In collaboration with the “Where are our people?” project by Ukrainian non-profit PR Army, the Ukraїner team is investigating Russia’s crimes against Crimean Tatars throughout history and their enduring impacts today. In this article, we provide a brief history of the origins of the indigenous people of Crimea, discuss the occupation of the peninsula by the Russian Empire and the Communists, and most importantly, investigate the preconditions and ongoing consequences of the 1944 deportation of Crimean Tatars by the Soviet regime.

The Crimean Tatars (Qırımlı) have existed as a people for many centuries. In Crimea, they developed their own approach to statehood, their relationship with nature, and their unique cultural landscape and traditions. Crimea is deeply infused with Crimean Tatar life, yet several waves of occupation, centuries of repression, the genocide of 1944, the ongoing war of aggression, and Russian occupation aim to sever all ties between the indigenous people and their homeland.

The Russian Empire deliberately created unbearable living conditions for the Crimean Tatars, culminating in their mass emigration and eventual deportation in 1944. The consequences of this crime persist to this day. Depriving an indigenous people of their homeland is not merely a matter of physically relocating them — it is an act of violence that profoundly disrupts their lives and destinies. Overcoming the aftermath requires years — sometimes centuries — of rebuilding national memory, history, culture, and often the natural and social ecosystems of the homeland from which the indigenous people were uprooted. It forces them to search for their identity, piecing it together from fragments of history and memory that the oppressors failed to erase.

Origins of the Crimean Tatars

The Crimean Tatar ethnicity developed over thousands of years. The formation of their anthropological type, language, character, traditions, religion, and way of life was influenced by numerous factors. This complex process involved many peoples and tribal unions that inhabited Northern Prychornomoria and the Crimean Peninsula at various times. The Tauri, Cimmerians, Scythians, Sarmatians, Alans, Hellenes, Goths, Huns, Khazars, Pechenegs, Kipchaks, Mongols, and many other tribes can all be considered ancestors of the modern Crimean Tatars. Together, these groups laid the foundation for the future of the Crimean Tatar nation.

Today, the three main sub-ethnic groups of Crimean Tatars — highlanders and foothill residents (crh. ortayulak), steppe dwellers (crh. noğaylar), and the population of the southern coast (crh. yalıboylu) — reflect a blend of characteristics from other sub-ethnic groups that historically inhabited the territory of Crimea.

The Crimean Khanate: an independent Crimean Tatar state

The Crimean Tatars became the dominant ethnic group in Crimea by the mid-15th century. In 1441, they established their own independent state, the Crimean Khanate.

The Crimean Khanate was a vast territory encompassing the Crimean Peninsula and the lands of Northern Prychornomoria. The state was founded by Hacı I Geray, who united the powerful and influential families of the Crimean nobility and established the ruling dynasty that would govern for centuries.

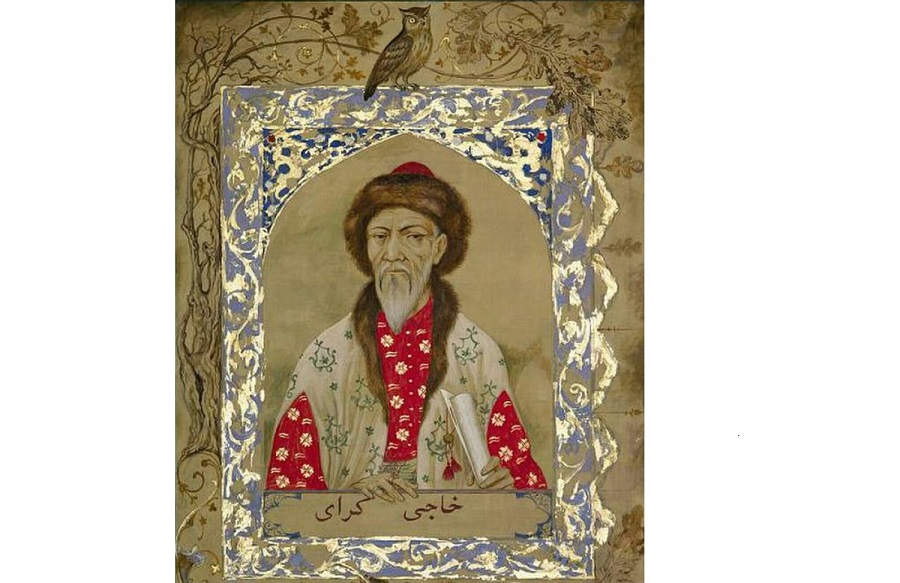

Hacı Giray, the founder of the Crimean Khanate, depicted in a portrait based on old Ottoman miniatures. Portrait by Yurii Nikitin for O. Haivoronskyi’s book Lords of the Two Continents.

Hacı I Giray encouraged the development of agriculture, crafts, and trade, addressing the population’s economic needs. He also initiated a series of administrative, economic, and cultural reforms that allowed the state to develop peacefully. The Crimean Khanate harmoniously combined elements of Turkic, Mongol, Islamic, and European traditions.

The painting “Yevpatoria (Kezlev)”, by Carlo Bossoli, 1856. Image source: Wikipedia.

In 1768, in an alliance with the Ottoman Empire, the Crimean Khanate began a war with the Russian Empire. The war formally ended with the signing of a peace treaty in 1774. However, the Russian Empire violated the terms of the armistice by failing to withdraw its troops from the territory of the Crimean Khanate. Three years later, it provoked a popular uprising against the ruling Crimean Khan, Şahin Geray, and sent additional troops to the peninsula under the pretext of helping to suppress it. The Russian Empire occupied Crimea shortly afterward.

The signing of the Kuchuk-Kainarji Treaty, an engraving from the late 18th century. Image source: Wikipedia.

The first Russian occupation and the deportation of Crimean Tatars

19 April, 1783 is considered the date when the Crimean Khanate officially ceased to exist. On this day, the occupying country signed a manifesto stating that “the Crimean peninsula, Taman, and the entire Kuban side are accepted into the Russian state”. The text of the manifesto itself highlights the colonial, expansionist nature of the Russian Empire’s policy towards the neighbouring state, demonstrating its reliance on forceful methods, distortion of facts, and outright lies. An example of the latter is the supposed abdication of the throne by Şahin Geray. In reality, there was no abdication, and certainly no transfer of Crimea to the Russians by the last Crimean Khan. Similarly, the population of the Khanate did not swear allegiance to the new authorities. Moreover, news of the manifesto only reached Crimea several months after it had been signed.

Commemorative imperial medal marking the annexation of Crimea. On the top of the reverse, it reads “The Consequence of Peace”, and at the bottom, “Annexed to the Russian Empire without Bloodshed”.

Crimea was important for the Russian Empire in economic, political, geopolitical, military, and ideological terms — it was a symbol of the empire’s expansion. Its annexation had been planned for several years. The Russian Empire used all available tools, from propaganda to physical destruction, to reach this goal. The Crimean Tatars themselves called the period of annexation “the black century”. The people lost their state, land, privileges, and right to freedom, yet they had no intention of submitting to the occupiers. The outbreaks of armed uprisings that occurred during the annexation of Crimea continued afterward. Prince Grigory Potemkin (a Russian military leader who played a key role in the expansion of the Russian Empire in the late 18th century. – ed.), under whose control the lands of the former Crimean Khanate fell, ordered the destruction of all those who opposed the new authorities.

Punitive squads were brought to the peninsula. Repressions targeted not only the rebels but also their families — women and children were killed. Those suspected of working against the empire or sympathising with members of the Geray dynasty were sentenced to death. Officially, over 30,000 Crimean Tatars were killed in 1783, although the actual death toll was much higher.

At the end of the eighteenth century, Russian empress Catherine II tasked imperial scholars with justifying the 1783 occupation of the Crimean Khanate and proving that the Crimean Tatars had no grounds to claim special rights in Crimea. In the Russian Empire, historical science, which should have remained impartial and objective, was largely used as a tool of ideological influence. Historians of the time created a pseudo-historical, manipulated version of the origin of the Crimean Tatars, deeply embedded into the empire’s imperial worldview. They claimed that the Crimean Tatars were descendants of the Mongols who had come to conquer Crimea in the first half of the thirteenth century, and therefore, they couldn’t be indigenous to the peninsula.

The Russian Empire sought to create a situation in which the Crimean Tatars would leave their homeland voluntarily. Russian officials were granted the right to interfere in the activities of Muslim communities by strictly regulating the implementation of their religious rules and norms. If the officials disapproved of something, they accused religious leaders of treason. They also forcefully closed mosques: while there were about 1,500 mosques in Crimea at the end of the eighteenth century, that number had halved by the nineteenth century.

Crimean Tatar school (medrese), 1910. Image provided by the authors of the text.

At the same time, the Crimean Tatars faced another problem: the massive theft of their land. Prince Potemkin personally led this process, granting himself 85,000 hectares of land. The other largest land masses of the former Crimean Khanate were acquired by Russian nobility, landowners, dignitaries, officers, and even retired soldiers. Each of them had to settle at least 13 peasant families in their lands, which is how serfdom spread on the peninsula. In total, between 1783 and 1854, almost 46,000 Russian serfs were relocated. Potemkin encouraged this practice, as his primary goal was to populate the occupied lands with as many Russian subjects as possible. In addition to Russians, foreign colonists were also actively invited to Crimea, making up 11% of all immigrants. In exchange for citizenship in the empire, foreign immigrants were given large plots of land, exempted from conscription and taxes for 30 years, and granted the right to engage in trade. The Russian authorities continued to distribute Crimean lands until the second half of the nineteenth century, when they became scarce and, as a result, a commodity.

Serfdom

A feudal practice that established the incomplete ownership of peasants by the feudal lord. Serfs did not own their homes and were obligated to work for their master for life. Serfdom existed in Russia from the mid-17th century until its abolishment in 1861.Due to the massive theft and redistribution of land, Crimean Tatars found themselves with the status of landless tenants. In just ten years of occupation, more than 350,000 hectares of fertile land were taken away from them. The local population was forbidden to use the forests and was charged for the use of mountain gardens, water, pastures, firewood, and hay. Prior to the 1783 Russian occupation, people had been able to use all of this freely, as it was the property of the jamaat, or local Muslim community. These discriminatory practices, along with many other conditions of the occupation, led to several waves of mass emigration of Crimean Tatars to the neighbouring Ottoman Empire, which became a real demographic crisis for the people.

