The Revolution of Dignity is widely considered the starting point of the revival, or “new wave”, of Ukrainian documentary filmmaking. The need to film events on the Maidan, particularly the crimes of the security forces of the then-president, and the rapid growth of national consciousness catalysed the development of young artistic associations and productions. Their work laid the foundations for a new era of Ukrainian documentary cinema, which continues to this day.

As a result of Russia’s full-scale invasion, the demand for documentary films continues to grow. Ukrainian filmmakers document combat actions, chronicle civilian life, and share their families’ stories. They work with archives, exploring the experiences of previous generations. Simultaneously, film festivals in Ukraine are developing as platforms for finding audiences and sponsors. One of the largest is the Docudays UA International Human Rights Documentary Film Festival.

In this article, we look at how Ukrainian documentary filmmaking has changed over the past century and discuss its current state with young directors whose works were presented at the Docudays UA festival in 2024. These include A Picture to Remember by Olga Chernykh, Under the Sign of the Anchor by Taras Spivak, Intercepted by Oksana Karpovych, and Elevation by Maksym Rudenko.

The origins of of Ukrainian documentary cinema

Like in other countries, Ukrainian cinematography started with documentary chronicles. In 1893, Yosyp Tymchenko, an inventor from Odesa, created a mechanism that became a precursor to the cinematograph. To explore the device’s capabilities, he filmed two one-minute pictures: Spear Throwers’ and Horsemen. However, Tymchenko’s invention did not interest entrepreneurs, and he lacked the funding to produce it himself. Since he couldn’t obtain a patent for the cinematograph, he focused on other scientific fields. Despite its revolutionary nature, his discovery did not gain the same popularity as the Lumière brothers’ cinematograph after 1895. Tymchenko’s apparatus was long part of the collection of the Moscow Museum of Applied Knowledge (now the Polytechnic Museum) under the name “The First Cinematograph for Filming, Printing, and Showing Films”, but its current fate is unknown.

Kinetoscope

A cathode-ray tube designed for reproducing television images. It is used in television receivers, monitors, indicators, and other radio-electronic devices.

Yosyp Tymchenko. Source: Wikipedia

A few years later, in 1896, Kharkiv photographer Alfred Fedetskyi created the first documentary film in the Russian Empire (which, at that time, occupied the territory of Ukraine — ed.). It was 1.5 minutes in length. From his window, he filmed a procession of Orthodox believers carrying the Ozerianska Icon of the Mother of God to The Pokrovskyi Monastery Cathedral in Kharkiv. This and other subsequent films by Fedetskyi were short in duration and had descriptive titles, such as Cossack Horsemanship of the First Orenburg Cossack Regiment, Review of the Kharkiv Station at the Moment of Train Departure with Officials on the Platform, Folk Festivities on Horse Square in Kharkiv, and so on.

Alfred Fedetskyi. Source: polish-kharkiv.com.ua.

Unlike Tymchenko, the documentarian succeeded in commercialising his work. His first public film screenings were held at the Kharkiv Opera House in December 1896. To advertise his photo studio, Fedetskyi organised film shoots and screenings, and he also conducted one of the first live-action film shoots in the Russian Empire — a magician’s performance on a theatre stage. Similar experiments with imagery were being conducted in France at the time by Georges Méliès, the father of live-action cinema — a type of cinematography built around the performances of live actors.

Development of newsreels in Ukraine

At the beginning of the 20th century, newsreel filming became common. This was because French film equipment companies Pathé and Gaumont viewed the Russian Empire as a promising market for films and equipment, as well as for providing cinematographic services. Photo studio owners, film entrepreneurs, and photographers became the first documentarians. Danylo Sakhnenko, a film mechanic and correspondent for the Pathé newsreel, began working in Katerynoslav (now Dnipro) in 1908. In early December, he filmed his first newsreel story, “The First Case of Cholera in Our City”. Between 1908 and 1915, Sakhnenko shot more than twenty documentary episodes in Katerynoslav. He is also considered the creator of Zaporizhian Sich, the first Ukrainian live-action film.

Frame from the film Zaporizhian Sich. Source: gorod.dp.ua.

At that time, film content was already being censored. For example, the film The Beilis Case (1913), produced by Pathé, was banned in the cities of the Russian Empire. The film was about the scandalous Kyiv trial of Menachem Beilis, a Jewish man who was falsely accused of ritual murder.

During the Ukrainian War of Independence (1917–1921), many newsreel recordings were made in Ukraine, often commissioned by various governments. During the year of independence of the Ukrainian People’s Republic (1918–1919), documentarians managed to capture several significant events, making films such as Kyiv During the German Occupation (commissioned by the Central Rada government), Hetman Pavlo Skoropadskyi Attending a Prayer Service in a Kyiv Church on the Feast of Saint Volodymyr (commissioned by Skoropadskyi’s government), The Entry of the Directorate (commissioned by Symon Petliura’s government), and Burial of Young Heroes of Ukraine. Under the command of Nestor Makhno, a Ukrainian political and military leader and well-known anarchist, the Revolutionary Insurgent Army of Ukraine also had its own cinematographer.

The Ukrainian War of Independence (1917-1921)

The key driving forces of this revolution were the Ukrainian people and their political elite, who applied ideas of political autonomy from the Russian Empire to the realisation of their own state independence. A national movement started developing in all regions of Ukraine. Ukrainian government bodies, political parties, and public institutions were created and operated, and culture was being revived. The revolution resulted in the establishment of the independent Ukrainian People’s Republic, which lasted until 1921.After the Ukrainians’ defeat in the Ukrainian War of Independence, most of the territories of modern Ukraine became part of the Soviet Union. The Soviet authorities considered cinema the most important of all the arts, as it could most easily convey communist propaganda to citizens without a proper education. Thus, documentary films became a form of official news information. In the early 1920s, films about the reconstruction of the country after the Ukrainian liberation struggles of 1917–1921 were popularised. Some of these films were titled Restoration of Water Supply, Buildings, and Trams by the Odesa Provincial Communist Department; The Restored Jute Factory; and Revived Agriculture of Ukraine. From 1922 to 1930, three film studios — in Odesa, Yalta, and Kyiv — operated under the All-Ukrainian Photo Cinema Administration. These studios became the training grounds for a new generation of Soviet filmmakers.

