. Each of these interpretations is grounded in specific facts from the artist’s biography, literary works, and epistolary writings. It remains challenging to determine which aspect of Hohol’s “split identity” was more pronounced.

However, there is no denying the significance of Mykola Hohol for Ukrainian culture and his place in Ukrainian heritage. Prominent Ukrainian writers and cultural figures consistently regarded him as a Ukrainian writer who simply wrote in Russian. While one can point to instances of Russian chauvinism in Hohol’s work, this was clearly a strategy for survival and adaptation within the Russian Empire. The writer was not a Ukrainophobe. Throughout his life, he researched Ukrainian history and collected folklore, all of which is reflected in his works. For instance, prominent Ukrainian writer and cultural researcher Yevhen Malaniuk admired this quote from Hohol’s story May Night, or The Drowned Maiden:

“Do you know a Ukrainian night? No, you do not know a night in Ukraine. Gaze your full on it. The moon shines in the midst of the sky; the immeasurable vault of heaven seems to have expanded to infinity; the earth is bathed in silver light; the air is warm, voluptuous, and redolent of innumerable sweet scents. Divine night! Magical night!”

*Translated by Claud Field

The “Moonlit Night over the Dnipro River” painting by Arkhip Kuindzhi, 1880. Source: State Russian Museum

No doubt, Hohol did not actively fight for the bright future of the Ukrainian nation and its sovereignty, and he should not be glorified for things he did not do. However, Russians claim him as their own: on the website of the Russian National Library, in numerous encyclopaedias and textbooks, in the Russian-language version of Wikipedia, and indeed in many Russian media outlets, he is described as “a Russian novelist recognised as one of the classics of Russian literature”. There are still insufficient grounds for Russia to categorically “own” Mykola Hohol. It is essential to recognise that life was quite challenging for writers in the empire, as Tetiana Filevska explains:

“Appropriation and depletion of everything Ukrainian allowed Russia to feed on acquired human talents. On the one hand, these were the resources that allowed the empire to move forward. However, at the same time, there is an essential notion here: living under imperial rule implies that you either adapt and accept the identity of the coloniser, or the empire grinds you down and destroys you. The fortune of artists and their influence on Russian culture depended on this very personal choice.”

Over centuries, Russia has mastered exploiting vague discourses like “Russian or Ukrainian writer” to suit its narrative.

Another example of how Russian colonial discourse appropriates Ukrainian talents is seen in the dramatic fate of the world-class artist Anatol Petrytskyi. Although he was not repressed like many of his friends and colleagues, the Soviet Union appropriated and ultimately stifled what was vital to the artist — his talent.

The cover of the “New Art” magazine with a self-portrait of Anatol Petrytskyi. Photo from open sources.

Anatol Petrytskyi studied under prominent Ukrainian artists Oleksandra Ekster and Vasyl Krychevskyi, emerging as a true star of Ukrainian art in the 1920s and a genius of the Ukrainian avant-garde. The artist constantly challenged himself across various fields, including theatre, easel art, book illustration, and working in the editorial office of the Literary Fair magazine. His works, infused with the movement and rhythm of the times, also showcased vibrant national colours. In 1930, Petrytskyi’s painting Disabled, which commemorates World War I, was selected for the 17th Venice Biennale, an international exhibition of contemporary art.

Painting “Invalids” by Anatol Petrytskyi, 1924. Source: National Art Museum of Ukraine.

In Disabled, Petrytskyi depicted the consequences of World War I. This work resonated in post-war Europe and achieved considerable success. After the biennale, it was included in an international exhibition that travelled to Berlin, Bern, Geneva, Zurich, and even New York. Collectors expressed interest in purchasing the painting, but Anatol Petrytskyi believed it should be returned to Ukraine. Ultimately, it did return, but in the Soviet Union, his artwork faced a very different reception. After socialist realism was established as the only officially approved artistic method, the Soviet authorities accused avant-garde art of formalism and distorting reality, claiming it posed a threat to the new society.

