Gagauzes are an Orthodox Christian Turkic-speaking people, the descendants of the nomadic Oghuz tribes. The Ukrainian Gagauzes have been compactly residing in the villages and cities of Bessarabia (Budzhak). The Gagauz culture, traditions, and cuisine have changed since the adoption of Christianity. Nowadays the tradition of celebrating one of the principal holidays of the Gagauz people, Hederlez or Saint George’s Day, is combining pagan, Muslim, and Christian elements.

Vynohradivka is a village in Bessarabia, which was founded by the Gagauzes and Bulgarians in the early 19th century. The village was unofficially divided into the Bulgarian and the Gagauz parts. The founders of Vynohradivka (the old name of the village was Kurçu) came from the villages Akbiri and Balchik in Bulgaria. According to the legend now told by the locals, when Gagauzes and Bulgarians came to this land, they first let their lambs out to graze. They decided to settle down where the lambs found food.

Nowadays the people of Vynohradivka actively support and develop the Gagauz culture and learn their mother tongue. The Ministry of Education and Science of Ukraine supports publication of textbooks for the local children to learn the Gagauz language. Besides, the Regional Centre of Gagauz culture and a museum were founded in Vynohradivka. Author of the first textbooks, as well as director of the Сultural Сentre, is Olga Kulaksyz.

From the ancient times, the Gagauz calendar had an unusual feature: it roughly divided the year into two periods — summer and winter. Each began with one of the biggest Gagauz holidays: Hederlez and Kasım. This division is associated with sheep farming, which has been the main activity of these people for centuries. Summertime began with the Hederlez holiday when the herd owners made an agreement with the shepherds and handed the herds over to them for grazing. When the time came to return the herds, it signified the beginning of the winter period. These holidays are shared by many Turkic peoples. The holidays got religious context later, after Gagauzes adopted Christianity.

The Gagauz Hederlez

Hederlez — is the holiday of the world’s revival, the first dew, the first offspring. It is one of the most honoured holidays for all Turkic peoples. The Orthodox Christian Gagauzes call this holiday Saint George’s Day and honour it as much as Easter. Time and ways of celebration slightly vary for the different peoples. Crimean Tatars, for example, celebrate Hederlez on the first Friday of May, while for the Gagauzes it’s on the 6th of May.

Hederlez

Ay Yorgi — Saint George’s DayIn Muslim tradition, this holiday is associated with a meeting of Islamic prophets Illia (Ilyas) and al-Khidr (Khedher) on earth. Ilyas, who is believed to be the patron of water and cattle, comes from the West. Khedher, in turn, comes from the East and is the patron of humans. Names of the two prophets are combined in the name of the holiday. The first day of Hederlez celebration is the day when they meet, which the Turkic people believe to be on the first week of May.

In Vynohradivka, Hederlez is celebrated on the 6th of May. On this day, they typically cook kurban, the meat of a sacrificed lamb; kurban bulguru (pirinci), porridge made of bulgur or rice; and kurban ekmiaia, bread. The word “kurban”itself means “sacrifice”.

An important part of the holiday in Vynohradivka is preparing a dish called kurban bulguru. A whole carcass of a lamb is being donated to the head of the local church. Villagers believe that this brings welfare, peace and health to families in the next year.

Everyone in the village is invited for the celebration. Anybody can engage in organization of the festivities:

— Who wants can contribute a sacrificed lamb. Such a donation is believed to bring good health. When there is no lamb in a household, it can as well be bought.

Villages with churches named after Saint George celebrate the Temple Day (the Day of the Village) on this day. The church in Vynohradivka is actually named after Saint George, so the tradition is well-kept.

If newlyweds have chosen Saint George as the protector of their family, or head of the family’s name is George, then this holiday is celebrated in family circle.

Celebration can be divided into two stages: religious and entertaining. In the morning, villagers go to church for the holy service, after which they gather for holiday dinner and festivities.

If Hederlez falls on one of fasting days, like Friday, then the meal will consist of lean dishes only. Fish soup, boiled and fried fish, pickled herring will be served instead of meat.