The Great Avant-Garde in Ukrainian Documentary Cinema

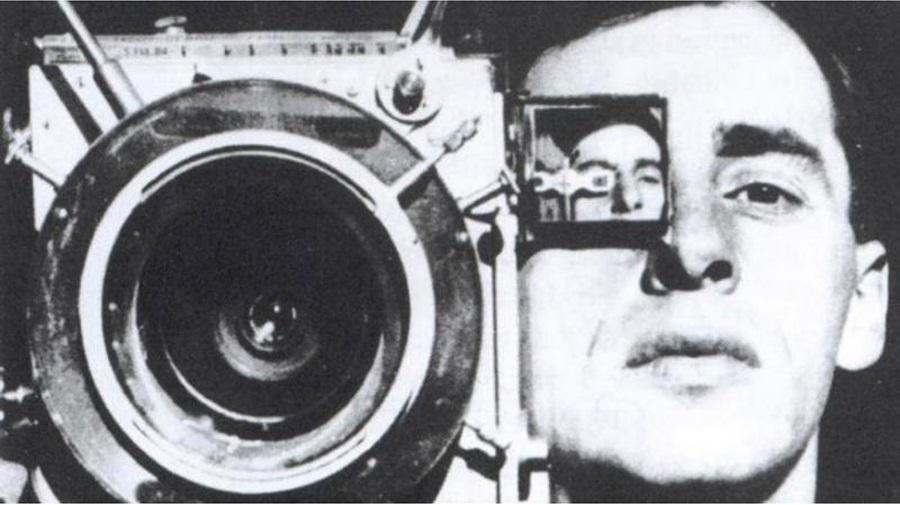

One of the young documentarians who made a name for himself while working at these studios was Dzyga Vertov, an avant-garde director and the founding theorist of Ukrainian documentary cinema. In 1919, he created the “Kinoky” (Kino-Eye) association along with his wife, editor Yelyzaveta Svilova, and his brother, cinematographer Mykhailo Kaufman. The name was derived from the director’s belief that the camera is more objective than the human eye and can therefore better capture reality.

Dzyga Vertov. Source: ikitb.knukim.edu.ua.

To create “pure cinema”, the “Kinoky” group rejected the influence of traditional arts such as literature, theatre, and music. Their platform for creative exploration became the “Kino-Pravda” party newsreel (1922), where young documentarians honed their artistic visions and practical skills. While producing 23 episodes chronicling the early years of the USSR, Vertov first employed techniques and methods that would later become integral to his cinematic language.

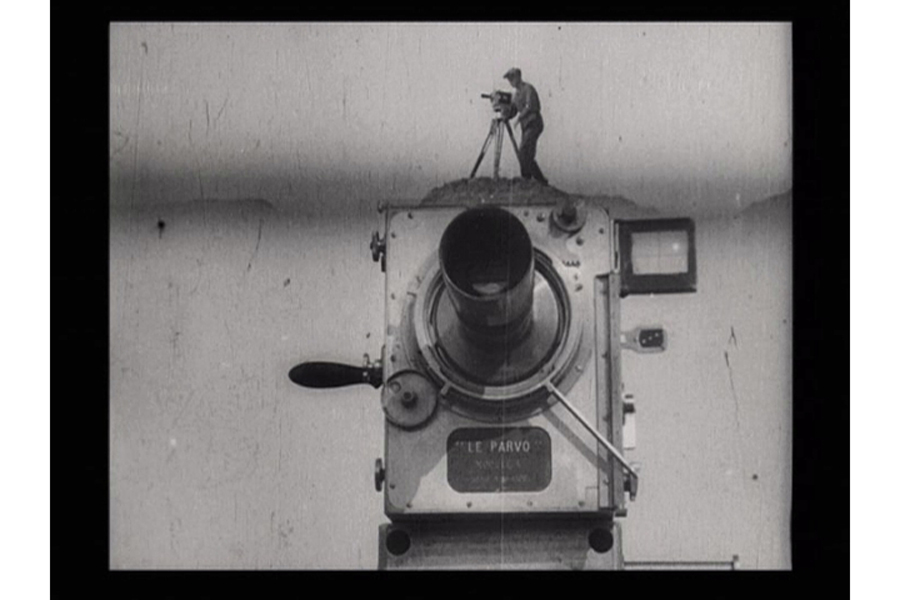

In 1927, after a conflict with “Sovkino” — the state joint-stock company that held a monopoly on film distribution in Soviet Russia — and accusations of formalism, Vertov moved from Moscow to Odesa. He completed Man with a Movie Camera at the Odesa Film Studio in 1929. This scriptless film-manifesto depicts a day in the life of a big city across six different episodes. For the filming, Vertov used experimental techniques such as animation, fast and slow motion, “hidden camera”, double exposure, and archival footage. Man with a Movie Camera‘ set standards in documentary filmmaking, editing, and cinematography and is still widely studied in film schools. Vertov shot his most outstanding films at the Odesa and Kyiv film studios, capturing Ukrainian realities of the period.

Formalism

An artistic concept in which the value of a work is determined by its form rather than its content. From the second half of the 1920s in the USSR, where socialist realism prevailed, any experimentation with form was interpreted as formalism — a characteristic of avant-garde art.