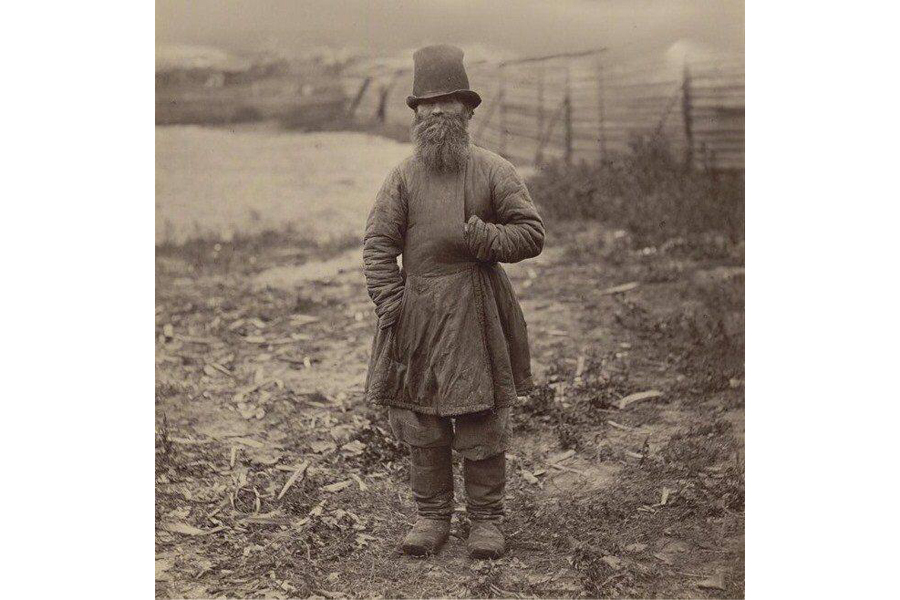

Russian serf, second half of the 19th century. Photo: J. X. Raoult.

The first wave of emigration intensified in the second half of 1783, when approximately 50,000 Crimean Tatars fled, according to Crimean Tatar political activist Amet Özenbaşlı. The following year, as a result of the migration, the historical provinces of the Crimean Khanate outside the Crimean Peninsula, such as Taman (present-day Russia), were significantly depopulated. As soon as the Crimean Tatars began to leave their homeland, a decree was issued to confiscate the homes of those considered “non-peaceful” Tatars — those who “refused to endure the benefits of Russian rule”.

The Russian “Greek Project”, a plan by the Empress Catherine the Great that envisaged the destruction of the Ottoman Empire and the revival of the Byzantine Empire, centred in Constantinople, provoked a new war between the Ottoman Empire and Russia in 1787. The war gave the Crimean Tatars hope of restoring their statehood, but this opportunity was lost. Military operations were slow and ultimately culminated in the Treaty of Jassy, which further solidified Russian control over Northern Prychornomoria and Crimea. Following this, the Crimean Tatars continued their mass migration to the Ottoman Empire.

Caricature “Imperial Step”, 1791. Image source: The British Museum.

Their resettlement was facilitated by the Russian government. In 1803, Russian Interior Minister Count Kochubei officially ordered the mass distribution of exit passports to Crimean Tatars. Even those who had no intention of leaving their homeland were forced to sell their property and prepare to leave Crimea. However, this disaster was averted by the arrival of Duke of Richelieu from Odesa, where he was governor. Richelieu compiled a detailed report for the government that portrayed the Crimean Tatars in a positive light – not out of empathy for them, but due to their essential role and the skills they had gained through centuries of farming the land. The following year the issuance of exit passports was suspended. However, the Crimean Tatars who hadn’t left still remained under the total supervision of Russian officials. Additionally, the Russians implemented harsh measures against the indigenous Crimeans. In 1827, a decree was issued to Russian landowners, granting them the right to impose unlimited fees on the Crimean Tatars living on their land. In 1833, the Russian Minister of the Interior ordered the confiscation of all books and manuscripts from mosque libraries, primary schools, madrasas (educational institutions), private collections, and the homes of ordinary Crimean Tatars. Authorities branded books, ranging from simple accounting records to valuable historical manuscripts, as banned literature and burned them.

Crimean art and architectural monuments were also destroyed, while cities and large towns were renamed. Kezlev became Yevpatoria, Aqmescit became Simferopol, Kefe became Feodosia, Karasubazar became Belogorsk, and the large village of Aqyar became Sevastopol. The Russian conquerors systematically dismantled Crimean Tatar culture, sparking growing anger, which nearly escalated into open rebellion. In 1853, the Crimean War broke out — a struggle for dominance in the Middle East and the Balkans between the Russian Empire and the allied forces of the Ottoman Empire, Great Britain, the French Empire, and the Kingdom of Sardinia. Amid these tensions, the Russian authorities grew increasingly anxious that the Crimean Tatars might side with the allied forces. The Russians devised plans to relocate the peninsula’s inhabitants from the coast to remote provinces of the empire. However, they ran out of time — by September 1854, the allied forces had landed in Yevpatoria, placing the Crimean Tatars at the heart of events that would shape the fate of their homeland.

In this war, Crimean Tatars sided with the Ottoman Empire and its allies. Although the policies of the allied forces did not align with the Crimean Tatars’ interests, the behaviour of the Russians was much worse. Russian paramilitary units ravaged villages and killed civilians. In February 1855, irregular Crimean Tatar units joined the battles near Yevpatoria, successfully pushing back Russian troops. The French command expressed deep respect for the courage shown by the Crimean Tatars on the battlefield.

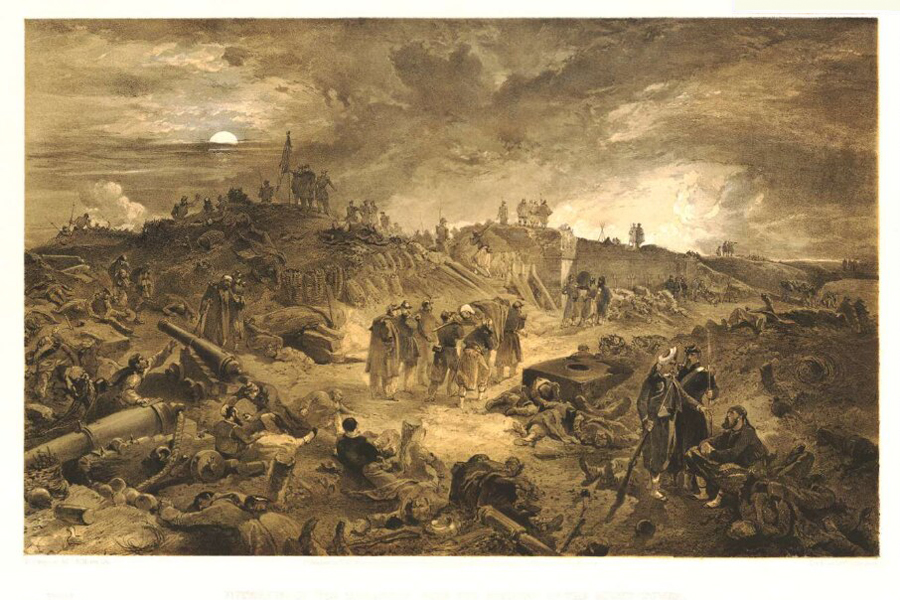

The painting “Malakhov Kurgan with the Ruins of the Round Tower” by William Simpson, 1856. Image source: The British Museum.

Russia lost the Crimean War, and under the terms of the peace treaty, it was forbidden to maintain a navy or arsenals on the Black Sea. However, to the great regret of the Crimean Tatars, Crimea remained part of the Russian Empire. This resulted in their second mass emigration to the Ottoman Empire, which continued until the late 1870s. According to Amet Özenbashli, around 1.8 million Crimean Tatars emigrated to the Ottoman Empire between 1783 and 1920.

However, some Crimean Tatars actively sought to slow this mass migration. Toward the end of the nineteenth century, a group of young Crimean Tatar intellectuals emerged, urging their fellow countrymen to remain on the peninsula or, at the very least, carefully consider their decisions before leaving. Prominent educator, writer, and publisher Ismail bey Gasprinsky spoke out against emigration in his newspaper, Terciman, urging Crimean Tatars not to sell their homes and property cheaply or leave for a foreign country without first gathering information about where they would settle. As a result of the group’s educational initiatives, the wave of emigration began to subside. Their efforts also contributed to a spiritual revival among the Crimean Tatars, the growth of their national consciousness, and changes in Crimea’s socio-political landscape following the Russian Revolution of 1905-1907.

The Russian Revolution of 1905-1907

A series of uprisings against the autocratic rule of tsar Nicholas II, triggered by economic hardship, political repression, and military failures. While it led to some reforms, including the creation of a legislative assembly, the tsar retained significant power, and the unrest set the stage for the 1917 revolutions that ended the tsarist regime.Repressions against Crimean Tatars after the 1917 October Revolution

After the February Revolution in Russia and the overthrow of the monarchy in 1917, Crimean Tatars gained more freedom, as the collapse of the tsarist regime allowed for greater political and cultural expression. In Crimea, the Temporary Crimean Muslim Executive Committee was elected, headed by Noman Çelebicihan. The first political party, Milliy Fırqa (People’s Party in Crimean Tatar), was founded, and the first representative body, the Qurultay (national assembly for addressing important issues), was established. The Qurultay approved the national anthem, coat of arms, and constitution. After the completion of the Qurultay, the Crimean People’s Republic was proclaimed, with Çelebicihan as president.

Participants of the First Qurultay of the Crimean Tatar people, Bakhchysarai, 1917.

However, the hopes of the Crimean Tatars to establish an independent state amid the collapse of the Russian Empire were short-lived. After the fall of the tsarist regime, the empire’s territory became a battleground for competing powers, with the Bolsheviks (a radical communist group led by Vladimir Lenin, that seized power in 1917 and established the Soviet Union – ed.) emerging victorious. In January 1918, just a month after the Qurultay, the Bolshevik forces conquered Crimea and launched the Red Terror on the peninsula. Noman Çelebicihan was arrested and executed.

