The multimedia online platform Local History explores Ukraine’s past and present while promoting history through print magazines and online materials. These stories are unique discoveries from archives, conversations with descendants of historical figures, eyewitnesses, and experts. Here is a piece about the remarkable Ukrainian Stepan Zoshchuk, originally created by Local History and translated by the Ukraїner International team.

Written by

Candidate of Historical Sciences, researcher

As a young man, Stepan Zoshchuk was seen as a promising football player, but he chose a career in medicine instead. He began his practice in Poznań (a city in Poland – ed.), and three decades later, he found himself in Addis Ababa, where he befriended Emperor Haile Selassie. One of Zoshchuk’s key recommendations to his patients was to give up meat. Who knows — perhaps it was vegetarianism that helped him live a long and eventful life.

Football player turned doctor

Stepan Zoshchuk was born in Kraków, where his father — a former officer of the Austrian army — worked as a postal official. He had two brothers and a sister. After World War I, the family moved to Kolomyia (a city in the west of Ukraine – ed.). There, Stepan completed primary school and attended a Ukrainian gymnasium.

During this time, he was actively involved in Plast (Ukraine’s oldest scouting organization, founded in 1911 – ed.), joining the 77th Ivan Bohun Scout Troop and serving as a medic at the Sokil summer camp. After a year of military service, Zoshchuk returned to Kolomyia, where he and his brother Ivan played for the Sokil football team.

His friend Volodymyr Hankivskyi pursued a career in medicine, and Stepan decided to follow the same path. At the time, it was nearly impossible for a Ukrainian to enroll in the medical faculty of the nearby Lviv University, so he had to go to Poznań, Poland. In 1935, he was among 12 Ukrainians who began their studies at the university there.

Plast

is a Ukrainian scouting organization dedicated to the comprehensive, patriotic education and self-development of Ukrainian youth.

Collage by Bohdana Davydiuk

In his first year, Zoshchuk became an assistant to Professor Stefan Ruzhytskyi, who was setting up the Anatomy Museum. He also joined the Ukrainian Student Community, where he founded a Medical Section. Its seminars covered more than just medical topics — Zoshchuk himself gave lectures on subjects such as “The Rotation of Governments in History (Monarchy, Oligarchy, Triumvirate, Democracy, Communism, Dictatorship, and Anarchy)” and “Zelenyi Klyn as Ukraine’s Natural Colonies.”

He also took part in the Eucharistic Catholic Congress, which brought together Greek Catholic bishops from Halychyna and Volyn. During vacations, he visited his parents in Kolomyia and continued playing football.

Escape from the Gestapo

In the summer of 1939, Stepan Zoshchuk graduated with a medical degree and a certificate allowing him to work as a sports doctor. He then began a private medical practice in Poznań. Even at that time, he recommended that his patients give up meat.

That same year, he married Iryna Prysnivska, a Ukrainian woman who had trained as a midwife. Soon after, the couple had a daughter, Odarka-Svitlana, and a son, Askold.

World War II did not stop Zoshchuk from serving the community. He founded and led a local branch of the Ukrainian National Union (UNO), which included over 40 members. The UNO (an early 20th-century political and cultural organization founded to advance Ukrainian self-determination – ed.) organized sporting events, New Year’s celebrations, Shevchenko’s Day (the birthday of Ukraine’s largest 19th-century writer considered a national poet – ed.), Mother’s Day, the anniversary of the Battle of Kruty, and Unity Day. A publication called Holos described one such event: “The celebration included a lecture, the play The Child’s Secret, and recitations. The play was staged on a beautifully arranged set and performed so well by the children that it made a deep impression on the adults. Everyone appeared in traditional costumes, with girls wearing wreaths on their heads and boys with sabres at their sides. The lecture and recitations were also well executed, if not outstanding. After the celebration, there was a reception for the children.”

The Battle of Kruty

was a fight that took place on 29 January 1918, near Kyiv, where Ukrainian forces, mostly students, defended the newly-founded Ukrainian People's Republic against a much larger Russian Bolshevik (Communist) army.

