Media is one of the many tools that Russia uses in hybrid war. The aggressor country has tamed its mass media making it a mouthpiece for Russian propaganda. Unfortunately, Russian propaganda has reached international platforms as well, including respected media with a long history of work. Even without the direct influence of Russia, journalistic ethics and objectivity of some international media outlets begin to falter. We would like to share some specific cases of how global media works in favour of Russia.

Russia has been discrediting Ukraine in the media space for decades. One narrative has already become a classic, Russia says that Ukraine is an unsustainable country, a stateless state. Packaged in various words, Russia has been spreading this myth among academics, cultural figures, mass media, politicians, and social networks. “The Ukrainian language is a dialect of Russian”, “the Ukrainian economy is collapsing”, “there are only alcoholics and corrupt officials in the Ukrainian army ” – these are just some messages based on the same narrative. The messages were created to discredit Ukraine in the eyes of the international community, and thereby to interfere in any attempts by Ukraine to build close multi-lateral cooperation with the world.

The discrediting became especially noticeable in 2014, after the Revolution of Dignity, the Russian invasion of eastern Ukraine, and the temporary occupation of the Crimean peninsula. However, the worst thing is that these Kremlin narratives were picked up, replicated, and scaled up by the international media. Many journalists did not even bother to do at least basic fact-checking. This is not the end of the problem, as there are many more methods of how Russia is being supported on the information front.

Revolution of Dignity

Ukrainian peaceful protests against a Russian course of “development” for Ukraine. After a violent crackdown, a long campaign against the usurpation of power began. 107 victims of the Revolution, called the Heavenly Hundred, were officially identified.Russian fakes in the international media

The most striking example of how Russian messages of dubious quality are spread in the mainstream media is undoubtedly the British news agency Reuters and the Reuters Connect platform, which provides subscribers with news from more than seventy news agencies around the world.

In 2020, Reuters Connect signed a contract with the largest state-owned Russian news agency TASS, which regularly distributes Russian government propaganda and disinformation. In 2015, The Washington Post published an article citing examples of the TASS agency’s connections to Russian spies in New York. The federal prosecutor’s office charged three Russians with espionage, who, in addition to ties to the Russian foreign intelligence service, were related to an “unidentified Russian news organisation.” The material states that, according to US officials, the organisation is TASS, which has been known to them since its cooperation with the NKVD during the Cold War. By the way, the European Alliance of Information Agencies (EAIA) suspended TASS’s membership in its media association a few days after the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine, stating that the Russian news agency was reporting biased news.

NKVD

The state administration body in the USSR, whose main tasks included intelligence, counter-intelligence, the fight against nationalism, dissent and anti-Soviet activities. In the Russian Federation, the FSB (Federal Security Service) became the legal successor of the NKVD.

The partnership between Reuters Connect and TASS lasted until the end of March 2022. Only after a story by the American media outlet Politico, which included anonymous quotes from Reuters employees and criticism of the platform for cooperation with the Kremlin intelligence agency, did Reuters Connect put an end to this media friendship.

However, the termination of cooperation with TASS didn’t stop Russian fakes from appearing in Reuters publications. The British news agency continues to rely on Kremlin publications in some of its news.