The Red Terror in Crimea

Massive repressions carried out by Soviet troops in Crimea between 1917 and 1921 were aimed at suppressing political resistance and intimidating the population, resulting in tens of thousands of victims, including officers of the Black Sea Fleet, representatives of the intelligentsia, clergy, as well as ordinary citizens.

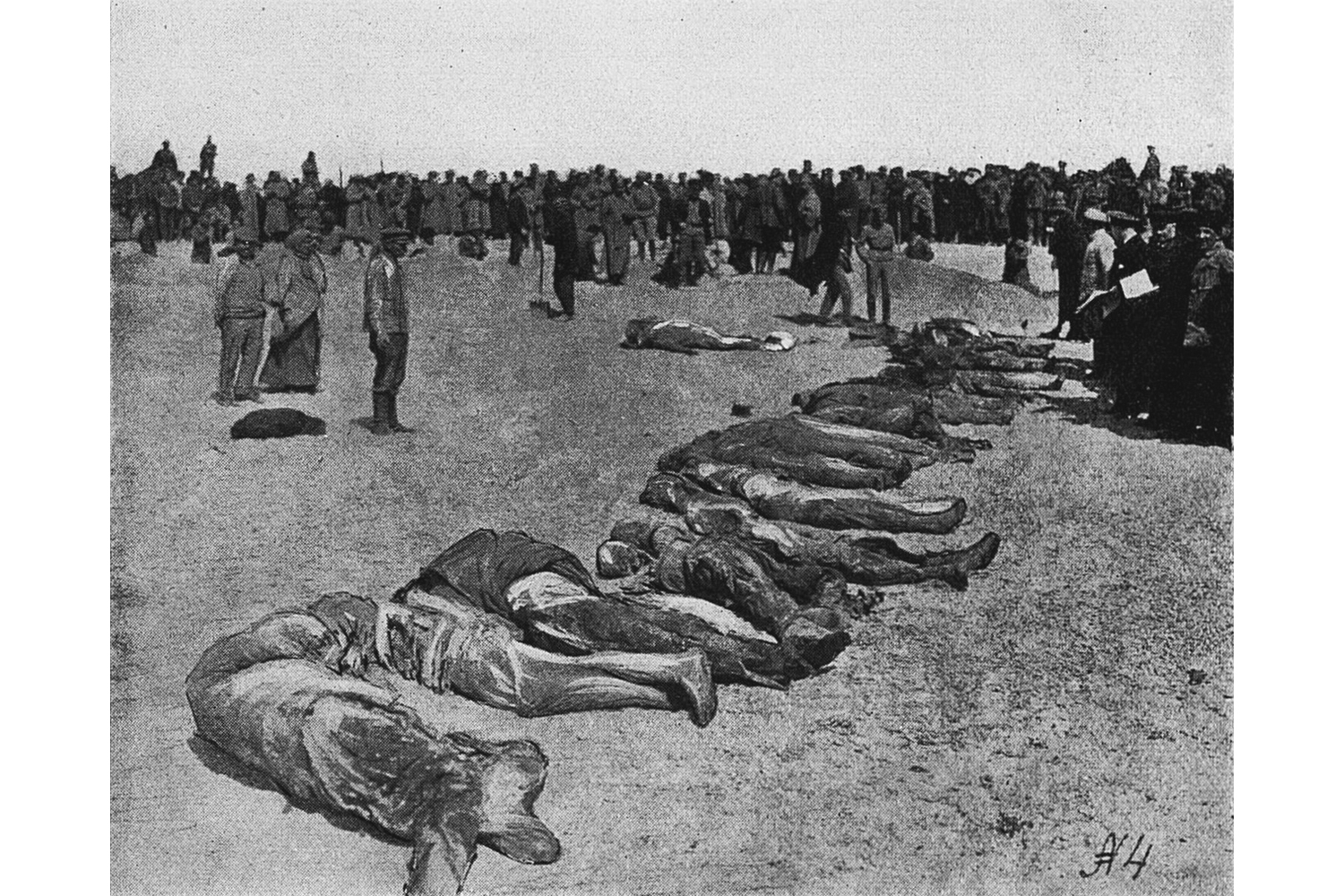

Victims of the Red Terror in Yevpatoria, 1918. Photo source: Essays on the Russian Turmoil by A.I. Denikin, Vol. III.

The Communist victory led to the formation of the USSR. In 1921, the Crimean Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic was established within the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, with Russian and Crimean Tatar as the official languages. However, the brief upsurge in national life after the creation of the republic, which included the opening of national schools, theatres, and newspapers, was followed by Stalin’s 1937 repressions, which affected most Crimean Tatar intellectuals. On 17 April 1938, NKVD (the Soviet secret police responsible for carrying out purges. – ed.) executioners shot dozens of leading Crimean Tatar figures, including public activists, scientists, and political elites. Before their executions, “trials” were held, each lasting no more than 20 minutes. Formally, they were all accused of involvement with the banned Crimean Tatar nationalist party Milliy Fırqa, espionage on behalf of Germany, Britain, and other countries, as well as nationalism. In reality, the executions were meant to eliminate the most influential Crimean Tatars — politicians, teachers, writers, scientists, journalists, and artists — those who shaped public opinion.

The Stalinist repressions

A series of reprisals which took place in the USSR from the 1930s to the 1950s, under the rule of Joseph Stalin. They included the Holodomor (the man-made famine-genocide of Ukrainians), dekulakisation (persecution of landowners and wealthy peasants), the deportation of entire ethnic groups, as well as mass imprisonment and executions of political opponents and cultural elites.The 1944 deportation of Crimean Tatars

The dire conditions of the Crimean Tatars in the newly established USSR were worsened by the 1921-1923 famine, caused by droughts, post-war devastation, forced grain confiscations, and excessive exports of bread outside Ukraine by Soviet Russia. The mass repressions of the 1930s claimed the lives of tens of thousands of Crimean Tatars. Despite all of this, the Soviet government was still intent on carrying out its plan of a “Crimea without Crimean Tatars”. This became possible with the outbreak of the war between the USSR and Germany during World War II. The defence of Crimea at the very start of the war was, famously, a disaster. By the autumn of 1941 – just three months after the Nazi invasion of the USSR – the Germans had completely occupied the peninsula, and the Crimean Tatars were blamed for the failure of the partisan movement. In reality, to cover up their own mistakes, the leaders of the partisan movement in Crimea, Alexei Mokrousov and Serafim Martynov, spread the false claim that the Crimean Tatars had collaborated with the occupiers. In July 1942, they sent a report to Moscow, full of disinformation, stating that “the majority of Crimean Tatars in the highlands and foothill regions followed the Nazis.”

Representatives of the partisan movement in Crimea, around 1943. Photo source: Crimea.Realities.

It’s still unclear who came up with the idea to deport the indigenous people from Crimea, but it is known that preparations for the operation took several years, as shown by the Soviet State Defense Committee’s resolution from 29 May, 1942. On 13 April 1944, NKVD chiefs Lavrentiy Beria and Vsevolod Merkulov signed a top-secret order titled “On measures to cleanse the territory of the Crimean Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic from anti-Soviet elements”, which authorised the deportation of the Crimean Tatars, a plan that had been prepared for several years in advance. This document ordered “to clear the territory of the Crimean Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic of German and Romanian intelligence and counterintelligence spies and agencies, traitors to the motherland and active accomplices, protégés of the Nazi occupiers, and members of anti-Soviet organisations”. To ensure the success of this large-scale operation, NKVD troops were sent to Crimea, led by Fokin, the head of state security in Crimea at the time, and Sergienko, the head of internal affairs in Crimea. They were assisted by their deputies, Kobulov and Serov, who were also key figures in Soviet security services.

Meanwhile, from 11 April to 10 May 1944, the 4th Ukrainian Front successfully liberated the Crimean Peninsula from German occupation during the Crimean Operation. The local population warmly welcomed the Soviet Red Army soldiers. Among the celebrants were many Crimean Tatars who had served on various fronts but had been granted leave to reunite with relatives who had survived the harsh years of Nazi occupation.

The Crimean Tatars celebrated the liberation of the peninsula from the Nazis, unaware of the crime the Soviet government was preparing against them. On 10 May, Beria sent Stalin a draft decision to expel all Crimean Tatars from Crimea “in view of the treasonous actions of the Crimean Tatars against the Soviet people and based on the undesirability of further residence of Crimean Tatars in the borderlands of the Soviet Union”. Simply put, the entire Crimean Tatar people — from newborns to the elderly — were accused of collaboration.

There is still no clear answer as to what personally motivated Stalin in his desire to destroy an entire nation, but certain conclusions can be drawn. It is possible that the decision to remove the Crimean Tatars from their homeland was driven by the whims and self-interest of the Soviet leadership, particularly their desire to militarise the Crimean Peninsula. The only obstacle in their way was the people who had long inhabited the region. It was easier for the Soviets to accuse the entire Crimean Tatar nation of collaborating with the Germans, and leveraging the false 1942 report was a convenient way to justify this. We can see similar tactics today, such as when Russian President Vladimir Putin justified the full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022 by claiming the need to “denazify and demilitarise” the country, accusing the entire nation of neo-Nazism.

The resolution, which became the official justification for the deportation of the Crimean Tatars, was signed on 11 May 1944. It presented detailed “facts” — which were entirely fabricated — accusing the Crimean Tatars of espionage and sabotage behind the Red Army lines.

The deportation was set for the second half of May and was being planned in the usual Kremlin style, with complete secrecy, as the Soviets could not risk any information leaking out.

NKVD troops were deployed to Crimea, and a population census kicked off, with only Crimean Tatars being counted. The addresses of Crimean Tatar families in cities and towns with mixed populations were checked and verified, while military units were sent to villages inhabited solely by Crimean Tatars. Since the fighting of World War II had not yet ended, civilians continued to celebrate the de-occupation and paid little attention to the soldiers in uniform. In fact, there is evidence that local people invited these NKVD officers into their homes and offered them food, as they didn’t understand the difference between military units. To them, Red Army soldiers and NKVD officers appeared the same.

