Throughout the centuries, the moors of Bessarabia, scattered within the banks of the Dnister, the Danube and the Black Sea, have boasted cultural and ethnical diversity. Local villages were comprised of multinational families, where it was quite common for mother to have Bulgarian roots whereas father could have descended from Moldova. In those families, everyone was fluent not only in Ukrainian, but in Moldavan, Bulgarian, and Russian. During the expedition we visited one of those villages, where we met Palariiev family — central characters in this story. For over 10 years now, members of the family with Moldovan origin have been working on the revival of Frumushyka-Nova village, which had been founded back in 18 century and destroyed in the Soviet times. Frumushyka-Nova is a modern replica of the former Frumushyka, which seems to have sprung up to life 60 years later.

In 1946, when the Second World War was already over, the Soviet army was gearing for another war. For this reason, a decision was made to build an armor training battlefield on the moor. To clean the area, they forcibly evicted the residents of Cantemir, Zurum, Roshyia, Kofrumstal, and Frumushyka villages.

Crosses erected in memory of the inhabitants of the villages of Cantemir, Zurum, Roshiya, Kofrumstal and Frumushik, forcibly evicted in 1946.

Andrii Palariiev and his family were relocated to Saratsyk village, 30 km away from Frumushyka. Later, he came back to the neighbouring village Borodino, where his son Oleksandr was born and spent his childhood years. Andrii points at the solitary trunk on the horizon and shares his memories:

— When I was 10 years old, we used to tend sheep behind that tree; and this is the lake where we would go fishing for gudgeons and crucians and then cook them.

When Oleksandr grew up, he decided to restore the place of his father’s youth. Thus, in spring 2006, Oleksandr set his hands to revival of Frumushyka. It all started with trees planting:

— When the members of the committee came to allocate the territory and saw my designed plan — a stake to mark a place for a tree, another stake for the house — they considered it as a far-fetched project. Meanwhile, a tractor dug out holes for trees; in half an hour plants were delivered in the cycle car and water was brought in a barrel. We planted the trees instantaneously. After that, committee members offered their assistance. We were done in two hours.

None of the grown trees were chopped down. The village was reconstructed according to the cartographic records discovered in archives. The old maps depict the Frumushyka River. Back at the times when the river was still crossing that area, the village encompassed 540 houses, 5 mills, 2 schools, a specialized training school and a church.

Oleksandr and his sons have reconstructed family estate on the premises of Frumushyka-Nova. This is a typical Moldovan house with people living in the main building, cooking meals in a separate kitchen, and hosting guests in the living room; there is also a separate room for children:

— When my grandfather stepped into this place for the first time, he cried. He sensed the vibes of the house where he had been growing up and which he was forced to leave — tells Mykhailo — Oleksandr’s youngest son.

In the Soviet times, Andrii Palariiev was subject to persecution because he spoke Moldovan. So, he was compelled to switch to Russian. It was not until Andrii turned 75 years old when he began to recollect his mother tongue.

Bessarabian Village

In the course of time, others theme-based houses emerged near the reconstructed Palariiev estate, namely Ukrainian, German, Jewish, Moldovan, Bulgarian, Gagauz, and Russian houses. Thus the family has created an open-air museum called “Bessarabian Village.” The houses were assembled right in the village where material was produced; “lampach” (adobe) — a mixture of clay, straws and muck was used as a basic building material.

Mykhailo believes that Moldovan estate is the most appealing, with a Jewish as a runner-up. The latter is of a great interest as it has two entrances and two exits: you can walk in through one place and walk out using the other. Such design with a corridor and a couple of rooms resembles him modern apartments. The museum houses, which are equipped with WC-and-bathroom facilities, are perfectly suitable for accommodating people.

— I remember the reaction of my grandpa when he saw those facilities in his own house: he was peeved at the fact that WC-room was twice the size of his parents’ bedroom.

slideshow

At first, it seemed like an excellent idea to accommodate tourists in the museum, until they started to touch and move the exhibits. Obviously, the hosts did not like it. As of now, the visitors of Frumushyka-Nova may stay in the guest-houses:

— There are boots in every house, lest the weather should be nasty with the rain. So, you can put them on and go outside.