After the dinner, it’s time for festivities. In the past, horse races, sport competitions, and wrestling were traditionally held. Now the format has changed a little, as Olga Kulaksyz says:

— In Vynohradivka we have no proper area to hold a horse race, even though we do have horses. We conduct sport games possible to organise: checkers, chess, football, wrestling. Wrestling is very popular in our region. And the indispensable part is the concert.

Musicians from other villages of Bessarabia and Gagauzia are invited to perform.

Saint George’s Day is also celebrated by the Bulgarians of Vynohradivka. For the holiday, all those who once left the village come back home. Some celebration customs for this holiday are different for Gagauzes and Bulgarians. However, there are more similarities.

slideshow

People put tables outside and invite everybody to share the meal, even the passengers of a bus which might stop nearby. Joy this big has to be shared, as Olga tells:

— It is a day of a blessing. People are happy to have such a holiday, to celebrate the life going on.

Gagauzes have a legend to explain how the Saint George holiday tradition started. Once upon a time a poor shepherd lived. He had a big family, but did not own much: six sheep and a small plot of land. One year the winter was long, he was running out of forage for the sheep, so the shepherd was looking forward to the spring desperately.

At the end of April, he took his herd out for grazing. But another misfortune was awaiting the shepherd: the wolves! He knelt and prayed so that the Lord protects his herd from the wolves. And a rider came down from the sky and told the wolves to stay away from the herd and only come out in the fields after the first snow. The wolves obeyed and retreated.

The shepherd thanked the stranger and asked his name. He replied that his name was George and promised to help all shepherds, defend grazelands from droughts and wolves. And to express gratitude in return, the shepherd was to sacrifice one lamb the following year. The shepherd’s wife was to cook pilau of that lamb and feed the poor.

From that day on, Gagauzes honour Saint George and celebrate the holiday of Hederlez.

Preparation of the dishes

On the day before the celebration people bring a lamb carcass for cooking kurban bulguru to the church. At the same time they clean and decorate the territory near the church, bring out long tables. In the evening the holy service is held and the meal for all those who helped prepare for the holiday is served afterwards.

The crucial thing, as Olga Kulaksyz emphasises, is to cook kurban bulguru:

— “Kurban” stands for meat, the meat of a roasted lamb, and “bulguru” is because that’s how we call wheat groats.

The meat and the internals of the lamb (liver, bowels) are boiled and cut into small pieces, and mixed with the wheat groats, then spices are added. Traditional spices for kurban bulgur are salt, black pepper, bay leaf, and mint. Some rice and onion is added to wheat, as it makes the taste softer. Then water and oil in the proportion of one litre of sunflower oil and around two and a half litres of water for two kilograms of groats are added. Semi (the name of the dish where it is cooked) is then wrapped in tinfoil and left to bake for two and a half hours:

— They don’t measure the water precisely when they add it. After they’ve added water, they take a wooden spoon used to stir, and put it vertically in the dish. If the spoon is standing, then the amount of water is right.

Kurban bulguru is not a dish cooked exclusively for Hederlez. It is also served for Christmas, and Easter, and any other time simply to please the guests.

— Sometimes we do not even wait for a special occasion. When the question is what we shall cook — the answer is kurban bulguru!

slideshow

Sarma is another dish for the guests. Minced meat and spices are added to boiled rice, and then fried on an open fire together with onions and carrots. Then wrapped in cabbage or grape leaves, put in broth and kept on a small fire for around an hour.

In the open oven near the church the kartofli mancası is cooked. For this dish, potato is cut and put in a pan. Then chopped meat, spices, onions, and carrots are added, and the dish is seasoned with a sauce that gives it a special flavour and red colour. The sauce is prepared in autumn: red pepper is boiled for a long time, minced and stewed in an oven.

Sıcak kaurma, stewed meat of a young lamb, is served beside the main dishes. Meat is soaked in vegetable oil with sweet pepper and tomato, then stewed on a small fire for an hour and a half. A piece of metal with holes is placed onto the bottom of a cauldron so that the meat doesn’t stick. The ingredients are put in layers: mutton, sauce with spices, onion cut in large rings. At a festive dinner the dish is put on a plate along with kurban bulguru and the potato.