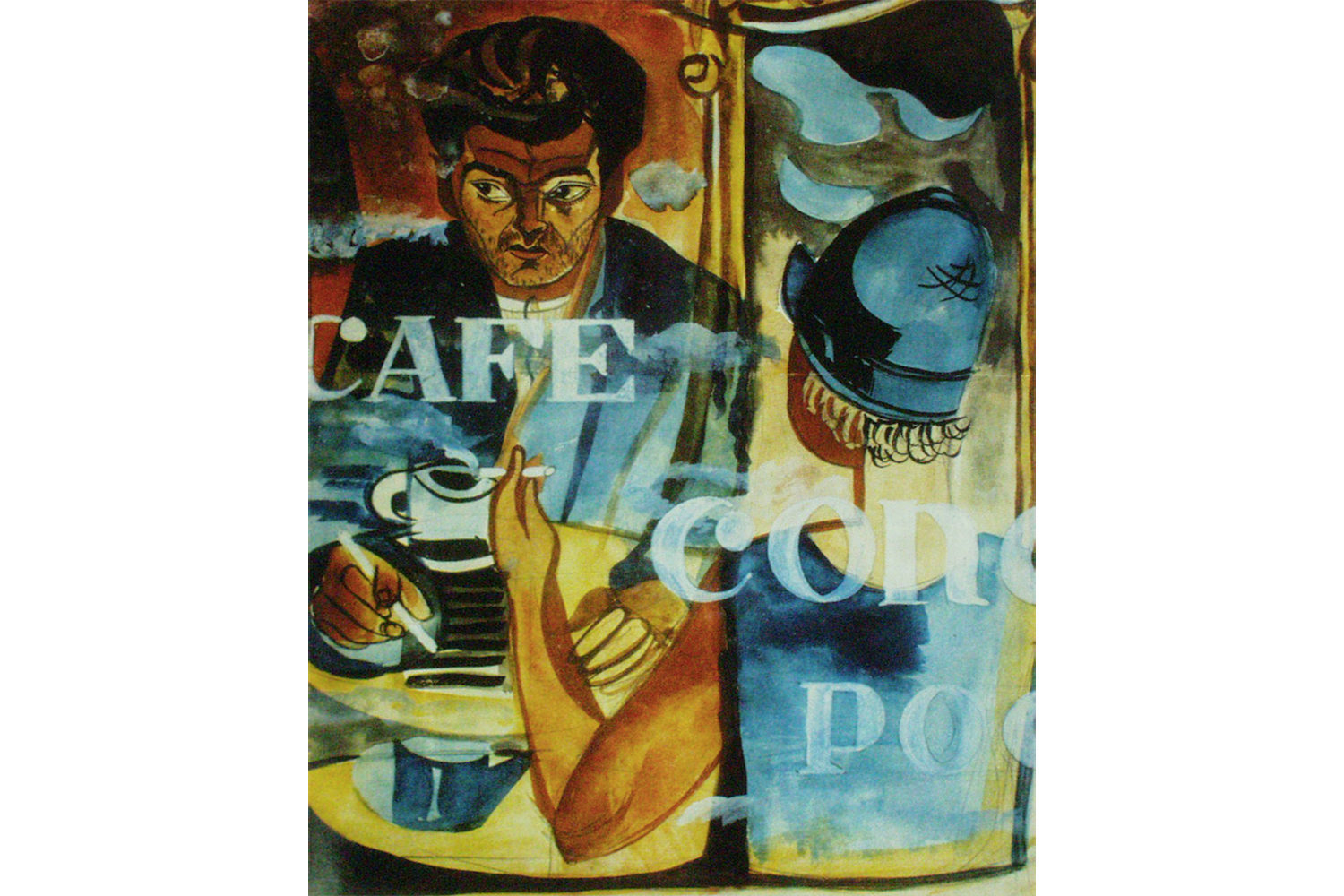

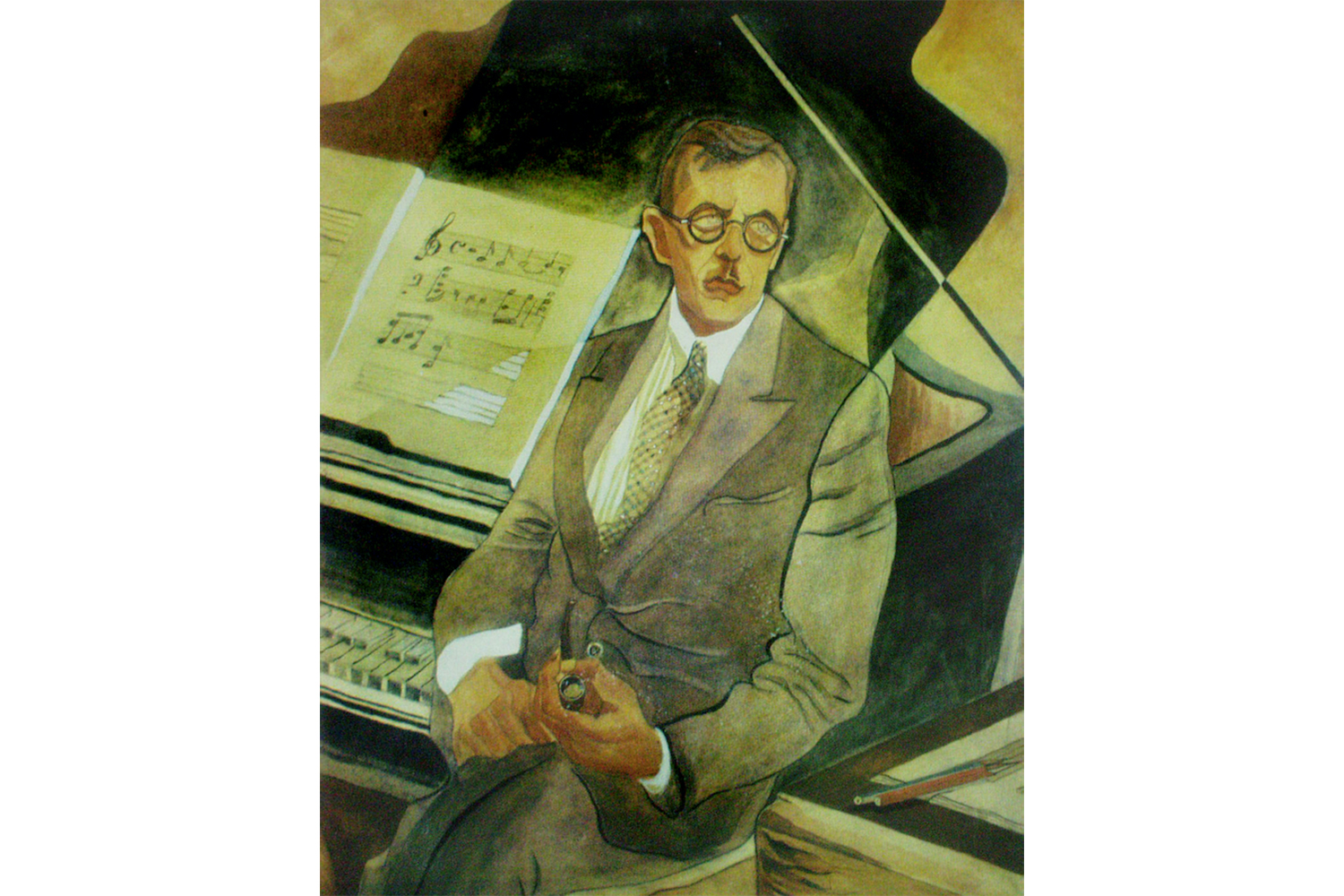

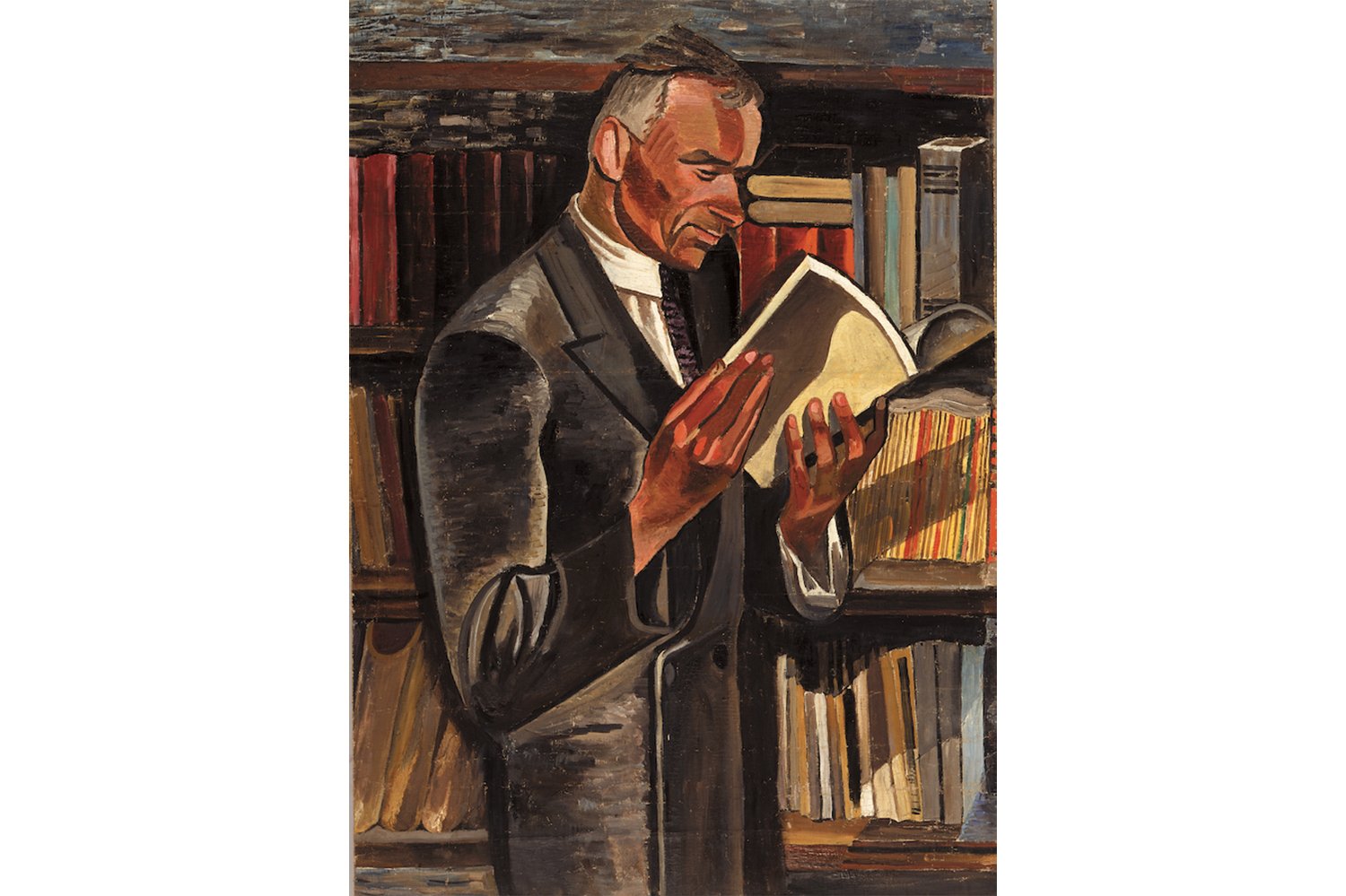

Thus, modernism, which had been permitted and even promoted in the newly established USSR during the 1920s as a way to break from “bourgeois” academic art, became a source of repression for Ukrainian artists in the 1930s. The same fate befell Anatol Petrytskyi, who lived and worked in the Slovo Building in Kharkiv, where most of its residents ultimately perished in Stalin’s Great Terror. In the 1920s, he created a series of portraits of writers, playwrights, and artists who would later be sent to labour camps or executed in the following decade. Not only did the regime wipe out these artists, but it also caused many of their portraits to be lost. Out of more than a hundred portraits by Petrytskyi, only a dozen have survived to this day. Their story serves as a reminder of the destroyed generation of Ukraine’s intelligentsia and reveals the challenge of preserving its historical memory under the pressure of Russia’s continuous violence and more subtle forms of colonial influence.

The Slovo builduing

a landmark in Kharkiv, the first capital of Soviet Ukraine, that served as a hub for the Ukrainian avant-garde elite in the 1920s. Following Stalin’s ideological shift in the 1930s, most residents faced repression, and their works remained banned until the USSR’s collapse in 1991.

Portrait of Mykhail Semenko by Anatol Petrytskyi, 1929. Source: National Art Museum of Ukraine.

Portrait of Pylyp Kozytskyi by Anatol Petrytskyi, 1931. Source: National Art Museum of Ukraine.

Portrait of Hordii Kotsiuba by Anatol Petrytskyi, 1925-31. Source: National Art Museum of Ukraine.