Frame from Man with a Movie Camera by Dzyga Vertov

Another of Vertov’s fundamental achievements in documentary filmmaking was the creation of the first Soviet sound film in 1930, Enthusiasm: (The Symphony of Donbas). This film captures the industrialization of the Donetsk region while also highlighting the struggle against religion, the elimination of illiteracy, and the nationalisation of enterprises. The soundtrack includes noise from industrial objects and the activities of people nearby. Charlie Chaplin, whose career was negatively affected by the advent of sound cinema, called Enthusiasm “one of the most moving symphonies I have ever heard”.

In the 1930s, the development of Ukrainian culture was curtailed, and mass repressions began. Studios in Ukraine started to be forced to operate under the “Soyuzkino” film association in Moscow.

Ukrainian documentarians during and after World War II

During World War II, the USSR formed camera crews to document the main events at the front line and quickly relay them to newsreels. Over 300 documentarians joined the Soviet military. In addition to official reports on battles, Soviet film periodicals showcased combat and civilian life, the work of the home front, and the reconstruction of regions liberated from the Nazis. They also created themed issues dedicated to specific events or individuals, including partisan groups.

In 1942, to mark the anniversary of the so-called Great Patriotic War (a propagandistic term for the German-Soviet war — ed.), Ukrainian documentarian Mykhailo Slutskyi filmed One Day of War, involving 160 cameramen along the entire front line. The assignment for the film outlined specific scenes that needed to be captured: combat operations of various scales and involving different types of weapons, river crossings under bombardment, German aircraft flying in anti-aircraft fire zones, destroyed enemy equipment, and the process of bombing it. This film became more of a propagandistic interpretation of reality rather than an example of objective documentary filmmaking.

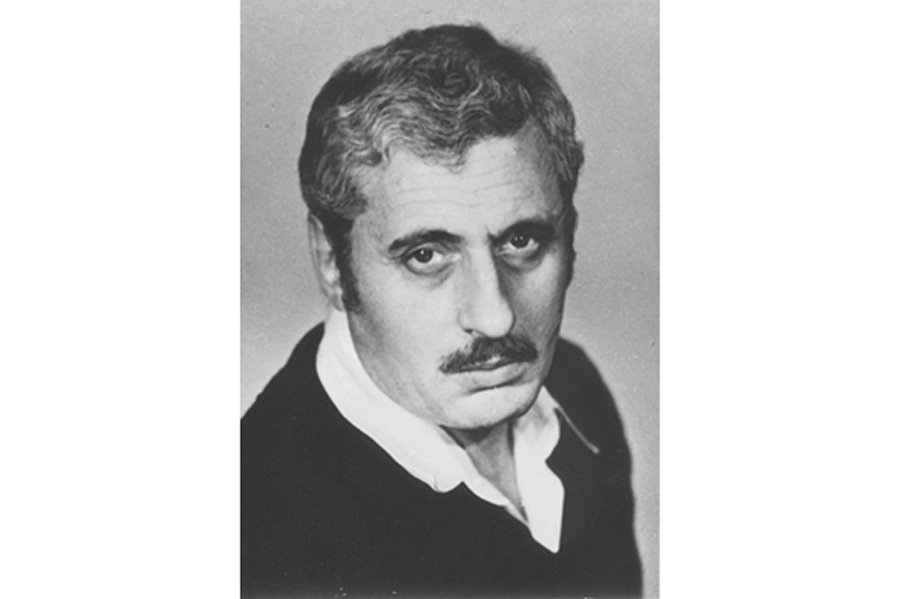

Mykhailo Slutskyi. Source: propagandist media of the Russian Federation.

The most monumental documentary films depicting military actions on Ukrainian territory were overseen by famous Ukrainian director and writer Oleksandr Dovzhenko. By 1939, his portfolio included silent films (Zvenyhora, Arsenal, and Earth) and sound films (Ivan and Aerohrad). With his wife and assistant Yuliia Solntseva, Dovzhenko received a government assignment to film the Red Army’s “liberation” campaign in western Ukrainian lands that had been part of Poland. This led to the creation of the documentary film Liberation, which presented the Soviet occupation of western regions of Ukraine in a favourable light for the USSR. The film depicted portraits of hungry and impoverished children to support the thesis of cultural and economic oppression by Poland. Dovzhenko contrasted daily life in Soviet Ukrainian cities with the region under Poland, exploring the role of individuals in wartime and reflecting the character of the entire nation through the personalities of his characters. Influenced by Dovzhenko’s filmmaking, other directors subsequently created propaganda films such as Soviet Lviv, Pearl of the Carpathians (1940), and Along the Soviet Danube (1941).

Oleksandr Dovzhenko. Source: Ukrinform (Укрінформ).

The documentation of the “reunification of brotherly Ukrainian and Belarusian peoples into one state” lasted for two months. The premiere of Liberation took place in 1940, but it was later withdrawn from circulation. This was most likely done to avoid reminding the population of the inconvenient truth about the Soviet Union’s collaboration with Germany to divide Poland according to the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact. A similar fate befell the film Bukovyna, a Ukrainian Land, which Dovzhenko co-created with Solntseva in her directorial debut. The plot tells how the people of Ukrainian Bessarabia and Northern Bukovyna began to experience a “better life” after the arrival of the Soviet army. The film serves as an example of Soviet documentary propaganda that manipulated collective consciousness and created a strictly positive image of the Soviet army and political leadership.

The pinnacle of Dovzhenko’s documentary-propaganda activity came with two films:

Ukraine in Flames (1943) and Victory on Right Bank Ukraine (1944). While working on the former, Dovzhenko was also completing the screenplay for the cinema novel “Ukraine on Fire, which was later criticised by Stalin for its “anti-Leninism, defeatism, revisionism of national policy, and encouragement of Ukrainian instead of Soviet patriotism”.