A collage by Bohdana Davidiuk

This activity attracted the attention of the Gestapo. When he learned that he was facing arrest, Stepan moved to Vienna, where he got a job at the Second Surgical Clinic of the University of Vienna. Over the next decade, he managed to work in almost all areas of surgery, from minor and urgent surgery to major operations on internal organs and limbs. This was reflected in his official qualifications: he received a clinical assistant degree and a certificate of specialisation in general surgery and urology. He had a short internship at the French military hospital in Feldkirch.

While living in Austria, Zoshchuk did not give up his public activities. He was one of the leaders of the training camp of the Wives of Ukrainian Nationalists in Seibersdorf Castle. Odarka Svitlana repeatedly participated in the festive events of the Ukrainian community, where she sang and recited poetry. In 1961, the doctor’s daughter, dressed in a folk costume and holding a blue and yellow flag, served as a guard of honour during the unveiling of a memorial plaque on the house where Ivan Franko (a prominent Ukrainian poet, writer, and public figure – ed.)

Baghdad – Addis Ababa – Nairobi

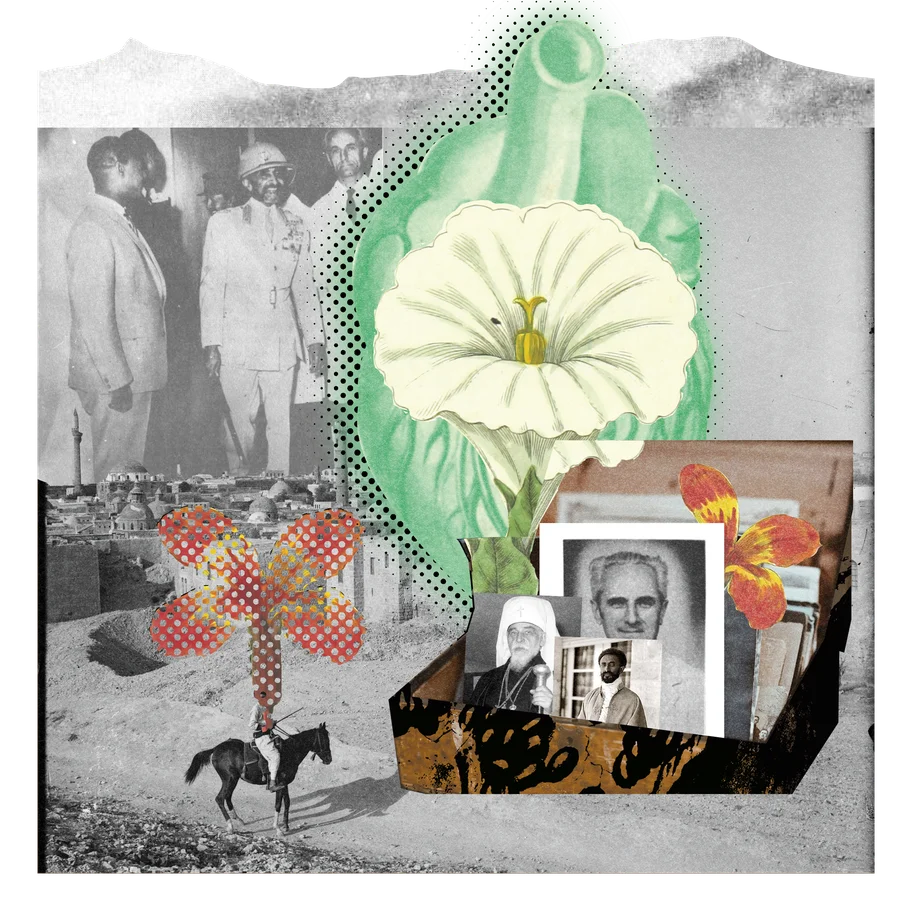

The restless doctor gladly accepted job offers in the most exotic corners of the world. In 1956, he moved to Aleppo, Syria, where he worked at the Al Kalimeh and Al Agli hospitals. He communicated with the country’s president, Shukri Kubotli, and participated in a congress of Arab doctors in Baghdad.