Unlike most Ukrainian artists and writers of his time, Anatol Petrytskyi miraculously escaped repression — he lived to the age of 70 and even adapted to the new realities of the USSR. However, the tragedy of his fate lies in the fact that he had to deny his true self. The avant-garde explorations, rhythm, movement, sound of the new era, national colour, and world recognition — all of this remained in the 1920s. Anatol Petrytskyi passed away burdened with difficult emotions and a sense of defeat. This is poignantly illustrated by a story from the memoirs of Ukrainian artist Tetiana Yablonska:

“In 1952, I visited Kraków [in Poland] and, fuelled by my youthful communist enthusiasm, convinced the Kraków abstractionists of the merits of socialist realism. Upon returning to Kyiv, I shared my views on the decay of Western culture with Ukrainian artists. Petrytskyi approached and challenged me: ‘Why are you talking about things you don’t know?’ I felt ashamed. The next day, at a communist party meeting where he was to speak as a local party unit secretary, Petrytskyi used my own words to denounce the ‘rotten West’ from the rostrum.”

The work by Anatol Petrytskyi: a sketch of the theatre costume for the “Turandot” opera, 1928. Source: Museum of Theatre, Music, and Cinema of Ukraine

Sketch of the costume for the “Vii” performance, 1925. Photo from open sources.

Sonia Delaunay and Oleksandr Arkhypenko: forgotten Ukrainian artists in exile

It is also important to acknowledge those artists who chose the path of emigration. For many, emigration was not a dream but a necessity, as they were forced to flee in order to survive and escape the Soviet system, which sought to destroy both their identities and their art.

