To focus on critical infrastructure or restore all damaged objects is a challenging question for Ukraine, which is even more pressing for the border settlements in the country’s east and north. The proximity to the Russian border does have an impact, but it should not be the determining factor in this issue, believe Okhtyrka residents, who keep developing urban vision of the city and preserving its historic landmarks despite the wartime threats.

I n the previous materials of the Restoration project, we covered how Ukrainians are rebuilding Kharkiv, Chernihiv, Mykolaiv, and settlements north of Kyiv after Russian shelling. This time, we will focus on another city recovering from the consequences of the full-scale invasion — Okhtyrka, located in Slobozhanshchyna.

Once, Okhyrka was a village inhabited by Cossacks. As a legacy from this period, residents still refer to the city districts using the traditional division into sotnias, with ten sotnias in total. Later, Okhtyrka developed through crafts and trade, which left behind buildings in the historic downtown area. The new chapter in the region’s history is closely linked to oil extraction; the Okhtyrka oil district accounts for 50% of Ukraine’s total oil production, with the highest level of oil extraction reached in 1990. Additionally, Okhtyrka is notable as the birthplace of Ivan Bahrianyi, the prominent 20th-century Ukrainian writer whose works remain popular with contemporary youth.

Okhtyrka is located on the border of Poltavshchyna and Slobozhanshchyna, equidistant from Kharkiv, Sumy, and Poltava. The town stood in the way of the Russian army during the full-scale offensive in February 2022. Despite more than a month of intense fighting, the enemy failed to occupy Okhtyrka, which nonetheless sustained significant damage, with many lives lost due to the shelling.

Cossacks

a martial stratum that occupied Ukraine’s southern steppe frontier from the mid-16th to the late 18th centuries. Initially self-organised for defence, it evolved into a democratic society, renowned for its self-governance and crucial contributions to Ukrainian identity.Sotnia

“Hundred” in Ukrainian; a military unit comprising 100 people and an ancient Ukrainian administrative-territorial division based on it.

The Okhtyrka’s location, roughly fifty kilometres from the Russian border, certainly makes an impact on the pace of its restoration. Yet, local self-government and concerned residents readily share what has already been accomplished so far and what plans lie ahead.

How the City Authorities Envision the Restoration

Pavlo Kuzmenko, the mayor of Okhtyrka, is trained as a doctor. Before taking office, he served as the head of the traumatological department at the district hospital. Despite the potential risks, he and his team remained in the city during the full-scale invasion, even though it posed a severe threat to him as a local government representative if Russian troops had occupied Okhtyrka.

“When I saw on the cameras that enemy vehicles were driving over our flowerbeds, everything became clear. As a local government body and as patriots of our country, we realised there were two options: either defend ourselves or be killed,” the city head recalls.

Pavlo stresses that despite suffering significant destruction, Okhtyrka was not occupied. Locals witnessed the resistance of the Ukrainian military as the enemy attempted to raze the city to the ground.

“Our city was devastated, ravaged as an act of revenge for not letting the enemy through,” he says.

The first shelling started on 25 February, 2022: The Russian forces used cluster munitions against a kindergarten where many civilians were taking shelter. The next day, the shelling intensified.

“Three thermobaric bombs were dropped on our city. The city shook, and it seemed like there was no corner where anyone felt safe.”

The large number of wounded and the urgent need for medical assistance prompted Pavlo to take on surgical duties in those early days of the invasion.

“Having worked as a doctor for 20 years, I have saved human lives and health that were lost due to plane crashes, household injuries, and other incidents, but here they came to kill us.”

On 3 March, occupiers destroyed the Okhtyrka Thermal Power Plant, leaving the city without heating and electricity. Pavlo views this as an attempt to force submission. Despite the ongoing fighting near the city, everyone willing to evacuate had the opportunity to do so. Pavlo notes that the city authorities deliberately abstained from setting up a green corridor as it would have exposed the evacuation routes to the enemy, who could then target the buses carrying civilians.

Local government representatives volunteered to split the duties, such as managing evacuation, supporting the elderly, and providing food for the military, which allowed them to navigate this challenging situation.

According to local authorities estimates, up to 26,000 people left the city by the end of March 2022. However, as of 2024, most of them have returned. Pavlo also stresses that the counts are conducted using unconventional methods.

“Since all children were studying online, you can’t know if they were in your community or not. However, when charitable organisations provided various treats, we distributed them personally. For example, a charitable foundation brought two trucks of candies. We handed them out to children and counted that we had more than 6,000 children. Out of 7,200 [registered] children, more than 6,000 are back in the city — that’s great. It means their parents have also returned, and their grandparents are here.”