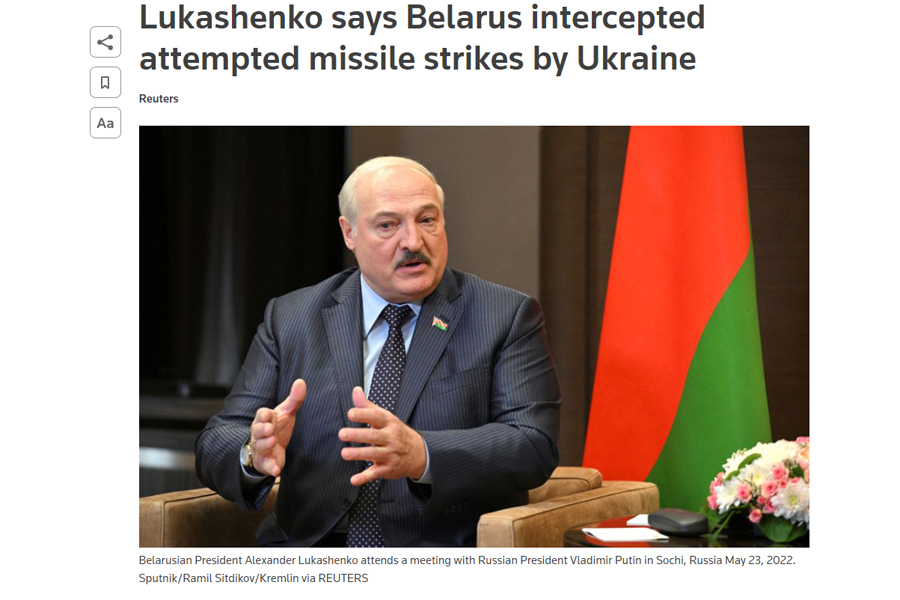

One of the most alarming materials in this regard was published on Reuters on 30 May 2022 under the title “Pro-Moscow Kherson region starts grain exports to Russia — TASS”, where they rely on information from the Kremlin news agency, not even hiding it. The title was changed on the same day to “Russian-controlled Kherson region in Ukraine starts grain exports to Russia — TASS.” But it didn’t get any better, because the source of the news remained the same, and most importantly, Reuters readers will not learn from this news that grain was forcibly removed by the Russian army from the temporarily occupied territories of Ukraine. On 3 July 2022, Reuters published a material titled “Lukashenko says Belarus intercepted attempted missile strikes by Ukraine.” This is obvious disinformation, because Ukraine has neither intentions nor reasons to attack Belarus. This is a clickbait media message, the value of which is questionable even for this remark: “Lukashenko, who did not provide evidence for the claim.”

The Fix investigated the activities of Reuters in covering the events of the Russian-Ukrainian War. The author of the article, Sofia Padalka, tells the story of cooperation between news agencies, citing examples that prove Reuters is playing into the hands of the Russian Federation, in particular, during the full-scale war. The Fix draws attention to the vocabulary of the Reuters material which distorts the reality of the war. The Fix journalists quote Polish academic Jan Smoleński in regard to the news about temporarily occupied Kherson:

— If the region is pro-Moscow, then what’s wrong with it being Russia-controlled? Thereby [this wording is] legitimising fait accompli.

In addition to the story about Kherson, The Fix journalists analyse ten materials about Ukraine on the Reuters website with the keywords “stolen grain”. Only four of them have exactly this wording in the title, the rest say “exported grain”, which is not true. Also, when it comes to Ukrainian territories, the wording “supported by Russia” and “supported by Moscow ” is often used instead of “occupied by Russia”. This creates the illusion of a civil war in Ukraine, not a full-scale invasion launched by Russia.

On 10 October 2022, the day of the massive Russian bombing of civilian infrastructure in Ukraine, Reuters published a story titled “Red Cross pauses Ukraine operations for security reasons”, which they later changed to “Escalation of violence in Ukraine disrupts aid work”. In the article, they spread falsehoods, because the International Red Cross did not leave Ukraine. They also “quote Moscow” without adding either the source of the quote or the context, which frankly does not meet journalistic standards and becomes a kind of sabotage during a full-scale war.

— Moscow says the strikes were against energy, command and communication targets in retaliation for what it describes as terrorist attacks (alluding to the destruction of the Crimean bridge. — ed.).

According to LOOQME, this news with the original headline was quoted by 366 publications from all over the world in just the first day, so any further denial or change of the headline will no longer make sense. Such examples are quite a problem, because the Reuters website alone has an audience of more than 65 million readers per month.

In addition to Reuters, there are other influential media that show the situation in Ukraine through a distorted mirror. The stories by the international media about the Russian-Ukrainian War often lack context, journalists don’t know the history and specifics of Ukraine’s relations with the Russian Federation. They also don’t perceive Russia as a terrorist country with imperial ambitions, and they refuse to see the Russian population as being involved in the war. The results of this incompetence are biased and even manipulative materials that play into the hands of the Russian Federation.

For example, international media still actively use the term “separatists”, referring to the leaders of the self-proclaimed LPR*, DPR* and the temporarily occupied Crimean Peninsula. The audience with a limited understanding of Russian-Ukrainian relations and the war in particular perceives it as a civil war, because journalists don’t mention the most important part: Russia supports and sponsors these criminal groups while unlawfully sending its troops and ammunition to the Ukrainian sovereign territory.

LPR

LPR is a self-proclaimed Luhansk People's Republic, considered internationally to be part of Ukraine.You can find these kinds of mistakes in the materials of many news agencies and media outlets. For example, the publication of AFP News Agency from July 2 about “Ukrainian separatists” was picked up verbatim by international media with Middle Eastern roots — AlArabia and Al Jazeera, while French media Le Monde and German Deutsche Welle turned it into “pro-Russian rebels”.

