Ukraine’s centuries-old struggle against Russian colonisation stretches back to the 17th century and still rages on. In this article, Kyrylo Cyril Kutcher from Te Kunenga ki Pūrehuroa Massey University of New Zealand draws parallels between the current Russian invasion and the one from 1918–21, revealing how history sheds light on today’s diplomatic deadlocks. He also evaluates proposed solutions to reduce or end the violence, explains the likely consequences of a ceasefire, and examines public sentiment through surveys and personal stories from Ukraine.

The Ukrainian nation today is immersed in a struggle for its survival and future much as it was a century ago during a short-lived independence in 1918-1921 under the Ukrainian People’s Republic (UPR). Ukrainians yet again stand against the imperial ambitions of the violent Russian nationalism manifesting through the brutal invasion of Ukraine. Realisation that the 2014-present Russo-Ukrainian war is not the first and learning from mistakes and outcomes of the previous one are imperative preconditions for analysing or suggesting resolution to the one ongoing right now.

Equipped with historical perspective, questions such as “Who is involved in the current war? What are their war aims? And what about peace?” must be answered. The primary parties of this clash are the states and people of Ukraine and Russia, with international actors either picking sides, suggesting ceasefires, or distancing themselves from the war. While Moscow seeks imperial control over Ukraine, Ukrainians seek freedom from external violence and the preservation of their state’s sovereignty and territorial integrity. In other words, the present Russo-Ukrainian armed conflict is a return to an old colonial war of conquest. Most suggested diplomatic resolutions promote peace through a ceasefire, indulging violent conquest over international law.

A sniper with a rifle. Slobozhanshchyna. February 2024. Photo by Herman Krieger.

This article demonstrates that the ongoing Russian war against Ukraine is a historically coherent attempt to obliterate the Ukrainian state, appropriate its resources, and destroy the Ukrainian ethnos. It suggests that a confederation or alliance of determined nations could re-establish and effectively protect peace in Ukraine and the region from external violence.

Historical Context of the Russo-Ukrainian War

Moscow’s systematic efforts to subjugate Ukraine date back to the 1654 Pereiaslav agreement between Bohdan Khmelnytsky, the Hetman (a leader) of the Ukrainian Kozaks, and the Muscovites. Historian Timothy Snyder, in his book The Reconstruction of Nations: Poland, Ukraine, Lithuania, Belarus, explains that Ukrainians saw the agreement as a circumstantial military alliance. Meanwhile, the Muscovites treated it as an eternal pledge of allegiance and cession of any independence by Ukrainians to the Tsar in Moscow. Russia, originally named Muscovy until 1721, exploited security vulnerabilities of the Ukrainian Kozak Hetmanate, a de-facto sovereign proto-state, and gradually colonised most of the Ukrainian lands and heritage between the 17th and 19th centuries.

In The Gates of Europe: The History of Ukraine and The Russo-Ukrainian War: The Return of History, American-Ukrainian historian Serhii Plokhy analyses key historical events, including the Bolshevik occupation of Ukraine in 1921 and the country’s regained independence in 1991. In 1918, despite the proclamation of the independent Ukrainian People’s Republic, post-imperial Russia invaded and, by 1921, eventually overpowered the de-jure independent country, transforming it into the republic of the Soviet Union. As Ukraine regained its independence in 1991, Moscow ensured that Kyiv was stripped of the world’s third-largest nuclear deterrence arsenal in exchange for paper security assurances of the 1994 Budapest Memorandum. Over the following years, Russia made relentless efforts to steer Ukraine back into the Russian World. In 2014, it invaded Crimea and the eastern regions and, in 2022, launched a full-scale invasion of the country.

The "Russian World"

is a Russian ideology promoting Russia's cultural and political dominance over Russian-speaking communities globally, often to justify its influence or aggression.