Pavlo points out that he sees nothing wrong with people choosing not to return until the end of the all-out war. The danger has not passed, with ongoing shelling and the threat of another attempt to occupy the city.

After the defence forces drove the enemy out of Okhtyrka, Pavlo, during a meeting with the head of the military administration dedicated to reconstruction, called for focusing solely on critical infrastructure and civilian housing. Illustrating his point, he used a metaphor comparing the country to a large organism and cities to its organs and prioritised creating conditions for them to simply function — no more, no less.

“We are not spreading our efforts thin on rebuilding things we can live without today. Our task is to form thick granulation tissue, to separate ourselves from that overpowering infection, from the enemy, and only then to rebuild the entire organism.”

Granulation tissue

a medical term referring to the tissue that forms at the boundary between infected and healthy tissue in the body.

Pavlo believes that the state authorities should be more invested in rebuilding thermal power stations; instead, they limited their role to providing financial aid.

“For some reason, everyone thought that reconstruction meant simply providing funds; they voted, allocated 80 million [hryvnias] (roughly $2 million – ed.), and [expected] us to build.”

Pavlo believes that recovery efforts during wartime need to be more centralised, as they involve complex projects requiring thorough research, specialised expertise, and proper documentation.

“Dear friends, try playing democracy when, God forbid, one of your relatives or loved ones needs urgent surgery. You can vote on what kind of anaesthesia to use. First, gather those who need to vote — these will be parents, relatives, siblings, and children; then decide who will perform the surgery, and then everything else, and your loved one will quickly die. Someone needs to take responsibility at this time.”

Pavlo agrees that the city authorities should be proactive in the reconstruction efforts, but emphasises that some processes need to be adapted to the realities of war. For example, he believes that allowing the executive committee to make reconstruction decisions instead of the city council would expedite the efforts. The local budget allocated funds for restoring the damaged apartment building, along with one of the five boilers of the power plant. It turned out that this was sufficient for now.

“To start rebuilding a facility like the thermal power station, we needed to develop a heating scheme for the city. Since the station was built, some organisations that used its heat no longer exist, so restoring the Okhtyrka Thermal Power Plant to its full capacity was no longer necessary.”

In 2022, Okhtyrka’s local self-government created an electronic platform called EPKO (Electronic Platform for Communication – ed.) to manage donor assistance according to the requests of Okhtyrka residents. Its concept resembles the government initiative DREAM, which we featured in the piece on the restoration of Irpin. However, while DREAM involves community registration, EPKO functions as a register of individuals whose homes were destroyed or damaged due to the full-scale war, helping them to restore their accommodation through the mediation of the city authorities, funds, charitable organisations, and benefactors. Pavlo summarises that the overall restoration of Okhtyrka is funded through several sources: state funds for critical infrastructure, the local budget, and assistance from charities.

Many Okhtyrka residents participated in the eVidnovlennia state program. However, Pavlo points out that the local authorities immediately faced a shortage of personnel to inspect homes and assess the damage, which is essential to qualify for aid. Likewise, they had to adapt to frequent changes in the program as developers gradually updated it based on user feedback. Additionally, there were instances of misuse, in which recipients spent funds inappropriately or resold building materials. Nevertheless, the state puts efforts into enhancing accounting, reporting, and transparency to prevent such incidents from repeating.

eVidnovlennia

Ukrainian for eRestoration; a Ukrainian government program that provides financial aid for repairing and rebuilding housing affected by hostilities.

Pavlo is pleased that Okhtyrka has many active young people who plan to stay in the city and have initiated the Okhtyrka: Urban-Vision project dedicated to the city’s future development.

“These young people have travelled abroad and compared [Okhtyrka] to other European cities and Ukrainian cities. They have seen many [things that are] better than what we have. But they have also seen that our city is quite beautiful as well.”

Pavlo believes that the city’s future should be envisioned within the context of a united territorial community, which consists of Okhtyrka and the nearby settlements near the border with Russia. He believes that this approach will positively impact the reconstruction efforts.

“There should be one large Okhtyrka community extending to the border, a fortified community that can quickly make decisions and build whatever is needed, restore, and develop everything anew.”

The Story of Coming Back or There’s No Place Like Home

Before the full-scale invasion, Okhtyrka had a population of approximately 48,000 people. Many residents fled in the early days of the invasion when the Russians started shelling the city. As of summer 2024, the city population accounted for roughly 43,000 people, indicating that most residents had returned home. Many took advantage of the governmental eRecovery program, which provided financial assistance for repairing homes damaged by hostilities. One of the program’s beneficiaries is Tetiana Mikhel, who lives near the damaged power station – she left shortly after the Russians destroyed this critical infrastructure object.