DPR

DPR is a self-proclaimed Donetsk People's Republic, considered internationally to be part of Ukraine.

Even though many foreign journalists come to make their stories about the full-scale war directly in Ukraine, learning the truth and seeing the war crimes of the Russian Federation with their own eyes, this is still not enough to clear the media space of Kremlin narratives. However, the reaction of Ukrainians to manipulative statements and unverified information is much more active, constructive, and sometimes instantaneous since the moment of the full-scale invasion, which helps to affect the global information agenda. For example, the representative of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Ukraine Oleg Nikolenko quickly reacted to the AFP News Agency headline “Ukraine separatists say they have encircled Lysychansk” on his Twitter account. And the materials of Reuters are now under the close attention of Ukrainian activists and media figures.

Discrediting Ukraine and its military

An absurd story happened in the USA in regards to the Azov Regiment — a unit of the National Guard of Ukraine. Vyacheslav Likhachov, a historian and expert on far-right radicalism, talks about it in his op-ed for The Ukrainian View blog on the Medium platform:

— A few years ago in the United States, they discussed an initiative to recognize Azov as a foreign terrorist organization… Previously, only Islamists, some national separatist movements and left-wing radicals were on this list. However, the initiators guided by the false media image didn’t even understand that this was a detachment of a state body, not an informal paramilitary group.

FTO list

FTO list (Foreign Terrorist Organizations) is a list compiled by the US Bureau of Counterterrorism.

In the end, Azov didn’t make it to this list, but the media’s attention remained focused on the Ukrainian military, and the narrative about the Azov battalion as a “militia” or a “paramilitary group” stays to this day. In fact, Azov has been an official organisation from the very beginning — first as a battalion of the special police patrol service of the Ministry of Internal Affairs, and later as part of the National Guard.

Russian authorities and propagandists have been demonizing Azov for many years, presenting it as a neo-Nazi organisation. There are a lot of fakes in the media and social networks about Azov’s symbolism and role in Ukraine. Even if you enter the word “Azov” into the search engine, most likely, Google will offer to add “Nazis”. Such a situation not only harms the reputation of the National Guard special forces, but also has real negative consequences for its soldiers. Due to prejudices and stereotypes about Azov, the governments of Western countries could refuse military aid and training to this particular unit.

Russian propagandists actively spread the word about neo-Nazism in Ukraine back in 2013 and strengthened it when they found a perfect subject for this — the Azov Regiment. The history of the founder of the regiment Andrii Biletskyi* is connected to right-wing radical groups and the nationalist party. This is what the Kremlin’s media henchmen built their absurd myth on. The rest of the objective information became irrelevant for the Russians, they “ate” what their media provided them without even trying to independently verify the information in open sources. The reason for the establishment of Azov (a volunteer battalion created in the city of Berdyansk to fight against the Russian occupiers in 2014), facts about the founders and its members (it includes people of different nationalities — Russians, Jews, Crimean Tatars, etc.), and their activity in general (official military service) — all this has been ignored by the Russians and many spokespeople globally.

Andrii Biletskyi

Andrii Biletskyi is a Ukrainian veteran and political figure. He was a commander of Azov regiment in 2014 and a member of Parliament from October 2014 to 2019. On 13 June 2014, the Azov battalion, under the leadership of Andriy Biletsky, played a key role in the successful liberation of Mariupol from Russian terrorists during the anti-terrorist operation in the east of Ukraine.

Stories about Azov as an unofficial paramilitary organisation have been distributed by many international media outlets. Here are just a few vivid examples where the concept of “neo-Nazis” and “fascists” are used as a permanent characteristic of the Ukrainian regiment:

– An article by The Guardian (2018) where they call Azov “a notorious Ukrainian fascist militia.”

– An article by The Week (2018) where Azov appears as a “militia”, and Andriy Biletskyi is called a commander, although he has not been one since 2014.

– A material in Time (2021), which doesn’t distinguish between the concepts of the official Azov Regiment and the Azov movement (the latter is not related to the National Guard of Ukraine). The material states that “Azov” is a whole system consisting of a political party, “militia”, children’s camps and recruiting foreign right-wing radicals.

The myth created by Russian propagandists about the National Corps (Ukrainian nationalist party. — ed.) being the political wing of “Azov” remains in foreign media to this day. For example, on 21 March 2022, the British newspaper The Times mentioned the “neo-Nazi roots of the regiment” and also used an image of a rally of supporters of the political party “National Corps” with the caption “volunteers of the right-wing paramilitary formation ‘Azov’ rally in 2018”. In this caption, everything is wrong: both the definition and the fact that the National Corps is identical to Azov.