U.S. President Clinton, Russian President Yeltsin, and Ukrainian President Kravchuk after signing the Trilateral Statement in Moscow on 14 January 1994, source: William J. Clinton Presidential Library

Almost precisely a hundred years apart, after being ousted from Kyiv at the will of the Ukrainian people in 1917 and 2014, Moscow resorted to constructing and legitimising a politically motivated alternative reality backed by invading troops. As Serhii Plokhy explains, the Bolsheviks lost the vote of the national delegates in Kyiv in December 1917 to supporters of the Central Rada, the parliament of the Ukrainian People’s Republic. Disappointed with the results, the Russians immediately set up an alternative congress of delegates in Kharkiv, a city in the east of Ukraine, where they declared the creation of a virtual state, the Ukrainian People’s Republic of Soviets or Soviet Ukraine. In the name of that sham entity, Russia invaded Ukraine in January 1918.

The Bolsheviks

A communist political faction led by Lenin that overthrew the Russian transitional liberal government in the October 1917 coup.Something similar happened in February 2014 after the Ukraine’s Kremlin-controlled President, Viktor Yanukovych, fled to Russia under pressure from the prolonged mass protests known as the Maidan or the Revolution of Dignity. Within days, the Russian troops from the leased naval base in Crimea dispersed across the peninsula. Shortly after, an illegal referendum was held at gunpoint, and Crimea was occupied by Moscow in March 2014. By April, the special forces and other military formations from Russia infiltrated Donbas, set up another referendum in the controlled territories and declared the creation of the so-called Donetsk and Luhansk People’s Republics. On the pretext of protecting people in those puppet states, Moscow launched the full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022.

Russians limit their appetite for violence and conquest only when confronted with a vigorous military rebuff. According to Serhii Plokhy, Ukraine’s lack of a standing army in 1917 made it vulnerable to Russian invasion in early 1918, forcing it to seek German-Austrian support. On 9 February, the Ukrainian People’s Republic signed the Brest-Litovsk agreement with Germany, Austria-Hungary, Ottoman Empire, and Bulgaria, securing formal international recognition of independence. This was a desperate move under the imminent threat of a Bolshevik attack, especially after the Entente refused to recognise Ukraine’s independence. Although Germany compelled the Bolsheviks to acknowledge the UPR’s sovereignty on 3 March 1918, it proved futile. By 1919, Russia had reclaimed most of Ukraine through propaganda and force, while the Ukrainian government was left without external support.

Similarly, by puppeteering the President of Ukraine Viktor Yanukovych since 2010, Moscow ensured that the Armed Forces of Ukraine were too weak to prevent its covert invasion in early 2014. However, reforms in the military-industrial and defence sectors after 2014 enabled the Ukrainian military to fight against the more resourceful enemy in 2022 and liberate territories previously occupied by the Russian invaders. Failing to fully conquer territories, Moscow resorted to a political conquest on paper by declaring annexation of four of Ukraine’s southeastern regions (Kherson, Zaporizhzhia, Donetsk and Luhansk) in September 2022. Meanwhile, Ukrainians performed many successful military operations on land, air and sea domains, preventing Russians from freely operating manned aircrafts in Ukrainian skies and ships in the Black Sea, and taking control over part of Russia’s Kursk region in August 2024.

Reworking of ammunition at the engineering center of the Achilles Battalion, 92nd Brigade. February 2024. Photo by Karyna Piliuhina

In Ukraine’s defensive efforts, ally support often defines its victory or defeat. After German-Austrian troops left Ukraine at the end of the First World War, Russia invaded again in 1919. In 1920, the Ukrainian leadership found only Poland interested in the existence of a buffer state between itself and Russia. Poland was willing to form a military-economic alliance against Moscow in exchange for Ukraine ceding its western territories. That alliance helped to stop Russian westward offensives, and eventually contributed to the Polish victory over Soviet Russia. Unfortunately, with the nationalists dominating Polish domestic politics and diplomacy, Warsaw abandoned its alliance with the Ukrainian People’s Republic and agreed with Moscow to partition Ukraine. This culminated in the Peace Treaty of Riga in March 1921, which recognised Soviet Ukraine instead of the UPR.