“Everything here was destroyed. We fed a lot of dogs and cats. Neighbours left, and I was here alone. I left food for the dogs and cats. My children called and told me to leave. I went to Poltava and from Poltava to Odesa; I wanted to go home from Odesa, but I was put on a train and ended up in Germany.”

Tetiana stayed in Dresden for over a year but chose to return despite her home being damaged by the shelling: windows and doors were broken, and the roof was severely damaged. Initially, there was no gas, electricity, or water in her home due to the extent of the damage. Relatives helped to repair the roof, but it started leaking again after another shelling. Tetiana says that she returned because her dog was waiting for her at home and because, as she puts it, there’s no place like home.

“How can you abandon [your own] country? How can you abandon all this? Are you serious?”

Tetiana mentioned that in May 2023, representatives from the Administrative Services Center (a nationwide network of state facilities providing administrative services in Ukraine – ed.) and the police documented the damage to her home. When the eVidnovlennia program started, she applied for compensation. By the end of July, the government allocated 200,000 hryvnias, which covered most of the repairs, while charitable organisations helped cover the remaining expenses.

“Total strangers helped me,” she says.

Urban-Vision and Street Culture of the City

Pavlo Ihnatchenko is an activist, a member of the Street Culture Development Center non-profit, a promoter of cultural events, and a musician. In 2022, he was the one to launch the urban development plan Okhtyrka: Urban-Vision.

Pavlo believes that every city and town has unique potential and should emphasise its authenticity. After the defence forces pushed the enemy out of northern Ukraine and news of reconstructing settlements near Kyiv began spreading, he started thinking about how and when Okhtyrka would be restored.

“I remember looking at other cities that were discussing reconstruction while we were sitting idle. It seemed like we were the outpost – we met the enemy and fought them back; yet, nothing had been happening here since then.”