As historian Vyacheslav Likhachov explains, the founder of Azov Andriy Biletskyi uses the reputational capital of the regiment in his political life:

— Biletsky is trying to exploit the Azov “trademark” in political life. After returning to public life in October 2014 (after military service – ed.), he founded a political project called the Azov Civil Corps. Andriy Biletsky welcomed veterans of the regiment into the National Corps Party and other organizations around the party that he called the “Azov movement.”

Azov Civil Corps

A right-wing socio-political movement formed in the spring of 2015 by Andriy Biletskyi.One of the journalists who has been actively spreading propaganda about neo-Nazism and Azov was Christopher Miller, a journalist for Politico and BuzzFeed. Since the start of Russian full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Miller deceitfully changed his stance and now acts as a defender of Ukrainians. But screenshots, so to say, don’t burn. In his Twitter thread, accompanied by his journalistic materials on this topic, Miller writes:

— Azov is well known for having far-right extremists and neo-Nazis in its ranks. The regiment and broader Azov movement has attracted the attention of Western extremists who’ve gone to Ukraine to train with the group. Journalists, including me, have done extensive reporting on Azov.

Christopher Miller has been actively writing for BuzzFeed about the Ukrainian far-right movement, dramatically exaggerating its role. In some of his articles, you can find the following judgement: “The country (Ukraine) has emerged as an important hub in the transnational white supremacy extremism network”. He didn’t separate the “Azov” regiment and the “National Corps”. In a story for Radio Free Europe, he wrote about the connection between American criminals and Azov, without specifying that the regiment is an official structure in the ranks of the National Guard, not a paramilitary organisation. Thus, together with other journalists, he supported one of the main messages of Russian propaganda — the one about the so-called Nazis in Ukraine.

Some foreign media have gone even further: they question the existence of Ukrainians as a nation and call on the US not to interfere in the “territorial dispute” between Ukraine and Russia. We are talking about Tucker Carlson from Fox News, who is always between love and hate in the US. He started out as a columnist and journalist, has a long career on television, and since 2009 has been one of the main voices on Fox News. His approach has been called the “grievances politics,” which is based more on indignation and antagonism to certain groups of people than on objective analysis of the facts. When it comes to Tucker Carlson’s way of reporting, everything is very confusing, conspiratorial and close to fanaticism. He uses poor language and very simple expressions in his reporting which leaves an aftertaste that everything is very clear, but at the same time nothing is. George Orwell defined this approach as one of the key elements of propaganda in his essay “Politics and the English Language”. Such broad strokes allow Carlson to manoeuvre, expose people to populist ideas.

All in all, this does not absolve the media from responsibility — the contexts they create and reproduce in the mass media or on their social networks feed Russian propaganda, and therefore indirectly help the Russians kill Ukrainians.

News through the Russian lens

Since the beginning of the Revolution of Dignity (also called Maidan Revolution or Maidan – ed.) and the temporary occupation of Crimea, some international media broadcasted their content from Russian offices or employed journalists associated with the Russian Federation. The leaders of these mass media companies didn’t consider it a problem.

Among the global media that directly or indirectly play along with the aggressor country, there are those whose reputation is seemingly impeccable. One of them is the oldest and most popular American publications, The New York Times (NYT), with about 500 million visits on the website and about 120 million unique readers per month. This media has received 132 Pulitzer Prizes — the most of all outlets (Ukrainian journalists, by the way, received one prize for all). Many controversial stories have been associated with NYT since the beginning of the 20th century.

The NYT received a lot of criticism from Jewish organisations because of its poor coverage of the Holocaust during World War II. “Between 1939 and 1945, The New York Times published more than 23,000 front-page stories. Of those, 11,500 were about World War II. Twenty-six were about the Holocaust.” stated the American media outlet The Daily Beast.

Before World War II, the NYT also claimed that “Hitler’s anti-Semitism was not so violent or genuine as it sounded”. A professor of journalism Laurel Leff even wrote a book about this era of the media’s history called “Buried by the Times: The Holocaust and America’s Most Important Newspaper”. She criticised the reporting of this prominent American media during the war and interwar periods.