Frame from the film Ukraine in Flames by Oleksandr Dovzhenko.

For Ukraine in Flames, also created in collaboration with Solntseva, Dovzhenko served as artistic director and narrator. The film was edited from archival footage taken by 24 Soviet operators and video chronicles captured from Germans. Upon release, it was translated into 26 languages. Ironically, the English title of the film (Ukraine in Flames) serves as a bitter reminder of the war’s effects on Ukraine. The film largely avoids glorifying the achievements of the Soviet state, focusing instead on the suffering of the Ukrainian people during the war. It is a sound film enriched with Dovzhenko’s reflections and lyrical digressions.

Frame from the film Ukraine in Flames by Oleksandr Dovzhenko.

In Victory on Right Bank Ukraine, the narrative focuses primarily on portraying the USSR as the saviour of the Ukrainian people. Before starting work on this film, Dovzhenko collaborated with camera operators who had fought in partisan units. Based on their accounts, he produced Compilation of Stories in 1943 about the partisan movement in Ukraine. Dovzhenko was dedicated to preserving the historical memory of Ukraine’s involvement in the war and advocated for the establishment of a museum commemorating it.

From 1943 to 1953, there was a sharp decline in the number of films produced in the Soviet Union. This was due to the post-war economic crisis, the repression of artists, and the “fight against cosmopolitanism”.

Ukrainian educational films in the 1950s and 1960s

Despite reduced pressure from the authorities on cultural figures and the deterioration of Stalin’s personality cult, documentary filmmaking during the “Khrushchev Thaw” period still suffered from censorship, with certain films withdrawn from circulation.

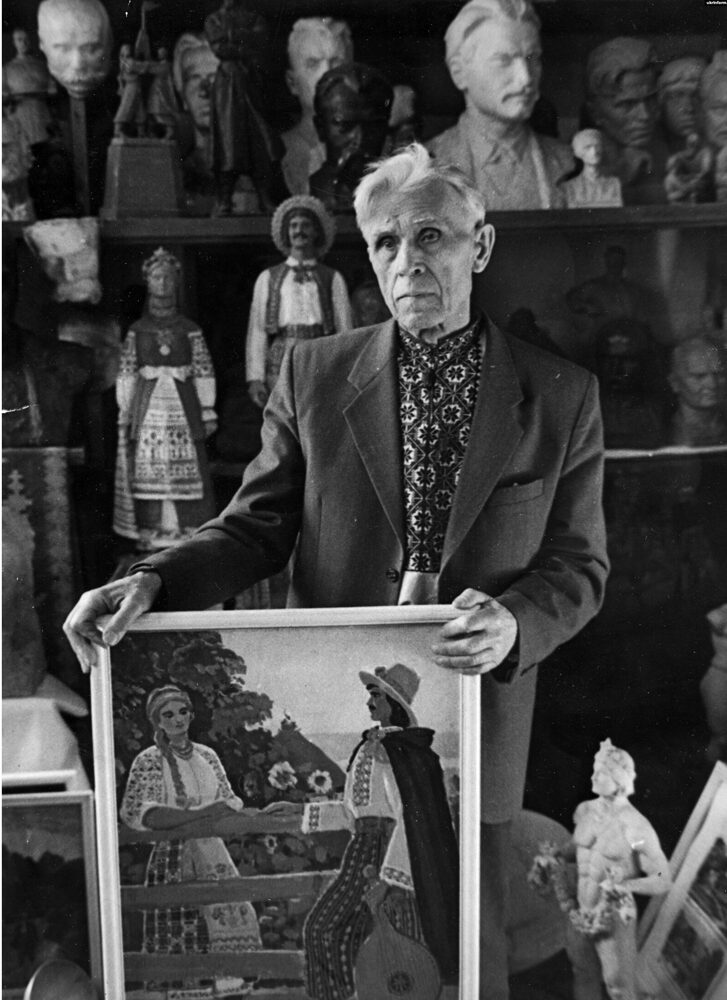

Ivan Honchar in his studio. Source: Ukrinform (Укрінформ).

Declaration of Love (1966) by Rolan Serhiienko portrays life in the Soviet Union through a woman’s perspective. The director was accused of distorting reality, and the film was shelved. Due to “political shortsightedness and the use of nationalist motives”, Sonata for a Painter (1966) by Viktor Shkurin was also banned. This film depicted the life of Ivan Honchar, a collector of Ukrainian antiquities who turned his Kyiv apartment into a unique museum.

The creation of mini-documentaries was an important step in the development of documentary cinema during the Soviet era. These documentary features chronicled the construction and launch of large industrial enterprises and energy facilities, the development of villages, and urbanisation. These recordings were put together to make educational and enlightening newsreels that were later broadcast on television.

A significant event in the world of documentary cinema during this period was the film Kermanychi‘ by Ihor Hrabovskyi, created in 1965 in collaboration with cinematographer Yurii Tkachenko. It tells the story of “bokorashes”, woodcutters in the Ukrainian Carpathians who would float lumber from mountain peaks down to valleys using the Cheremosh mountain river. Kermanychi received awards at prestigious international documentary film festivals in London, Leipzig, Oberhausen, and New York and became a valuable testament to a profession that was no longer passed down to the next generations by the early 1970s.

Ukrainian documentary filmmaking of the 1970s and 1980s

The rapid development of science significantly expanded the thematic scope and the number of films produced by the “Kyivnaukfilm” studio, which released scientific, educational, animated, and documentary films. Documentary filmmaker Felix Sobolev created a series of films showcasing various experiments, including The Language of Animals (1967),Seven Steps to the Horizon (1968), Do Animals Think? (1969), and Me and Others (1971).

