A German software developer and a founder of a Ukrainian сhurch сhoir, Martin Dietze, and a Ukrainian philologist, Nataliia Kostiak, have been living in Northern Germany, Hamburg, for almost 10 years. The couple founded the German-Ukrainian Cultural Society, within which they organise literary meetings with Ukrainian writers, exhibitions, and workshops on folk crafts promoting cultural exchange between the countries.

What can motivate a German nowadays to immerse themselves in the Ukrainian context? The IT specialist from Hamburg, Martin Dietze, began to learn Ukrainian when he was a student at the summer school of Ukrainian Catholic University in Lviv. While studying, he met a lot of interesting people, so after returning home he was inspired to continue learning Ukrainian. He purposely looked for an environment where he could listen to and practice Ukrainian more. Before leaving to study in Ukraine, Martin had already been singing in an Orthodox church choir. Afterwards, he himself founded the choir at the Ukrainian church in his hometown of Hamburg.

A Philologist and a Ukrainian culture expert Nataliia Kostiak lived in Lublin, where she defended her doctoral thesis and got a doctorate degree in philology. She was just planning to move to Prague.

Martin and Nataliia met each other for the first time in Prague, although they had started communicating online long before. They were introduced by a mutual friend, Ukrainian lawyer, Sofiia Kernychna. Sofiia was doing an internship in Hamburg when she became friends with Martin. In the beginning, Martin and Nataliia conversed in English, but quickly switched to Ukrainian. Nataliia’s teaching experience helped Martin to master the language even better:

“If you want to understand a person from another country, you should know their language. It’s because language is the source of a person’s soul and mentality.”

Nataliia. Christmas Advent and Easter bread

A native of Halychyna, Nataliia Kostiak was born in Ternopil, and her relatives are from Lemkivshchyna. After World War II they were relocated to the territory of the Soviet Union. Nataliia was related to the German-speaking environment only by the origin of her grandfather, who was born in 1900 in the days of the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

Lemkivshchyna

An area in today’s Poland, Slovakia and Ukrainian Zakarpattia, inhabited by a subethnic group — called “Lemkos”.“I had particular sentiments towards Austria because I still had the feeling that this was my historical motherland, and we were formerly part of the same state. And Germany was something else, like, I visited it for some meetings, but never planned to move there.”

Since Nataliia already had an experience of living outside Ukraine, she thought that it would be just as easy for her to adapt to living in Germany. However, farther to the West, the difference in culture and mentality was felt stronger than in Eastern Europe:

“I think it’s easy for me to adapt to everything. There [in Poland and the Czech Republic] was the same cultural space as in Ukraine. Here [in Germany] it’s different. Here you have to learn, familiarise yourself, look on. Sometimes you don’t always follow their logic.”

However, Nataliia quickly got along with the Dietze family, as Martin’s father came from the southeast of Germany, where the culture of the Lusatian Sorb community, which has Slavic roots, is widespread. Martin explains that geographical differences cause differences in the ideology of different ethnic communities. Particularly, in Southern Germany, people are more straightforward, which makes them similar to Ukrainians:

Lusatian Sorbs

An ethnic group that inhabits Southeast Germany and has Slavic roots.“Southern Germany has a little more conservative culture. And if you do something wrong there, it will be made very clear to you. Here [in the north] it doesn’t happen this way. We call it, ‘den Ball flach halten’. (This phrase in German means the desire to avoid risks and ambiguities, restrained and prudent behavior, realistic assessment of the situation. Literally: ‘keep the ball close to the ground’. — ed.).”

Nataliia and Martin maintain both German and Ukrainian traditions. On major holidays, such as Easter or Christmas, they do not go to Ukraine, because they always organise ceremonial celebrations in the church with the choir. So, Martin has to be there. Every year on Easter the couple traditionally bakes Paskas (Easter bread) and a Christmas tree appears at their home closer to the Ukrainian Christmas date, January 6. The couple mostly celebrates all holidays with two families:

“You can’t celebrate twice with the same emotional excitement. The holidays according to the Western calendar we celebrate with Martin’s parents in their house. And our [Ukrainian] holidays we celebrate in our house, privately.”

slideshow

Nataliia favours some Catholic traditions, such as Advent, four weeks of preparation for Christmas. Every Sunday one candle is lit on a wreath of Christmas tree branches, so that on December 24 four candles are lit. Another tradition, which local children adore, is the Advent calendar. From the first day of December, children open one window in the calendar every day and find their small gifts or treats.