The NKVD (People’s Commissariat for Internal Affairs)

A Soviet government agency responsible for law enforcement, internal security, and secret police activities from the 1930s until 1946, when it was renamed the Ministry of Internal Affairs of the USSR. The NKVD played a central role in carrying out political repression, mass arrests and executions during the Stalinist era, as well as overseeing the labor camps (Gulag).

NKVD officers on vacation in Crimea, 1937. Photo source: Russian propaganda media.

According to the schedule, the deportation was set to begin early in the morning on 18 May. However, in some areas, the operation started on the evening of 17 May. For instance, residents of the Simeiz village were expelled from their homes around midnight, and in some parts of Crimea, deportations began even earlier, at 7 pm.

At 4 a.m. on 18 May, groups of NKVD sergeants, officers, and operatives simultaneously raided Crimean Tatar homes across Crimea, announcing: “In the name of Soviet power! For treason against the Motherland, you are being evicted to other regions of the Soviet Union.” On average, Crimean Tatars were given 15 minutes to pack, but in reality, each NKVD group leader determined the time limit at their own discretion, often giving them less time.

The resolution “On the Crimean Tatars”, which outlined the deportations, allowed “special resettlers” to take up to 500 kg of personal belongings, clothes, household items, utensils, and food. However, NKVD soldiers ignored this provision. Most witnesses to the events of that tragic day reported that they weren’t even allowed to take five kilograms of food with them. Some soldiers confiscated all their food and prevented deportees from taking valuables, utensils, or equipment.

Dilaver Ennanov, who survived the deportation as a child, recalled that day:

“In the evening of 17 May 1944, many trucks arrived in Simferopol, and lots of soldiers appeared in the city. We, young boys, were running around the streets, counting and losing count. If we could have imagined what they were there for… The city had not cancelled the curfew, so my mother and I went to bed early. Suddenly, in the middle of the night, there was a loud knock on the door. I woke up and saw an officer angrily reading something on a piece of paper to my mother, who had just opened the door. Two soldiers were standing in front of her. They were in a hurry and said we had 10 minutes to pack. […] They took us out of the house and into the yard. Our neighbours, also Crimean Tatars, were sitting with their belongings in the rain, surrounded by Soviet troops. We sat with them until dawn. Lorries arrived and we were taken to the outskirts of the city, to the railway station. […] I remember being put in wagon no. 44. There were tears, moans, screams — and the train set off. When we crossed the border and left Crimea, everyone on the train was singing. We were singing and crying as we looked back.”

The painting “Death Train” by Rustem Eminov, 1997. Image source: Tamırlar multimedia platform.

People were terrified and bewildered. They had no idea what they were being accused of or why they were being evicted from their homes. Most older Crimean Tatars didn’t speak Russian at all. Some managed to take valuables with them, while others, in their confusion, only grabbed small trinkets. They were herded into the square, loaded into trucks, and weren’t allowed to leave until dawn. Then, they were taken to the nearest railway station, where cattle cars were waiting for them.

The History of the Crimean Tatars by Valerii Vozgrin includes testimony from Alexei Vesnin, one of the NKVD soldiers who carried out this operation, about the events of that night.

“On 9 May 1944, our unit arrived in Crimea in a direct ‘letter’ train… On the night of 18 May, we were woken up and we walked for several hours across the endless steppe. At 3:30 a.m., we approached the steppe village of Oisul. Only then were we told the purpose of our operation — the eviction of the Tatars. The operation was brilliantly prepared: there were so many brand-new American Fords and Studebakers in the village that they were able to take the entire population to the nearest railway station in one trip. A disabled man with no legs, who had recently returned home from the hospital, was dragged to a car and thrown into the back like a sack of flour… 20 minutes to pack and load — whatever they could carry. A competition was also organised between the groups to see who would finish their section first.”

“Letter” train

A train identified by a letter rather than a number as a sign of its special purpose. Later, this name was assigned to all trains of high importance.Brand-new American Fords and Studebakers, provided to the USSR under the lend-lease programme to fight the Nazis, were used to deport an entire nation.

The Lend-Lease Act

A US law that allowed the United States to supply its allies during World War II with munitions, equipment, food, medical supplies, medicines, and strategic raw materials, including oil products, without payment.Midat Yusunov, another eyewitness of this tragic day, described the initial stage of the deportation:

“People were driven to a cemetery surrounded by machine guns on all sides. Children were taken away from their parents and told that the elder children would be shot and the others would be sent to orphanages. They were held separately for about three hours. During this time, some mothers were driven to madness.”

In some areas, people were actually killed. In the village of Qapsihor, the residents were gathered in a shed, and one of the soldiers decided to see how people would collapse after being hit by machine gun fire. Four people were killed this way.

Witnesses also reported instances of physical abuse. Soldiers would beat people and throw them into trucks. They mocked the Crimean Tatars’ faith, confiscating Qurans and throwing them into toilets.

Crimean Tatar Zera Batalova described the horrific conditions during the deportation and the forced placement in freight cars.

“On 18 May 1944, my mother, Nuriie; her parents, Medzhit and Fatma; her sisters, Biyan and Emina; and her cousin and the cousin’s daughter were taken away. My brother Enver was at war at the time. He only started looking for his relatives in 1946… All of them, except for his mother’s older sister, had ended up in the Urals (a mountain range in Russia, traditionally considered the natural boundary between Europe and Asia. – ed.). My mother was miraculously reunited with her family. But her sister Biyan was sent to Uzbekistan (a post-Soviet country in Central Asia, which was a major destination for the 1944 deportations. – ed.).”

Zera’s mother recalled that their journey to the Urals took at least three weeks. The train only stopped in forested areas, sometimes remaining stationary for days, but they weren’t allowed out of the carriages, so they lost track of time. By the time they finally reached the Urals, they were starving – and were gnawing on tree bark to stay alive. When they learned that potatoes had been planted there the year before, they went searching for frozen potatoes from the previous harvest.

According to testimonies gathered by historian Valerii Vozgrin, severely ill Crimean Tatars, deemed “non-transportable”, were left behind and executed. This took place simultaneously across Crimea. Those who resisted deportation were also shot. The brutality reached a point where entire villages near Simferopol (the administrative centre of Crimea. – ed.), were told they would be killed. People started saying their goodbyes.

On the way to the trains, NKVD soldiers deliberately mixed up families, separating relatives and even neighbours into different railroad cars. Being placed on the trains often meant being torn apart from loved ones, perhaps never to see them again. The trains could be reorganised en route, with carriages detached from one another and brought to different stations.

The deportation was scheduled to last until the end of May, but by 4 p.m. on 20 May, all 67 trains, packed with Crimean Tatars, had already been sent eastward to Central Asia and the Urals.

According to paragraph 2d of the resolution dated 11 May 1944, trains transporting special deportees were meant to provide “hot meals and boiling water every day”, with each train staffed by a doctor and two nurses. In reality, none of these provisions were made. As Vozgrin recounts, up to 200 people were crammed into each railway car, in complete disregard of sanitary standards. Many had to take turns sitting and standing. The wagons, previously used to transport cattle or prisoners of war, were filthy, with straw mixed with horse manure covering the floors. The May 1944 heat made matters worse, as the iron roofs of the wagons became scorching under the relentless sun.

Special deportees (resettlers)

A Soviet legal term, referring to individuals forcibly relocated under Soviet policies, often to remote or inhospitable regions, such as Siberia or Central Asia, as part of political repressions.People succumbed to stress, suffocation, and appalling sanitary conditions, including a lack of water and toilets. The food they had managed to bring from home was quickly exhausted, leaving them to starve. The journey could last anywhere from three weeks to forty days. In some instances, soldiers sold food and water to the Crimean Tatars, but when deaths began occurring, they forbade families from burying their loved ones. At best, the bodies were buried along the railway tracks; at worst, soldiers simply discarded them from the wagons.

When the deportees finally reached their destinations, they were met with hostility rather than assistance. The local population had been warned that “traitors¨ were arriving, and the Crimean Tatars were assigned dugouts, sheds, or barracks that were barely fit for human habitation. The very next day, starving and exhausted from the journey, they were sent to forced labour camps — cotton fields in Uzbekistan and logging sites in the Urals. They were required to report to the commandant’s office daily and were forbidden from leaving under the threat of execution.

Deported Crimean Tatars in a special settlement in the city of Krasnovishersk (now in Perm Krai, Russia), 1948. Photo source: Association of Muslims of Ukraine.

In the months following the deportation, looting became rampant among Soviet soldiers in Crimea. The Russian military, once regarded as the region’s defenders, pillaged homes and shipped “trophy” items back to their families. Today, their descendants carry on this tradition, sending looted goods from the war against Ukraine back to their homes.

Crimean Tatar property was redistributed to immigrants from other parts of the USSR, who began arriving on the peninsula in the autumn of 1944 under the pretext of restoring a peaceful way of life disrupted by the war. During the deportation, Soviet authorities seized 80,350 houses, 34,000 plots of land, around 50,000 head of cattle, as well as vineyards, orchards, equipment, vehicles, and more. All of this was handed over to migrants from the Russian hinterland.