In Ukraine’s history, there have been four waves of emigration (1880–1920; 1920–1930; 1940–1954; 1987–2014, and in some sources, to the present day). The years of condemnation and silencing of Ukrainians, who were known and respected worldwide by Soviet authorities, present Ukrainians with another decolonisation task — the awareness of the full extent of Ukrainian cultural heritage.

One of these artists in exile was Sonia Delaunay. In the early 20th century, life brought the artist and designer from Odesa in souther Ukraine to Paris, and consequently, during Soviet times, her achievements were rarely, if ever, mentioned. Her name was known only to a narrow artistic community within the Soviet Union, while in France, Delaunay enjoyed considerable success.

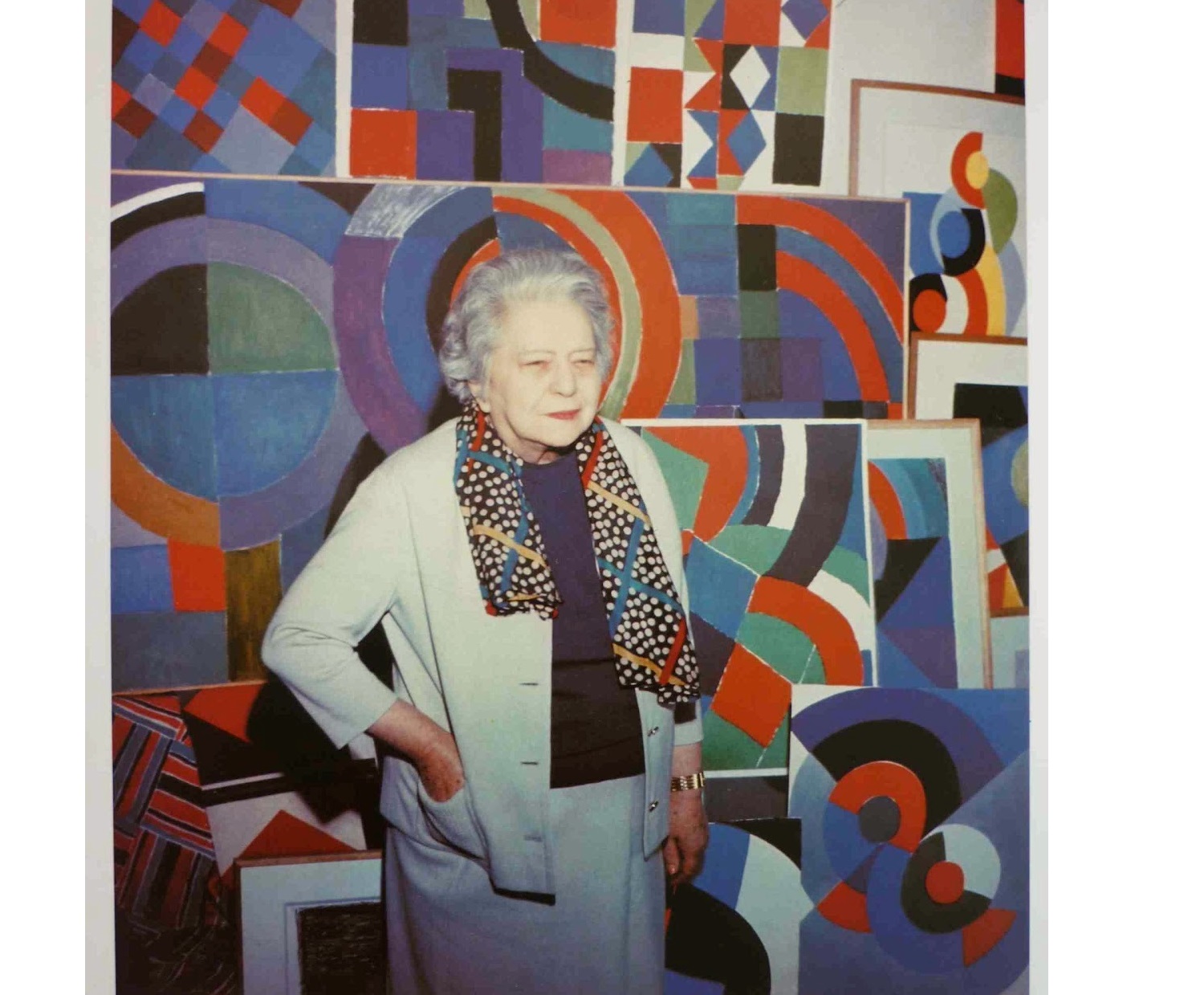

Sonia Delaunay and her works. Photo from open sources.

