Out of the 30,000 ethnic Germans who spread out in almost all regions of Ukraine between the 9th and 20th centuries, around 3,000 live in cities and villages of Zakarpattia. The German settlers in this region best preserved local German dialects, traditions, and culture, while in most of the other regions, the German descendants assimilated into local culture.

The German settlements in Zakarpattia were first mentioned in the late 12th century. Craftsmen from Lower Saxony arrived here to restore the villages and cities destroyed after the Cuman attacks as well as to build new ones. Later, in the 18th century, there were a few waves of German immigration to this region.

In 1711, Archbishop Lothar Franz von Schönborn received land and estate from Charles VI, Holy Roman emperor, after the defeat of Ferenc II Rákóczi, prince of Transylvania who led a rising against the Habsburg empire. Consequently, the Schönborn family of Bavaria began sending German craftsmen to devastated mountain villages for restoration and upkeep of the land.

The German settlements created at that time were called colonies. Zakarpattia’s land was split into dominions that consisted of cities and villages and belonged to lords, the church, and the government. Later, the counts of Schönborn of Vienna inherited the dominion and began inviting German colonists from Upper Austria. Unlike Bavarians, they focused more on farming, gardening, and growing vineyards.

The second wave of German immigration to Zakarpattia ties back to Maria Theresa, Holy Roman empress, who offered a deal to German craftsmen: families were provided with rent-free land and no obligation to pay taxes for years. The goal was to develop the salt and logging industries in sparsely populated areas. At that time, German settlers reconstructed Palanok Castle in Mukachevo and built multiple factories in Svaliava, Berehove, Hrabivnytsia, Pidhoriany, and Mukachevo. In total, thirteen villages in Zakarpattia were populated by Germans, some of which are Pavshyno, Shenborn, Nyzhnii Koropets, Verkhnii Koropets, Chynadiiovo, Kliucharky, Kuchava, Syniak, and Sofiivka.

Nowadays, despite the small number of Germans in Zakarpattia, they are socially active, learn the language and history of their ancestors, celebrate traditional German holidays, and organise festivals.

Schwalbach. Volodymyr Tsanko

After Ukraine gained independence, the first centre for German culture in Zakarpattia was created in Svaliava. Volodymyr Tsanko, an ethnic German and the founder of the community, tells his family story. His mother is an ethnic German with the surname Bauer. She was born in Bessarabia, another region in Ukraine where Germans used to settle. His father is a Ukrainian from Svaliava. Both of them were exiled to Siberia for 10 years by the Soviet government. His mother ended up there for her ethnicity, and his father was there as a prisoner of war as he served in the Hungarian army.

— They got married after the war. They met in Siberia, as they were both under political repression after the war because Mum was German and had to undergo that process.

Volodymyr’s brother and sister were born in Siberia. His mother and brother have been living in Germany for many years, but Volodymyr decided to stay in Zakarpattia.

— I love Ukraine, and my family doesn’t want to move to Germany.

Svaliava was first mentioned in the 12th century as a small settlement that belonged to a Hungarian lord, Bet-Betke. In the 18th century, it was part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire with the name Schwalbach. Later this land was passed on to Schönborn and his descendants, who developed farming in this area for over 200 years. Gradually, Svaliava became a multi-ethnic city with a significant number of Germans.

Volodymyr Tsanko and his colleagues founded the folk pop band Schwalbach, which has already received recognition on a national level. It is based on the German community in Zakarpattia.

slideshow

Volodymyr used to hear German songs as a child from his mum and from older people. As a schoolboy, he learned to play the tsymbaly (a Ukrainian musical instrument similar to hammered dulcimer. — ed.), sopilka (Ukrainian folk instrument of the flute family. — ed.), trumpet, and guitar and played in an orchestra. Later, together with a few musicians with German roots, he attempted to create a music band.

At the time, Svaliava already had a few communities, in particular Hungarians and Slovaks, so ethnic Germans decided to start their own community. Volodymyr recalls that at the time of creating the community organisation, there were about a thousand German families living in the city.

— The purpose was simple: preserving the German traditions, history, and culture through integration and enrichment. It means a lot to us, especially here in Zakarpattia, in such a multi-ethnic land.