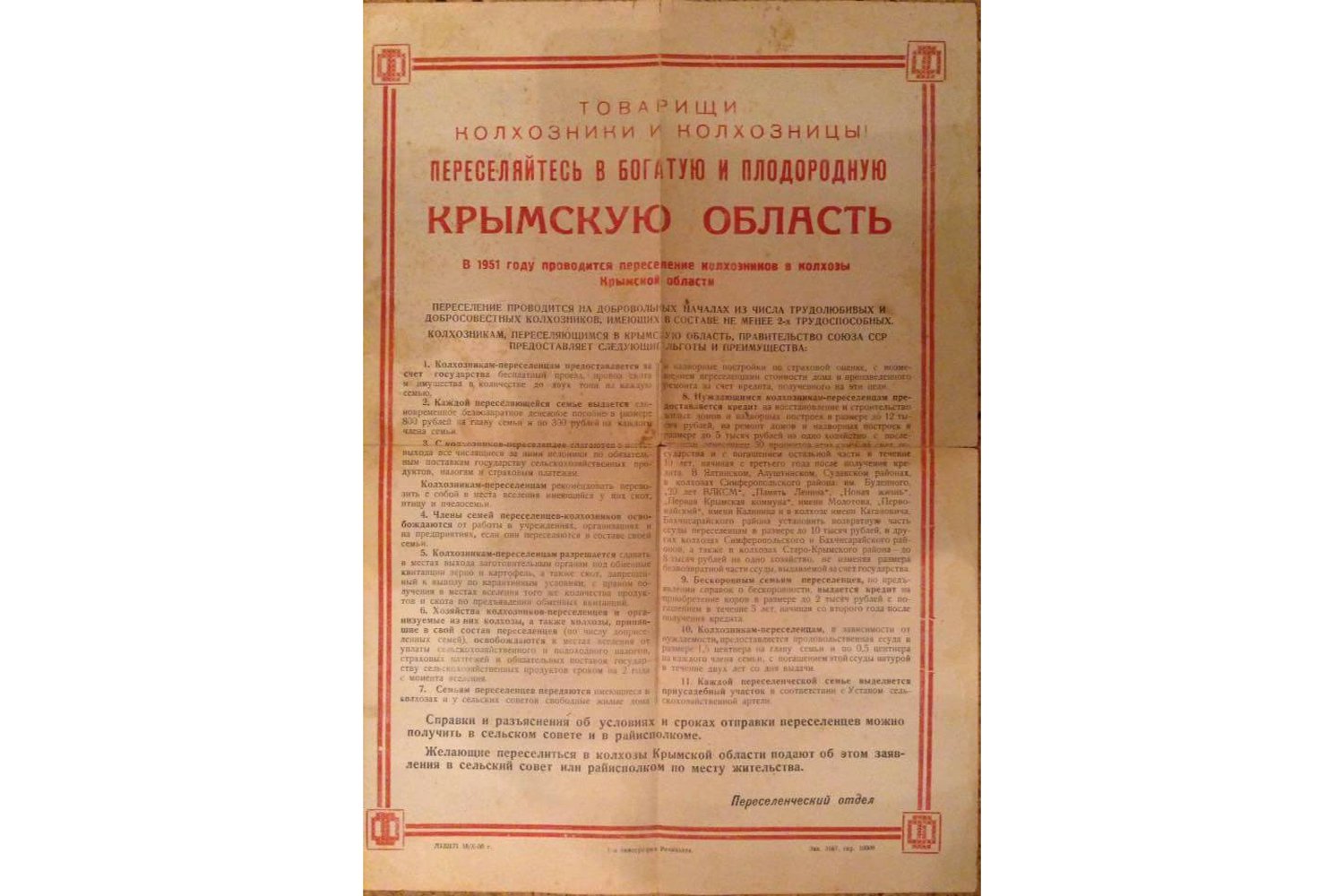

A Soviet propaganda leaflet, 1951. Image source: Wikipedia.

The NKVD leadership reported to Stalin on the success of their special operation to “cleanse Crimea of Crimean Tatar traitors and Hitler’s accomplices”, earning new stars on their shoulder straps as a reward. The names of abandoned villages were all that remained of the peninsula’s indigenous people. Yet life quietly continued on the Arabat Spit, a narrow strip of land running parallel to Crimea’s northeastern coast. Its small population of Crimean Tatars had been overlooked, as the spit was mistakenly considered uninhabited. Historian Valerii Vozgrin recounts how, in September 1945, local authorities stumbled upon this “oversight” by accident. At first, they were bewildered, unsure how to proceed — after all, the deportation had already been officially declared complete. Yet there were several small villages of Crimean Tatars, living peacefully and oblivious to the fate that had befallen their fellow countrymen, who had long since been sent to Central Asia.

This oversight was reported to Bogdan Kobulov, the deputy head of Soviet intelligence and one of the architects of the Crimean Tatar deportation. Knowing that such a mistake could not be ignored, he ordered the Arabat Spit to be cleared within two hours but provided no specific instructions on how to carry it out. One local official devised a “solution”: several dozen Crimean Tatars were rounded up at a marina, locked in the hold of an old barge, and towed to the open sea. Once there, the officials opened the kingstones — valves in the hull designed to let water in — and sealed the upper hatches. Slowly, the barge sank to the bottom of the sea. Convoy boats patrolled the surface for hours afterward to ensure no one managed to escape.

According to Ukraine’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 238,500 Crimean Tatars were deported from Crimea, with 205,900 of them (86.4%) being women and children. The National Movement of Crimean Tatars estimates that the number could have reached as high as 423,100. Those who were seriously ill or resisted were executed on the spot. As a result of the deportation and years of exile, up to 46% of the Crimean Tatars perished, as noted by historian Gulnara Bekirova in her book Half a Century of Resistance: Crimean Tatars from Exile to Return.

Historian Vladlen Maraiev highlights that, despite Soviet propaganda branding the Crimean Tatars as traitors, more than 5,000 Crimean Tatars were drafted into the Red Army before the German-Soviet war, and another 16,000 were mobilised between 1941 and 1945. At least five of them were awarded the title of Hero of the USSR ( the highest honorary title awarded in the Soviet Union. – ed.). Among them was pilot Amet-Khan Sultan, who shot down 30 enemy aircraft and became a two-time Hero of the Soviet Union. Despite their service, these Crimean Tatars were not spared from the Soviet authorities’ plan. Upon their return home as victorious soldiers, they were given just 24 hours to leave for Central Asia.

Some officers, like Amet-Khan Sultan, were not officially deported but were banned from living in Crimea. In 1944, the NKVD accused his brother, Imran, of “aiding the occupiers” and arrested him. They also planned to arrest his mother, but Amet-Khan Sultan intervened to protect her. In the end, his parents were sent to the Krasnodar Territory of the Russian Soviet Republic, where they stayed until the conclusion of World War II.

Amet-Khan Sultan, military pilot and two-time Hero of the Soviet Union. Photo source: Wikipedia.

The deportation of other peoples of Crimea

The Crimean Tatars were the only indigenous people of Crimea deported in 1944, but other non-indigenous groups living on the peninsula also faced deportation. The first were the Crimean Germans – foreign, Mennonite colonists who had lived in Crimea since 1803. By the onset of World War II, more than 51,000 Germans resided in the region. A directive from the Supreme Command Staff on 14 August 1941 ordered the 51st Army to “immediately clear the territory of the peninsula of local Germans and other anti-Soviet elements.”

The deportation of the Crimean Germans began in the same month, August 1941. By the end of the year, 2,233 had been deported. Due to the rapid advance of German troops, a mass deportation was not possible, so men of military age were deported first. According to eyewitnesses, on the day of the deportation, residents of the villages of Neizac and Friedenthal were ordered to gather at a collection point by 4 a.m. with a day’s worth of food and a change of undergarments. A small number of Germans were evicted from the Kerch Peninsula in March 1942, followed by several hundred more in June 1944. The majority of the Crimean Germans were deported to Kazakhstan (then a Soviet republic in Central Asia. – ed.)

Around a thousand Italians lived in Crimea, some of whom were descendants of Italians who had established trading posts on the southern coast in the 14th century. Before the German invasion of the USSR, most resided on the Kerch Peninsula. The first wave of deportations occurred on 28-29 January 1942, when more than 600 Crimean Italians were sent to Kazakhstan by NKVD orders. A second wave took place on 8-10 February, deporting another 70 people. The last remaining Crimean Italians were deported alongside Armenians, Bulgarians, and Greeks in June 1944. They were given only two hours to pack, with a strict limit of 8 kg of luggage per person.

At the beginning of World War II, more than 13 thousand Armenians lived in Crimea. According to the State Defence Committee’s resolution no. 5984 of 2 June 1944, they were also to be deported from the territory of Crimea. As a result of forced evictions on 27-28 June and later, a total of 9,821 people were expelled.

Crimean Bulgarians, like the Crimean Germans, had resided in Crimea since the early nineteenth century as colonists who were generally supportive of the Russian Empire. At the outbreak of World War II, just over 15,000 Bulgarians lived on the peninsula. Their deportation was formalised by the same resolution of 2 June 1944. As a result, a total of 12,628 Crimean Bulgarians were deported.

More than 20,000 Greeks lived in Crimea before 1941, slightly outnumbering the Bulgarians. The forced evictions of the Greeks primarily took place on 27-28 June 1944, with a total of 16,006 deportees. These Greeks were descendants of those who, after 1775, had been relocated to Crimea by Grigory Potemkin, who established a Greek battalion in the imperial army.

The Greek battalion

A military unit formed in the Russian Imperial Army in the late 18th century, made up of Greeks brought to Crimea with the intention of creating a loyal, ethnically distinct group of soldiers and settlers to support Russian rule.Memorandum on the preparation for the deportation of Armenians, Bulgarians, and Greeks, 1944.

Most of these non-indigenous peoples deported from Crimea ended up in Northern Kazakhstan and in the Mari region of the Turkmen Soviet Socialist Republic (remote areas in Central Asia characterised by arid desert landscapes and limited resources. – ed.). Their real estate was confiscated and subsequently occupied by others. Unfortunately, this crime against humanity remains unpunished.

Consequences of the deportation of Crimean Tatars

The deportation marks the darkest chapter in the history of the Crimean Tatars. While the sons of the nation were fighting and dying on the frontlines of World War II, its elderly, women, and children were being transported in cattle carriages to Central Asia and the Urals.

For decades, it was forbidden to speak of the horrific events of 1944. The Crimean Tatar nation was essentially erased for 80 years, with the Soviet Union even banning the use of the word “Crimean”, referring to them simply as “Tatars”. As a result, the Crimean Tatars were intentionally lumped together with other numerous Tatar groups in the USSR, such as the Kazan, Qasim, Bashkir, and Siberian Tatars. Despite this, the Crimean Tatars never forgot their roots.