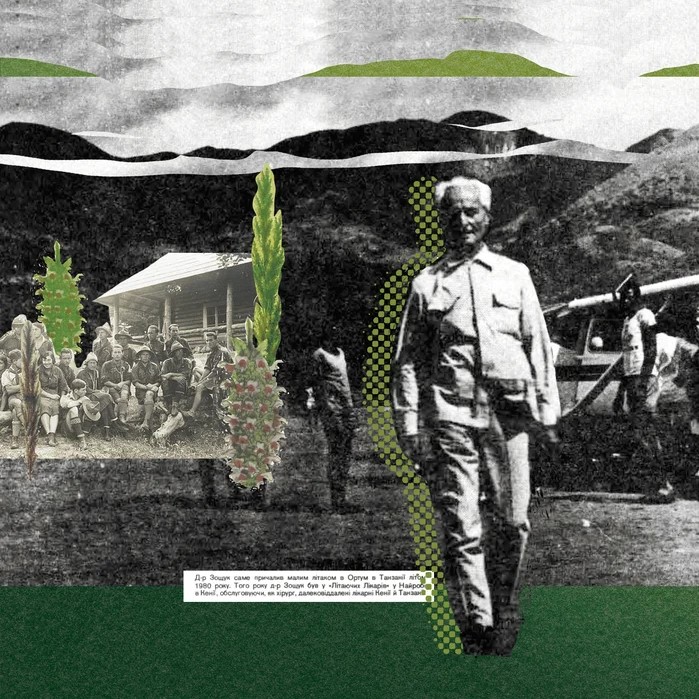

In the late 1960s, Stepan Zoshchuk worked at the hospital of the Imperial Allied Military Forces in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. He was invited there by Emperor Haile Selassie. The Ukrainian advised the monarch and his family. He travelled a lot. For example, he accompanied Austrian climbers when they conquered the highest peak in the country, Ras Dashen. He overcame the difficult ascent more easily than his younger companions, as he claimed, precisely because he ate only plant-based food.

In 1974, a coup occurred in Ethiopia, and Haile Selassie was forced to flee abroad. Stepan Zoshchuk then took a position at the French-Ethiopian Society’s hospital for the Addis Ababa–Djibouti railway. A few years later, the war between Ethiopia and Somalia broke out, and he worked as a surgeon in a military hospital. He then became the director of a leprosy hospital in Gambo, Central Africa, and later worked as a surgeon at a hospital in the Kenyan town of Tabaka. Zoshchuk also worked as a surgeon for the organization “Flying Doctors” in Nairobi, the capital of Kenya. In addition, he corresponded with the Greek-Catholic Patriarch Josyf Slipyi, who had been imprisoned in Soviet labor camps for many years (Slipyi was imprisoned by the Soviets for 18 years before moving to Rome and becoming a leading advocate for Ukrainian Catholic rights and independence – ed.) and had moved to Rome. Zoshchuk visited the Patriarch twice and was with him in his final days.

The 1974 coup in Ethiopia

was a key event that led to the overthrow of Emperor Haile Selassie I and the establishment of the military dictatorship of Derg, putting an end to the centuries-old monarchy.A book about healthy nutrition