In contrast, despite Russian propaganda about the new “partition” of Ukraine in 2014 and 2022, referring to Poland’s alleged intentions to divide the country, Polish support of Ukraine in the ongoing Russian war is one of the most consolidated across the left-right political spectrum. Since February 2022, Warsaw has spent the highest portion of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) among 38 countries – almost 5% to aid Ukraine.

In absolute numbers, by September 2024, half of military aid and weaponry for Ukraine’s defence efforts was provided by the United States. Meanwhile, Russia has consistently used disinformation aimed at influencing the foreign policy of many of Ukraine’s partners, primarily – the US. These efforts exploit political polarisation between Republicans and Democrats regarding support of Ukraine. The Trump-promoted American isolationism, especially regarding European affairs, echoes the Polish one from 1920.

These historical parallels show how the worst-case scenario for Ukraine in the ongoing war would be to give up territories in exchange for new paper security assurances, only for those promises to be breached soon thereafter.

Peace in Ukraine: attempts to settle the war

By August 2024, at least 25 variations of peace proposals had been put forward by various governments, think tanks and independent scholars. However, as of the beginning of 2025, no diplomatic solution to the ongoing Russo-Ukrainian war has been found yet.

On the one side, the Russian delegation presented capitulation demands to the Ukrainians on 7 March 2022, and negotiations continued until mid-April. On the other side, supporters of a peace-through-strength approach rallied behind Ukraine’s 10-point peace plan, first announced by the President of Ukraine in November 2022 and developed further in October 2024 into the Victory Plan. Other alternatives constitute a peace-at-any-cost grouping and are similar to “China’s position on the political settlement” (2023), which morphed into the China-Brazil 6-point plan in May 2024. The key issues dividing policymakers and scholars when assessing the prospects for peace between Russia and Ukraine include:

– Handling the occupied territories

– Ukraine’s freedom to pursue independent foreign policy

– Whether to pressure armistice or seek formal peace agreement

– Future regional security architecture.

Let’s take a closer look into these different approaches.

What Russia says about peace

The Russian vision of peace is based on the principle that might makes right. Among its original demands of 7 March 2022, Moscow pressed Kyiv to legally recognise the loss of territories, reduce the size of the army, cede political independence in internal and foreign affairs (e.g. enforce Russian language and oversight in all spheres of life and administration and renounce the right of joining military and geopolitical alliances), give up sovereignty over the use of force to Russian troops, which could remain in Ukraine indefinitely. Further rounds of talks continued into April 2022 and are most widely known for the Istanbul Communique. According to Eric Ciaramella from Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, the communique represented “merely a softer version of the Ukrainian capitulation” draft. Negotiations stopped after the liberation of Ukrainian territories revealed the scale of Russian war crimes.

As of 31 October 2024, the official goals of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, as stated by the permanent representative of Russia to the UN Vassily Nebenzia, remained “in force and unchanged”. Nebenzia also emphasised that Moscow “will not allow any freezing of the conflict”. These conditions, if accepted, would have effectively neutralised Ukraine as an independent state and formalised its subjugation by Moscow.

China and Brazil peace plan

China’s proposals, along with similar efforts, call for an immediate ceasefire but effectively appease the aggressor. They constitute what Norwegian sociologist Johan Galtung in 1969 called a “negative peace” or simmering violence to establish a façade of order. None of the Chinese proposals recognised the ongoing war as an interstate conflict or identified Russia as the aggressor. Instead, they call it a “Ukraine crisis”, adopting the Russian narrative of an internal Ukrainian problem that requires external (Russian) intervention. This diplomatic alignment draws on the “no limits” strategic partnership between Moscow and Beijing, announced in February 2022, echoing the 1939 Molotov-Ribbentrop pact between Moscow and Berlin.

China-led roadmaps focus on:

– Promoting peace talks based on the current frontline as a reference point;

– Advocating for the removal of sanctions against Moscow;

– Redesigning regional security architecture to favour Russian interests.

These proposals appear to represent the minimum concessions that Russia might accept without compromising its geopolitical position or losing face.