In 1945, a decree by the Supreme Soviet of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, which Crimea was part of at the time, ordered the renaming of 1,062 Crimean settlements, the demolition of historical monuments, the destruction of over 1,500 libraries and private book collections, the obliteration of cemeteries and tombstones inscribed in the Crimean Tatar language, and the closure of 861 Crimean Tatar schools, museums, research institutes, and cultural centres. In addition to losing their homeland, the Crimean Tatars were scattered across various regions of the USSR, effectively condemning their nation to extinction. This is why the deportation of the Crimean Tatars in May 1944 is considered genocide.

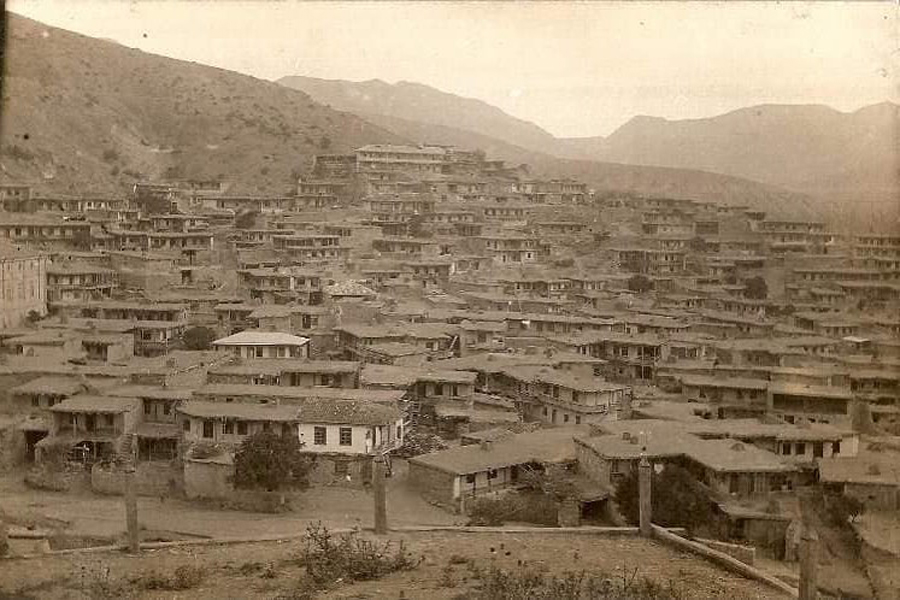

The village of Uskut after the deportation of the Crimean Tatars, 1945. Photo source: Wikipedia.

The consequences of the deportation were also devastating for Crimea itself. With the sudden mass deportation of the indigenous population, who had deep ties to the land, a new, artificially created society was introduced to replace them. Immediately following the deportation of the Crimean Tatars in 1944, the governing body of the Communist Party in the Soviet Union instructed the Soviet authorities on the peninsula to “create a new Crimea, with its Russian way of life.” To achieve this, they aimed to demolish the jewel of Crimean history and culture — the Khan’s Palace in Bakhchysarai, which symbolised the former statehood of the Crimean Tatars. Fortunately, the palace was miraculously saved by its then-director, Maria Kustova.

The Khan’s Palace

A historic residence of the rulers of the Crimean Khanate, serving as a political and cultural centre for the Crimean Tatars from its establishment in the 16th century until Crimea’s annexation by the Russian Empire in the late 18th century.In the summer of 1944, the secret Decree no. 6372 of the State Commissariat of Defence was already in place to relocate thousands of peasants — and even some urban residents — from various regions of the USSR. The incentivised and forced resettlement of peasants to Crimea began, with large groups of settlers directed towards previously densely populated areas, in particular:

– Yalta (1000 families from the Rostov region of modern Russia);

– Alushta (2500 families from the Krasnodar Territory of modern Russia);

– Sudak (2500 families from the Stavropol and Krasnodar territories of modern Russia);

– Karasubazar (2700 families from the Tambov and Kursk regions of modern Russia);

– Staryi Krym (1300 families from the Rostov and Kursk regions of modern Russia);

– Balaklava (2000 families from the Voronezh region of modern Russia);

– Bakhchysarai (2000 families from the Oryol and Bryansk regions of modern Russia).

Crimean Tatars in a special settlement in the town of Krasnovishersk (now Perm Krai, Russia), 1944. Photo source: Ukrainian Institute of National Memory.

The new settlers were largely disconnected from the region’s historical context, which was one of the Soviet government’s hidden objectives — to erase the historical memory of these areas. Post-war immigrants began settling in traditionally Crimean Tatar regions, where many homes were left vacant. “They all came with a strong desire to restore Crimea’s agriculture and settle permanently in this fertile southern region!” wrote Soviet “journalists” of that time. In reality, however, the “new Crimean residents” faced unfamiliar working conditions and an entirely new climate.

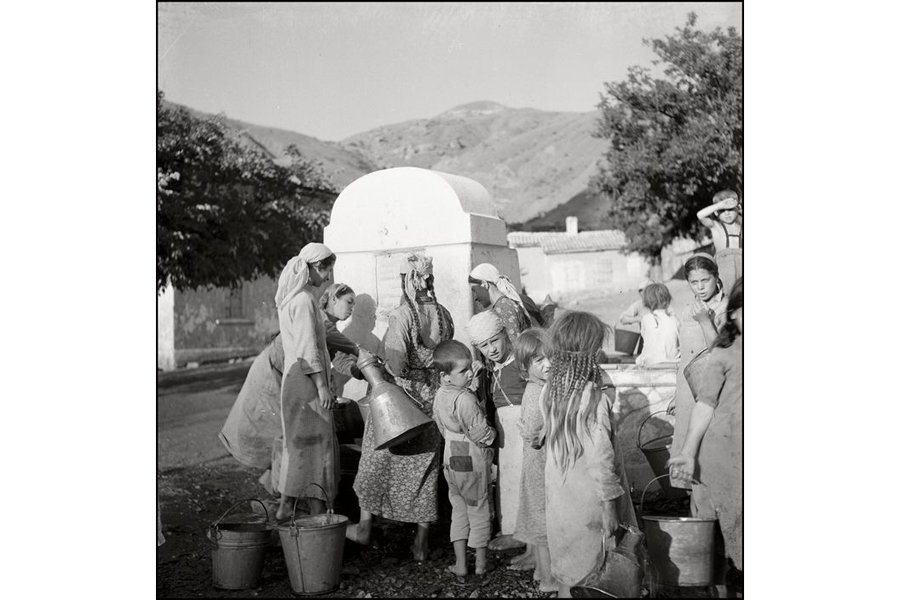

In the first few years, around 170 collective farms were established. However, rather than restoring Crimea, the settlers only caused further harm. They devastated the natural and cultural landscape, chopping down fruit trees and vineyards for firewood. Their attempts to manage the traditional Crimean Tatar water supply system were even more disastrous. Lacking the necessary knowledge, they failed to maintain or properly clean it. As a result, of the hundreds of small fountains once found in every town and village, only a few remained, while ancient wells and springs in the foothills and mountains were left polluted.

One of the most striking examples of the water supply system destruction occurred in the Crimean village of Dehirmenkoi, which was renamed Zaprudne following the 1944 deportations. This large, ancient settlement was once rich in water, with 165 well-maintained springs, each lined with stone and bearing its own name. Dehirmenkoi provided water to the Artek children’s camp (a famous international children’s camp and a symbol of the Soviet youth culture. – ed.) as well as to the surrounding settlements. However, after 1944, almost all of these springs were destroyed by the new residents, with only one surviving.

Crimean Tatars near a fountain, 1943. Photo: Herbert List (Magnum Photos).

Another well-known spring in Inkerman was famous for its healing waters. Once the home of an aziz, known as Inkerman-baba, it was often visited by pilgrims. After the deportation of the Crimean Tatars, the aziz’s grave was demolished during the construction of a local quarry. The water supply to the healing spring was disrupted, and its waters were diverted into the quarry, disappearing forever.

Muslim cemeteries were the next to be destroyed. The settlers used the rectangular stone headstones to construct houses, sheds, and fences. Some tombstones, inscribed with Arabic script, were even repurposed to build sidewalks.

Crimean aziz

A holy site associated with the activities of Islamic righteous figures (sheikhs), which could be a grave, spring, tree, stone, cave, or another natural or man-made object.

Crimean Tatar cemetery in Bakhchysarai. Photo source: Holos Krymu newspaper.

A little later, new immigrants — often referred to as the Soviet elite — arrived in Crimea. Retired NKVD officers, party workers, and many others were granted land plots for life, and new cottages and recreational areas were built for them. It was these settlers and their descendants who would later identify as “indigenous Crimean residents” and advocate for their interests in Moscow after Crimea officially came under the jurisdiction of Kyiv in 1954. For the most part, they were also the ones who opposed the return of Crimean Tatars to their historic homeland.

First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) Central Committee, Nikita Khrushchev, in Crimea, 1963. Photo source: Getty Images.

After the deportation, the population of Crimea was deliberately replaced. However, the settlers were unable to restore the region’s economy; in fact, they largely destroyed what little remained. By the 1950s, it was clear that urgent action was needed, as Crimea was gradually becoming a waterless desert. The only solution was to build the North Crimean Canal and bring farmers from the southern regions of Ukraine, who were skilled in cultivating black soil, to the peninsula. After the transfer of the peninsula to Soviet Ukraine in 1954, Crimea’s economic situation began to improve.

The North Crimean Canal

A major waterway constructed in the 1960s to supply water from the Dnipro River in Ukraine to arid regions of Crimea and southern Ukraine. It was a key source of irrigation and drinking water for Crimea until 2014.