The mixup of traditions

On Saint George’s Day, women used to go to the well to try and get some water the earliest they could and wash their faces with it to be healthy and beautiful. They also washed their faces with the morning dew.

On this day it is also common to measure height and weight of children to see how much they have grown in a year. After the 6th of May, it was a good time to lay the foundation of a house. Young men were allowed to get engaged and couples started to prepare for a wedding. The owners would hand over their herds to shepherds for grazing until Saint Dmytro’s Day, the Kasım holiday, on the 8th of November.

Families whose patron is Saint George sacrifice a lamb and cook kurban bulguru. They treat their neighbours with the dish. The leftovers from the treating are put on a table and the family continues to celebrate. In the past, people had a tradition to draw crosses on children’s foreheads with the blood of a sacrificed lamb so that they grow beautiful and healthy.

In the last few decades, the way of celebrating Hederlez changed. During the Soviet times, it was celebrated only in close family circle. Religious holidays were banned altogether, not to mention celebrating them publicly. Only in the 1980s did celebrations gain a larger scale.

There was also a period in history of Vynohradivka when Hederlez was celebrated together with a neighbouring village Dmytrivka. Today’s way of celebration was formed only within the last decade, having become better-organised and more popular.

The Gagauz people

According to the Encyclopedia of Ukraine, Gagauzes moved to southern Bessarabia from the north-east of Bulgaria and Dobrudzha in the late 18th and early 19th century due to oppression of the Christian Orthodox people of the Balkans by the Turks. Starting from the 6th century they had been migrating to Bulgaria from the foothills of the Altai Mountains.

There are two explanations for the origin of the Gagauz people. The first one claims them as Christian Orthodox Slavs who borrowed the Turkic language and traditions. According to the second one, they are Turkic-speaking Cumans, Oghuzes, who came to the land between the rivers Prut and Dnister from the Balkans.

Nowadays, the majority of Gagauzes reside in the south of Moldova and in Ukraine. Bulgaria and Romania also have a Gagauz diaspora.

According to the results of the national census held in 2001, around 32 thousand Gagauzes live in Ukraine. Most of them compactly reside in Bessarabia, namely in Izmail, Reni, Kiliia, and Bolhrad district of Odesa region. There are also Gagauz settlements in Zaporizhzhia, Mykolaiv, and Donetsk region.

Culture and daily life

The evolution of culture and daily life of Gagauzes is based on the intertwining of the traditional Balkan and local crafts. Gagauzes are still engaged in such traditional activities as arable farming, gardening, winegrowing, sheep farming, silk farming, weaving, tailoring, carpentry, leather-making, jewellery-making.

In the early 19th century, Gagauzes used to live in traditional pit houses, called bordey. Later, as the dwelling improved, they started building clay huts, called ev. Near the end of the century, the construction got a foundation. Later, following the preserved Balkan tradition and under the influence of the Mennonites (one of the Christian church communities – ed.), Gagauzes began building long houses where the side wall was decorated and overlooked the street.

Inside, the building comprised two or three rooms: a warm passage (hayat) and one or two rooms (soba, oda, içer). For a long time Gagauzes kept the Balkan tradition where the warm hayat was the centre of the house, with a fireplace (ateşlik), and a mouth of the oven for cooking. In the 1920s, open fire was almost completely replaced with a boiler, and hayat turned into a kitchen.

Consequently, one more drawing room was added to the house. The new room (büük ev, büük soba) was typically located on the opposite side of the house. It served for special occasions, the guests were greeted there. The chest (sandık)with the clothes and trousseau for the daughter was also kept there. On the walls they used to hang the festive clothes of the family, covered with an embroidered coverlet (fistan, çarşaf). Büük ev was decorated with carpets (pali, kadreli) and rushnyky (peşkir), ritual embroidered cloths.

The Gagauz carpets vary by ornament, colour, length, and width. One of the types of the Gagauz carpets is tülü pala. The ornament on the carpet is composed of repeated geometric elements.

On another type of a carpet, kırma pala, wide stripes take turns with the ornament. The name derives from the word “kırma” which means “to break”. It looks like the thread was “broken” to start the ornament after the wide stripe. The artisan put aside the main colour threads, broke the line, took a new colour and continued work with threads of another colour.