Houses with national coloring even served as an overnight accommodation for Romanian and Moldovan consuls.

Sheep

Now, everything is well-equipped with all the required communication lines. Gravel paths connect one house to another, located amid a range of pine trees. Initially, 11 years ago, there was neither water nor electricity supply — nothing but a bare moor.

Oleksandr and his father have always dreamed to tend sheep at that place. So, they built the first farm. For the four years, there was a severe drought. Normally, when on the surface there is one-centimeter crack, it is one-meter deep. Back then, there were 10-15-centimeters cracks:

— Firstly, we did not know what would the sheep drink, and then there were heavy rains. The weather was challenging us. Maybe it was a hint that we should build auxiliary water reservoirs, — tells Mykhailo.

Now, there are about 6 thousand sheep in the household; there were times when this number would reach 12 000. This farm is considered the largest in Eastern Europe where caracul sheep are bred. It turned out to be quite an ordeal to keep such flock of sheep:

— I remember how we lost 1452 sheep in just one day. In summer, there was a sudden decrease in temperature from 35°C to 15°C. In a heavy thunderstorm, sheep were washed down with water. They trampled each other underfoot and cut the wool with their hooves.

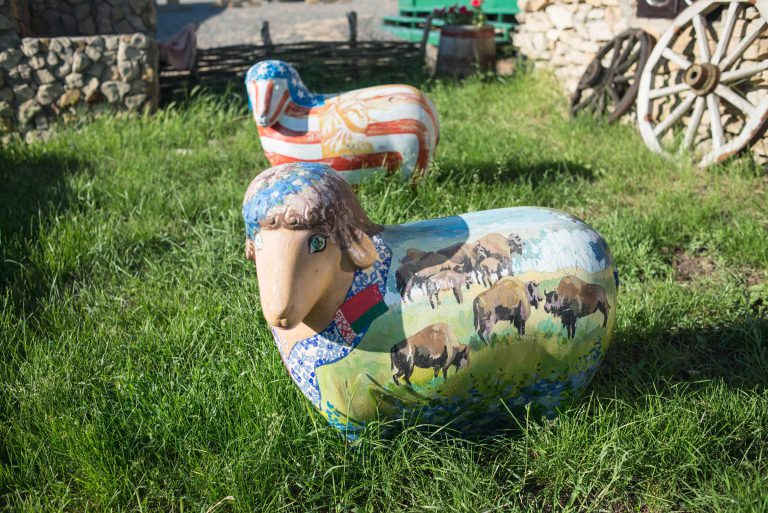

Besides living animals, there are 50 sheep statues. Artists who visited the village painted them with patterns typical of their own culture.

slideshow

Another local story has to do with sheep. In the moor, the Palariievs have set up the tallest in the world monument to the shepherd. Oleksandr assures that all documents for the Guinnesses Book of Records are ready. They are also planning to install the monument to the Dog:

— Ukrainians are a poor nation, but there should be something to be proud of. So, we will take our watchdog to the neighbouring village and take its photo. We will make its monument with large ears! — eagerly tells Oleksandr. This way, we could be included into the list of places with two tallest monuments on the same territory.

Oleksandr

The monument required a considerable investment. Oleksandr puts off with a jest that he does not want to know the precise sum. At the same time, he honestly admits that, being a businessman, he is good with money:

— On the third year of studies, I figured out that after graduation my salary would be 80-90 rubles. And I got used to earning more, — tells Oleksandr.

He was very active during his student years: being 18 years of age he worked in Tiumen. He would often have his nose bleed and fever rising up to 39-40°C due to heavy loads (400-kg-rails) he was carrying as a part of his job. Also, Oleksandr worked in students’ construction brigade in Ukraine, and then in Bulgaria:

— When I was still a student, I knew I wanted to go abroad. As a rule, returning from abroad people could usually afford a car.

Лавка і скульптури з бараном і вівцями біля підніжжя пам'ятника чабану

By the way, the monument to the shepherd was installed due to the economy causes:

— Its cost is equal to that of one kilometer of road surface, and we need 18 km of paved road. So isn’t it more reasonable to construct an object which will require a paved road? — Oleksandr tells with a smile on his face.