Felix Sobolev. Source: Wikipedia

The poetics of Ukrainian documentary cinema were developed by director Oleksandr Koval. Seeking to change the image of cinema as a tool of propaganda or moral instruction, he began to capture generational memories by filming individual people’s lives. Malanka’s Wedding (1979) is a psychological portrait of a woman from the World War II generation. Oh Dear, These Guests Have Come To Me (1989), directed by Pavlo Fareniuk with Koval as cinematographer, tells the story of a witness to the Holodomor of 1932-1933.

Frame from the film Discover Yourself by Oleksandr Koval

Due to the policy of glasnost, which allowed information to be publicly broadcast without ideological pressure, documentary journalism became more active. Ukrainian filmmakers returned to reflecting on traumatic periods caused by Soviet occupation. For instance, they created documentaries dedicated to the artificial famine of 1932-1933, including 33rd, Eyewitness Testimony (1989) by Mykola Laktionov-Stezenko and Under the Sign of Famine (1990) by Kostiantyn Krainii.

In 1986, the Chornobyl disaster shattered the population’s remaining trust in the government. A group of documentary filmmakers led by Volodymyr Shevchenko arrived at the power plant 18 days after the explosion, on May 14, 1986, and spent nearly 100 days there filming in the most dangerous zones. Censors cut some scenes from the film Chornobyl: Chronicle of Difficult Weeks, but it still aired. The film not only covers the causes of the accident but also its preconditions, including the involvement of Soviet authorities.

Chornobyl: Chronicle of Difficult Weeks was one of the first documentaries to systematically record the aftermath of the explosion. It covers the construction of the shelter structure, or “sarcophagus”, over the power plant; the pumping of liquid nitrogen into the burning reactor; and the evacuation of people from contaminated areas. A month after the premiere, Shevchenko died from lung cancer caused by radiation exposure. In his diary, he wrote: “If someone tells me that if I hadn’t gone in, I would still have my lungs, I would immediately respond: I’d rather be without lungs than, like some, without honour.”

Frame from the film Chornobyl: Chronicle of Difficult Weeks by Volodymyr Shevchenko.

Gradually, the “Critical School of Ukrainian Documentary”’ (1987–1995) was formed, including directors Serhii Bukovskyi, Izrail Holdshtein, and Heorhii Shkliarevskyi. They expressed views on the inefficiency of the Soviet state system, social injustice, and mass democratic movements. A breakthrough for the school was Serhii Bukovskyi’s debut film Tomorrow Is a Holiday’ (1987), which depicted the daily lives of workers at a typical Soviet poultry farm. It shows life in dormitories; a lack of basic amenities and comfort; and fatigue from monotonous state holidays, parades, and other rituals. The director filmed on state commission but also used the image of the poultry farm as a metaphor for the entire Soviet Union. Bukovskyi noted that this subtext emerged only after the editing process.

Ukrainian documentary cinema in the first decade of independence

In the crisis-ridden 1990s, documentary cinema became a way to search for identity, rediscover history, and grasp new social values. The difficult situation of the film industry during this period was linked to a lack of state support and the absence of legislation for private film production. Despite these challenges, high-quality works were still produced. In 1993, the Unknown Ukraine documentary series was created, involving 68 directors and 50 cinematographers. Each episode recounted a specific historical period, from ancient times to the achievement of independence.

In the early 2000s, the influence of television grew as it began commissioning and broadcasting documentary films, leading to a proliferation of documentary series. In 2003, Serhii Bukovskyi created the War. The Ukrainian Account documentary series about World War II events in Ukraine. Later, in 2006, he directed the film Spell Your Name, where he interviews people who survived the Holocaust in 1941-1942. American director Steven Spielberg served as executive producer.

In parallel, the younger generation of documentarians was honing their skills, eventually taking leading positions in Ukrainian cinematography. In his debut documentary exploration titled Songs of the Forgotten (2000), Volodymyr Tykhyi delves into the issue of identity among Ukrainians resettled to the Far East between 1882 and 1914. The only thing connecting these people to their ancestors is Ukrainian songs. Similar themes of exploring people’s roots appear in Valentyn Vasianovych’s first short documentary, Old People (2001). Films dedicated to the events of the Orange Revolution included Oles Sanin’s The Seventh Day and Serhii Masloboishchykov’s People from Maidan. Nevseremos! (2005).

In 2005, Ukraine received its first Palme d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival for the short film Wayfarers by Ihor Strembitskyi. The film, which was Strembitskyi’s graduation project at the Karpenko-Karyi Kyiv National University of Theatre, Cinema and Television, depicts the daily life of a neuropsychiatric hospital near Kyiv. Despite the film’s success, it did not secure a prosperous career for the director. Amidst the industry crisis, Strembitskyi, like many of his colleagues, turned to work in television.

Among the most resonant projects in Ukrainian television documentaries at that time were two investigative series by the 1+1 TV channel: Uniform of Brutality, which exposed abuses by law enforcement agencies, and White Robe Negligence, which highlighted corruption within healthcare institutions. These documentaries led to official investigations and the dismissal of local government officials.

Screenshot of the cover of one of the episodes from the Uniform of Brutality series.

The early 2010s ushered documentary cinema into a lethargic state: independent documentary projects remained in prolonged development, while television documentaries often received insufficient funding and airtime. For the 20th anniversary of Ukraine’s independence, Serhiy Bukovskyi created the documentary TV film Ukraine. The Starting Point, which closely traces the events of three years in Ukrainian history, namely 1989, 1990, and 1991, when Ukraine finally won its independence.

Documentary filmmaking in Ukraine after the Maidan Revolution

Ukrainian documentary filmmaking on the Maidan became a form of civic activism. This genre was created by artists who filmed the events of the revolution daily and shared them on social networks. The “Babylon’13” Ukrainian documentary filmmakers’ association was formed at the end of November 2013. In their manifesto, they proclaim: “Our main task is to show the birth and first decisive steps of civil society because the latest events in the country primarily indicate the formation of a new civic consciousness among Ukrainians, centred on self-organisation, solidarity, and the defence of natural human rights.”