If the artisan is weaving zig zags, it’s called yolcu, and if between the wide single-colour stripes you find floral patterns, it’s koraf arası. Traditionally, carpets depicted rich flora surrounding Gagauzes: roses, tulips, cornflowers, and many others. Yet the most common ones were the bouquets of roses that symbolize the principal crafts of Gagauzes.

— The carpets are made in one technique, but their beauty is in the rich variation of patterns, colours, and sizes.

The main peculiarity of a Gagauz hut’s interior is a wide – sometimes as wide as half of the hut itself – platform made of ground or clay (pat dolma) between the side wall and the back wall as an extension of the oven’s body. They slept there by night and worked during the day.

Traditional Gagauz furniture included a low round table (sofra); a wooden bench (skemnä); immobile narrow benches (küçük pat), which in the second half of the 19th century were replaced with tall tables (masa) due to the influence of the city culture; long mobile benches with a backrest and armrests (skaun); wooden carved beds (krivat); cupboards and wall cabinets (dolap).

Several generations lived under one roof. It was a common rule that the youngest son stayed home after marriage to take care of his parents. Wherever he went, he was obliged to return to take care of the elderly parents.

When a girl was born, they would put a crochet hook or scissors underneath her pillow so that she becomes an artisan as she grows up. As soon as the girl was able to hold a needle in her fingers, she was taught to embroider or knit. That was the moment when she started preparing trousseau for herself. She was to embroider rushnyky for her future husband, godparents and brother-in-law. The brother-in-law was the helper of the godparents and accompanied the bride and groom throughout their wedding.

Weddings were huge: the number of guests reached three hundred. They were seated along the long tables. Benches, custom made for this event, were covered with carpets.

Even today, there still are girls who prepare trousseau for themselves. But they no longer embroider rushnyky on homemade canvass. The weddings too have become less numerous and more modern.

Vytynanka (cutting) on fabric was used to make coverlets. When the newlyweds would go to visit their godparents for Easter or another holiday, they were to bring a korovai, a traditional bread. They were also supposed to put apples, cookies, sweets, and a boiled chicken on top of the korovai. For the food not to fall down, they would tie it in a cloth and cover with vytynanka. Gagauzes also made coverlets for pillows, curtains and drapes with vytynanka.

Оlga

Olga Kulaksyz was born in Moldova, in the village Dezghingea, graduated from pedagogical vocational school in Cahul. She still remembers her first visit to Ukraine: students were awarded a trip to Izmail for their good work at a subbotnik, voluntary-compulsory work on the weekend in soviet time.

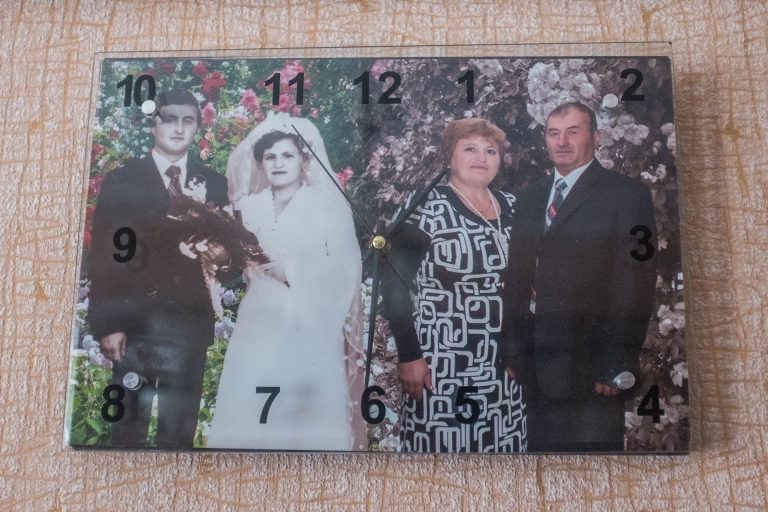

Olga had teaching practice in the city Vulcănești where she met her future husband. Soon after that they got married and moved to Vynohradivka in 1982.