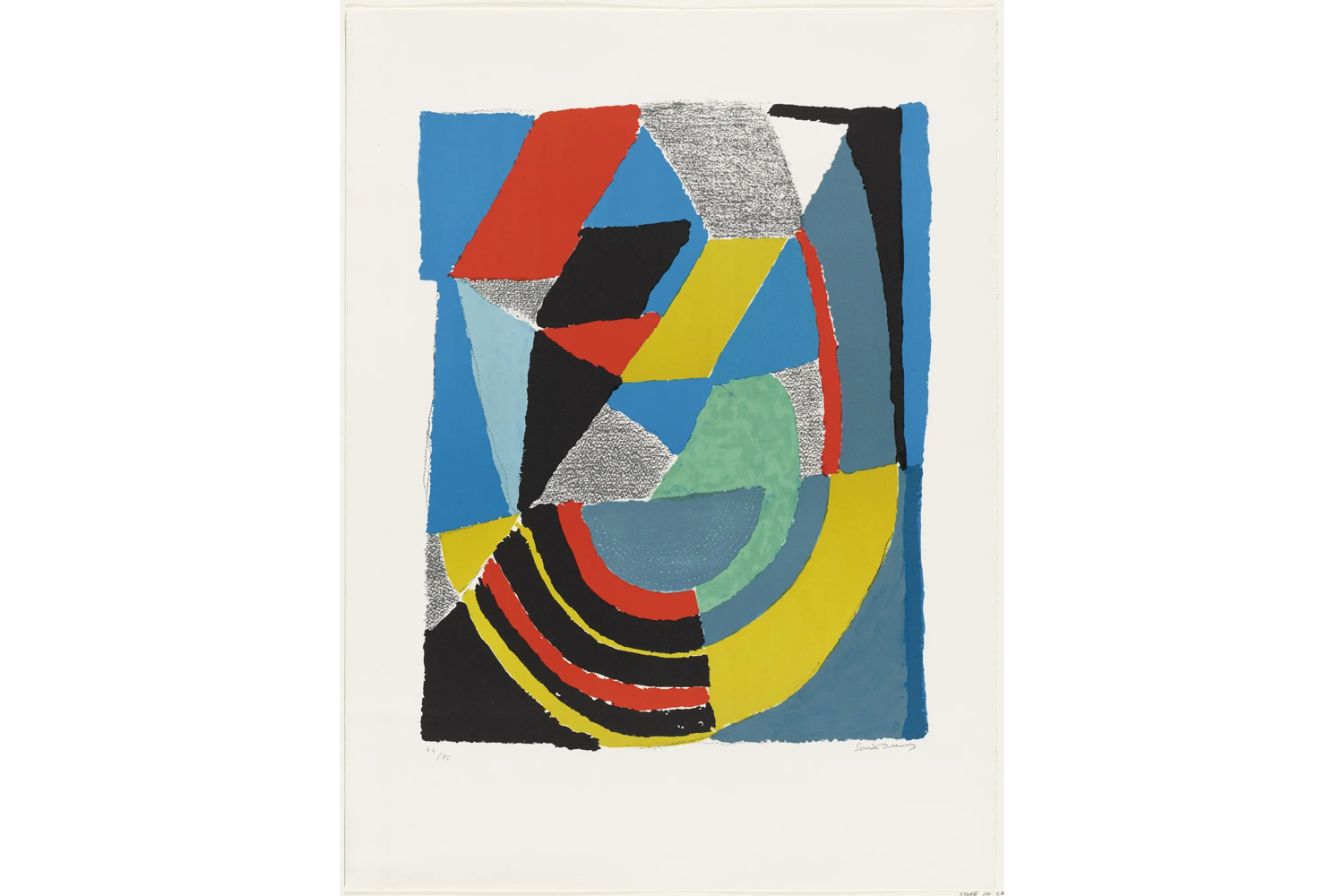

Sonia Delaunay was the first woman in the world to have a personal exhibition at the Louvre. Her works are now housed in the permanent collections of prestigious institutions such as the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York City and the Centre Pompidou in Paris. She became one of the most influential artists of the 20th century and a trendsetter in the art world. Together with her husband, Robert Delaunay, she developed a distinctive artistic style known as Simultaneism, or Orphism, a term coined by the French poet Guillaume Apollinaire.

Sonia and Robert Delaunay. Photo from open sources.

The couple asserted that simultaneism represents the depiction of the movement of colour in light. They created concentric coloured circles and other geometric shapes that, through their composition, conveyed a sense of dynamics and collective action.

Sonia Delaunay’s painting "Rhythm", 1938. Source: Centre Pompidou

Sonia Delaunay’s painting “Composition”, 1977. Source: MoMA.

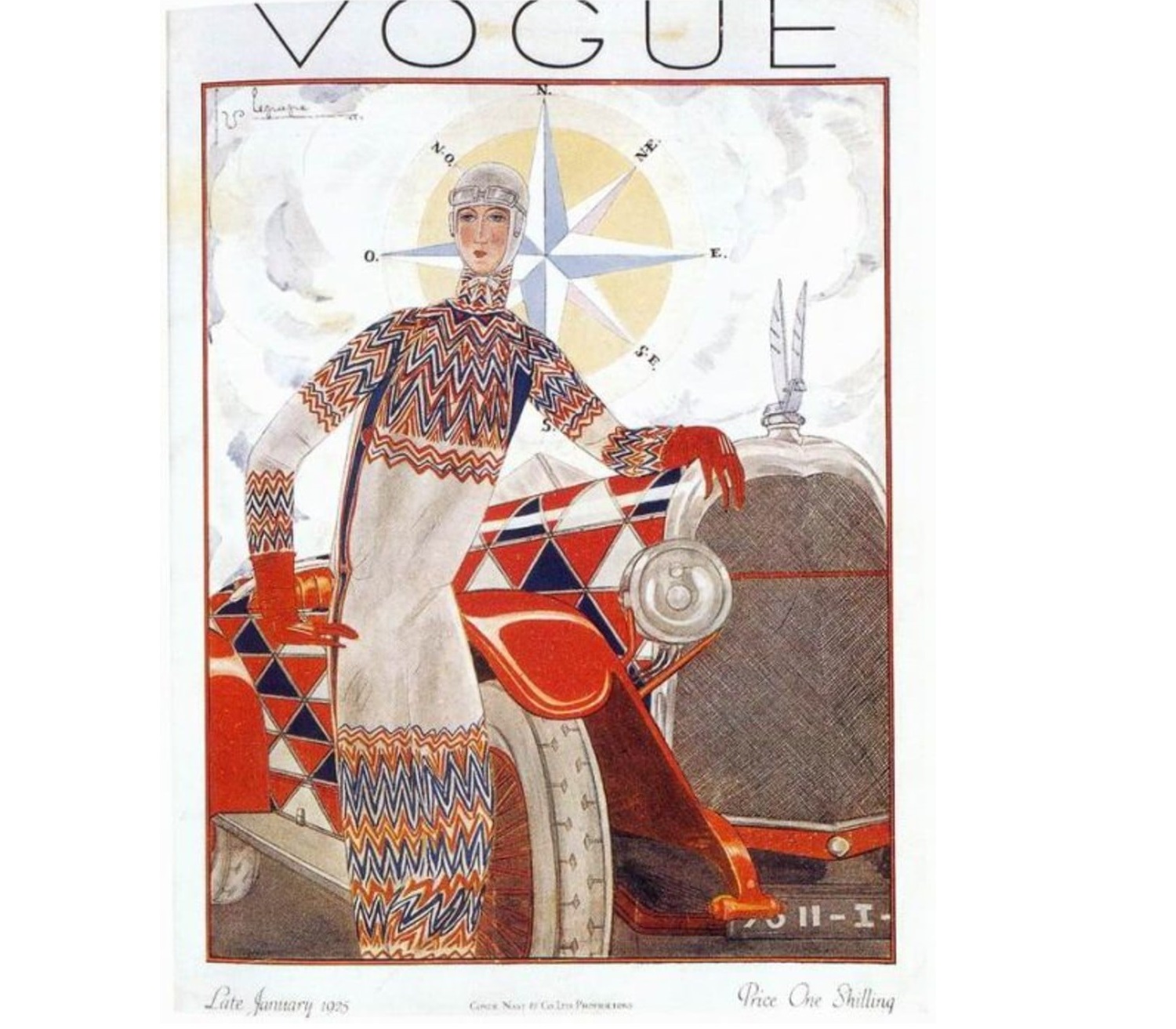

Sonia Delaunay extended the concept of simultaneism beyond canvases into the realm of applied arts. She designed clothing and footwear, theatre costumes, fabrics, and carpets for French factories. Additionally, she illustrated books, worked on ceramics and stained glass, and even decorated cars.