According to the documentarians, the generation of Ukrainians shaped during the period of independence was the driving force behind the formation of a new civil society. They saw documentary filmmaking as a way to spread ideas related to important social reforms and create a community of like-minded individuals.

From December 2013 to January 2014, members of Babylon’13 created dozens of short documentary videos, including The first moments of the assault on Kyiv city hall, the Battle on Hrushevskoho Street series, Brick by brick, and more. 2014 also saw the release of the first comprehensive artistic interpretation of the events, titled Euromaidan: Rough Cut. This work was based on materials from a whole group of documentarians: Volodymyr Tykhyi, Andrii Lytvynenko, Kateryna Hornostai, Roman Bondarchuk, Yuliia Hontaruk, Andriei Kisielov, Roman Liubyi, Oleksandr Techynskyi, Oleksii Solodunov, and Dmytro Stoikov.

The confrontation with Russia and the awakening of national consciousness created a demand for documentary interpretation. Films about the Revolution of Dignity emerged, such as Winter on Fire’ (2015) by Yevhen Afinieievskyi and the documentary series Winter, that has changed us by Babylon’13. There were also documentaries about the occupation of Crimea, including Whose Crimea? The Holiday of Annexation by Kseniia Marchenko and Crimea as It Was by Kostiantyn Kliatskin (2016).

During the initial stages of the Russo-Ukrainian War, documentarian Leonid Kanter filmed the critical documentary War at Our Own Expense. This work highlights the inadequate provisions for soldiers of the National Guard of Ukraine (at the time, the director was fighting in its ranks). Later, Kanter made the film The Ukrainians (2015) about the members of the Ukrainian Volunteer Corps and the defenders of Donetsk Airport. The filming of the defence lasted two weeks, and the film’s final phrase became famous: “People endured, it’s the concrete that didn’t.” In 2018, Kanter and his frequent co-director Ivan Yasniy created a documentary portrait of Vasyl Slipak in their film Myth. Slipak was a world-renowned opera singer and soloist of the Paris National Opera who left the grand stage and gave his life defending Ukraine.

Frame from the film Myth

As a result of prolonged military actions, the themes of documentary cinema have expanded. Films about volunteering in the ATO zone have emerged (Brothers in Arms‘ by Serhii Lysenko), as have sketches about life in the frontline areas (The Earth Is Blue as an Orange by Iryna Tsilyk, Terykony by Taras Tomenko, The Distant Barking of Dogs and A House Made of Splinters by Simon Lereng Wilmont) and stories about soldiers during and after their service (Company of Steel by Yuliia Hontaruk, War Note by Roman Liubyi).

Antiterrorist Operation (ATO)

A series of measures by Ukrainian security forces aimed at countering the activities of illegal Russian and pro-Russian armed groups in the war in eastern Ukraine. It started in 2014 and was transformed into the Joint Forces Operation (JFO) in 2018.Ukrainian documentary filmmaking today

More new thematic directions in Ukrainian documentary cinema have begun to emerge since the start of the full-scale invasion. In the Fortress Mariupol documentary series, director and co-founder of the Babylon’13 collective Yuliia Hontaruk focuses on the return of military personnel to civilian life, the rehabilitation of fighters from the Azov Brigade after captivity, and the consequences of post-traumatic stress disorder.

Frame from a film in the Fortress Mariupol documentary series.

Co-founder of Babylon’13, director, and screenwriter Volodymyr Tykhyi crafted a duology where key events unfold over a single day in different regions of Ukraine with different protagonists. The two films are titled One Day in Ukraine‘ and Ukrainian Independence. As It Is’. Roman Liubyi experiments with form in his hybrid documentary Iron Butterflies, combining elements of live action and documentary to reflect on the experience of war. Kornii Hrytsiuk’s work explores and decolonises the history of eastern Ukraine, such as in the film Eurodonbas.

Poster for Kornii Hrytsiuk’s film Eurodonbas. Source: State Cinema Agency (Держкіно).

Documentaries depict the war in its various manifestations, from personal reflections to the experiences of entire cities, as seen in Mstyslav Chernov’s film 20 Days in Mariupol. Directors show the consequences of war through portraits of civilian victims in films such as Anastasiia Tykhа’s Our Robo Family, Dmytro Hreshko’s King Lear: How We Looked for Love During the War, and Alisa Kovalenko’s We Will Not Fade Away. Many directors also aim to connect the experiences of this new stage of the war with previous ones, such as the Antiterrorist Operation (ATO) or earlier Russian or Soviet hybrid operations.

These stories are often based on the artists’ personal experiences. For example, in A Picture To Remember, Olga Chernykh explores the power of memory and how it helps us cope with reality. Olga grew up in Donetsk in the 1990s, then moved with her parents to Kyiv. Her grandmother remained in Donetsk, and after the initial Russian occupation, the full-scale invasion only intensified Chernykh’s sense of distance between herself, her grandmother, and home in general. However, it was during this time that the director was able to create a new form of film, a project she began working on in 2019.

A Picture To Remember depicts how three generations of women perceive war. The film is based on video conversations between Olga, her mother, and her grandmother, as well as on photos and videos from her family archive. In 2023, it opened the International Documentary Film Festival Amsterdam (IDFA), the world’s leading documentary film festival.

Frame from the film A Picture To Remember.

Olga believes that changes in the industry should come primarily from Derzhkino and the Ministry of Culture and Information Policy. In addition to greater popularisation of the genre, financial support should also be prioritised. Olga says that documentary filmmaking in Ukraine is currently a non-profit endeavour, mostly relying on state funding. However, she finds additional sources of support and continues to film.

