The current security situation in Sumy is eloquently illustrated by the headlines on a single page of local media, which might read: “Enemy drone downed”, “Constructing fortifications” “New podcast on city life launched”, and “Local craft festival to take place”. Living just 30 kilometres from the aggressor’s border, Sumy residents balance their efforts between investing in defence and funding city development.

In this article from the “Restoration” project, we explore how Sumy is coping with the aftermath of Russian shelling, constructing shelters, preparing for potential enemy attacks, and, more importantly, how it refuses to remain in a state of waiting for better times — life in the city continues to bustle.

We will speak with the director of a hospital damaged by the shelling, local government representatives, an architect involved in local projects, and the co-founder of a Sumy online magazine to understand how the city is recovering and developing during the war.

On shelters, medical care, and reconstruction

When local pharmacies closed at the beginning of the full-scale war, the Central City Clinical Hospital stepped in, distributing its medical supplies to Sumy residents. This support was particularly crucial for the elderly. Some patients even had to live at the hospital after finding out during their treatment that their villages had been occupied by the Russian army.

The hospital director, Valentyna Dominas, admits that on the first day of Russia’s full-scale invasion, she was worried she might not find any staff at the hospital. However, her fears were unfounded.

“On 24 February (the first day of the full-scale Russian invasion – ed.), our entire team showed up, and we’ve been working as a full team ever since. Almost no one left their post.”

Not only did the staff stay and continue working, but they also managed to launch a cardiac surgery department amid the all-out war. For this purpose, the team invited specialists to the hospital, and even started performing organ transplants while hostilities unfolded across the country.

“There are fewer and fewer Ukrainians, and we must fight for every Ukrainian [life].”

Despite repeated damage from Russian shelling, the hospital was repaired each time and continued to operate without interruption Valentyna recalls how, after the second shelling, the services, local authorities, and hospital staff came together to address the immediate consequences of the attack.

“There was about half an hour of confusion while everyone processed what had happened. Then, it became clear that we needed to collect the glass, remove the damaged windows, cover things up, and help wherever possible.”

The hospital has its development and improvement budget, part of which is allocated to fund repairs after shelling. Valentyna shared that it also covered the repairs to surgical equipment following an attack that damaged two operating rooms.

Deputy Mayor Stanislav Poliakov adds that the city receives substantial support from charitable organisations that either assist on-site after shelling or handle part of the restoration work. These organisations include Dobrobat, World Central Kitchen, Right to Protection, Caritas, Proliska, and others, which allow local authorities to focus on broader issues without spreading their efforts and resources too thin.

At the same time, Oleksii Drozdenko, the head of the Sumy City Military Administration, emphasises the need to properly coordinate all those willing to aid in the restoration efforts. He recalls instances when volunteers arrived at the site of enemy impact faster than the services that could assess whether it was safe to be there.

“Everyone is now well-coordinated, and everything works absolutely smoothly. When I arrive, there are people to work with and those who help. It’s a characteristic of ours: everyone rushes to the site of impact, rather than scattering.”

According to Oleksii Drozdenko, in 2024, the city experienced an increase in Russian drone strikes, the use of guided aerial bombs, and missile attacks. He says that the initial work at the site of impact begins immediately, sometimes even at night, to clear debris and restore essential services such as heat, electricity, gas, and water supply.

Military Administrations

temporary local executive authorities in Ukraine, that were established on the first day of the full-scale invasion to oversee defence, public safety, and order during the period of martial law.

He reveals that the city authorities are actively expanding their network of shelters. Currently, Sumy has equipped around 300 shelters, with additional ones undergoing repairs, documentation, and approval by the State Emergency Service of Ukraine (Ukraine’s fire and rescue service – ed.), gradually increasing their number.

“As for our overall strategy, we’ve chosen to invest specifically in defence.”