British Vogue cover (1925) featuring Sonia Delaunay’s “simultanic” dress. Photo from open sources.

Certainly, while Sonia Delaunay lived in France and was inspired by that cultural environment, art critics unanimously recognised the Ukrainian elements in her work. She never forgot her roots; in her memoirs, she wrote, “I love bright colours. These are the colours of my childhood, the colours of Ukraine.” Therefore, Sonia Delaunay’s oeuvre is of great significance to Ukrainians, representing an important aspect of Ukrainian heritage.

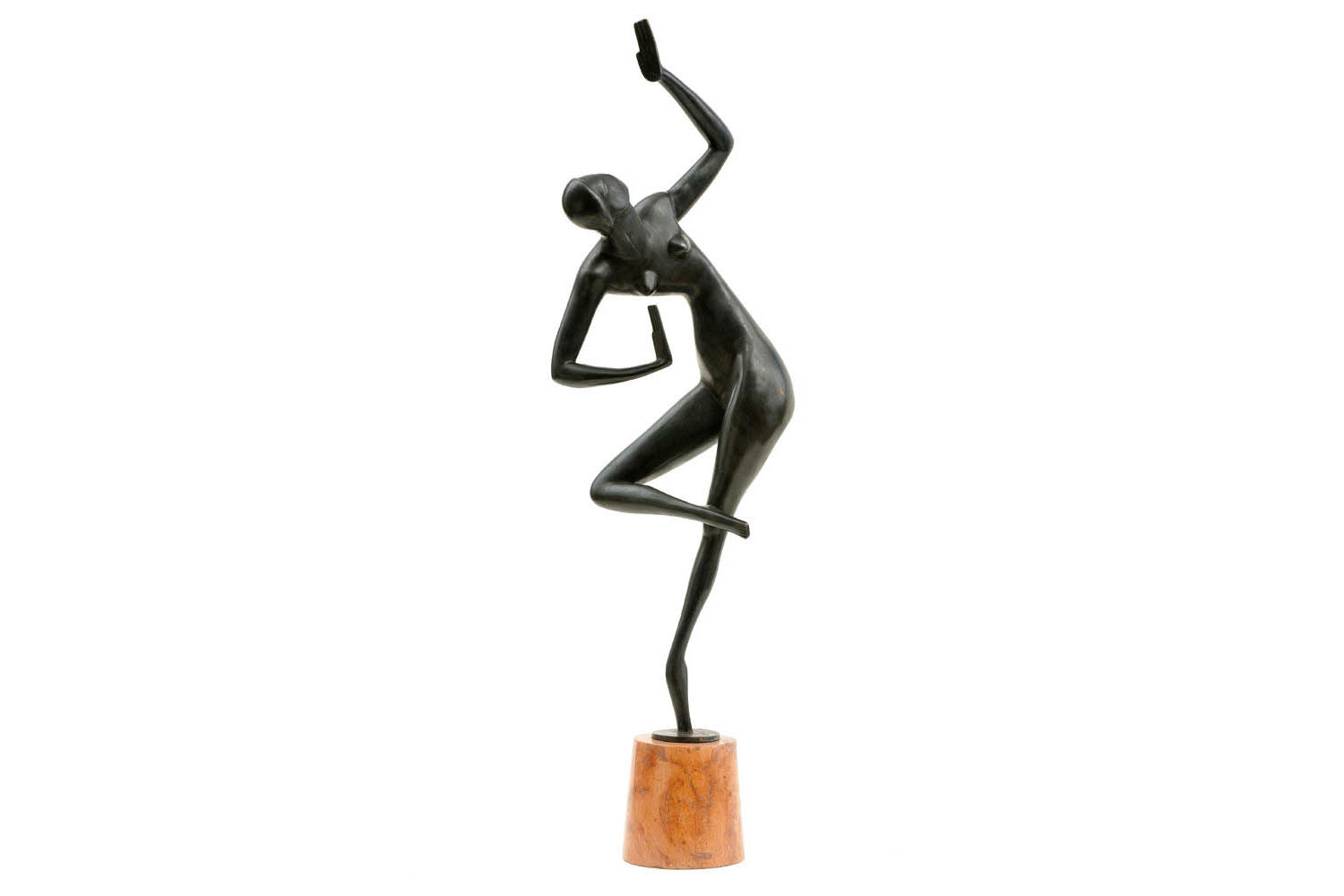

Oleksandr Arkhypenko, a sculptor, painter, and graphic artist, is another renowned creator originally from Ukraine. He is considered the founder of Cubism in sculpture and was the first Ukrainian to participate in the Venice Biennale in 1920. While he gained international acclaim and recognition for his innovative work, his name remains relatively unknown to the public in Ukraine.

Cubism

An avant-garde art movement, which emerged in the 20th century and was characterised by the emphasised geometric shapes of the depicted objects.