Ukraine’s Peace Formula

Advocates of Ukraine’s plan pursue a peace resolution that upholds the existing international legal framework. The proposed formula prioritises:

– The withdrawal of Russian troops from all occupied territories

– Restoration of the territorial integrity of Ukraine

– The return of deported and imprisoned Ukrainians

– Reparations and accountability for war crimes

Kyiv argues that Moscow will not reason unless coerced to do so. To compel Russia into peace, Ukraine seeks military aid to achieve battleground victories, obtain weapons of deterrence and legally binding security guarantees – bilateral with individual states or collective as within the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO). Ukraine insists that any potential concessions to the aggressor must be determined solely by Kyiv. It is an ambitious plan which requires intensive and unwavering commitments from international partners.

The cost of a settled peace in Ukraine

The core problem in contemplating peacebuilding between Ukraine and Russia is that Moscow cannot be trusted. In 1795, Immanuel Kant defined trust as the compulsory basis for establishing and maintaining peace. However, Russia’s history of breaking agreements underscores its unreliability. Only a few among many examples include:

– 1919: Moscow violated the obligations it undertook in the 1918 Peace Treaty of Brest-Litovsk once geopolitical circumstances shifted in its favour.

– 1996: The Khasavyurt Truce, which ended Russia’s failed invasion of the Chechen Republic of Ichkeria, served merely as a pause for Moscow to rebuild its forces and launch a renewed invasion under a fabricated pretext in 1999.

– 2014: Russia breached the assurances of the 1994 Budapest Memorandum, which guaranteed Ukraine’s territorial integrity and political independence.

– 2015: Moscow failed to comply with the Minsk II ceasefire agreements to withdraw foreign troops and heavy weaponry from Ukraine or to restore Kyiv’s control over the state border in Donbas.

– 2022: The Kremlin expanded its invasion of Ukraine.

If Ukraine is forced to settle for peace on Moscow’s terms, historical parallels suggest dire consequences.

Unchallenged, Russia will continue:

1. Oppressing people on the occupied territories of Ukraine

Russians mistreat surrenderers and the occupied population. In his book, The Gates of Europe: The History of Ukraine, Serhii Plokhy recounts that in March 1918, Russian invading forces executed captured Ukrainian soldiers. In November 1920, they mass murdered 50,000 capitulators in Crimea. Russians massacred more than 1,100 civilians only in Bucha near Kyiv in March 2022, and since then, tortured or raped tens of thousands of men and women, children and elders, slaughtered and dumped into mass graves prisoners of war and civilians throughout the captured territories. Immanuel Kant called such enemies “wrong in the highest degree”, who “hand everything over to savage violence, as if by law, and so subvert the right of human beings as such”.

2. Committing genocide targeted at Ukrainians

Historical and ongoing patterns reveal that Russian impunity enables further terror and genocide against Ukrainians. In the aftermath of the 1918-1921 Russian war against the Ukrainian nation, a short initial period of pacification through concessions to the local population followed by a decade of terror. Deportations and resettlements, cultural appropriation and material dispossession, political imprisonments, executions and ideological terror. This culminated in the 1932-33 artificial famine called the Holodomor, in which Moscow killed several million people, predominantly Ukrainians as researched, among others, by historians Anne Applebaum, Serhii Plokhy and Timothy Snyder. Retrospectively, the Holodomor was recognised internationally as the Moscow regime’s genocide against Ukrainians.

In the 21st century, Moscow renewed efforts to destroy the Ukrainian nation and erase Ukrainian ethnos. Since 2014, Russians have deported millions of Ukrainians from the occupied territories with children subjected to Russian reeducation and indoctrination. Occupation authorities have been enforcing Russian passports and language on the local population at penalties of denial of social services, medical treatment, and education. Meanwhile, vacated properties and depopulated areas have been repopulated with millions of Russians.

In their ongoing war against the Ukrainian nation, Russians systematically commit not just a few but all the acts listed under the legal definition of genocide in Article 2 of the Genocide Convention – “killing, causing serious harm, deliberately inflicting physically destructive conditions of life, imposing birth prevention measures, and forcibly transferring children to another group”. The coordinated totality of these acts, public and written statements and comments of the Russian leadership and its lieutenants, individual intentional (as in interviews, social posts) and unintentional (as in intercepted calls) public testimonies about Ukrainian nation and people – all prove the genocide defining “intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical (…) group”.