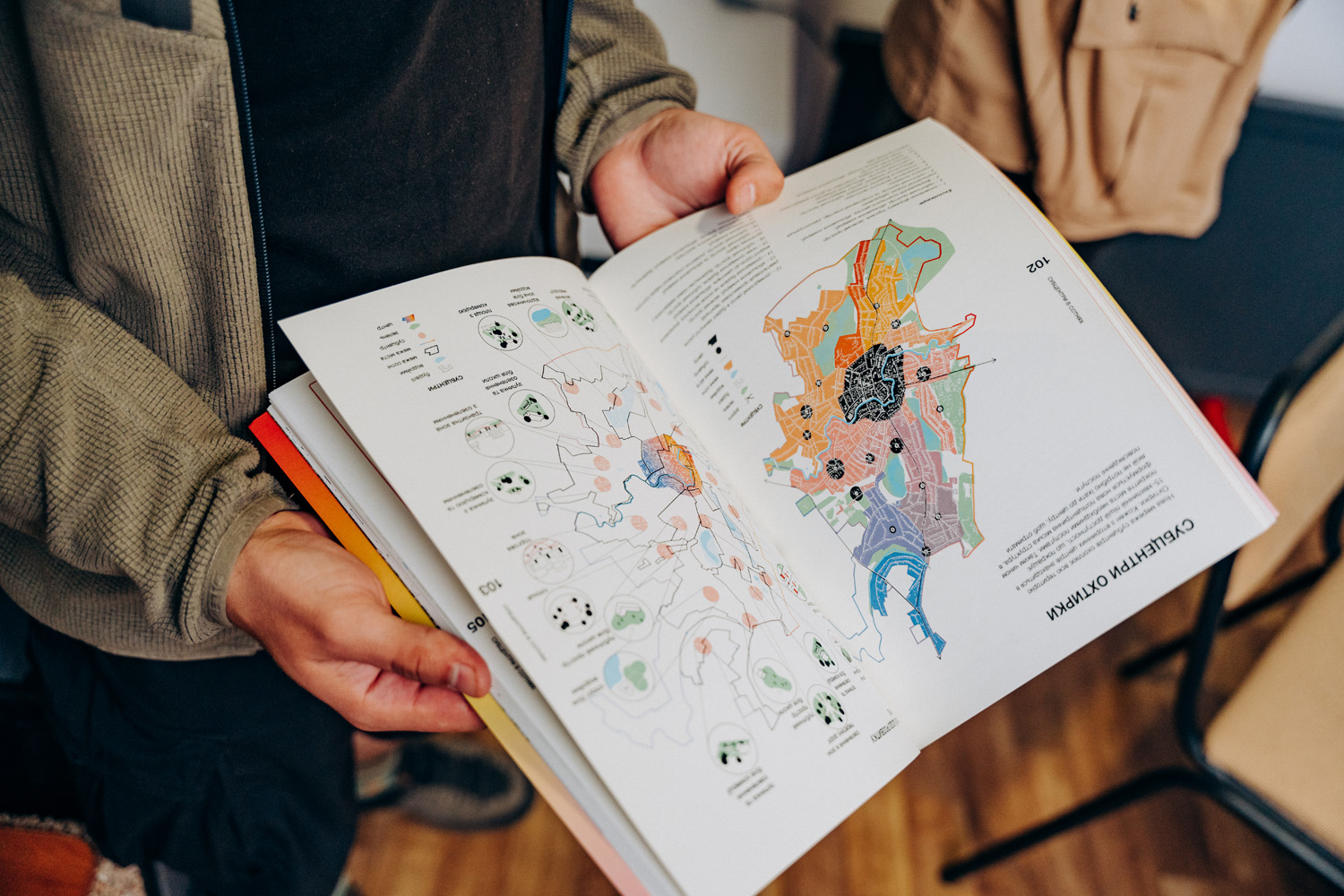

He reached out to his acquaintances, urban planners and architects from the Urban Reforms organisation, who were implementing similar projects in Kharkiv and Kyiv. They suggested working on an urban vision for the city — a kind of an informal guide that can assist professionals who develop the official master plan. This primarily involves identifying Okhtyrka’s strengths and weaknesses, allowing residents to voice their opinions, and identifying the pillars on which the future development should be based.

With the support of international partners, Urban Reforms provided a grant to Pavlo’s team, boosting the process. Despite the initial scepticism, the local authorities eventually supported the initiative.

“At first, they didn’t take it seriously, you know, it was like, ‘Well, let them do something, play around, so they bother us less.’ But then, we managed to explain to them how important this is for the city — not for them, not for us, but for the city and its future restoration.”

Pavlo calls the urban vision a project of shared vision, as it managed to engage experts, authorities, and locals. It employed various interactive approaches to ensure that everyone could express their opinions. For instance, people were given a map of Okhtyrka and asked to mark the places that needed improvement, such as building a bridge over the lake, adding a bike path, or installing a ramp.

“If we are talking about restoration and modern practices, then it is worth considering the community’s opinion. Nothing for Okhtyrka without Okhtyrka’s residents was the main principle of this vision.”

The vision also considered the interests of Okhtyrka’s numerous farmers and small businesses, which need comfortable working conditions. One of the most difficult issues for discussion was the future of the sites where people died due to Russian strikes. Another focus of the vision was the preservation and promotion of cultural heritage.

“In the modern world, promotion is one of the key components primarily for attracting tourism, and globally, for [boosting] investment and development. Because if no one knows about you, you don’t exist.”

Similarly, the project team focused on issues related to youth leisure. This topic is close to Pavlo’s heart, as in 2018, he initiated the creation of a skate park, which was completed in 2023. The focus on skateboarding came from its popularity in the city. Yet, Pavlo calls this space a universal place for developing street culture and facilitating youth communication, and, due to its multifunctionality, a kind of constructor.

“Building this, we thought: okay, there are ramps here, but we can also install a stage here, and it will become, so to speak, a dance floor. Now, there are tennis tables, but if we really want to, we can remove them, and it can serve as a lecture hall, a cinema, and so on.”

Pavlo acknowledges that the proximity to the border with the aggressor profoundly impacts city life. Yet, he stresses the importance of believing in a better future and continuing to make progress while considering the risks.

“Kharkiv residents will understand me: the most important thing for us right now is not to become a forgotten outpost, like somewhere out there, almost on the border with Mordor.”

Mordor

A fictional country from the world of Middle-earth in the works of English writer J.R.R. Tolkien. It was the centre of the Dark Lord Sauron, so sometimes people refer to Russia as Mordor, implying that only evil can be expected from there.Restoration of historic sites

People’s House

On 8 March, 2022, Russians launched aerial bombs on the centre of Okhtyrka. As a result, numerous historical monuments suffered damage, including the People’s House, an Empire-style building erected at the beginning of the 20th century and renamed the House of Culture in 1932. The building serves as the primary venue for events for residents of Okhtyrka and neighbouring settlements, housing departments of culture, tourism, youth and sports, as well as a local youth centre. On the eve of the full-scale invasion, the building underwent renovations to its lighting and sound systems, and a new sound recording studio was set up on its premises.

Although the facility is located in Okhtyrka, it formally belongs to the neighbouring Chernechchyna community, which has taken on the responsibility for its renovation. Ruslan Marchenko, one of the reconstruction coordinators, mentioned that significant progress had already been achieved by the beginning of summer 2022. This includes repairing the roof and preparing project estimates necessary to complete the restoration when peaceful times return.