Olga felt homesick at first, because love to her homeland is forever in her heart. But now, she says her homeland is rather a place of power where she can charge with energy for daily work. When everyday troubles upset her, Olga goes to visit her homeland and simply have a rest.

slideshow

Vynohradivka has become her second homeland:

— My homeland now is where my family and children are, I live and work here, the state takes care of me. Ukraine is my homeland.

According to Olga, the Gagauzes of Vynohradivka are more proud than the Gagauzes of Moldova. This might be associated with the desire of the local Gagauzes to stand out among other ethnic groups.

However, as Olga says, in Vynohradivka Gagauzes and Ukrainians live peacefully next to each other and easily find a common language.

— In our village there are Ukrainians, they speak Ukrainian, we speak Russian. And we understand each other. There is no obstacle. We share seeds, recipes for some dishes. When somebody cooked something tasty, we share and treat each other.

For almost 40 years already, Olga Kulaksyz has been developing the Gagauz culture. At first she taught the Gagauz language at the local school, compiled course books and textbooks approved and supported by the Ministry of Education, and then she became the director of the Regional Centre of Gagauz Culture:

— Every new type of activity I do places more responsibility on me. Yes, I feel sadness. But this responsibility, that it has to exist, and on this background, sadness and grief step back, only responsibility stays.

The Cultural Centre

In 2015, the Regional Gagauz Culture Centre was founded in Vynohradivka. Workshops in a variety of crafts are held here. Every year on the 17th of December, the Handicraft Day to honour Saint Varvara, the patron of artisans, is organized in the Centre. The event aims to raise awareness of Gagauz traditional crafts. Also, workshops in weaving and crocheting were held. Classes of modern arts such as making pictures of satin ribbons, string art, and quilling took place too.

— Gagauzes engage in activities that bring pleasure and joy.

The premises of the Centre also accommodate a museum where one can get to know the culture and lifestyle of Gagauzes. They have old family photos, a loom, carpets, rushnyky, vytynanky, tablecloths, and a collection of national clothes.

It was no easy task to gather exhibits for the museum. At some time Vynohradivka already had a similar museum, but it was closed because many of the exhibits were lost due to lack of proper care.

There was a time when museums of Bulgaria and Romania were gathering antique things from private collections. Many locals gave or sold what they had. Thus, not much was left for the Centre. Now the exhibits they have are called sedef, gems.

— Culture has no nationality. All this beauty was passed on from a craftsman to a craftsman.

The Centre represents not only the Gagauzes of Vynohradivka, but also the Gagauzes from other villages of Bessarabia. Traditions, daily life, cuisine, and language of Gagauzes varies depending on where they live. The environment affects everything. They are trying to show this variety in the Centre. For example, the villages Dmytrivka and Oleksandrivka lie close to the Bulgarian villages, so one can hear Bulgarian words in their speech:

— Everybody has some interesting peculiarities, they are all different. Even by some words, you can understand that this man comes from Kotlovyna, and this one comes from Oleksandrivka, and this one comes from Vynohradivka.

In 2017, Olga went to the Odesa Regional Centre for Ukrainian Culture to hold the Gagauz culture days there. At the exhibition, they presented, among others, the traditional folk art pieces. The visitors found a lot in common between the Ukrainian and the Gagauz ornaments:

— The Ukrainians saw embroideries which their grandmothers have at home, they saw vytynanky with the same patterns. You know what the artisans did? They used to go to another village — a Gagauz or a Ukrainian one — and borrow patterns and samples from there to create their own embroidery.

Holidays

The Cultural Centre is reviving the Gagauz national holidays. In the same manner, on such a large scale as Hederlez in Vynohradivka Saint Dmytro’s Day, Easter, Lazarus Saturday, Christmas are celebrated.

The volunteers were taught to sing traditional songs, they added musical instruments for the Christmas vertep, including bayan and accordion.

Lazarus Saturday is celebrated on the day before Palm Sunday. 7-9-year-old girls go from house to house and sing a song about Lazarus. House owners give them flour, butter, eggs, sugar, sweets, and money in return. Then the girls put all that into baskets and take it home, and their mothers use the products when making dough for the traditional Easter bread, paska.