The host of the Russian state television consistently put it, “There should be no Ukraine any longer” (2:22), “as State Duma deputy Tolstoy said, we will kill all of them” (3:09).

Therefore, an apparent cost of a settled peace with Russia is a genocide of the Ukrainian nation in part or in full.

3. Controlling natural and industrial resources through colonial means

Moscow continues seeking colonial control over Ukraine’s population and its natural and industrial resources. Designated with a mere 2% of the Soviet Union’s territory and under 20% of its total population, starving Ukrainians were made responsible for 38% of all grain deliveries to that state in 1932. With Ukraine decimated through the 1930s, the remaining 28 million were integrated into the Soviet totalitarian machine and provided Moscow with nearly 20% of the Soviet Union’s gross industrial output. It included up to two-thirds of its total metals and energy production, most of which were utilised in the military-industrial complex.

The Holodomor of 1932-1933. Photo by: Alexander Wienerberger.

Between 2014-2022, the Russian Federation is estimated to have already increased its de-facto population by 7% at the cost of up to ten million occupied or deported Ukrainians. The Washington Post estimated that Ukrainian territories under Russian occupation, as of August 2022, held $12.4 trillion worth of energy deposits, metals, and minerals. As in the 1920s, in the 2020s Ukraine remains the key for Russian economic and military empowerment as an empire.

4. Attacking other countries using subjugated Ukrainians as a force

A peace agreement which subordinates Ukraine to Moscow would endanger other states in the region by facilitating an expansion of Russian aggression. In the 1939-40 invasion of Finland, more Ukrainians of the Soviet army were killed than Finns. Allied with Nazi Germany, Moscow started the Second World War in September 1939 by sending troops into previously independent Poland, Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia. Over the following 21 months, the Soviet regime deported hundreds of thousands and murdered tens of thousands of locals in these occupied territories.

Since February 2022, recognising these tragic historical lessons, the above-mentioned countries have significantly ramped up their collective military and defence capabilities anticipating the Russian further invasion of Europe. Moscow needs Ukraine subjected to its control to reconstitute its strength and continue the invasive expansion of the Russian World.

How do Ukrainians see lasting peace?

Any war resolution proposals must reflect people’s will. A well-grounded solution can be constructed only through directly engaging with those most affected, avoiding misrepresentation and possible harm from speaking on behalf of others out of privilege or selfish motives. For this, I analysed several representative social surveys of Ukrainian and Russian public opinion and complemented it with insights from personal communication with Ukrainians as the side most affected by the war. To secure opinion-based answers, I asked them an open-ended question: “How do you see the ongoing Russo-Ukrainian war ending and whether a stable long-term peace is viable upon its conclusion?”.