Oleksii admits that in 2022, the military administration took a more superficial approach to equipping shelters due to the urgency of the situation; to quickly increase the number of shelters, they simply cleared out basement spaces. Now, local authorities are intentionally allocating part of the budget to construct shelters that meet necessary requirements, such as ventilation, generators, heating, water supply, and sewage system. Those attached to schools or hospitals are equipped to continue teaching or providing medical care without having to wait until the end of an air raid.

“For instance, [during an air raid] the maternity hospital continues providing consultations with patients in the shelters. They have the necessary equipment, and it’s even possible to deliver babies there, which has already happened. The same applies to other healthcare facilities. In other words, the shelters serve dual purposes. The same goes for schools: it’s impressive to see how entire classes are organised [in the shelter].”

The hospital shelter also contains properly equipped operating rooms, adds Valentyna.

“We realise that people we accommodate are not simply Sumy residents but patients in need of care, and emergencies can arise at any moment. […] There is a large supply of medication, the capability to accommodate bedridden patients, and all the necessary conditions to ensure that people feel not only safe but also as comfortable as possible.”

Valentyna refers to the shelter as a “small medical state” capable of providing a wide range of medical assistance. Deputy Mayor Stanislav Polyakov states the general strategy for medical facilities is making shelters as autonomous as possible. As of mid-2024, this goal has been achieved almost everywhere, with two more shelters currently in the final stages of completion. The local budget remains the key source of funding for such projects; however, some facilities have been renovated with targeted financial assistance from the state budget.

Stanislav mentions that representatives of the Sumy local government visited Borodianka (a Kyiv suburb heavily damaged during the early stages of the full-scale invasion – ed.) to learn from their experience of working with international partners, including Lithuania. They now plan to construct a shelter at an educational institution with the same partner, replicating the approach used in Borodianka.

An architect’s perspective

Olena Dovhopolova is an architect, interior designer, and founder of the Inakshi architects bureau. Currently, her professional interests include the development of public spaces and the use of biodegradable building materials made from technical hemp.

Originally from Donetsk (one of the first Ukrainian cities occupied by Russia in 2014 – ed.), Olena has been living in Sumy since 2014, where she has since developed a deep sense of home.

“This is a city of hidden opportunities. In fact, this phrase is even featured in our development concept. And it becomes clear only after you get to know the city a little better.”

She says that the proximity to the Russian border inevitably affects Sumy: investments are primarily directed towards defence, while niche development initiatives remain underfunded. However, the community keeps making long-term plans and implementing timely projects. For example, Olena was involved in the Urban Coalition Ro3kvit — a group of over 100 experts from Ukraine and abroad developing methodologies for Ukraine’s further growth and recovery. Together, they presented a housing project for internally displaced persons (IDPs) that allows them to stay in the community rather than merely viewing it as a transit point. Olena believes that the issue of providing decent housing remains inadequately addressed, as the influx of people has led to many solutions being temporary.

Olena points out that while Sumy has many architectural associations, the real issue is whether people actually consult them before launching architectural projects.

“Clients frequently attempt to save money on projects and develop designs on their own. They simply avoid working on load-bearing structures to bypass the need for approvals. They rely on Pinterest for designs.”

Olena notes that projects developed by young specialists are often volunteer-based and frequently remain unimplemented.

“Professional teams are united by an internal philosophy and a desire not just to make money, but to live in a city where it’s not only acceptable to live but also a great place to spend time. It’s fascinating to watch how these communities form: starting with just two or three people, then growing to 10, 20, 30 people within a month, and finally evolving into a kind of movement.”

Olena points out that while Sumy has many architectural associations, the real issue is whether people actually consult them before launching architectural projects.

“Clients frequently attempt to save money on projects and develop designs on their own. They simply avoid working on load-bearing structures to bypass the need for approvals. They rely on Pinterest for designs.”

Olena notes that projects developed by young specialists are often volunteer-based and frequently remain unimplemented.

“Professional teams are united by an internal philosophy and a desire not just to make money, but to live in a city where it’s not only acceptable to live but also a great place to spend time. It’s fascinating to watch how these communities form: starting with just two or three people, then growing to 10, 20, 30 people within a month, and finally evolving into a kind of movement.”