The activists contacted the Society for Development fund in Odesa, which is financed by Germany. This charitable foundation provides assistance to German organisations in Ukraine. After some negotiations, they submitted requests and received basic music equipment. The band currently performs both German and Ukrainian songs. Volodymyr says that when they meet, the Germans from Zakarpattia mostly speak Ukrainian but still do their best to preserve German, especially amongst youth.

— We live in Ukraine. Of course, our native language is Ukrainian, but our mother tongue (Muttersprache. — ed.) is German.

The musicians learned some of the songs from their parents and collected others in the villages of Zakarpattia over three years. They went on an expedition to families in Shenborn, Pavshyno, Verkhnii Koropets, Hrabivnytsia, and Syniak. First they wrote down the lyrics and later arranged the music to adapt it to a pop format. The musicians say that, unfortunately, the number of Germans in Zakarpattia is decreasing, but the folklore achievements should be multiplied and spread.

At festivals, the band performs mostly upbeat humorous songs, such as “Lustig ist das Zigeunerleben” (“Merry Life of a Gypsy”), “Schwarzwaldmarie” (“Mary from the Black Forest”), and “Suzanna”. It used to be completely different, as the older generations sang mostly lamenting and sad songs. It was caused by years of repressions from the Soviet government that they had experienced.

slideshow

Gabriell Kmetie, a member of the band and an ethnic German, explains that such songs bring back memories from their homeland.

— They were reminiscent to those who experienced concentration camps or who missed their homeland, including Germany — the country they came from.

Gabriell’s ancestors lived on Ukrainian territory for over a century and worked in the logging industry. They also suffered for their Bavarian origin. In particular, the musician’s great-grandfather Karl Sterbau founded a woodworking factory in the village of Drachyno (Dorndorf). The Soviet government nationalised the factory in 1945, and the successful craftsman and entrepreneur with German roots was exiled to Siberia. Fortunately, the descendants of repressed Germans had a chance to return to the land that had become native to them.

Traditions of the Germans of Zakarpattia

The ethnic Germans of Zakarpattia preserve their cultural identity through traditions, customs, and celebrations. The Roman Catholic church is a uniting factor for the local residents, as that is the faith of most families.

The community gathers for Christmas carols, Easter, Whitsun, Mother’s Day. Germans often visit neighbouring villages for celebrations. The closest connection is between churches that are served by the same priest. There are two priests of German origin in Zakarpattia. Both of them are fluent in Ukrainian but they hold church services in German.

The Germans of Zakarpattia celebrate Christmas in a more Ukrainian style by observing the fast. In some way, they have adapted to Ukrainian customs. For example, they bless baskets with food at Easter, which is more characteristic of the Ukrainian tradition. An Easter symbol for Germans is a bunny that brings Easter eggs. Adults arrange Easter egg hunts in their gardens for children, hiding eggs (called Osterneier in German) and other gifts.

There is also a carnival celebration before Easter, called Fasching, similar to Mardi Gras festivities. Forty days before Easter, people dress in colourful costumes, paint their faces, and prepare to transition from this joyful celebration to a more peaceful time of Lent. Every ethnic German remembers Mother’s Day (called Muttertag in German) from childhood, when on the second Sunday of May they would go get wildflowers or come up with creative ways to celebrate their mums. Another big holiday for Germans is Kirchweih, the church anniversary.

Chynadiiovo. Valeriia Osovska

It would be quite difficult to find a settlement in Zakarpattia that was not affected by one of the Schönborn dynasty members. A few centuries ago, while under the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Chynadiiovo was called Saint Miklós (Saint Nicholas). The last count of Schönborn built splendid Beregvar Castle with vast hunting grounds close by the village. After World War II these lands were passed to collective farms, and the castle was used as the Karpaty health resort.

Valeriia Osovska, German by ethnicity, lives in Chynadiiovo and manages the regional info centre for all German organisations in the area. Her family is mixed, just like most here: her mother is Ukrainian, and her father is German. Valeriia spoke the Swabian dialect for as long as her grandparents were alive, as they barely knew any Ukrainian. Valeriia went to a school where German was a more prioritised foreign language. This motivated all kids in the area to study German: for some to preserve their roots, for others to understand their friends better. However, Valeriia and her husband still faced some teasing when back in the 70s people would joke about ‘Fritzes’.

— While my grandparents were still alive, we didn’t even know Ukrainian. We went to school and children made fun of us. It was very disheartening at times.