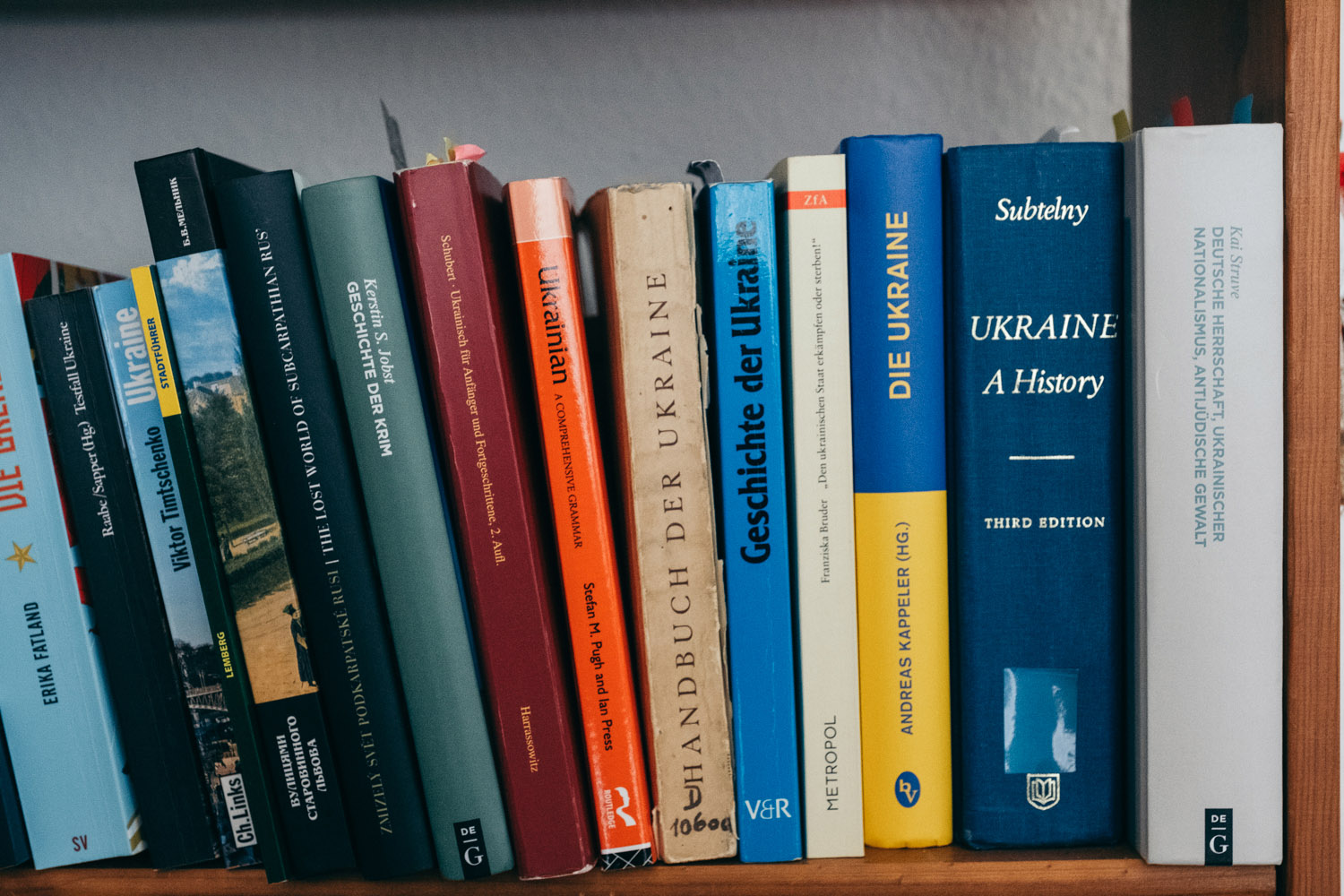

At home, Martin and Nataliia have a special room filled with everything that reminds them of Ukrainian culture: embroidered towels, icons, books, Easter eggs, family photos, and Nataliia’s and other Ukrainian artists’ paintings. Nataliia is convinced that wherever you live you can always create the atmosphere of your native land around you:

