During the Second World War, many Ukrainians were among the prisoners held in Nazi concentration camps.

Written by

Olesia IsaiukResearcher at the Center for Research of the Liberation Movement, Lontskoho Street Prison Museum-Memorial

The experiences of those who ended up in Auschwitz — the largest of them — reflect the complexities of that era, from political persecution to personal circumstances. In total, almost 120,000 prisoners from Ukraine passed through Auschwitz; 86,000 of them were Transcarpathian Jews.

This article was originally created for Local History magazine and translated by the Ukraїner International team.

Fighting for someone else’s empire, only to be killed by another

One of the first Ukrainian prisoners at Auschwitz, Bohdan Komarnytskyi, was arrested for alleged involvement in illegal trade in Kraków, Poland. He was transported to the camp on 30 August 1940 — just a few months after Auschwitz opened — and registered as prisoner number 3637. As the prisoner population eventually swelled into the hundreds of thousands, those with three- or four-digit numbers earned a degree of respect, even from the guards, for having survived the camp’s most brutal early period.

Two months after his arrival, Komarnytskyi succeeded in building relationships with prisoners who held influence within the camp hierarchy — even some within the administration. Over time, he became what was known as a “useful Heftling”: someone relied upon by both work team supervisors and the camp authorities. This status enabled him to help fellow Ukrainians — members of the Organisation of Ukrainian Nationalists (B), also known as OUN-B, imprisoned for proclaiming the Act of Restoration of the Ukrainian State, as well as fugitive Ostarbeiters (Eastern forced labourers). He arranged physically lighter duties for them, shared food, and offered other support wherever possible.

OUN-B

Organisation of Ukrainian Nationalists (B) was a nationalist revolutionary political organisation formed by Stepan Bandera following the split of the unified OUN. On 30 June 1941, the group proclaimed the Act of Restoration of the Ukrainian State. The letter (B) denotes the faction led by Bandera, while (M) refers to the wing headed by Andrii Melnyk.

The entrance to the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp. Photo: Wikipedia

In the autumn of 1941, prisoners of war from the Red Army — including many Ukrainians — were brought to Auschwitz. The first group of 450 arrived in early September and consisted primarily of political officers, known as commissars. One of these groups was brought to the camp just as the Nazis were preparing for the mass extermination of Europe’s Jews. The final decision on this genocide was formalised at the Wannsee Conference in January 1942.

On 22 September 1941, the Nazis tested what would become one of their main instruments of mass murder: Zyklon B gas. Pellets were thrown into a sealed room filled with wounded and sick prisoners of war, including Ukrainians. This trial marked the beginning of systematic killings using poison gas.

Shortly afterwards, beginning on 7 October 1941, nearly 14,000 Soviet prisoners of war were transported to Auschwitz in smaller groups over the course of a month. They were assigned to the most punishing labour units, known as penalty teams. Held in a segregated section of the camp, they were given no warm clothing and were barely fed — receiving only a weak brown “tea”, thin “soup” containing scraps of potato and rutabaga, and a loaf of stale bran bread to be shared among six people.

One of these prisoners, Andrii Pohozhev from Donetsk, later recalled, “Columns of naked Soviet prisoners stood in rows all that time, with sick and dead people lying on the concrete in front of them. During roll call, their number grew as more men collapsed out of the ranks.”

Pohozhev was among the very few Soviet POWs who survived Auschwitz. In the 1960s, he wrote a memoir of his experience, which was eventually published in the 2000s.

Auschwitz I, January-February 1945. Photo: Central State Audiovisual and Electronic Archive of Ukraine

Nearly a thousand of the 14,000 Soviet prisoners of war sent to Auschwitz were Ukrainians. Most had been captured during the battles for Kyiv and near Minsk in August–September 1941. Typically aged between 30 and 40, they came from villages or small towns — ordinary soldiers, and occasionally sergeants. This was a kind of men who generally formed the backbone of armies. Yet in this case, they were Ukrainians fighting for someone else’s empire — the Soviet Union — only to perish in the death machinery of another.

Even under desperate conditions, some still found ways to resist. As is common in places lacking proper hygiene, Auschwitz became a breeding ground for disease, including typhus, which is spread by lice. Prisoners began secretly transferring lice onto their executioners — block officers, wardens, and kapos. Later, Danylo Tchaikovskyi, a member of the OUN-B imprisoned at Auschwitz, recalled in his memoirs that all those who received this dangerous “gift” eventually died of typhus.

Andrii Pohozhev also remembered how, in response, prisoners of war were later forced to stand with their hands open, palms up, during roll calls and inspections by the guards.

By early March 1942, only 600 to 800 of the original 14,000 Soviet POWs remained alive in Auschwitz. Those who survived were transferred to the newly constructed Auschwitz II (Birkenau) camp.