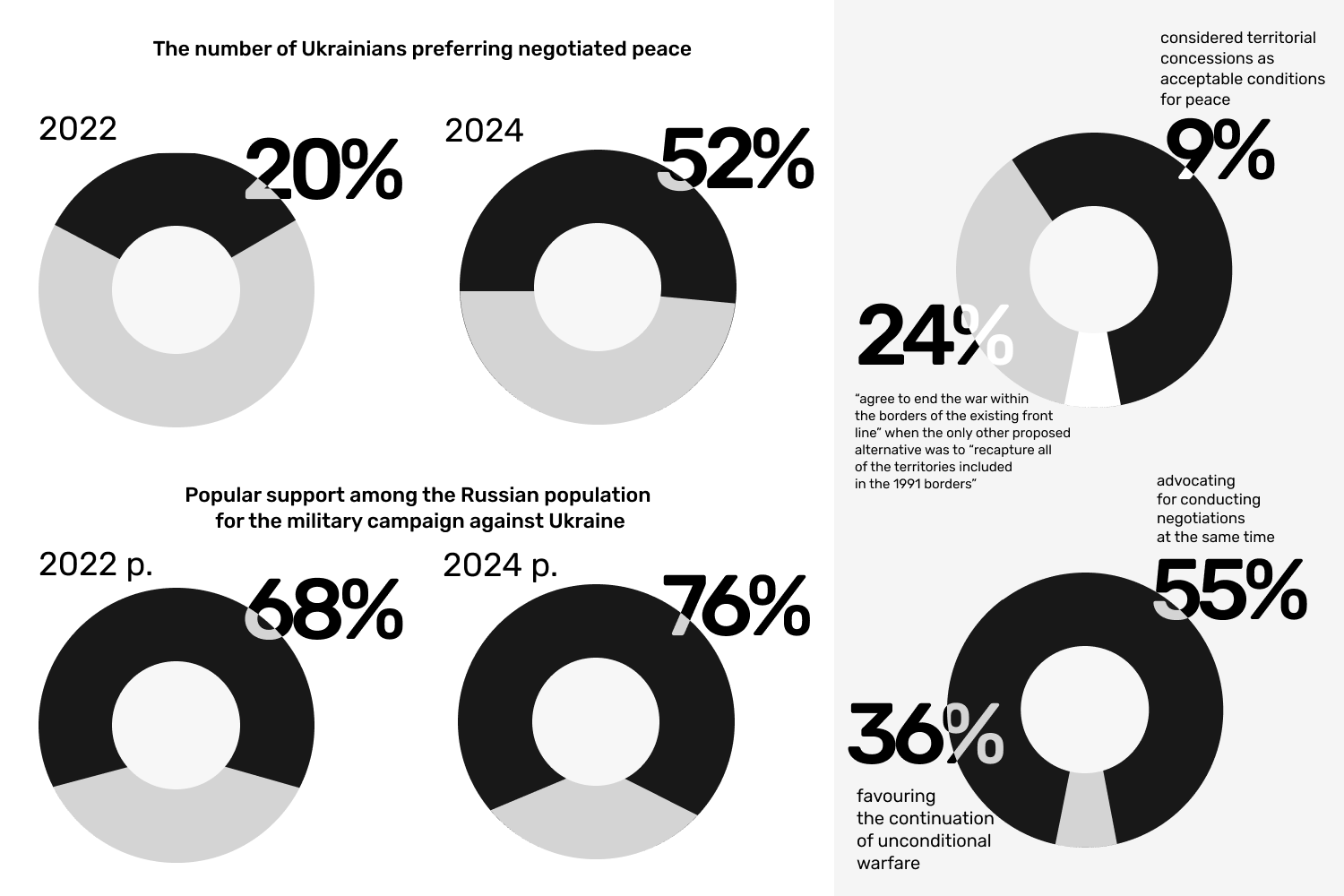

Social surveys reveal that, by the end of 2024, less than a quarter of Ukrainians were willing to make concessions to the Kremlin in exchange for peace, while support among Russians for a military invasion grew even stronger.

The Gallup poll reported an increase in the number of Ukrainians preferring negotiated peace, from 20% in 2022 to 52% in 2024. However, only 27% think that the government “should be open to making some territorial concessions”. The survey by the Ilko Kucheriv Democratic Initiatives Foundation, conducted in cooperation with the Razumkov Center’s sociological service in August 2024, found that only 9% of the respondents considered territorial concessions as acceptable conditions for peace. The International Republican Institute reported that 24% of the respondents chose to “agree to end the war within the borders of the existing front line” when the only other proposed alternative was to “recapture all of the territories included in the 1991 borders”.

Surveys by the Russian non-governmental research organisation Levada Center demonstrate consistent popular support among the Russian population for the military campaign against Ukraine, rising from 68% in February 2022 to 76% in October 2024. Preferences within this support have remained stable, with 36% favouring the continuation of unconditional warfare and 55% advocating for conducting negotiations at the same time. Although a similar percentage of both sides are open to negotiations according to the polls, their expectations are rather opposing: Ukrainians seek the return of occupied territories, while Russians see negotiations as a tool to legitimise their conquest.