Among the examples of communities seeking to influence the city, Olena mentions the “Sumy of the Future” initiative, which creates projects for street reconstruction and developing embankments.

Olena believes that the architecture market in Sumy is still developing. Clients often do not fully understand the value of work and solutions offered by specialists. However, her experience proves that people become more receptive when the importance of certain decisions is clearly explained.

“We turn down projects when clients don’t understand why we are doing something, but such cases are extremely rare. For example, we recently managed to design a small café – just 30 square metres – and included an accessible restroom. That proves that, with the right approach, it’s achievable. When clients are properly informed, they never oppose these considerations.”

Regarding accessibility in Sumy, Olena notes that progress largely depends on the initiative of concerned individuals.

“It’s moving towards greater accessibility, but only when someone actively drives this idea and concept. When momentum stalls, it remains stalled.”

Olena believes that the surroundings of Sumy offer significant potential for innovative construction, particularly through the use of biodegradable materials. This approach not only benefits the environment but also considers the region’s agricultural nature and current conditions.

“We don’t have enough forests; we’ve already exhausted this resource. We simply need an alternative.”

Olena believes that implementing such initiatives requires active promotion, and Sumy has a platform for this. For instance, the independent Sumy-based media outlet Tsukr has gained popularity far beyond the city.

“I think activists working on their own tasks and topics need to speak out more, be visible in the media, present their work everywhere, and basically shout about the ideas they are passionate about.”