“In reality, when you make films (both documentary and live action), it’s a form of therapy for yourself. On the one hand, it’s very traumatic because if you work with some kind of trauma, you re-traumatize yourself every time […]. But there is also a healing aspect. […] I love documentary filmmaking because of this empathy and love that is often present there. But I also don’t do enough of it, and it’s often lacking in our cinema. It doesn’t depend on countries, it depends on directors, on how they do it.”

Frame from the film A Picture To Remember.

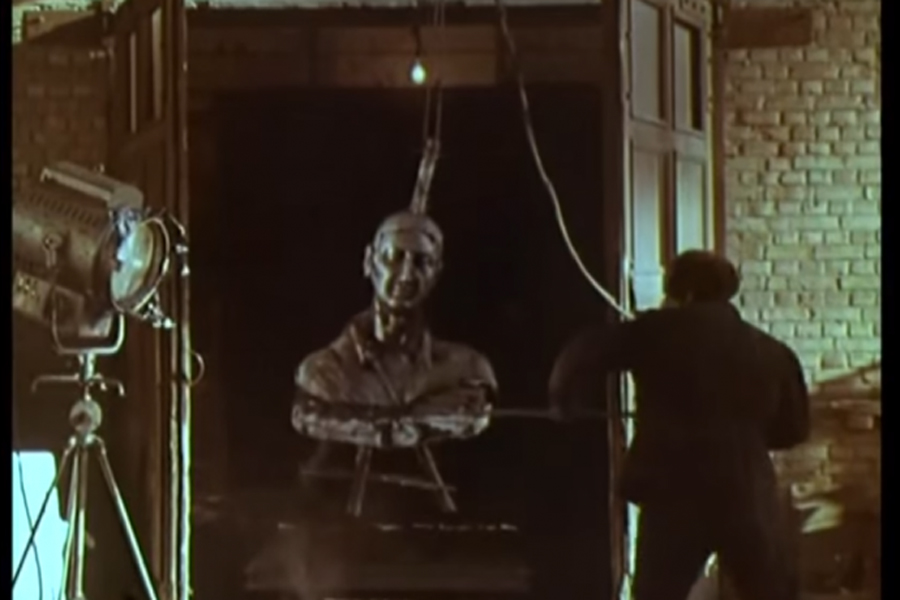

A lack of funding often pushes contemporary Ukrainian directors to work with archives. This can be cheaper than documenting live events, and it helps uncover more about national history and reinterpret past experiences. Director Taras Spivak conducted such research to create Under the Sign of the Anchor. In this film, he aimed to construct an alternative version of history where the Cold War did not end. Spivak satirises the Soviet army and military-industrial complex (or “war machine”) and what remains of it while simultaneously illustrating how frightening and absurd it can be. Under the Sign of the Anchor is based on archival materials from the times of the USSR’s collapse and the early years of Ukraine’s independence, focusing on the Kyiv Higher Military-Political School and the “Kyiv” Soviet aircraft carrier.

Cold War (1947–1991)

A geopolitical, economic, and ideological confrontation between the Soviet Union on one side and the United States and Western European countries on the other. There were no direct military clashes between the blocs.

Frame from the film Under the Sign of the Anchor.

As a director, Taras says that he would like to see more similar films in Ukraine. Working with archives has many advantages and makes documentary filmmaking more accessible. This is especially important in times of war, when searching for life’s meanings is still necessary, and major resources are directed towards supporting the army.

“Archives are such a quick entry into this (documentary filmmaking — ed.). […] In this sense, archival and montage filmmaking in general has a very convenient economy as a method of organisation. It’s often inexpensive […] because it can be done without the efforts of dozens of people, unlike live action filmmaking, which requires hundreds of people. And it can be very impressive, very effective in what it does.”

Taras also believes that it’s not just about having more interest in archives, but also caring for them responsibly. While archival filmmaking can be inexpensive, preserving and restoring film quality can have significant costs. Taras and his friends found the material for Under the Sign of the Anchor in the attic of the National Film Archive of Ukraine (formerly known as Kyivnaukfilm/Київнаукфільм). During the summer of 2021, the director catalogued 12,000 film reels that were stored in inadequate conditions.

Frame from the film Under the Sign of the Anchor

Another reason for Taras’s decision to work with archives is that he doesn’t want to speculate on the theme of the Russo-Ukrainian war. Ukrainian society cannot yet distance itself from this reality, so the ways in which it is documented naturally evolve. For instance, Taras notices that journalists are increasingly using wide shots of mutilated bodies and other consequences of the war instead of close-ups.

“I understand those documentary filmmakers very well because I’ve also seen the documentation of horrors. And I have only one thought about them. If this documentation aims at some kind of fight for justice, if they serve as legal evidence, then it makes sense indeed. But if it’s about personal ambitions or artistic intentions and so on, I think it’s somewhat inappropriate.”

Taras says it remains challenging to abstract oneself away from realities in order to live and comprehend them. In his view, working with archives helps us reassess the biases and perceptions of a specific historical period that we continue to carry with us:

“In the future, after dismantling the structure currently known as the ‘Russian Federation’, we will have both the right and the privilege to claim these archives. For our history, for the history of our ancestors.”

Frame from the film Under the Sign of the Anchor

Despite limited funding and other challenges, Ukrainian documentary films are increasingly making their way to international film festivals. These films speak not only to Ukrainians, who share a common trauma, but also engage Western audiences who may not be as familiar with the realities of armed aggression. In March 2024, Ukrainian film director and war journalist Mstyslav Chernov and his team received Ukraine’s first Oscar in the Best Documentary category for 20 Days in Mariupol. This film depicts Russia’s siege of the city in February-March 2022.