With time, the diversity of the Swabian dialect faded away. The children began using a more literary German language.

slideshow

Valeriia’s family also experienced repressions from the Soviet government. According to Valeriia, her husband’s ancestors were exiled to Siberia simply for their German origin.

The local club is associated with the Chynadiiovo German сommunity organisation. There is loud music as children in national costumes perform folk dances. The club is also a great location for the elderly to come together.

There is another village near Chynadiiovo with a few Ukrainian-German families. It is supposed that the mountain village Syniak was named after the blue shade of Lake Synie (Blue — tr.), which was discovered by local shepherds. The legend says that the sheep grazing next to the blue water were never sick due to the healing properties of the water. Later, a health resort was opened here. The German language in Syniak is used not only in school and in some homes but also during church services. Josef Trunk is a German priest who came here after the fall of the Soviet Union. He found out about a wooden church that was built back in Schönborn days and destroyed by the socialists. Josef found sponsors and support to build a new Roman Catholic church in its place.

German bread and a new surname. Josef Kaloj

Barbovo village near Mukachevo is known by a few names: Hungarians call it Bárdháza, Ukrainians use Borodivka or Barbovo, and Germans call it Barthaus (from German Bart — beard — and Haus — house). The locals know several legends for how the village was founded. One of them states that there used to be a house with an overgrown vine that was similar to a beard. Since then the house was called bearded. According to historical evidence, the architecture here was similar to German half-timber houses without the timber framing. The Germans of Zakarpattia mostly lived in homes with three-section planning with a side entrance into a passage or kitchen. This housing had soil flooring, an open chimney, and a straw-covered roof.

Josef Kaloj, Austrian by ethnicity, owns a bakery in Barbovo. Besides business, for many years he has been involved in the community at the Council of Germans in Ukraine, which represents the interests of ethnic Germans. Josef is a German cultural centre manager in Barbovo and also an active participant in regional informational meetups.

Josef’s ancestors settled in Barbovo during one of the massive immigration waves when Austrian and German families came to Zakarpattia to develop farming. Kaloj is not Josef’s original last name. His family was forced to change it from Köbel because of the Magyarisation policy (which is the policy of assimilation of non-Hungarians on the Austro-Hungarian Empire territories). At that time, foreign last names were forcibly changed to a Hungarian equivalent in birth certificates.

Josef used to be a farmer, but now the bakery is his life’s work. He recalls going to Germany and Austria to become more familiar with different baking techniques, which he later began using back home, in Zakarpattia.

slideshow

In the late 90s, Kaloj personally made deliveries by car and honked for customers to come out and buy freshly baked bread, all the way between Mukachevo and Barbovo.

— We started with small amounts, with only two or three oven loads per day. But later, in 1998, there was a massive flood here, and all of the local state-owned bakeries in Mukachevo were flooded. People desperately needed bread.

The ovens brought from Austria are now used to produce a thousand loaves of bread per day. The Kaloj family also tried baking Graubrot (whole grain German rye bread — tr.) but the original recipe with a big amount of herbs and spices did not become popular here. Josef says that there used to be much less competition, but now since every supermarket has its own bakery, it has become harder to stay in business.

— I still have a chance because we don’t add anything unhealthy or unnatural, no flavour enhancers.

Josef’s wife is Ukrainian, so their children were brought up in a bilingual environment. She reminisces about it being hard for her to adapt as well since she is from Halychyna and thus needed to learn the Zakarpattia dialect first and on top of that try to understand German.

Josef speaks German with his children, but everyone in the family uses Ukrainian with the grandchildren. He confesses that he barely knew any Ukrainian before going to school.

— There were a couple of Ukrainian families amongst us. Not all children spoke German. It was harder for ten of us to learn Ukrainian than for one to learn German.

Josef and his wife say that they never sought to leave Ukraine. Although their children received an education abroad, they also refused to stay there and returned home. Now, his whole family and his life’s work are here, in Zakarpattia.

1998 flood in Zakarpattia

A natural disaster of intense rains and overflowing rivers flooding almost 120 cities and villages in the region.

Julia Teips

Grüß Gott! (German for “May God bless you”) Julia Teips greets Josef. She is a journalist, German teacher, and the head of the German Youth of Zakarpattia community organisation. She met Josef at a regional gathering of ethnic Germans, and they still stay in touch. And even though Josef is Austrian and Julia is German, they still call themselves Germans, like everyone here.