Youth forge of ideas and events

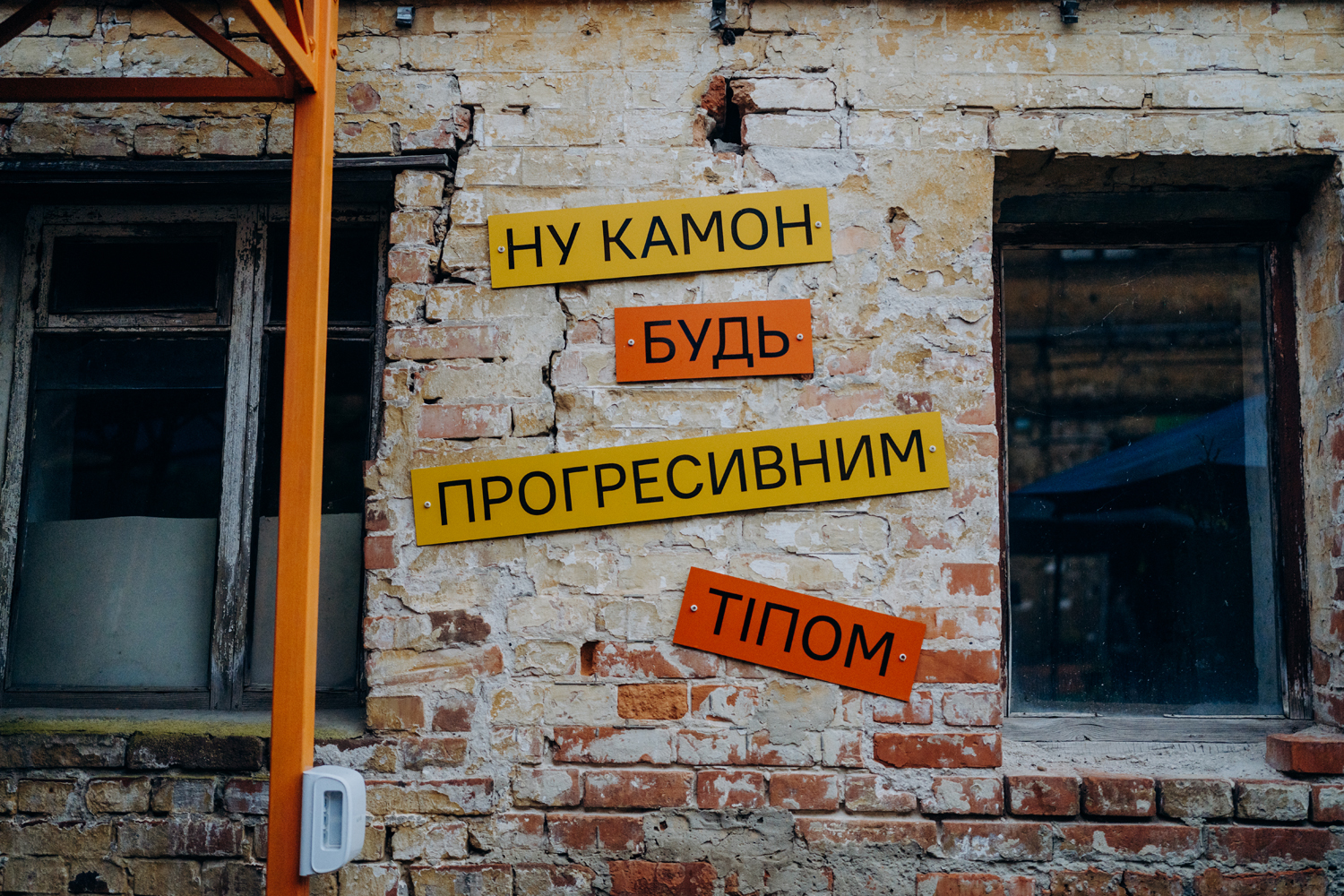

Dmytro Tishchenko is a journalist and activist with a deep understanding of his city and a direct impact on its development. In particular, he contributes to local projects such as the media outlets Tsukr, and initiatives like “Hub on Kuznechna”, and “Courtyard on Kuznechna”.