Such victories provide a platform to counter Russian propaganda, showing the world that Russia remains imperialistic by nature and continues to perpetrate genocide. Director Oksana Karpovych works within this context, using intercepted conversations between occupiers and their families in her film Intercepted. The film is accompanied by footage from de-occupied Ukrainian cities and villages. It received two awards at the Berlin Film Festival: the Special Prize of the Ecumenical Jury in the Forum section (for artistic quality and addressing religious, social, and humanitarian issues) and a Special Mention from the Amnesty International jury.

Frame from the film Intercepted

During the premiere, international audience members often questioned the authenticity of the recordings. Some people claimed the director cooperated with the Ukrainian special services and intentionally distorted reality. However, Oksana Karpovych maintains that she approached the material primarily as a film director and aimed to show this Ukrainian reality to foreigners. She emphasised that some participants in the recordings were identified.

“My position as a film director is transparent,” says Oksana. “I acknowledge (and declare in the film) the nature of these recordings. I also understand that their online publication for a wide audience was part of Ukraine’s information war. […] Everything we hear in these recordings corresponds to the reality we live in. In Ukraine, we don’t need intercepted communications to know that the Russian army kills civilians, rapes women and children, loots, and uses prohibited weapons – we already have plenty of documented testimonies and evidence of this.”

Frame from the film Intercepted

Despite the audience’s prejudice, Oksana Karpovych observed that her film did influence the audience, prompting them to view Russia from a new perspective distinct from its cultural propaganda or diplomatic ties.

“Intercepted raises a series of questions that perhaps the German audience hadn’t considered before,” she says. “It addresses the awareness of ordinary Russian citizens, the overall standard and quality of life in Russia, the hierarchy of their army, the culture of looting, even the nature of the Russian language and its relevance to what is happening. Making people in the West talk about Russia in the context of violence and imperialism rather than just ‘ballet’ is an achievement for me.”

The different stages of Russian aggression are a significant theme in Ukrainian documentary filmmaking, but they aren’t the only one. Such films can also serve as acts of activism and portraits of genius (Infinity According to Florian‘ by Oleksii Radynskyi), requiems to the 1960s through the fate of a couple (Ivan and Marta by Serhii Bukovsky), or quests to find one’s own place in the world (Elevation by Maksym Rudenko). The premiere of the latter took place at the Docudays UA festival.

Maksym Rudenko began work on his film long before the full-scale invasion. He met the main character, Vasyl, during the filming of his previous feature-length film, A Portrait on the Background of Mountains (2019). Vasyl is a ski jumping coach who found his life’s purpose. Maksym didn’t want this man’s story to be lost, so he decided to dedicate a separate film to it.

“This is not just a story about ski jumping; it’s about how important it is to find your place in the world and pursue your calling. The main character embodies this message 100%. He knows he’s doing what he’s meant to do. It’s such a unique case that I tell through this character, about the power of choice in life.”

Frame from the film A Portrait on the Background of Mountains

The director and his team went on expeditions to the Carpathian Mountains over five years. To capture the life of the coach and his trainees realistically, Maksym and Vasyl lived in the same room, attended training sessions together, and communicated constantly throughout the day. The protagonist was open to the camera and almost ignored it. Due to his close bond with the coach and his desire to depict as much as possible, editing the film was challenging, admits the director. Additionally, each frame involved a lot of physical work — equipment could sometimes be carried up to 25 kilometres in the mountains. In such cases, according to Maksym, editing directors who are not involved in the filming can help better identify the strengths and weaknesses of the material. The whole team plays a crucial role in documentary filmmaking:

“Everything depends on the team in documentary filmmaking. Sometimes, it may be a very simple shoot, just some interesting idea, but the team can develop these ideas to such a perfect state that it becomes a great film. Because filmmaking is always about both the idea and how it’s executed.”

Frame from the film A Portrait on the Background of Mountains

Maksym has noticed that the global film industry has grown tired of war. Initially, international festivals rejected his film Elevation due to its peaceful subject matter, but now the situation has changed — the Western film community wants to see pleasant images. For himself, the director has decided not to film about the war right now (the events are too vivid), but to go and fight. He calls on his colleagues to join the ranks of Ukrainian defenders.

“Now is not the time for art, but the time for war, at least for men,” Maksym says. “I don’t understand men who are filming something now. Those who know the military situation, they know that our country is one step away from [the threat of ceasing] its existence. If everyone here doesn’t come together, there won’t be any country left.”

Maksym doesn’t know if he will continue his career as a documentarian, but he wants to show Elevation to audiences. While watching the film, it is difficult to clearly identify if it stemmed from a specific initial idea. As often happens with documentary films, the meanings are mostly shaped during editing. In this case, during filming, the director was motivated not by a final idea for his own work, but by his impressions of another film by a Lithuanian director about a woman living in the mountains.

“[…] Even when you think there’s nothing around to film, because the mountains are quite monotonous, you still understand that you are now shooting through a small hole with the camera, and then it will be on the big screen and there will be sound. I can’t say that I really wanted to know so much about sports, about this character. It’s research. You don’t know what will happen to him. It’s basically reconnaissance by combat. You don’t know if you’ll finish the film.”

Frame from the film A Portrait on the Background of Mountains

The future of Ukrainian documentary cinema is hard to predict, but it remains crucial for this art form to capture reality as it is here and now. Contemporary documentary cinema can speak about events that happened yesterday or a hundred years ago, explore personal or national themes, provoke discussions, and drive social change. Throughout its existence, the work of documentarians has been challenging yet essential, as it preserves reality — a particularly valuable task when many Ukrainian archives of past centuries are now in Russia.

Today, film crews continue this work under the conditions of full-scale war, often risking their lives. Therefore, the best support for them and for Ukrainian cinema in general is viewership.