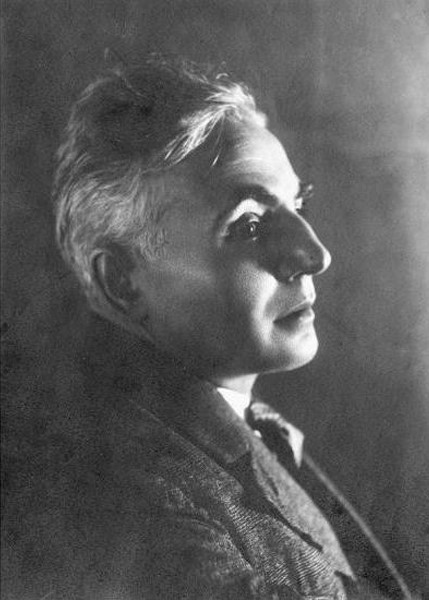

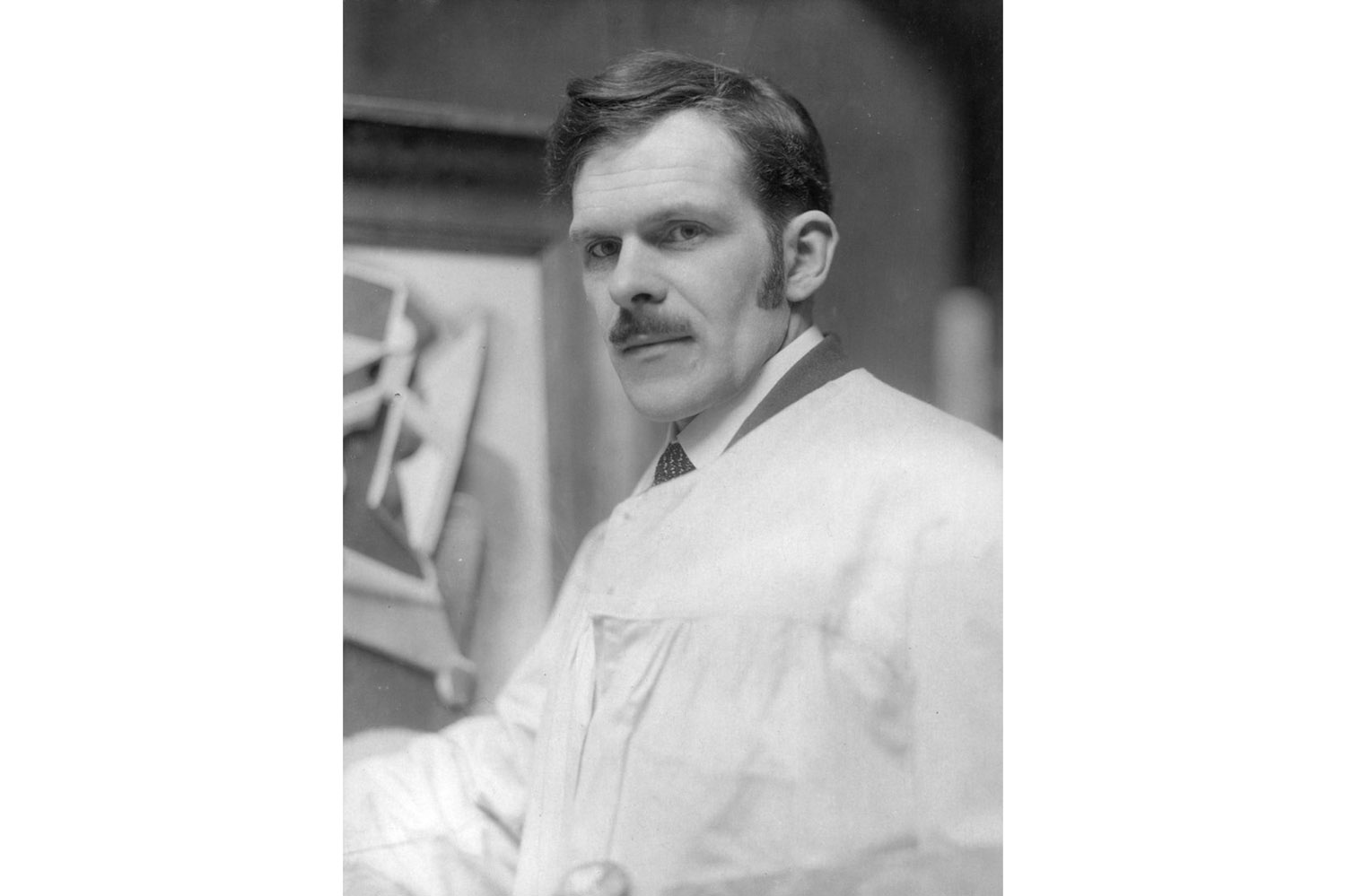

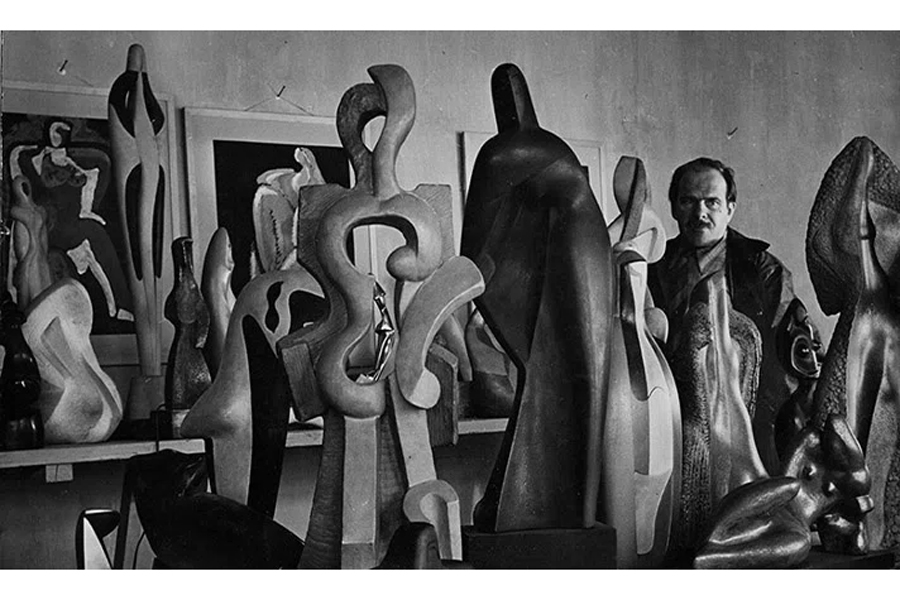

Oleksandr Arkhypenko, sculptor, painter, and graphic artist. Photo from open sources.