Oleksandr studied in Kyiv Institute of National Economy (former name of Kyiv National Economy University — ed.), where there was no military training department, which is why he was called up for military service right after graduation. Oleksandr was deployed to the Southern force command in Budapest. He worked as a record clerk in the financial department of the group headquarters. Later, he was designated as a warrant officer:

— It surprised me that unspent money, to be more precise 980 thousand rubles, were returned to the Ministry of Defense budget. The following year I returned 20. After that, in the headquarters of Odesa division where I served for 8 years, I returned 18 rubles. Although I was wearing the warrant officer uniform, I maintained good relationships with the officers, generals, and commanding. There was mutual respect.

In 90s, to provide for the family, Palariiev was dealing in trade, carrying the well-know chequered-bags (bags for carrying goods, which were popular with market salesmen in the Soviet times — tr.n.) to Poland, Yugoslavia, and Romania. Afterwards, he worked on a farm, where he acquired the skills in building. Oleksandr pointed out that he had always tried to do his best when working for someone else. His wife told that from 1992 to 1997, because of his heavy workload, Oleksandr couldn’t even celebrate the birthday with his family, neither his own nor that of his wife or sons.

When business is a hobby

Oleksandr claims that Frumushyka-Nova is a business rather than a hobby. If business is not profitable, it is bound to fail:

— What if something happens and I pass away, who will keep the pot boiling? Let’s suppose people will remember about it for a year or two, but then the boys will have to put their efforts into it to earn money.

Oleksandr was strict with his sons.

— I did not teach them — I punished them. My wife would always cry when I reprimanded them, but I suppose now they understand what it was all about.

Oleksandr kept his children around and encouraged them to start their own business. Now, his sons live around Odesa and Frumushyka-Nova. Both of them manage their business in Odesa. Mykhailo oversees the showroom of fur goods. Each year, he and his wife go to Spain, China, and Singapore, buy fur clothes and produce similar models in Germany. The eldest son, Volodymyr, owns a chain of restaurants.

In Frumushyka, the Palariievs produce wine. They have set up a wine cellar, where different kinds of wine are left to mature. Aligote is the most popular choice there.

— It is not enough just to build a wine cellar: it requires maintenance. It is the same as to conceive and to raise a child.

slideshow

The first toast is always proposed to Frumushyka, the second to Frumusyka’s builders and the third — to their guests.

The Palariievs are not going to settle down with what has already been achieved:

— We want to build additional buildings to accommodate another 200 people. These are going to be not hotels but guesthouses, loggias, bungalows, like the ones in Southern Africa, Namibia. There also will be a couple of “smart houses” made of eco-materials with a heat pumps, solar panels and automatic equipment so that people could feel comfortable. These would be the houses for groups of people who want to have rest together.

The museum of the Soviet past

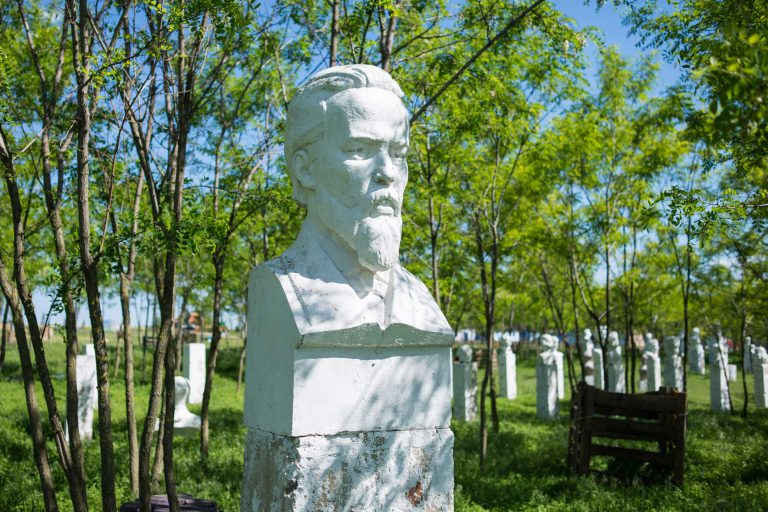

In Frumushyka-Nova, there is another unique tourist attraction — an open-air museum of socialist realism. Over a hundred statues of Soviet leaders, namely Lenin, Brezhnev, Stalin, Chkalov, Kirov, and Chapaiev, captured in their famous stanzas, are scattered on the moor, meeting every sunrise and following sunsets that offer stunning views in this area.