“It’s not a matter of complete restoration because the time is not yet ripe for this, but rather about the preservation, “he says.

The community covered part of the work at their own expense and also posted information about the People’s House on the DREAM platform to find partners for further restoration. In 2024, their contribution helped to launch a multifunctional shelter, hosting events for informal education (including chess club and workshops), cultural events, art therapy for internally displaced persons, and more activities. This was made possible because young people participated in the project “Human Dimension: Effective Governance through Data and Community Engagement”, funded by Canada. USAID provided the People’s House with a generator, allowing the facility administration to hold events during power outages, caused by the Russian airstrikes.

DREAM

a Ukrainian one-stop platform that links war-affected communities with potential donors and delivers transparent reports on every stage of Ukraine’s post-war reconstruction projects.

Before the all-out war, the People’s House functioned as a venue for rehearsals and events. Today, it continues to fulfil this role, while also serving as a distribution centre for humanitarian aid to displaced people and military personnel. Ruslan points out that this was not the first time the building’s purpose had changed during wartime; during World War I, it was used as a hospital.

“It is now experiencing its third war, and perhaps the true value of this house lies in its embodiment of unity. […] Community residents know that if any aid is being collected for the soldiers, everyone should bring it to the House of Culture. In one case, we managed to collect a substantial amount of food from the entire Chernechchyna community in just half a day. Then we delivered it in a KAMAZ truck to the frontline for the soldiers of the 93rd Brigade, who were defending Okhtyrka in the first months of the [full-scale] war.”

According to Inna Novikova, the director of the local youth centre who is also involved in the restoration process, the building’s symbolism is further enhanced by the fact that it has served as a workplace for prominent figures such as actors Natalia Uzhvii and Amvrosii Buchma (prominent Ukrainian 20th-century actors – ed.), and writer Ivan Bahrianyi, best known for his novel Tiger Trappers.

“And now, for the youth of Okhtyrka — I know this because I work mostly with young people — it is a kind of symbol, specifically historical, literary, and cultural. And if we talk about any cultural events and discussions, this work [by Ivan Bahrianyi] is always mentioned. It is very pleasing that the youth are interested in all this and are trying to popularise this history.”

Ivan Bahrianyi

a Ukrainian 20th-century writer, essayist, and political activist, renowned for his works addressing resistance against totalitarian regimes. Repeatedly persecuted by the Soviet authorities, he escaped during World War II and engaged in extensive anti-Soviet activism while in exile.“Tiger Trappers”

a 1944 adventure novel that follows the story of a prisoner from Stalin’s terror who escapes from a train heading to the Gulag camps and survives in the Siberian wilderness. The novel received widespread critical acclaim in the West and was translated into several European languages.The Chykalo Family Hotel

In the 19th century, Oktyrka was home to the merchant and philanthropist Hryhorii Chykalo. Several buildings he funded have survived to this day, although their condition varies. Among them, is the Chykalo family’s guest house, which was once one of the largest buildings in the city, located at the heart of the city. Its two floors were constructed from stone: the first floor now houses a restaurant and a teahouse, while the second floor features rooms with a view of Rynok Square. The building, which was damaged during World War II, was later restored and repurposed as a garrison officers’ house. Today, it stands in disrepair, alongside many other local cultural sites. Local youth spearheaded the efforts to address this issue; among them is Vladyslav Liubarets, a cultural activist and representative of the community youth centre.

“If you stroll through the city centre, it is an open-air museum, with nearly every building being a historic site. Most of them are [now] used as shops, shopping centres, and other businesses. Their facades are somehow preserved, though not quite as they should be.”

Vladyslav believes that the restoration of the city should encompass its cultural and historic sites. If not preserved, these landmarks may vanish, significantly impacting the city’s identity and perception. He considers the settlement’s image and historical character among the key factors why people choose to stay there.

“Individually, these structures may seem insignificant and unnecessary, but in reality, they shape the unique architectural face of our merchant city. Therefore, if we gradually lose such buildings, we will simply erase our memory.”

slideshow

Indeed, even today, not all locals associate the building with Okhtyrka’s merchant history.

“Okhtyrka’s residents have different memories of this building. Some remember going there for discos, others associate it with watching movies; some recall its beautiful spiral staircase, while others remember it as a ruin.”

Vladyslav hopes that one day, the Chykalo family hotel will be transformed into an art space and a recreational hub for youth. He also hopes that businesspeople who purchase such buildings with the intention of converting them into commercial properties will realise that their historical significance adds value that can be leveraged to their advantage.