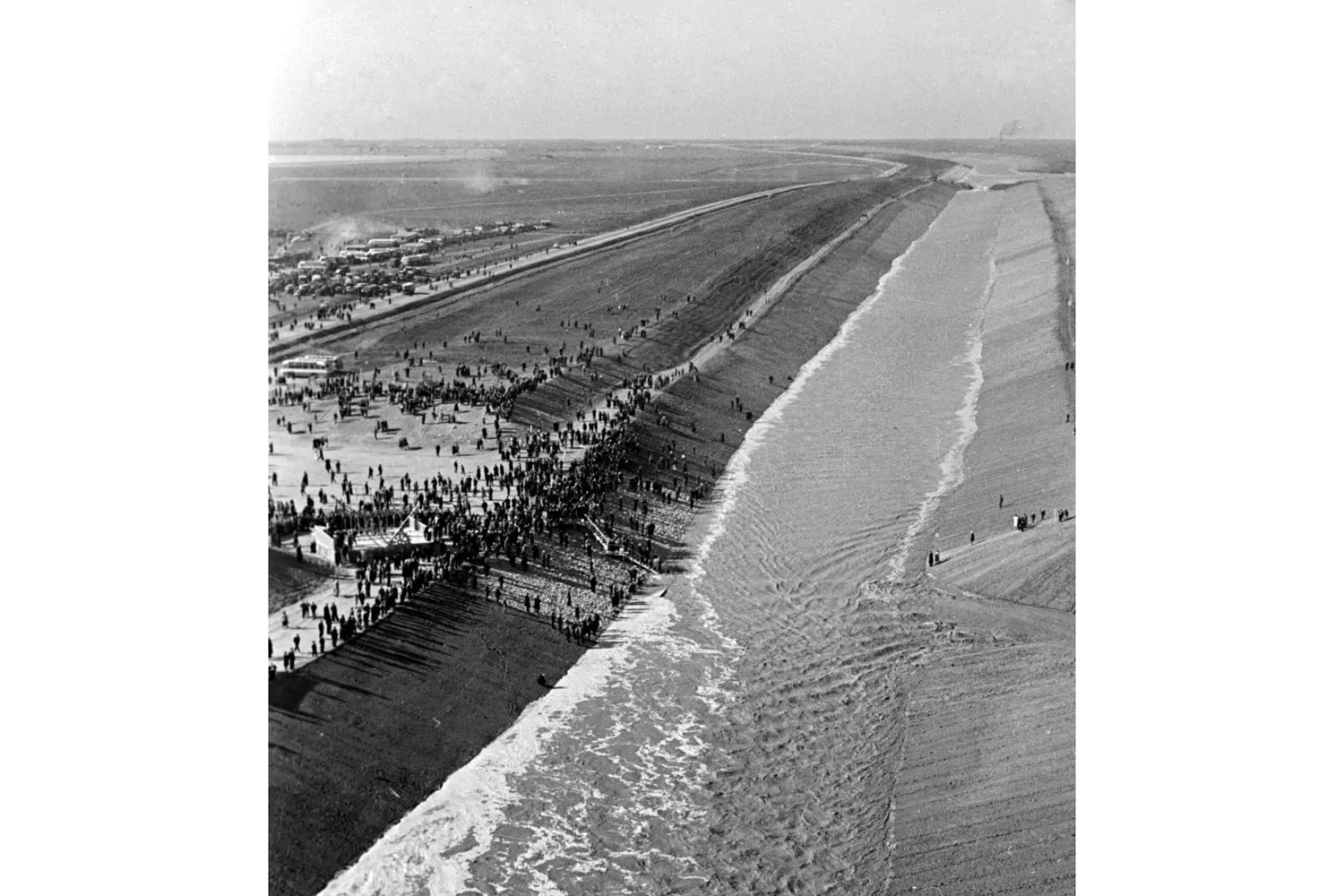

Construction of the North Crimean Canal. Photo source: Soviet propaganda media.

Ten years after the deportation, Crimean Tatars started persistently seeking the restoration of their rights. The national movement of Crimean Tatars for the return to their homeland was born in this period. In 1956, they were removed from the register of special settlers and released from administrative supervision. However, this did not absolve them of the false charges nor grant them the right to return to Crimea. As a result, an active struggle for the restoration of their rights began.

In 1967, Soviet authorities issued a decree that partially annulled the deportation of Crimean Tatars, but it did not actually allow them to return to their homeland. In response, Crimean Tatars launched mass protests, which were brutally suppressed. On 17 May 1968, around 800 Crimean Tatars from different regions gathered in Moscow for a demonstration to mark the anniversary of the deportation. Like other protests, it ended in violence, with participants beaten and arrested by KGB officers. In addition to mass protests, Crimean Tatars submitted petitions and appeals to the country’s leadership, collected signatures for protest letters, and highlighted the issues of the deportation in self-published works.

Between 1967 and 1970, despite the evictions and trials for violating the passport regime, 3,026 Crimean Tatars resettled in Crimea, some of whom had been exiled multiple times. In June 1978, Crimean Tatar activist Musa Mamut set himself on fire in protest of the persecution of Crimean Tatars in Crimea. His act of self-immolation became a symbol of the Crimean Tatar movement for the return to their homeland. In the late 1970s and early 1980s, several key figures of the movement, including Mustafa Dzhemilev, Reshat Dzhemilev, Rollan Kadiiev, Eldar Shabanov, Yurii Osmanov, and others, were arrested and sentenced.

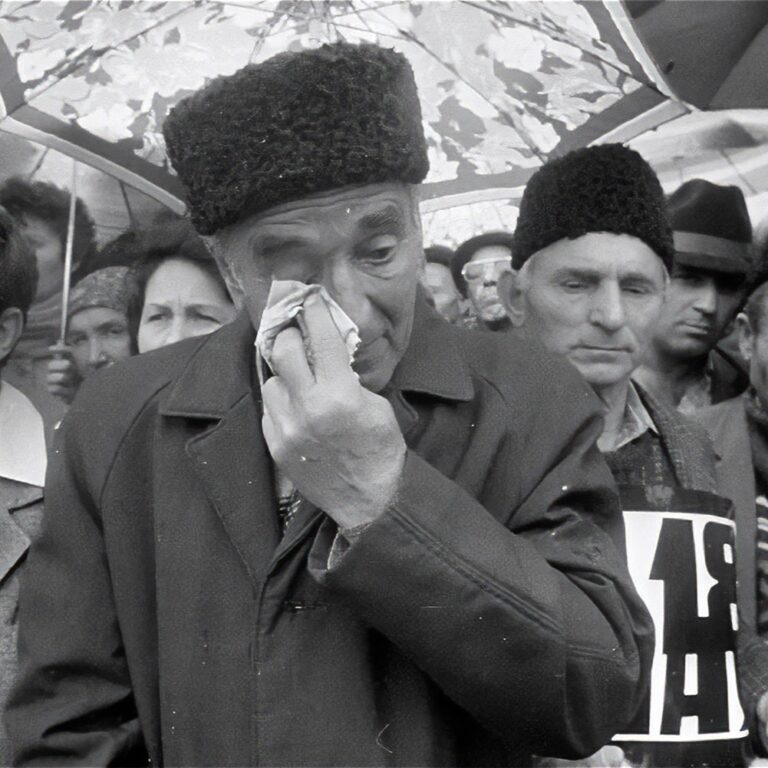

A Crimean Tatar rally in Bekabad, Uzbekistan, 1988. Photo source: Crimea.Realities.

In the 1980s, the Crimean Tatar movement re-entered the political arena. In 1983, the Musa Mamut Initiative Group of Crimean Tatars published a newsletter in Crimea. It was only in 1989 – during the liberalisation of the Soviet regimes known as perestroika – that the Supreme Soviet of the USSR condemned the deportation and recognised it as illegal and criminal.

The Crimean Tatars needed a homeland, a native language, and material and spiritual culture. The national movement of Crimean Tatars chose a non-violent means of struggle and broke through the Soviet system, eventually succeeding in returning its people home. Despite the fact that it was a difficult journey, most Crimean Tatars began to return to Crimea en masse from their places of exile in the early 1990s.

Right after beginning to return to their Crimean homeland, Crimean Tatars started restoring their right to self-determination by launching the second Qurultay. It began its work in Simferopol on 26 June 1991, shortly before Ukraine proclaimed its independence from the USSR. The Qurultay adopted the Declaration of National Sovereignty of the Crimean Tatar People and elected the Mejlis, the highest representative body of the Crimean Tatars, through secret ballot. It was at this point that the Crimean Tatars decided to be part of an independent Ukraine. Unfortunately, in 2014, just over 20 years later, Ukrainian Crimea suffered a terrible tragedy — another Russian occupation. Today, we are witnessing history repeat itself, as Russia continues to use the same methods.

The Mejlis

Arabic: مجلس- Majālis, literally - place of assembly. The Mejlis is a legislative and representative body, akin to a parliament, that serves as the highest decision-making authority for the Crimean Tatar people.

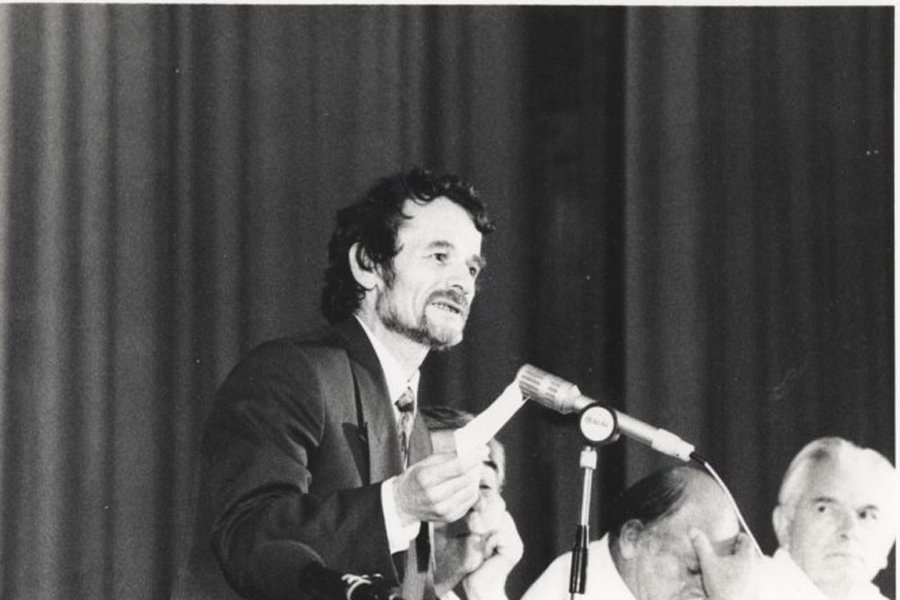

Mustafa Dzhemilev during the Second Qurultay of the Crimean Tatar people, 1991. Photo source: Crimea.Realities.