In the minds of Ukrainians, external military aid is the defining factor for the outcome of this war, while international security commitments are the only hope to secure peace. Seventy five percent of Ukrainians believe they will “succeed in the war, provided that it has the proper support from the West”, according to the Kyiv International Institute of Sociology. Russians echo the significance of Western military support for Ukraine in this war with a supermajority of 86% surveyed being concerned about it. Notably, only 40% of Russians suggested they would have cancelled the invasion of Ukraine if they could go back in time and change it.

According to the Democratic Initiatives Foundation, only 4% of Ukrainians are confident that Russians will not invade again if the ongoing war comes to an end. About 62% of respondents see security guarantees from other countries as a key potent deterrence of the Kremlin. The International Republican Institute has recorded a significant increase in support for NATO membership, with 75% of Ukrainians indicating they would vote to join the alliance in a referendum. Two and a half years ago the number was 59%. On the one hand, the results are disheartening because they demonstrate a high predisposition for the renewed Russian invasion in the future. On the other, they indicate that people see collective military commitments and deterrence as the most potent means for establishing longer and more stable peace.

Brave Ukrainians strongly argue that it is futile to think that Ukrainians could secure better peace terms by negotiating with Russians now than through fighting them out. In October-November 2024, I asked an open-ended question to several Ukrainians about their perspectives on peace. Their responses provide valuable insight:

– Artem, a frontline volunteer, recalls that the first weeks of the full-scale invasion revealed the Russian army to be far less effective than many had feared. He believes that the liberation of Crimea and Kherson regions is a feasible goal.

– Kostiantyn, from Lviv, advocates for investment in innovative warfare, such as drones, and resilient defence strategies to achieve victory.

– Roman, from Kyiv, feels it imperative, along with a military struggle, to continue developing a consolidated society and cooperating with international partners.

– Victoria, from Cherkasy, reasons that invaders, like any criminals, must be punished; otherwise, impunity will invigorate their violence.

– Olia, a native of Mariupol, expresses scepticism about the return of the occupied territories to Ukraine under any presently conceivable ceasefire conditions.

Ultimately, no one believes in restoring the internationally recognised borders via diplomacy alone. People see true regional peace as an achievable goal only through potent collective military deterrence and the collapse of the current Moscow regime. Roman emphasised the vitality of acquiring long-range heavy weapons to bolster Ukraine’s military. Victoria felt it necessary to rebuild nuclear capabilities for deterrence, while Artem strongly advocated for military alliances among regional states that share concerns about the Russian threat. There was a clear consensus among those I spoke with: any compromise settlement would inevitably result in Moscow launching another invasion within 5 to 20 years.

Peacebuilding strategies: Immanuel Kant and peace theories

Post-Second World War peace theories often unduly discard military force as a required pillar of peacebuilding. Studies focus instead on social and global justice, urge compromise and dialogue between states, question the morality of state military responses, promote non-violent resistance and address structural violence within states, foster forgiveness and reconciliation. Examples of such studies include Structural Violence as a Human Rights Violation by Kathleen Ho, The Work of Global Justice by Fuyuki Kurasawa, War of the Worlds: What about Peace? by Bruno Latour, Not again by Arundhati Roy, Power and Struggle by Dr. Gene Sharp, Violence, Peace and Peace Research by Johan Galtung, Pretending Peace: Kant, Amery, and Political Trust by Marguerite La Caze.

The most common advice among those studies is to stop using counterviolence in response to inflicted violence. Recently, the Pope echoed this sentiment by urging Ukraine, the victim of the Russian invasion, to raise a “white flag” of negotiations with Moscow in the name of “saving lives”. The theoretical argument of such an approach assumes the opponent is reasonable and just. Unfortunately, Moscow’s actions have proven otherwise. It subverts reason to falsehood and the rule of law to military might and direct violence, and conducts the war of subjugation and extermination. Against such an “unjust enemy”, Kant asserted in 1797, “there are no limits to the rights of an injured state (…) to use those means that are allowable to any degree that it is able to, in order to maintain what belongs to it.” Kant believed that retribution is a necessary moral response and should be delivered proportionally to crimes committed by wrongdoers. In other words, defeating an invasion and punishing the aggressor to secure the state, its people and territories is a compulsory precondition in addressing peace in Ukraine.