— We at the Centre have been doing that for three years in a row. People are waiting for us, they invite us to come to their homes. We have gathered a group of kids, and they bring their friends every year. We sing songs and wear national costumes.

Another holiday that is being revived by the Centre is called Suvraka. It resembles the Ukrainian Malanka holiday. On the Old New Year’s Eve, the Orthodox New Year informally celebrated on the 14th of January, children take a twig of a fruit tree, decorate it with colourful tinsel, walk from house to house, and lightly hit the host with the twig as they wish them a happy New Year.

— There is a mask of a goat that is worn by one of the carollers. And each host tries to tear off a piece of that mask, as a sign of prosperity for family for the coming year.

The 1st of March is the Spring Meeting Day. Gagauzes congratulate each other on the arrival of spring and give each other a martêcık, a small crocheted flower, a symbol of spring. They hang it on a tree and do not take it off for a whole month so that the tree grows well. Every year the employees of the Centre crochet dozens and even hundreds of martêcıks and give them to the villagers:

— The first time we made, I believe, 60 flowers. It was not enough. Then we made 180, and last year — 300 flowers. And it’s still not enough. People are looking forward for the Gagauz Centre to give them a symbol of spring on the 1st of March.

Learning the language

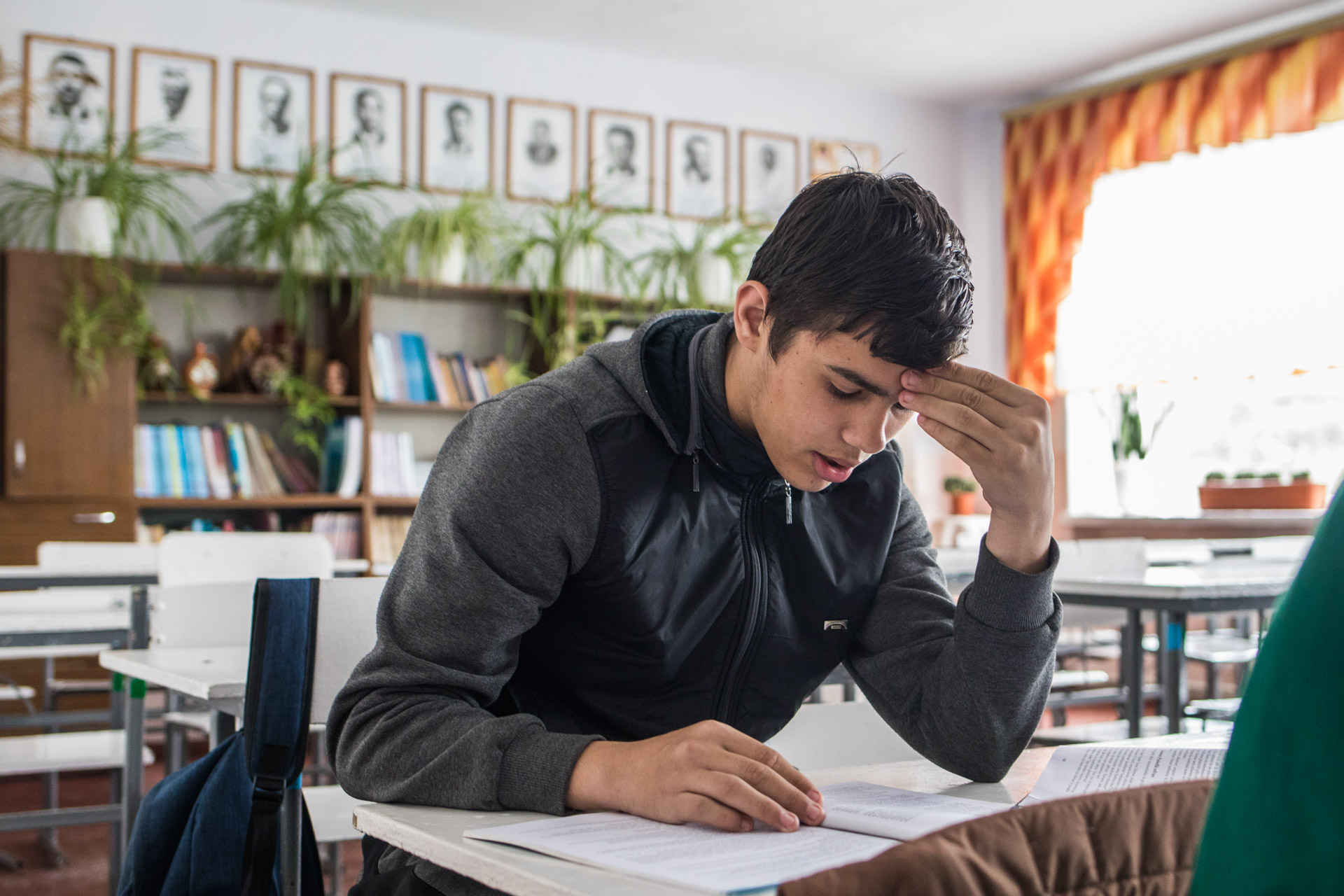

Over 400 children study in the school of Vynohradivka. They start learning the Gagauz language in their first year of primary school alongside Ukrainian, Russian, and English. When they are in their fifth year, some students continue learning Gagauz while others start learning French.

Evginiyä Kışlalı was born in Vynohradivka. She has been teaching the Gagauz language since her first day working in the school, even though she graduated from the university as a history teacher.

In Vynohradivka they began learning the Gagauz language in 1991. Olga Kulaksyz had a student whose grandmother was Gagauz and his grandfather was Ukrainian. At home, the family spoke Russian, and the boy could not do his homework. But he stayed in class, didn’t want to leave, and step by step learned the Gagauz language.

By 1995 the Gagauz language was an optional subject. But the Regional Department of Education suggested that Gagauz is studied as compulsory. All teachers agreed, as this was a great opportunity to teach students how to write in Gagauz. Children learned to speak the language, but nobody taught them how to write. Hence, the classes in Gagauz were introduced gradually. Initially, only for the first and second year primary school students, and then for the older students as well.