“For me, this room is a symbol, showing that Ukraine can be everywhere. We bring our cultural heritage with us, wherever we are. A Ukrainian motif prevails in this house, actually.”

Nataliia is keen on many folk crafts. She embroiders towels, shirts, and paints Easter eggs. Nataliia embroidered her wedding towel — a rushnyk — herself. For Martin, it was essential to get married in a Ukrainian embroidered shirt — a vyshyvanka.

“We got married in the Ukrainian church here in Hamburg. And Martin also was very keen that everything should be in the Ukrainian style. He said, ‘Oh, I don’t want to wear a tie, I want to wear an embroidered shirt for the wedding’.”

Nataliia adores painting Easter eggs. She learned to paint Easter eggs in childhood with her sister Halia: at that time the girls used a technique typical of Lemko traditions. From Martin’s father, Nataliia found out that a similar painting technique was used by Lusatian Sorbs. So decorated Easter eggs became a common tradition and a symbol for the couple.

Martin. Ukrainian church choir

From a young age, Martin sang and played in various musical bands. In 2010, he found a Ukrainian church in Hamburg, offered to create a real church choir there, and led it. This German recalls his first experience of conducting in a choir:

“I came to my music teacher and told him, ‘You know, I have a choir now. I don’t know what to do with my hands’. Then he told me, ‘No problem, I’ll show you’. We practiced conducting every first half of our lessons and sang the second half. That is how I prepared my first ‘Cherubim Hymn there (a liturgical hymn).”

Martin’s programming experience comes in handy every time he has to compose musical accompaniment for a church hymn. Martin creates the arrangements for it himself, transferring the text into a score by the LilyPond music editor.

“I, indeed, program music. There is a [programming] language I use to write all the notes and texts. And the program just converts those notes into media files.”

slideshow

Now at different times from 12 to 16 participants sing in the choir. Their number is constantly changing, as not everyone has an opportunity to regularly attend rehearsals and worship services. Young singers spend time with their families, or after a while they move to other cities; and the older generation needs to have a rest from time to time, to recover. Furthermore, due to the global coronavirus pandemic, it has become difficult to predict the course of events and make plans, explains Martin:

“Even before the pandemic, we knew that we needed to find new people. And particularly because if we always sing the same way, people get tired of it. Therefore, we need to grow. And this is also important to me, for sure.”

The pandemic significantly slowed down the usual course of life and the life of the choir in particular. For example, this year’s Easter celebration was considerably different from a traditional one. We had to give up on the usual liturgy and ultimately listen to the Easter service online.

“I had some things to do. And as for Martin, every year at the same time, as I bake, and everything smells here, he prepares all that Easter singing. And now this work was gone, so he was so upset.”

Martin and the choir didn’t stay away during the 2014 Ukrainian Revolution of Dignity. Nataliia remembers that the entire Ukrainian community in Germany watched the events on the Maidan at that time.

“When people were shot there, it was real, and you were sitting here and didn’t know what to do. And then I somehow remembered what I found on the Internet: Maryana Sadovska in Cologne, at the church, had been organising something. I said to Martin that we needed to do something like this here because it’s madness. When you just sit here, you do nothing, you have no influence on anything.”

Online broadcasts hadn’t been turned off at home, and as the bloodiest days came, the couple asked St. Peter’s Church in Hamburg to organise a service for the dead.

“The prayer was very good. I think that maybe it was the best thing we did at that moment. And there came the Germans and the Ukrainians — people of different confessions, not only Greek Catholics but Orthodox and all the others. Even the non-religious. They said they had experienced some kind of catharsis.”