The “Bandera Group”

While Soviet prisoners of war were already imprisoned in Auschwitz, another group of detainees — members of the Organisation of Ukrainian Nationalists (Bandera faction, OUN-B) — was arrested en masse by the Nazis on 15 September 1941. This was a retaliatory measure for their refusal to withdraw the Act of Restoration of the Ukrainian State, proclaimed earlier that year. Some so-called Banderites had been arrested even before that date; for instance, Mykola Klymyshyn was captured near Makariv in the Kyiv region on 7 September 1941.

Initially, the detainees were held in local prisons such as Lviv’s infamous Lontskoho Street Prison and another one in Ivano-Frankivsk. They were then transferred to Montelupich Prison in Kraków — commonly known as Montelupa. On 20 July, they were sent to Auschwitz.

Among those imprisoned were Vasyl and Oleksandr Bandera, the brothers of Stepan Bandera.

Stepan Bandera

A complex and controversial figure in the history of Ukraine. Bandera is regarded by some as a leader of the nationalist struggle for Ukrainian independence from both Poland and the Soviet Union, while others view him as a collaborator with Nazi Germany, implicated in crimes against Jews and Poles. From 1942 to 1944, he was imprisoned by the Nazis in the Sachsenhausen concentration camp. In 1959, Bandera was assassinated in Munich by a Soviet KGB agent.

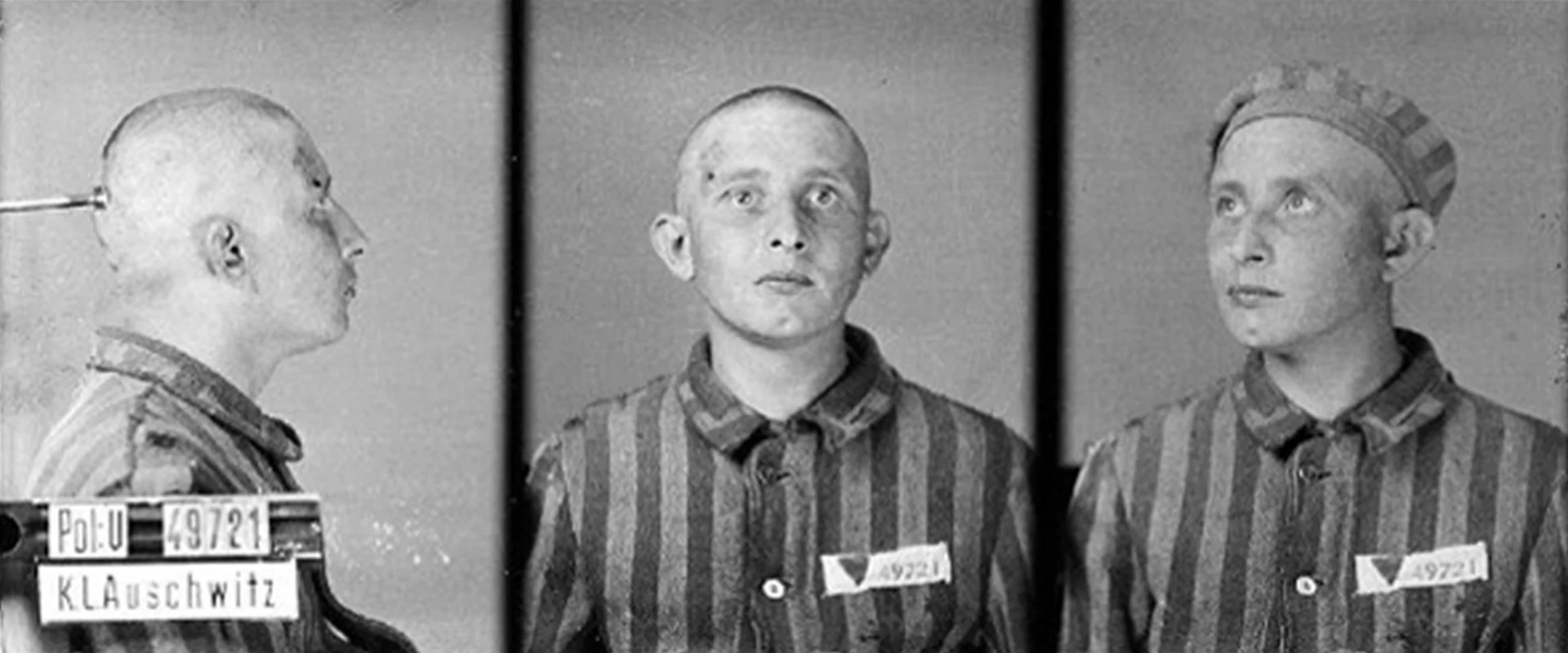

Vasyl Bandera, photo from Auschwitz. Source: Wikipedia

The first few weeks in Auschwitz were tragic for the imprisoned Banderites. They were immediately assigned to the so-called Neubau team — a group of prisoners forced to work on the construction of new barracks. The team’s warden, a Pole named Józef Kral, saw this as an opportunity to exact revenge on the OUN for the assassination of Polish Interior Minister Bronisław Pieracki, known for his brutal pacification policies against Ukrainians.