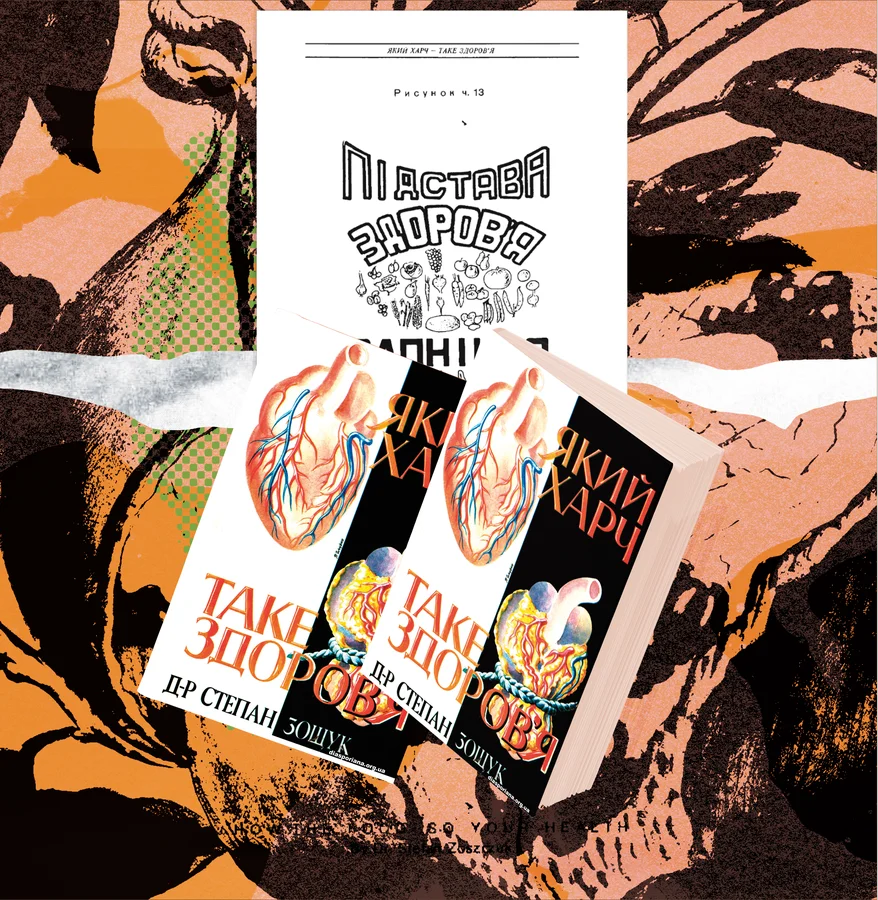

Throughout this time, the doctor’s wife and children lived in Vienna. In the early 1980s, Stepan Zoshchuk returned to his family but not for long. Friends invited him to Toronto, and he couldn’t refuse. There, over several years, he worked on libraries, culminating in the publication of the book “What You Eat Is Your Health”. It was printed in Brussels as part of the Shevchenko Scientific Society series in Canada, with a print run of 2,000 copies. The introduction was written in German by Swiss scholar Ralph Bircher, the son of Maximilian Bircher-Brenner, one of the pioneers of dietary medical research. “This book should serve as a guide to nutrition for all ages, especially for young people starting families, and most importantly, for future mothers who bear responsibility for the health of future generations,” wrote Dr. Mykola Hrushkevych, a native of Stanislaviv (present-day city of Ivano-Frankivsk in the west of Ukraine – ed.), who ended up in the USA after World War II.

Collage by Bohdana Davydiuk

The author encouraged readers to eat vegetables and fruits while drastically limiting meat consumption. He linked the death of Taras Shevchenko to improper nutrition, stating, “We tend to attribute his premature death to exile (Shevchenko was sentenced to 10 years of exile in remote parts of Russian Empire for advocating Ukraine’s self-determination– ed.), but a detailed review of his diet, particularly meat, fish, and vodka, proves otherwise. This diet destroyed his kidneys, liver, and heart.” He also had criticisms of Ivan Franko and Lesya Ukrainka (a leading Ukrainian female writer of the early 20th century – ed.), stating: “One can justify the ‘reasons’ for their premature deaths in many ways, but their diet cannot be justified, and this is what led them, along with many other prominent figures of their time and now, to an early grave.”

One could debate the practicality of these recommendations, but one undeniable fact is that Stepan Zoshchuk, following his own dietary advice, lived to the age of 92. He passed away in Feldkirch (a town in the west of Austria – ed.) and was buried at the Gersthof cemetery in Vienna, where his wife had been resting for 16 years. At the end of the 2010s, the lease on the plot expired. The Austrian scouts managed to secure another plot at the same cemetery, and that’s where the Zoshchuks were reburied.