Martin thinks of that time with no less pain:

“I cried at work because I was watching that stream the whole time. It was just a live stream, and no one controlled what was shown there. You work and at the same time you see people dying. It was just such a shock.”

Cultural diplomacy and stereotypes

About 138,000 Ukrainians live in Germany today. Nataliia tells that the Ukrainian Scout Organisation “Plast”, the Union of Ukrainian Youth, the Association of Ukrainian Organisations in Germany (AUOG) and several other local associations actively function here:

“We have several Ukrainian associations, and each has chosen its specific area of work, so we do not have a big one, but there are more of such very close-knit teams that cooperate. For example, someone sends humanitarian aid or volunteers take care of the wounded, who were treated here. And then we find some areas of overlap and help.”

In 2015, Nataliia and Martin founded the German-Ukrainian Cultural Society to deepen cultural exchange between the two countries and present the Ukrainian cultural heritage. Nataliia constantly holds master classes in Easter egg painting, making traditional rag dolls — a motanka, — and gathers local Ukrainian women to sing together and prepare some dishes:

“We also had a tradition of singing. Our Mira Frankevych decided to organize us to sing popular Ukrainian songs, which are sung at home or weddings, or elsewhere. Mira is a scout from Plast, originally from Munich, and she knows those songs from childhood. Mainly girls came to sing. After work we just gathered and had some tea or coffee. Then we also sang and talked, painted Easter eggs and made rag dolls, those kinds of things. We shared recipes and cooked too.”

Nataliia emphasises that not only the Ukrainian diaspora is interested in such classes:

“We held them in different locations and German acquaintances usually came, as well as people of other nationalities. It could be someone’s friend, girlfriend or boyfriend, who wanted to learn or to try it.”

The church choir has also become a link between different cultures. As it turned out, not only Martin favours carols created by Ukrainian composers, such as Kyrylo Stetsenko and Mykola Leontovych, but also many Germans do. And when the choir has an opportunity to perform in a German church, the Germans join to perform Ukrainian carols. About one such case, Martin says:

“I love Ukrainian carols, especially composers’ arrangements, for example, Stetsenko. And then we created a community with the idea to sing those carols together with the Germans, like a small choir for four voices. We did it for the first time, and there were a lot of Germans singing in the choir of the Russian church, and they were very open. It was so interesting for them. Last year we did it for the third time. But it was even more amazing because there was an opportunity to perform in a big church with other choirs. We met with Germans and Ukrainians; there were singers from our choir, and there were different German singers. Then we prepared a short program. It was particularly important for us to sing ‘Shchedryk’, because it is the most famous Ukrainian song, and ordinary [Germans] do not know that it is a Ukrainian song.”

The Ukrainian Consulate in Hamburg actively supports the cultural events held by Martin and Nataliia together with the Ukrainian community. They did likewise with her initiative to arrange an art exhibition of the wounded Marine from Volnovakha in the East of Ukraine, Vadym Nikolaiev, in December 2019. At that time Nikolaiev was receiving medical treatment in Germany:

“We put on a great exhibition. At that time, a bandura musician, Roman Antoniuk, from Lviv was staying in Hamburg. When he heard about this exhibition, he said, ‘I want to play at that exhibition’. We had such a festival, with a lot of positive emotions!”

After the 2014 Revolution of Dignity, Ukraine appeared in the spotlight all over Europe. According to opinion polls in 2015, more than half of Germans associated Ukraine first with the war, then with Russia, and then with the Klitschko brothers and poverty. But sadly, Ukraine’s cultural achievements remained in the shadows. For example, Dmytro Bortnianskyi is known in German society as a Russian composer, not a Ukrainian one. That is why Nataliia and Martin, resorting to the cultural heritage and traditions of Ukraine, strive to maintain its positive image and show how it can be interesting to Europe. Martin emphasises:

“This is a sample of cultural diplomacy, because we can show ordinary Germans the real face of Ukraine that is not political. That’s not what people see there in the news, but it’s just pure Ukrainian culture.”

Stereotypes about Ukraine and its past are strongly ingrained in the minds of Germans.