Among those targeted was Vasyl Bandera, who had worked in the OUN’s propaganda department in Stanislaviv. He was subjected to severe torture in the early days of his imprisonment.

“They dragged him into the cellar while he was working, still covered in cement, and threw him — clothed — into a barrel of water. Then they scrubbed his face and head with a red brush. After that, they forced him to continue working, running with a wheelbarrow and carrying cement, before dragging him back to the cellar to be ‘washed’ again,” recalled Petro Mirchuk, a fellow Banderite.

After a full day of such abuse, Vasyl was taken to the camp hospital — the so-called revir — which prisoners grimly referred to as a deathbed. He died there on 22 July 1942, the same day his brother, Oleksandr Bandera — who had worked in the Romanian division of the OUN — arrived at the camp. Oleksandr died just days later.

Another supporter of Bandera, Dmytro Yatsiv from the Stryi region, did not survive his first month in Auschwitz. He died on 19 August 1942.

The Assassination of Minister Bronisław Pieracki

The political assassination of Polish Interior Minister Bronisław Pieracki in 1934 was carried out by the Organisation of Ukrainian Nationalists. Pieracki was one of the key figures behind the so-called “pacification in Galicia” — a series of planned repressive actions targeting the Ukrainian population.On 8 August 1942, just two weeks after the first wave of arrests, the next group of OUN members arrived at Auschwitz. Among them was Mykola Klymyshyn, who narrowly escaped being beaten to death by Polish prisoners. This incident led to contact between the Banderites and former Polish army officers imprisoned in the camp. From that point on, they no longer feared hostility from the Polish inmates — but the threat from wardens and other camp “authorities” remained very real.

An unexpected development helped improve their situation. When Maria Dumini, the Italian-born wife of Oleksandr Bandera and a relative of Italian Foreign Minister Count Galeazzo Ciano, received the standard Auschwitz notice that her husband had died suddenly of a “heart attack,” she immediately raised the alarm. Her intervention prompted an investigation, and in an effort to avoid further politically sensitive deaths, the Nazi authorities decided to house the Bandera Group together in Block 18.

A year later, at the end of October 1943, the Bandera Group was joined by a group of Ukrainian prisoners from the so-called “Lviv transport” — those arrested and imprisoned at the Lontskoho Street Prison in Lviv, and subsequently sent to Auschwitz.

Soon, the Banderites established a system of mutual aid. It extended beyond their own ranks to include forced labourers, surviving prisoners of war, and other Ukrainians from the central and eastern regions. The principle was straightforward: those who had access to additional food, clothing, or resources were responsible for helping physically weaker comrades. Mykola Klymyshyn oversaw this support network.

Thanks to this grassroots “rescue organisation”, the relatively small Bandera Group managed to preserve the majority of its members. According to some estimates, 375 members of the group survived to take part in the “death march” of winter 1945, when Auschwitz prisoners were forced westward on foot through the bitter cold.

Ukrainian Ostarbeiters and children in Auschwitz

Among the Ukrainian prisoners in Auschwitz, the majority were Ostarbeiters — civilians who had been forcibly taken to work in Nazi Germany. Many of them attempted to escape, but were captured and sent to the nearest concentration camp. Those who ended up in labour camps were considered comparatively “fortunate”, but those arrested in regions like Silesia, Kraków, or Zakerzonia were often sent to Auschwitz.

Among the victims were thousands of Ukrainian boys and girls. For most of them, only brief records remain: names, camp numbers, and the charge of “unauthorised departure from place of work”. In some cases, a listed profession is all that survives to mark their existence.

Ostarbeiters

The term Ostarbeiter literally translates as “Eastern worker”. This name was used to describe people taken by the Nazis for forced labour from Eastern and Central European territories.

Photo: Pavlo Ardan

There were often teenage boys among the Ukrainian prisoners — children, in effect. “They took a child from Ukraine, but he missed his mother. Along the way, they caught him and sent him to the camp, as if he were a delinquent,” wrote Danylo Tchaikovsky in his memoir I Want to Live!

Perhaps the most well-known case is that of Vadym Boyko, a sixteen-year-old from Skvyra in Kyiv region. He had been forced to work in the mines near the town of Boiten. After some time, he escaped with a friend. Somewhere near Kraków, the boys were apprehended — ironically, close to a military installation. Suspected of being underground resistance scouts, they were not handed over to the police, but instead to the Gestapo in Kraków.