Anglo-American journalist Walter Duranty, who denied the Holodomor, headed the NYT’s Moscow bureau for 14 years (1922–1936). Winner of the 1932 Pulitzer Prize for his reporting from the USSR, he claimed that there was a food crisis in Ukraine while in reality, people were dying en masse. He also criticised the Welsh journalist Gareth Jones, who was the first to reveal the truth about the Holodomor and who was eliminated by the NKVD. After appeals by Ukrainian-American organisations to the Pulitzer Prize committee to posthumously revoke Duranty’s award, the commission officially refused to do so in 2003. They call the Holodomor “the famine”:

NKVD

The People's Commissariat of Internal Affairs was one of the government ministries during the USSR. It was created in 1917, and in 1946 it was renamed the Ministry of Internal Affairs of the USSR.— The famine of 1932-1933 was horrific and has not received the international attention it deserves. By its decision, the board in no way wishes to diminish the gravity of that loss. The Board extends its sympathy to Ukrainians and others in the United States and throughout the world who still mourn the suffering and deaths brought on by Josef Stalin.

Holodomor

Holodomor is а genocide of the Ukrainian nation committed in 1932–1933 by the leadership of the Soviet Union.

Since the start of the full-scale invasion in 2022, the NYT’s position and content have outraged many Ukrainians. For example, Russian-born journalist Yana Dlugy was appointed head of the daily newsletter “Russia-Ukraine War Briefing” in May 2022, when the full-scale war had lasted almost three months. Yana Dlugy is a native of Moscow. She worked in various media companies there. In particular, she was the head of the Agence France-Presse office in Moscow. Then she worked in the office of the same media company in Kyiv. Of course, why work with Ukrainian journalists, if there is a Russian woman who “spent summer vacations in Odesa as a child”? This is how Yana Dlugy introduced herself after being appointed to this role at the NYT. Dlugy led the newsletter until October 2022 and was replaced by Carole Landry who also used to work in Moscow.

In May 2022, the Ukrainian English-language media The Kyiv Independent published an official appeal to the editorial team of the NYT, reacting to their article “The war in Ukraine is getting complicated, but America isn’t ready.” American journalists questioned Ukraine’s victory and depicted the situation as if the correct “painful compromise” for Ukraine would be to give part of its territories to Russia. “Now the New York Times is calling for the West to do what Putin expected and give up. Make no mistake: If you appease a dictator, whose troops regularly indulge in war crimes, it will lead to a catastrophic geopolitical shift,” says the appeal of The Kyiv Independent.

Previously, the NYT had an office in Moscow, and decided to open one in Ukraine only at the end of July 2022 under the leadership of Andrew Kramer. This caused a wave of indignation among Ukrainians, since Kramer had previously lived and worked in Russia for more than ten years and is known for his contradictions regarding the coverage of Russia’s temporary occupation of eastern Ukraine and Crimea. In 2017, he called the war in eastern Ukraine “civil” (the headline was corrected from “Ukraine Civil War Heats Up as U.S. Seeks Thaw With Russia” to “Fighting in Ukraine May Complicate U.S. Thaw With Russia”). A year later, he called Donetsk and South Ossetia (region in Georgia) “separatist zones”, not territories occupied by Russia, and also tried to get accredited as a journalist in the so-called Donetsk People’s Republic in order to collect materials for his publications there.

Two weeks before the full-scale invasion, Andrew Kramer wrote an article “Armed nationalists in Ukraine pose a threat not just to Russia.” He talked about the Democratic Ax party, in particular, their representative Yuri Gudymenko, who was later wounded in a battle with the Russian invaders. In his article, Andrew Kramer tells Gudymenko’s story. He is ready to arm himself and oppose the government if it decides to negotiate with Russia. The NYT journalist speculates on the topic of nationalists in Ukraine and how they seem to complicate any diplomatic solutions. However, according to the NYT’s official statement: “There is no one better suited to lead The Times” in Kyiv than Andrew Kramer.

Another respected media outlet, The Washington Post, also opened an office in Kyiv in the spring of 2022. They appointed Isabel Khurshudyan as head of the department, who was previously a correspondent in the Moscow branch of the media company. Obviously, this editorial office didn’t put too much effort to find a Ukrainian or international journalist who didn’t work or live in Moscow after 2014.

Someone can argue that it’s great when journalists change the Moscow office for Kyiv, literally leaving the territory where freedom of speech leaves much to be desired and everything is permeated with Kremlin propaganda. Unfortunately, redeployment doesn’t guarantee a change in personal and professional values, so Russians continue to bend their line in global media, one-sidedly covering Russian-Ukrainian relations and the course of the full-scale war in particular.