— Students of the eighth year who had never studied the Gagauz language before, came to our classes for the first year students and stayed to listen to what it is like to study Gagauz.

— Children enjoy classes of the Gagauz language, especially when we learn proverbs, sayings, new words, read Gagauz poets and writers, learn about the holidays and traditions of our people.

By 2006, they had been studying the Gagauz language using the textbooks published in Gagauzia of Moldova (Gagauz Yeri). Later, they started using the course books developed by a group of the teachers of Vynohradivka, and Olga Kulaksyz was among them. The teachers even included the illustrations: photographs of holiday celebrations, national clothes and daily life from their personal archives.

These course books are used to study the Gagauz language not only in Vynohradivka, but also in five other villages: Dmytrivka, Oleksandrivka, Kubey, Stari Troiany and Kotlovyna. In three other villages the Gagauz language is an optional subject. But Olga Kulaksyz hopes that in 2019-2020 academic year Gagauz will become a compulsory subject in those villages too.

Olga has compiled a textbook for reading. It is used from the first year of primary school as additional material for learning the Gagauz language:

— I thought that maybe there are Gagauzes in primary school who already know how to read, so I have collected material which can help broaden the language-learning. This is also an aid for a teacher.

The texts are telling about the way of life and traditions of Gagauzes. The topics are connected with the material in the course book for learning Gagauz. For example, if the topic is Mother’s Day, the textbook will have something about mother: a short story or a poem. The textbook also has a story about the traditional holiday of Hederlez. Last year Olga combined two of such little books and published a course book which is now used in all schools where the Gagauz language is studied. Publishing of the book was funded from the budget.

The school is still receiving additional materials from Gagauz Yeri, who supply fiction, historical literature, books about holidays and traditions. When learning the Gagauz language, the method of comparison is used: translation into Ukrainian and vice versa.

Olga Kulaksyz believes that one must learn the mother tongue of one’s nation, but not only that:

— Of course, they (the Gagauzes — ed.) are Ukrainians as well. But they also know their mother tongue which makes them a little bit different. One must know one’s mother tongue, as well as the language of a person living next to them, who is a friend.