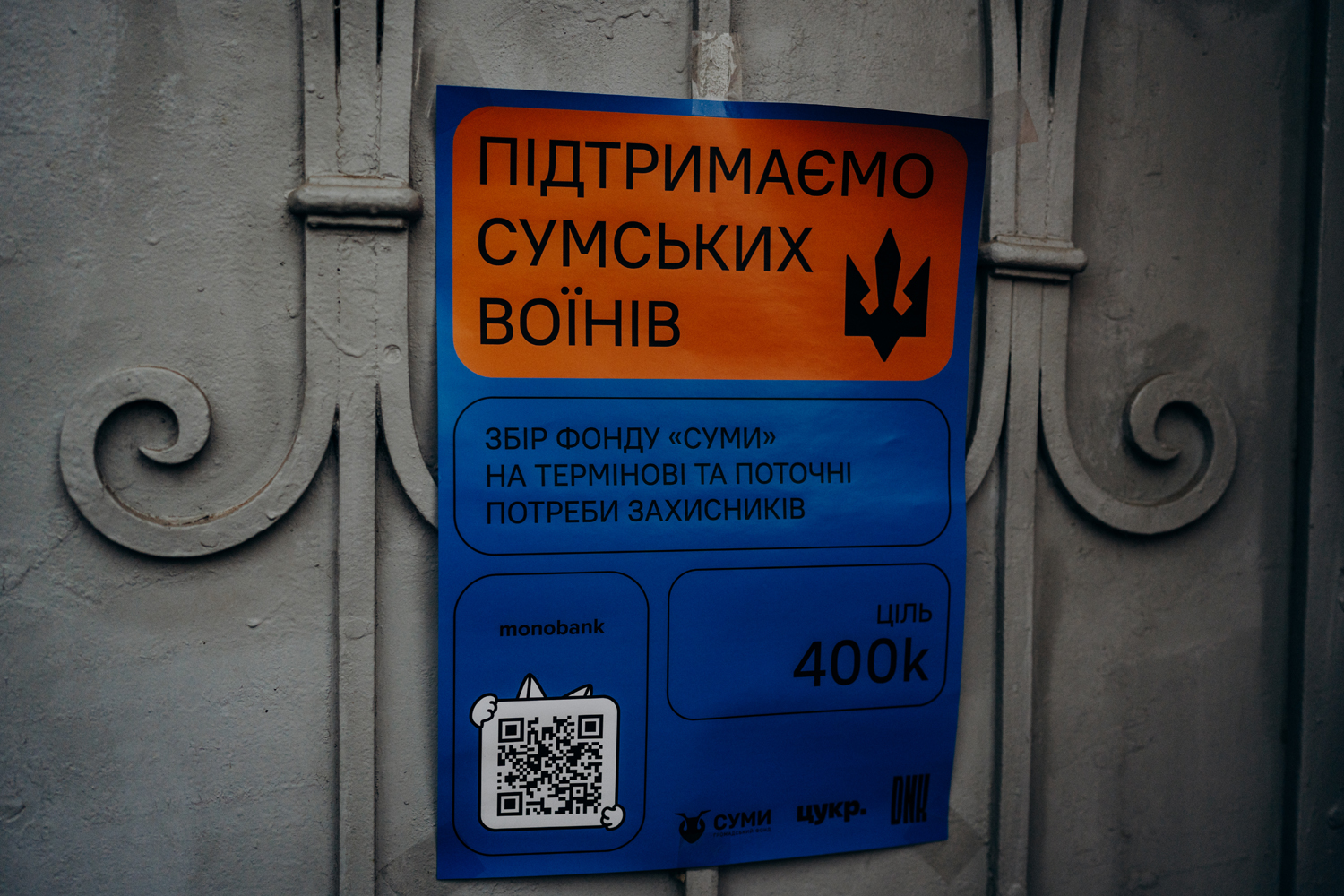

Since 2014, Kuznecha street has been home to the “Sumy” charitable foundation, which initially supported Sumy residents participating in the Anti-Terrorist Operation (ATO). Nearby, there was a large, neglected state owned by the state. It was owned by the state. In 2017, Dmytro and his colleagues reached an agreement with the local authorities to repurpose this space for holding events, meetings of civic activists, and other community activities.

“We took inspiration from a format in Kyiv called ‘networking for change-makers.’ We wanted to replicate something similar in Sumy and needed an open space — we thought it should be outdoors. During our search for locations, we repeatedly approached the administration, who said, ‘Look, there is a courtyard there – enhance it and hold your events.’ ‘Enhance it’ was an understatement, as it had been accumulating layers of garbage for probably 15–20 years.

ATO

the official designation for the Ukrainian military operation in the Russian-occupied Donetsk and Luhansk regions from 2014 to 2018. In 2018, it was succeeded by the Joint Forces Operation (JFO), which continued until the full-scale Russian invasion in February 2022.

The most active period was 2018 and 2019, where volunteers were busy organising the space, and events were taking place one after another.

“In the first year, we almost went crazy – we held 150 events. We really ‘treated’ people with whatever they wanted because they were hungry for information on various topics. This was particularly true during the decentralisation reform, and all of these issues were discussed here.”

Decentralisation reform

one of Ukraine's most extensive reforms, launched in 2014 to transfer power, financial resources, and responsibilities from the central government to locally elected self-government bodies, such as city councils and their leaders.Dmytro mentions the drastic decrease in activities during the 2020 – 2021 pandemic, which was further exacerbated by the full-scale Russian invasion in 2022.

“On the morning of 25 February, I took the last photo of the hub in its original state because soon after, it was immediately repurposed for various humanitarian needs.”

After the start of the Russian invasion, all hub activities – from making Molotov cocktails to sorting medicines and food – sought to support local civilians and the city’s defenders.

“When the Russian troops finally retreated (from the north of the country — ed.), we admitted that we needed to continue operating rather than just sitting on the remaining canned tomatoes, which had nowhere else to go,” Dmytro recalls.

The team decided to reconsider their next steps and realised that after everything the community had been through, there was a need for people to see each other and come together. Initially, they focused on conducting informative and educational events, like discussing the history of Slobozhanshchyna and Russification. Later, the hub added a cultural component, and now the yard regularly hosts live music, stand-up comedy, and theatre performances. The hub has also become a space for recording podcasts and lending equipment to various projects. In 2022, the team introduced a form allowing local residents to suggest events. However, by 2024, this became increasingly challenging due to security conditions and financial limitations stemming from dependency on grantors, and difficulties in expanding the donor community as most people prefer directing their funds toward military needs.