Another manifestation of Russian perspective in global media is solely engaging experts who are directly or indirectly related to or support the Russian Federation. Instead, speakers from Ukraine remained ignored, unnoticed. The situation somewhat changed after the full-scale invasion, when the media’s attention was focused on Ukraine, and the Russian-Ukrainian war became the key agenda. Since February 2022, Ukrainian voices have been heard in many world media, largely because of the efforts of the Ukrainian volunteers who work on the information front and promote Ukrainian experts and witnesses. However, before the full-scale invasion, it was widely acceptable to talk to a random researcher of Russian history about the situation in Ukraine. It was also common practice to refer to the Russians altogether ignoring the speakers from Ukraine. There can’t be any constructive discussion in this case, most often everything ends with the defence of “ordinary Russians” and blaming the USA for all the troubles.

Comments or columns by pro-Russian speakers about the war are a common practice in Western media. Among such “experts” are American linguist of Belarusian origin Noam Chomsky, American political scientist John Mearsheimer, American historian Steven F. Cohen and others. The latter didn’t live to see a full-scale invasion, but for several years he actively promoted the opinion that there is no authoritarian regime in Russia and that the war in eastern Ukraine started because of the United States.

Anglo-American journalist Christopher Hitchens wrote the book “The Trial of Henry Kissinger” about another well-known “expert” on the Ukrainian issue — Henry Kissinger, a former politician and US National Security Advisor under Presidents Ford and Nixon. Hitchens accused him of war crimes during the Vietnam War and supporting Indonesia’s invasion of East Timor.

How to resist Russian propaganda in the international media

Everyone makes mistakes, and journalists can be influenced by personal prejudices and stereotypes prevalent in their society. However, during the war, the discussion about journalistic ethics and competence goes beyond university walls or expert discussions, because the media content affects the national security of Ukraine and other democratic countries in one way or another.

One can explicitly trace the logic and specifics of how propaganda works in Russia, оbut it’s much more complicated to detect Kremlin narratives and prevent them in other countries. Sometimes, Russian disinformation and fakes get their way to the media stories due to journalistic haste, insufficient editing or the poor judgement of a certain reporter or journalist, whose opinion may not be shared by the editors. Therefore, it will be imprudent to brand the media as propaganda based on one or two questionable materials, but it’s crucial to point out those problems to the editors: indicate it in the comments, write emails to the editors, etc.

Nina Kulchevych, coordinator of the disinformation stream in the Ukrainian PR Army, organisation, says:

— The New York Times, FOX, and other major media have both truthful material and distorted facts with manipulative wording. It’s often necessary to evaluate not only a media outlet as an institution, but the entire holding company or, on the contrary, an individual journalist, its editor, the level of freedom of speech in a specific country and how the concepts of this freedom of speech are manipulated.

For those who want to support Ukraine in the information front, Ukrainian communication experts who had been defending Ukraine in the world media field even before the war, recommend:

1. Check the editorial position (editorial policy) and materials about Ukraine. If you notice that there is a lack of understanding of the Ukrainian context or that the agenda chosen by a journalist distorts reality, you can either refuse to engage or provide reliable information. Recommend qualified experts who can clearly express themselves on the issue and provide verified information on the topic. Many journalists are happy to get more context on the Russian-Ukrainian war and generally expand their knowledge on the topic. It’s best to politely explain why it’s dangerous to broadcast messages from the Russian Federation without any context and explanations.

2. If journalists and (or) the editorial staff of the media don’t respond to your remarks and refuse competent help, you should refer to organisations that combat fakes and disinformation, for example, Detector Media, StopFake, GIS (Global Information Space).

3. In order to create counter-narratives and criticise manipulative materials, you should not use exclusively the argument of authority (for example, “I am Ukrainian, I know better”). Rely on the analysed facts and involve experts who come from the country you are creating the material about. Thus, the material will be more objective, and the discussion will be equal. The audience will trust such material more.

4. Don’t be afraid to stand up for your position, even if the world’s most powerful media is wrong. Large international media often have decades of developing standards behind them, but often these standards are not adapted to the current information war, which means that such media are not authoritative in all matters.

In modern technological wars, the victory is won not only on the real front, but also on the informational and cultural ones. It can be an exhausting marathon, so you need to stay alert. Be emotionally and professionally flexible. Remember that countering Russian narratives in the world media is important, and everyone can join this fight. The democratic world must recognize that we’re all participants in the information war, and that the laws and rules of it have not yet been written. The international media are not just bystanders, but they are also involved in this full-scale war. Every word they spread affects the course of the war and therefore the lives of hundreds of thousands of people in different countries.