“Martin’s and my parents are almost the same age. We are one generation, and we are constantly comparing two stories: what life behind the Iron Curtain looked like and what life in the free world looked like, even on such simple day-to-day questions.”

When the Soviet Union collapsed, Russia became a synonym to it in the world, and other nationalities and countries were more or less not perceived as independent full-fledged entities at all. Many Germans did not even know that Ukraine has its own language, says Nataliia:

“Once Martin brought [for a master class] scores written in Latin but with Ukrainian phonetics. Holding the Ukrainian text of the carol in their arms, [the Germans] already noticed that it is a completely different language, not Russian. It happens very often and needs explanations.”

Owing to the 2014 Revolution of Dignity, Ukraine has appeared in the European and global information space. A global community started talking about Ukrainians as an independent nation that shares European values, but is still unfamiliar to foreign neighbours. And here is where educational cultural work comes in as an essential driver of change. Martin says:

“It is crucial to show the Germans a little more about Ukraine, the real Ukraine: how people live, what their mentality is, and what traditions they have.”

In addition to masterclasses, Nataliia and Martin organise literary evenings. They organised the first literary evening in Hamburg as a meeting with the Ukrainian writer Oksana Zabuzhko.

“She supported us a lot and saw that we had a desire, a dream to do something. Because I was a little scared, I thought about her as a woman of a high level, an intellectual. We heard a lot of good things from her.”

Curiously, for Martin and Nataliia one of their first common topics for discussion became Oksana Zabuzhko’s novel “Museum of Abandoned Secrets”, which Natalia advised Martin to read:

“I said then, ‘Martin, there is this book, which came out in German!’ A few days later, Martin said, ‘I already bought it’. A few more days passed and he said: ‘I’ve already read it’. So, I thought, if he has read and understood this text, that text must just be for him.”

Beyond the fact that literature helps to build a cultural dialogue between countries, it is essential to Ukrainian emigrants, because it appeals to them to return to their roots and realise their nationality. The generation of Ukrainians, who emigrated to Germany during the Soviet era and even more after its collapse, find it difficult to identify with their nationality and culture due to long-time assimilation. The literature returns them to the forgotten past and reminds them of their roots. Nataliia is convinced:

“People who are living now in Germany mostly left Ukraine when it was a part of the Soviet Union. So here all the things were inaccessible and unknown to them, so when we invite Oleksandr Irvanets here, for example, it is a discovery for them. We have a friend from Rivne, who didn’t know that Irvanets wrote such an incredible novel ‘Rivne / Rovno (Wall)’. In some way, we catch up with what our fellow citizens did not receive. Such events together with writers create and unite the community, because they always mean conversations and reflections.”

Nataliia is happy about positive changes in the cultural life of Ukraine. She is especially pleased with the appearance of the Ukrainian Book Institute and the Ukrainian Cultural Foundation, as it became easier to make contacts through official representatives on both sides. In this regard, the conditions of quarantine were favourable, because without any hassle and extra expenses you can arrange literary readings, discussions, or even concerts online. However, Nataliia still plans to return to the live format. Thanks to the Paul Celan Literary Centre and the Meridian Czernowitz project, literary readings with the participation of Serhiy Zhadan, Igor Pomerantsev and other writers are planned for December 2020.

Nataliia and Martin notice that the Germans are gradually beginning to identify what is Ukrainian and separate it from Russian. Recognition of Ukraine is now growing not due to political perturbations, but due to awareness of ancient traditions, crafts and talented Ukrainians. And this is what forms a positive image of the country abroad:

“It’s great that there is an opportunity to join in with something, in some way to coordinate something, to help, to advise, to become a liaison to people. That’s how it works. So, you see the result of those efforts in the discovery of Ukraine by the world.”

supported by

The material was prepared in cooperation with the NGO “Atelier of Culture and Sports” together with the Foundation “Memory, Responsibility and Future” (EVZ), “MEET UP! German-Ukrainian Youth Meetings” and “Culture for Change” programmes with the support of the Ukrainian Cultural Foundation.