When it comes to the language that local Germans speak, Julia says that every village has a specific dialect, but overall, it is considered that they all speak the Swabian dialect. The names used to describe the community and their dialect have been adopted, and the Germans of Zakarpattia still use them in everyday life. At the same time, Julia points out that they are not quite correct: the local Germans don’t speak Swabian, but a specific dialect of the German language common in Zakarpattia.

— ‘Swabians’ is the name that was used during the Austro-Hungarian Empire times to refer to all Germans who lived outside of Germany or German-speaking countries. However, there is no historical proof that ethnic Germans from Zakarpattia have anything to do with the Swabia region.

Julia’s ancestors are from the Kliucharky village, where she currently lives with her family. According to Julia’s mum, Nataliia Teips, their traditions were passed on from the older generation. They followed the religious customs, went to church, celebrated Easter and Christmas together, and taught their children and grandchildren to value their culture and language just as much. Nataliia considers German her mother tongue and Ukrainian her second native language. Julia, on the other hand, says that both are equally native to her, so much that she cannot even recall when she became bilingual.

— I think that it is certainly important to know the Ukrainian language, as it is a part of our soul, our nationality.

slideshow

Julia brings up her son in a bilingual environment, as her husband is Ukrainian. German is most often used in everyday life in attempts to preserve the authentic local dialect, so that it is not forgotten, while youth mainly study and prefer literary German (Hochdeutsch).

The German songs and prayers were passed on to Julia by her great-grandmother. As a child, she learned the Lord’s Prayer in German first.

— It was very important for ethnic Germans, the devoutness and support of language and traditions in church.

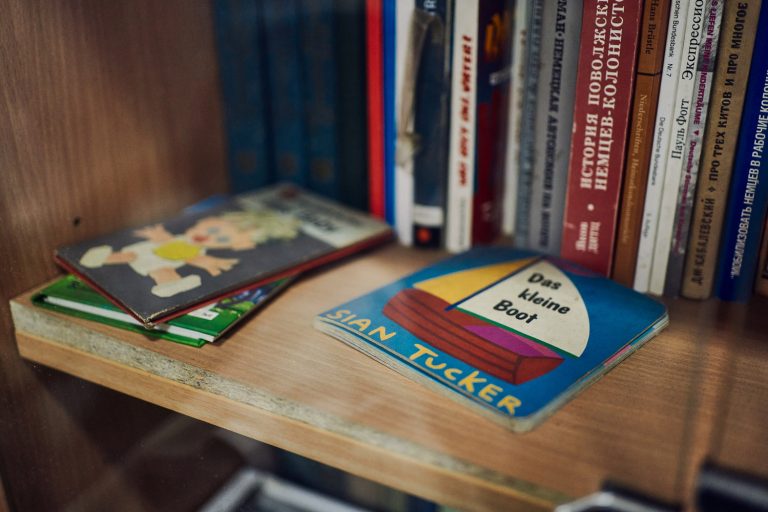

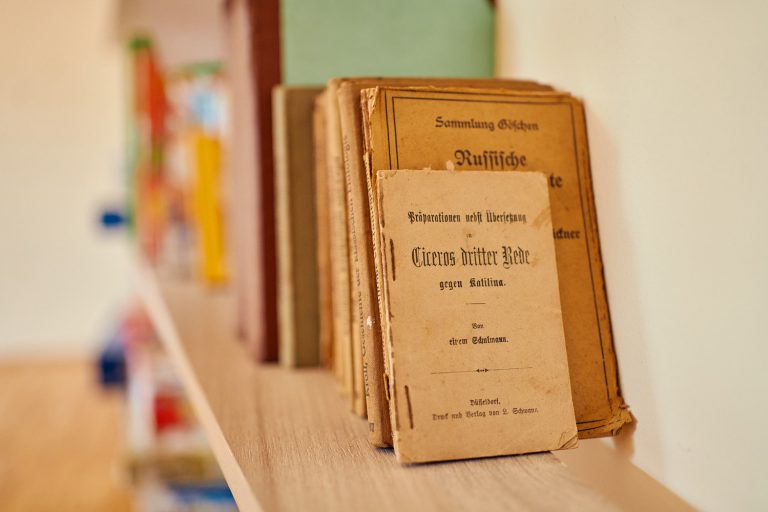

Julia opens her great-grandmother’s green German prayer book. Ethnic Germans still use many old songs and prayers during church services. “Unfortunately, a lot of German books were destroyed during the Soviet times,” Julia says. After World War II, it became extremely hard for ethnic Germans to preserve traditions and cultural identity because society as a whole changed the attitude towards their community. The Teips family knows stories of neighbours acting in a very prejudiced, condescending, and mocking way, calling them fascists or Nazis. Julia also experienced similar teasing because of her German last name, even though it was many years later.