Russian crimes against Crimean Tatars after the 2014 occupation of Crimea

The Russian occupation of Crimea in 2014 marked the beginning of a new chapter of oppression in the history of Ukraine and the Crimean Tatars. Repressions against those who openly resisted the invaders began in the very first days of the occupation.

The occupying authorities moved swiftly to stifle the distinctive culture and identity of the Crimean Tatars. All NGOs, media outlets, and religious associations were required to re-register. Most refused to comply and were forcibly shut down. ATR, the first and only Crimean Tatar TV channel, was forced to relocate to mainland Ukraine and continue broadcasting from Kyiv.

The Russian authorities gradually pushed the Crimean Tatar language out of the education system and public life. The Kremlin has declared the Mejlis an “extremist organisation” and banned it, forcing its leaders to flee Crimea and “nationalising” its building.

Following the 2014 occupation, between 60,000 and 100,000 people were forced to leave Crimea because they either refused to accept the new conditions or were in danger. At least 30,000 of them were Crimean Tatars. Those who remained and resisted the concept of “Russian Crimea” continued to face repression.

Arrests of Crimean Tatars in temporarily occupied Crimea. Photo source: Russian propaganda media.

According to the Crimean Human Rights Group, the first victim of the Russian terror was Crimean Tatar Reshat Ametov. In March 2014, while holding a solitary picket sign in Simferopol, he was detained by individuals identifying themselves as the “self-defence of Crimea”. He was later found dead, showing signs of torture. Following Reshat’s murder, abductions, arrests, and searches of other activists became relentless.

The “self-defence of Crimea”

Was a Russian-backed paramilitary group which aided the Russian occupation of Crimea by intimidating, detaining, and torturing those who opposed the occupation under the guise of maintaining order during protests.In May 2014, Crimean Tatar activists Timur Shaimardanov and Seyran Zinedinov were reported missing. Later that year, in September, the son of Crimean Tatar human rights activist Islyam Dzhepparov and his nephew Dzhevdet Islyamov also disappeared. In May 2016, Erwin Ibragimov, a public activist and member of the World Congress of Crimean Tatars, went missing as well.

In 2016, the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe (PACE) adopted a resolution stating that the cumulative effect of the oppression by Russian occupation authorities posed a threat to the very existence of the Crimean Tatars as an ethnic, cultural, and religious community.

Criminal proceedings were initiated against most of the detained Crimean Tatars, primarily for alleged membership in the Hizb ut-Tahrir (an international pan-Islamic organisation banned in Russia. – ed.) and sometimes for suspected involvement in the Noman Çelebicihan Battalion. In some cases, even relatives and neighbours of the accused were persecuted. Later, members of Crimean Solidarity – an association of activists and relatives of accused and convicted Crimean Tatars – also became targets of persecution.

The Noman Çelebicihan Battalion

Is a volunteer paramilitary unit which was formed in 2016 in response to the Russian occupation of Crimea and included to the Ukrainian Armed Forces during the full-scale Russian invasion.As of February 2025, many Crimean Tatars remain imprisoned in Russian jails, including activists Aasan and Aziz Akhtemov. In June 2024, Crimean Tatar politician, lecturer, political scientist, and journalist Nariman Dzhelyal was successfully freed from Russian captivity. From the very beginning of Crimea’s occupation, he stayed and fought for the peninsula’s freedom, fully aware that the occupying authorities would never forgive his pro-Ukrainian stance. Yet, he refused to leave Crimea and continued to support those who had become hostages of the occupiers.

After attending the Crimea Platform summit in Kyiv in September 2021, his home was raided early in the morning, and he was taken away to an unknown location. It was later revealed that he and the Akhtemov brothers had been absurdly accused of sabotaging a gas pipeline in the village of Perevalne, near Simferopol. Of course, they had nothing to do with the explosion, but the occupiers needed a high-profile case to justify their repression.

Crimea Platform

An international diplomatic initiative that brings together world leaders, policymakers, and experts to discuss strategies for the de-occupation of Crimea, address human rights violations, and strengthen international pressure on Russia.Since the outbreak of full-scale war on 24 February 2022, repression and terror in Crimea have escalated, quickly extending to newly occupied territories. The Russian Federation passed a law imposing sentences of up to 15 years in prison for spreading “false information about the actions of the Russian military”, making dissent in Crimea even more perilous. According to the Crimean Tatar Resource Centre, between February and September 2022 alone, Russian security forces carried out 25 searches, detained 108 people, and conducted 124 interrogations in Crimea. In just the first nine months of 2022, 138 people were arrested on the peninsula, 104 of whom were Crimean Tatars opposing the Russian occupation and military aggression.

Illegal searches at the mosque in the city of Stary Krym, 2024. Photo source: Crimean Solidarity.

With the start of the full-scale war and the occupation of southern territories, where Crimean Tatar communities also live, the persecution of Crimean Tatars expanded beyond the peninsula. Despite this, Crimea continues to actively resist the occupiers.

One of the key aspects of Russia’s repressive policy towards the Crimean Tatars is forced mobilisation. Tamila Tasheva, the Ukrainian President’s representative in the Autonomous Republic of Crimea (until December 2024 – ed.), stated that, in the first few days of mobilisation alone, Crimean Tatars received around 1,500 summonses from Russian authorities. This has triggered another wave of Crimean Tatars fleeing the peninsula. Mobilisation in occupied territories is a serious breach of the Fourth Geneva Convention and, according to international law, amounts to a war crime.

A representative of the Russian Orthodox Church blesses those drafted in Crimea’s Sevastopol, September 2022. Photo source: Reuters.

The occupation authorities in Crimea show a blatant disregard for Crimean Tatar cultural heritage, identity, and memorial sites.

The occupiers desecrate and destroy memorial sites dedicated to Crimean Tatars, including monuments and tombstones in cemeteries, plaques commemorating Crimean Tatars who perished during World War II, and various monuments bearing Crimean Tatar symbols. In the first six years of occupation, 23 such incidents were recorded. Acts of vandalism tend to spike around significant dates commemorating the 1944 deportation of Crimean Tatars. Activists try to document and bring attention of the occupational law enforcement to the damage to these cultural landmarks, but their efforts have thus far been futile.

“Throughout the occupation, the Russian administration has dismantled established economic ties, created its own judicial and law enforcement systems, imposed Russian standards in education and social welfare, and seized private property and land from Ukrainian citizens under various pretexts,” Tamila Tasheva says.

Crimes against the indigenous people of Crimea continue to this day. The Russian authorities are using the same methods of terror and destruction they employed centuries ago in attempts to erase nations. Specifically, since 2014, Russia has resumed its policy of deportation against Ukrainians in the occupied territories.

Present-day deportations of Ukrainians by Russians

According to human rights activist Onysiia Syniuk, the Russians had planned the forced deportation of Ukrainians even before launching the full-scale invasion.

“As of 20 February 2022, the government of the Rostov region of Russia reported that 188 permanent accommodation centres were being prepared for ‘Donbas residents’. As of October 2022, 807 such centres were operating in Russia.”

Syniuk emphasised that the Russians had no justification for deporting people and described how they subjected Ukrainian citizens to inhumane treatment. They forcibly took Ukrainians to Russia without telling them where they were going, denied them tickets to other countries, and deprived them of food and water for several days. Russian authorities also held them in appalling conditions and applied psychological pressure.

This is how 19-year-old Andrii and his mother were deported from Mariupol. First, the Russians took them to temporarily occupied territory where they held them in a filtration camp for several days, checked their phones, and confiscated their documents. The family had no choice but to stay there or go to Russia. Andrii decided to go to Russia with his mother and then escape to Estonia. However, their captors transported them, along with 60 other people, to Taganrog (a city in the south of Russia located 2,000 km from the Estonian border. – ed.) and forced them to wait three months to receive Russian passports. Thanks to volunteers, Andrii was able to get to Norway, but his mother refused to go, saying she couldn’t bear it mentally.

Temporary camp for deported Ukrainians in the Russian city of Taganrog. Source: Getty Images.

Another story is that of Yuliia and her two sons, 11-year-old Matvii and 5-year-old Ivan, who were deported from Rubizhne. They had been hiding in a basement to escape Russian shelling, as volunteers were unable to evacuate them due to the fighting in the city. When Russian forces occupied Rubizhne, a Kadyrovite (the informal name for paramilitary groups loyal to Ramzan Kadyrov, the head of the Chechen Republic in Russia – ed.) found the family and ordered them to pack their belongings in minutes, much like the NKVD officers had done to the Crimean Tatars in 1944. Yuliia and her sons were taken to a checkpoint between Ukraine and Russia, where they were forced to walk seven kilometres to the border and interrogated for several hours. They were then deported to the Rostov region and later to Saint Petersburg, a journey that lasted 36 hours. During another interrogation, Yuliia said she would stay with relatives in the city to prevent further deportation. After enduring several filtration camps and interrogations, the family finally managed to reach Estonia.

The Russians have even deported people with disabilities. Among them is 35-year-old Bohdan, who uses a wheelchair. He had been living with 200 seniors and 40 other individuals with disabilities at a facility in Kakhovka, a city in southern Ukraine, which was occupied by Russian forces in 2022. When the Russians occupied the city, the staff continued their work, but later, the invaders “appointed” new employees who immediately decided to deport the residents. First, they were taken to Dzhankoy in Crimea, then to Voronezh, Russia, where they were dispersed across various institutions. The Russians held Bohdan in appalling conditions, cut off his internet and cellphone service, and attempted to force him to change his citizenship to Russian, a choice he rejected. Bohdan endured repeated torture simply for being Ukrainian. Fortunately, he managed to contact volunteers who helped him navigate the difficult journey to the Russian border and eventually reach Norway, where he now resides.

During the Soviet era, the Kremlin carried out over 100 deportations aimed at destroying entire peoples and altering the ethnic composition of regions. Most of the deported individuals were never allowed to return home, and even if their descendants managed to do so, they returned into societies that had been artificially reshaped by Soviet authorities. Russia is now attempting to replicate this strategy in the occupied territories of Ukraine. Only Ukraine’s victory and the defeat of the aggressor will allow the deported Ukrainians to return home and the Crimean Tatars to restore their lives in Crimea.