What followed was a months-long investigation involving torture. Eventually, Vadym was deported to Auschwitz, where he spent the next two years as prisoner number 180649.

Photo: Pavlo Ardan

The only hope of survival for these children often lay in the protection of older prisoners. While political prisoners frequently tried to shield them, others — particularly criminal inmates — exploited their vulnerability. At best, these children were turned into servants; at worst, they became victims of sexual abuse.

The story of Mykhailo Maiboroda stands out. He arrived at Auschwitz in November 1942 as a thirteen-year-old, registered as prisoner number 75831. Fortunately, he came under the care of the Banderite prisoners. Mykhailo was born in 1929 in the Luhansk region (though some memoirs mistakenly cite the Poltava region). He had been taken to Germany with a group of adults selected for forced labour. He remained in Auschwitz until February 1944, when he was transferred to Buchenwald. After that, his fate is unknown.

Lemkos, Podolians, Jews in Auschwitz

In February 1943, several hundred people from the Lemko village of Krynytsia and neighbouring settlements — Labovets, Povroznyk, and Kotov — were deported to Auschwitz. Many shared the same surnames: Ondych, Bladych, and Sivak. The youngest of the Ondychs was born in 1905, making him 38 at the time of his death in the camp. Others were even older, born in the 1870s. Maria Bladych, the eldest of her family, was born in 1885; the youngest Maria Bladych was not yet fifteen when she died. Members of the Sivak family, from the oldest to the youngest, also perished behind the barbed wire — none survived beyond the end of that year.

To this day, the reason for the arrest and deportation of these Lemko families remains unclear. The causes may have varied: anything from failure to pay food taxes to political suspicion. In many cases, younger family members may have been involved in resistance activity, or the families may have been punished for hiding individuals considered “undesirable” by the occupying forces.

Lemkos

An ethnographic group of Ukrainians originating from Lemkivshchyna, a mountainous region that spans parts of present-day Ukraine, Poland, and Slovakia. The group has a distinct cultural identity. Notably, the renowned American artist Andy Warhol was of Lemko descent.

Photo: Pavlo Ardan

In the summer of 1943, groups of young men, clearly exhausted from forced labour, began appearing in Auschwitz. These were likely natives of the Vinnytsia region, forced to work on the construction of Hitler’s Werwolf headquarters. Records from the camp hospital and new prisoner intake show a marked increase in inmates from Vinnytsia beginning in autumn 1942 and again from August 1943. Most of them perished in Auschwitz.

The most tragic fate, however, befell the last wave of Ukrainian prisoners: the Jews of Zakarpattia (Transcarpathian Jews). Beginning on 12 May 1944, thousands were deported to extermination camps. They were crammed into cattle cars and transported via Košice, where Hungarian guards handed them over to the Germans, who then continued the deportations to Auschwitz. No food or water was provided during the journey — people had only what they had managed to take from the ghettos. Many did not survive the trip.

Nearly 86,000 people endured this way of the cross. Upon arrival at Auschwitz, they underwent the infamous “selection”: children, the elderly, and the sick were sent straight to the gas chambers. The others were assigned to forced labour — often the most grueling and senseless tasks. Fewer than one in five survived.

How many Ukrainian prisoners were held in Auschwitz?

According to the Ukrainian Institute of National Memory, approximately 120,000 prisoners from Ukraine passed through Auschwitz. Among them were 86,000 Transcarpathian Jews, who had been citizens of independent Ukraine for just a few days following the declaration of statehood by Carpathian Ukraine on 15 March 1939.

The majority of these prisoners died — killed by brutal labour, abuse, beatings, starvation, disease, and exposure. Most of the Transcarpathian Jews were murdered in the gas chambers immediately upon arrival.

Photo: Pavlo Ardan

Ukrainians in Auschwitz were largely invisible — not because they were absent, but because the Nazis registered prisoners by official nationality rather than ethnic identity. As a result, Ukrainians from western regions were often recorded as Poles; those born in the Soviet Union were listed as Russians or Soviet citizens; others were classified as Czechs or Romanians, depending on their region of origin.

Omelian Koval, a member of the OUN (B) who survived Auschwitz and later emigrated to Belgium, wrote about the absurdity of this practice in his memoirs, “What a humorous spectacle it was when our Ukrainian group of seven received four different classifications: two of our friends from Zakarpattia were registered as ‘C’ (Czechs), three from Galicia received ‘R’ (Ruthenians), one was given an unmarked number because his father had lived in Warsaw and used a Nansen passport, and one was marked with a black triangle and ‘R’ (Russians) because he was from Eastern Ukraine. So, seven Ukrainians had four different nationalities.”

While the Nazis took away the health, time, and lives of their victims, in the case of Ukrainians they also erased their national identity. As a result, the full extent of Ukrainian suffering in Nazi concentration camps remains under-researched and insufficiently acknowledged. There is still much to uncover.