An important period in self-realisation of Julia’s origin was when she worked as a journalist on a TV channel for a German edition. At some point, one of the viewers gave her a book that mentioned the last name Teips a lot; he suggested that it could be about Julia’s ancestors. She decided to look into it and came across the lists of repressed people from Zakarpattia and stories from different families, which helped her learn more about her genealogy.

— The book spoke of three brothers with the last name Teips who moved to Zakarpattia when the count of Schönborn owned property here. One of them was a ranger, another one worked at the railroad, and the third one was an architect, who built a part of a street in Mukachevo, as in he created the plan.

Julia was in Germany many times, studied there, received scholarships from the German government, and was an intern in television. Journalism has always been her passion. Later, she had a desire to learn more about the German movement in Zakarpattia, and not only about her ancestors. Julia decided to create a youth organisation and a training centre in Zakarpattia to encourage young people to learn more about the German culture.

Social activism

There are ten German communities in Zakarpattia, so almost every village with ethnic Germans has their own organisation. The German Youth of Zakarpattia community organisation in Mukachevo is part of the Council of Germans in Ukraine. They offer free German language classes for ethnic Germans. In particular, thanks to the cooperation with the Goethe-Institut Ukraine, the youth have an opportunity to practise with native speakers. Julia says that some people need the language to study or work in Germany, though some ethnic Germans study the language for their own pleasure. In addition to language classes, the German youth in Zakarpattia learn about the lineage of Germans and their settlements in the area, as well as German culture and traditions.

— We do all we can so that every family that considers themselves ethnic Germans remembers and has access to this information and is able to explain their genealogy.

The organisation implements local and multi-regional programs, together with two international projects that involve other organisations. Even though Julia changed her professional path, journalism is still a highly important part of her social involvement. It specifically shows in her passion for organising various projects about media literacy. One of such extremely powerful youth initiatives for ethnic Germans is a project called ‘Language, Mass Media, Nature’, which took place in the Carpathian Mountains. The youth studied German and learned more about mass media work while visiting public television, meeting well-known journalists, and preparing news reports.

slideshow

Another project, called ‘The Germans of Zakarpattia Talk Show’, was more of an expedition, where youth were introduced to the variety in local German dialects while travelling around villages and taking short interviews from people of older generations.

Together with the team, Julia has an intention of extending the organisation’s involvement in the whole region. One of the ideas they would like to implement is to have a socially active young person in every region that has a population of ethnic Germans. Such a network would make it much easier to spread the information about the Germans of Zakarpattia amongst the Germans and Austrians who come to visit Ukraine.

— It is great to have people locally who would actually be involved and be able to provide reliable information and could tell you more.

slideshow

German language classes, social programs, and cultural projects of the German community in Zakarpattia are sponsored by the German government. Once a year, elderly ethnic Germans receive a social package with groceries. On top of that, they can receive assistance when buying medicine. The youth and children of German origin are invited to summer camps where they have a chance to improve their German skills.

Julia has heard questions from her friends many times about moving to Germany, and she has all the reason to live there because of her experience. She responds that Zakarpattia is the place for her.

— I have a dream that young ethnic Germans would not emigrate to Germany but stay in Ukraine. This is our motherland, we were born here. People ask me, “What are you doing here? Go, you will have so many opportunities there!” No, I have many opportunities here, because here even the homeland helps.

The stories of resettlement and life of the ethnic German community in Zakarpattia are complicated and diverse, but all of them have something in common. Each one took place on Ukrainian land, and the modern Germans of Zakarpattia tell them in two languages — German and Ukrainian — uniting the two cultures.

— The ones who wanted to leave have already left. The rest are doing their best to live here and mostly adjusted to the surroundings. They all understand each other well and have a good life on this, so to speak, native land. No need to go far to feel like an ethnic German.