“It operates on a minimal budget, but it’s a respectable kind of minimal, where you can still afford to host a concert or hold a business meeting,” Dmytro says.

Responding to a question about interactions with local self-government, Dmytro explains that they generally manage to find common ground with certain officials who are interested in specific issues. For instance, during our filming in the summer of 2024, both the public and the authorities were preparing to discuss the information space.

“It won’t immediately result in any groundbreaking solution, but starting to synchronise our efforts and having these discussions is extremely valuable. There is no goal to achieve a grand outcome, like making everyone friends or turning the world upside down. Instead, it is about introducing people to each other.”

The initiative originated from the local media outlet Tsukr, which emerged during the pandemic when, as Dmytro puts it, “it was the only way to connect with people who wanted to see something positive happening in the city.”

“Now it’s a kind of self-governing community. People support us financially, gradually become more involved, and come together. Some submit petitions, while others invite government representatives to meetings.”

Dmytro observes that crises often create opportunities for proactive initiatives and serve as catalysts for change. For instance, in 2019, the media outlet Tsukr bore little resemblance to traditional journalism. By 2020, they started using simple language to explain the course of the pandemic. Then, in 2022, they almost unintentionally evolved into communicators focused on highlighting the needs of the local community.

“We tried to keep the spirit of resilience alive. As sentimental as it might sound, people needed to hear, ‘We are here, we are working, we are doing this. Let’s work together, join us, send donations, we will purchase whatever is necessary.”

According to Dmytro, their goal was to maintain a pro-Ukrainian information space.

“Volunteers would come and say, ‘Open the hub for us; we are setting up a headquarters here.’ Others would say, ‘Let us moderate the chat because people are panicking.’ Psychologists and other helpers would come, and our task was bringing all these components together into something functional, a cohesive organism.”

Dmytro believes that while focusing on security is justified, the concept of investing solely in defence does not resonate with him. He illustrates his perspective with an example from March 2022, where a stand-up show was held in a bomb shelter. On one hand, Dmytro acknowledges the paradox of organising such an event in the city under threat, yet people gather to laugh, and the organisers invested time in it. On the other hand, he highlights the indescribable sense of community and unity that emerged from this experience.

“At the same time, it’s also a huge middle finger to the Russians trying to encircle, stop, or occupy us, while we come together to laugh at them. I’m sure they don’t directly watch this content or take offence, but it’s about how we, as a community, feel at the moment.”

Another poignant moment occurred in August 2023, which Dmytro shared on his social media. After a performance at the “Courtyard on Kuznechna”, a soldier took to the stage. He had returned home for a day, while his family was abroad and unable to meet him. He expressed his gratitude, stressing the importance of culture, and thanked everyone for providing him with a place to spend that day.

Dmytro claims that culture generally doesn’t require massive budgets, and he jokingly adds that sometimes it’s enough just not to interfere. The presence of cultural activities, opportunities to relax and recharge significantly impact locals. If venues close, events stop, and landmarks are left unrepaired, it can affect the mental state of those remaining in the city and may even signal that it’s time to evacuate.

“We spoke with a coffee shop owner, and he said, ‘I realise my responsibility. Right now, I’m not [just] an entrepreneur, and what I do is a litmus test.’ If people see the coffee shop closed tomorrow, [they’ll think], ‘That’s it, it’s time to leave.’”

When discussing his vision for the future of Sumy, Dmytro emphasises two key concepts: cosiness and vibrancy.

“We are doing everything we can to keep Sumy as cosy as it is. I think many locals will understand what I mean, and for those who are not from here, it’s something you need to experience firsthand.

I believe that Sumy needs to find a new way to be better than the big cities. Small towns have many advantages, but we haven’t fully learned to recognise them because we tend to view ourselves as the periphery. We are combating this inferiority complex.”