Busts and full-size statues are not fenced with barbwire, on the contrary to Grutas Park near the Lithuanian town Druskininkai. However, it was the museum that gave Oleksandr Palariiev an idea to do something similar in Ukraine. In 2010, Oleksandr visited Lithuania and was inspired by the private initiative of Viliumas Malinauskas — local entrepreneur — whose open-air museum serves as a reminder of the Soviet realties to the residents of Lithuania and its visitors. The area of about 20 ha encompass the monuments not only to Lenin and Dzerzhynskyi but also to Lithuanian communist Mizkavichius-Kapsukas, military leaders Baltushis-Zhemaitis, Uborevych and Lithuanian and Soviet conspirator Mariia Melnykaite. Besides 86 pedestals and busts which were exhibited throughout 90s, Grutas boasts a collection of agitation posters, flags and military machinery. On those premises, one can also find watchtowers — symbols of GULAG and Siberia (soviet labor camps).

slideshow

After the demise of Soviet Union, museums of the same type appeared in Hungary and Bulgaria. In Budapest, there is such open-air museum called “Memento”, designed by the architect Akosh Eleed who was awarded for winning the contest of Budapest General Assembly. Talking about the total number, park with the area of 2, 5 ha encompasses 42 exhibits that represent Hungarian communist era, among which there are not only monuments of proletarian leaders but also Hungarian communists, such as Bela Kun, Endre Sagvari and Arpad Sakashyts.

In Sofia, monuments of the Soviet era are collected in the historical site encompassing a park, an art gallery and a video room. The park as large as 7, 5 thousand square meters contains a collection of 77 statues and busts of Soviet and Bulgarian communists. In compliance with the traditions, the leaders are accompanied with the proletariat and the army. Other statues represent laborers and members of kolhosp (collective farm), guerrillas and the red army.

slideshow

At first, the Palariievs had to search for exhibits on their own. Plenty of statues were left unattended on the abandoned factories:

— Removing it (the statue — ed.) away requires money. One needs to rent a car and a hoisting crane to demount it, or employ someone who will demolish it with an electric hammer drill. Now people know about our museum. They just call and say, “We have a Lenin monument. Come and get it.” Some time ago, when no one cared for those monuments removal, we even paid money to take them. A meter of the monument cost 700 hryvnias.

The largest Lenin monument was brought from Kulikovo field.

— Not all people approved the dismounting, — thus Mykhailo explains why there are red paint spots on the leaders’ grey coat. It was fixed with german glue, so it took a long time to tear it off.

With the purpose of preserving the memory about villages that were destroyed due to the battlefield building, the Palariievs initiated the exhibition of missiles found on the premises:

— We did it for people to remember what was happening on this area in 60s. It is for this pile of rusted missiles that the villages were destroyed. They would tie a cord to the military machinery and pull down houses, — tells Mykhailo.

A dried out tree, cut on each side with missile splinters, serves as another reminder of the Soviet heritage. During their first five years of living in Frumushyka, the Palariievs would always get a flat tyre when driving a car across the territory dotted with those deadly splinters. As Mykhailo told, there still is an abundance of those splinters scattered across the battlefield.

— When walking on the moors nearby, you will find plenty of unexploded missiles, which are particularly obvious at the end of winder. The earth resists the metal.

The Ministry of Defense of Ukraine has made a resolution to take over the part of this area. They have plowed up 1700 ha of “Tarutynskyi Step” State Landscape Protected Area. This area obtained such status from the local authorities. The Bessarabian moor has been saved from further devastation by Ivan Rusieev who is acting on behalf of the head of “Tuzlovski Lymany” National Natural Park. The Palariievs who have already managed to create a small oasis amid the wild moor are ready to have legal proceedings for these area with the Ministry.

— It is not about money we have invested. You can easily forget about it. These are 11 years of my father’s life which he has devoted to Frumushyka that truly matter.