Special forces soldiers of the Special Operations Alpha Unit of the Security Service of Ukraine work with a Ukrainian kamikaze drone. May 2024. Photo by Karyna Piliuhina.

True peace requires not merely a cessation of hostilities but permanency of law-governed conditions. In the 1795 Perpetual Peace, Kant argued against treaties with loopholes that could lead to future wars. He also believed that not interfering in the internal affairs of other states was the preliminary step towards peace. One of his key ideas for lasting peace is that international law must take precedence over a nation’s own judgment in international relations. Similar to how people form a state where everyone willingly “relinquished entirely his wild, lawless freedom in order to find his freedom as such undiminished, in a dependence upon laws, that is, in a rightful condition”, to facilitate cooperation and mutual respect states must willingly subject themselves to international law as equal members of a global community “unless [they] want to renounce any concepts of right”. If Russia refuses to follow the common legal code of a “league of nations,” it cannot live in harmony with other states. By doing so, it violates their right to peace.

Collective international deterrence could be a viable long-term solution for peace in Ukraine and Europe. In the 1797 Metaphysics of Moral, Kant defined “the right to an alliance (confederation) of several states for their common defence” against external threats as an integral part of the right to peace. This also includes the right to guarantees for a lasting peace once it is achieved. Ukraine’s resistance against the Russian invasion resonated deeply with similar traumatic experiences of the states in the Baltic Sea region. Judith Butler once suggested that shared vulnerability could create a collective responsibility. Ukraine has been increasingly seen as part of a common consolidated identity in the Baltic states, positioning Ukraine as an informal member of the region. Therefore, the military alliance or confederation between Ukraine, Poland, Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia and, potentially, Finland could be considered an alternative pathway towards sustainable peace in the region bordering the Russian World.

Supporting this idea, the Northern Group — a coalition of twelve Northern European countries — declared on 20 November 2024 the strengthening of their military cooperation with Ukraine and of the collective “deterrence and defence posture in the face” of Russian direct threat to regional security.

In conclusion

This article demonstrates that the ongoing Russian war against Ukraine is both colonial and genocidal, reflecting a pattern of similar acts from the past. True peace is conceivable only with the collapse of the Russian imperial mindset and regime. To guarantee a long-lasting peace, Ukraine should join or establish a new military alliance or confederation of states capable of collectively protecting themselves and deterring future aggression from Russia.

Moscow started its colonial subjugation of Ukraine in 1654. Despite the will of the Ukrainian people, Moscow enforced the Russian World on them in 1918 and in 2014. In both cases explored in this study, Moscow abated its initial ambitions and negotiated only after facing a resolute military response, bolstered military support from Ukraine’s allies or partners. The current Russia-Ukrainian war persists because Russian imperialist demands are not compatible with Ukrainian independence. Alternative diplomatic proposals often suggest impunity and appeasement of the aggressor rather than a potent resolution. After consistently breaching formal and conventional agreements over decades, Moscow cannot be considered a trustworthy diplomatic actor. Moreover, the pattern of hideous Russian crimes in this war falls under the legal definition of genocide, echoing the atrocities of 1930s. If history is any indicator, the more lands and people Moscow captures and keeps, the more resourceful it becomes to expand its conquest soon enough.

Considering the outcomes of the comparative analysis of the ongoing Russo-Ukrainian war with the events of 1918-21, as well as broader historical context and the voices of the affected people, the peacebuilding mantra about compromise and dialogue based on mutual respect and trust cannot be applied in this case fairly. Instead, peacebuilding should begin with enabling Ukraine, the wronged country, to exercise the two foundational Kantian rights. Firstly, to use all means necessary to protect itself from invasion. Secondly, to unite with other threatened states to defend against the common enemy, which threatens regional peace by conducting the genocidal conquest. Ultimately, the goal of such an alliance is to deprive the aggressor of its power to wage such wars and, at the very least, to guarantee peace through deterrence.