Oleksandr Arkhypenko was born in Kyiv and initially studied in Moscow before moving to Paris, where he continued his education at the Paris Art School. He later ventured to Berlin and ultimately settled in the USA, where he became deeply involved in the dynamic artistic life. Not only did he adapt to this new environment, but he also brought about lasting changes within it. Oleksandr Arkhypenko’s name rightfully belongs alongside those of renowned artists such as Henri Matisse, Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque, Fernand Léger, and Kazimir Malevich. His innovative work had a profound influence on the evolution of modernist art across the globe.

Sculpture by Oleksandr Arkhypenko, “Woman Combing Her Hair”, 1915. Source: Tate Modern, London.

The artist was among the first in the world to explore the expressive potential of the “zero” shape, a universal form. He worked not only with tangible materials but also engaged with space as a concept, recognising it as the absence of everything. However, he understood that this absence was not devoid of expressive possibilities; rather, it could complement other objects in significant ways. A striking example of this is the space beneath the woman’s hand in his sculpture “Woman Combing Her Hair” (1915).

Oleksandr Arkhypenko invented a new form of relief carving, which he termed skulptomaliarstvo (Ukrainian for sculpture-painting). He also discovered and articulated the principles of movable painting. Additionally, he created the archipeinture, a unique and innovative mechanism for its time. This device featured a special mechanism that scrolls coloured strips to create a continuously evolving image, generating an illusion of movement. This principle is akin to how today’s advertising billboards with variable images operate. Contemporary sculpture and design would be unimaginable without the influence of Oleksandr Arkhypenko’s inventions.

Sculpture by Oleksandr Arkhypenko, “Blue Dancer”, 1913. Source: Christie's London.

Sculpture by Oleksandr Arkhypenko, “The Gondolier”, 1914. Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Despite achieving success abroad, Oleksandr Arkhypenko remained connected to his roots. He participated in exhibitions alongside Ukrainian artists and became a member of the Lviv Association of Independent Masters of Ukraine. In 1934, he demonstrated his commitment to his homeland by donating his sculpture The Past to a charity auction aimed at supporting fellow Ukrainians suffering from famine during the Holodomor.

Holodomor

was a man-made famine in Soviet Ukraine, orchestrated by Joseph Stalin’s regime from 1932 to 1933 to enforce collectivisation on the Ukrainian peasantry, which resulted in the deaths of 3.5 to 7 million people.

Oleksandr Arkhypenko in his studio. Photo from open sources.

Arkhypenko “returned” to Ukraine only in 2004, when an exhibition of his works was held in Kyiv. Today, the artist’s sculptures are housed in the collections of the National Art Museum of Ukraine and the Andrey Sheptytsky National Museum of Lviv. However, there remains significant work to be done in reappropriating Arkhypenko’s legacy, particularly in overcoming Russian cultural appropriation. It is essential for Ukrainians to ensure that he is firmly rooted in Ukrainian culture and no longer perceived solely as an American or Russian artist abroad.

The case of Oleksandr Arkhypenko exemplifies the challenging conditions faced by free-thinking artists in the USSR, where authorities successfully isolated the Soviet populace from the broader international context. This isolation was so effective that the names of many outstanding native artists remained largely unknown to the public.

How Ukraine can overcome the legacy of Russian Colonialism

One can only imagine how Ukrainian culture might have evolved without Russian interference. Kurbas and Kulish would certainly have staged more brilliant plays together; perhaps Hohol would not have experienced such a profound identity conflict, and Delaunay would have visited Ukraine, leaving her artworks as a legacy. However, we shall never know. Ukraine’s objective is to explore that history and do everything possible to prevent such atrocities from recurring. The first step lies in understanding the reasons behind the systematic devaluation of our culture. Tetiana Filevska outlines these reasons:

“Apparently, Ukrainian culture, its importance and recognition were diminished [by Russia] on purpose. During the time of Kozak statehood, a rich culture flourished in Ukraine, and in medieval times as well. However, today, few people have heard of it outside of specialist research circles. This silencing and downplaying were carried out to erase the foundations for the Ukrainian struggle for sovereignty. Understanding the basic human rights that derive from one’s identity and uniqueness — the right to be oneself, to live according to one’s own will and one’s idea of life, and to realise oneself — all of this is rooted in knowing who you are and who your ancestors are.”

Kozaks

a warrior social class and democratic military entity that emerged in the 16th century in present-day Ukraine, primarily for the purpose of frontier defence. They played a crucial role in shaping Ukrainian statehood, cultural identity, and national self-determination.Research is the most crucial aspect of the decolonisation process. It involves working with archives, conducting research, producing films, publishing books, and organising relevant exhibitions, all aimed at filling the cultural gaps left by colonialism. There should also be public-facing educational projects, including media and social media content, festivals, and visible markers of Ukrainian culture in public spaces, such as tourist routes and commemorative plaques. As Tetiana Filevska highlights:

“When we place culture at the bottom of our priorities — especially in politics and funding — we play into the hands of the enemy. This underestimation is rooted in the imperial policies of the past: oppression, repression, and devaluation. It has been the Russians who, for centuries, have sought to make us think dishonourably about our culture — the most vital aspect of our identity.”

The Ukrainian government should actively support decolonisation efforts. Tetiana Filevska emphasises the need to create appropriate conditions for research and discussion, as well as a safe space for the coexistence of various dimensions and aspects of memory:

“Decolonisation grants everyone the right to memory and forgiveness. Therefore, the government must develop policies that acknowledge people’s pasts, even when those pasts are intertwined with previous political regimes and their crimes. This is a challenging task, one that many may be reluctant to take on, but we have no choice; it is inevitable.”

However, Ukraine’s achievements are already impressive. Since 2023, for instance, Kyiv has finally honoured Oleksandra Ekster, a world-renowned avant-garde artist who spent around 30 years in the city, by naming a street after her. Additionally, foreign museums are gradually beginning to decolonise their narratives around Ukrainian artists. Notably, in the same year, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York acknowledged Arkhip Kuindzhi, originally from Mariupol, as a Ukrainian artist rather than a Russian one.

Oleksandra Ekster's painting “Bridge. Sevres”. Source: National Art Museum of Ukraine.

Ukrainians must engage in a deep reflection on their identity, carefully distinguishing between what is authentically theirs and what was imposed by the empire. In doing so, it is essential to reclaim and restore what has been forgotten or lost. This is the only path to uncovering the true essence of a culture that has been colonised.