With this publication, we are opening the series of stories “Ukrainians abroad”. This series is not about successful immigration rather about people that had moved abroad due to different reasons and started helping Ukraine in various ways: creating state-to-state projects, sharing experience obtained abroad, uniting in Ukrainians communities and spreading Ukrainian culture all over the world.

Jaroslawa Zelinsky Johnson left Ukraine in the closing days of World War II when she was just a few months old. Her family followed the well-worn path of other Ukrainian emigrants through Czechoslovakia to a displaced persons camp in Germany and five years later to the USA. She was educated in the US and attended law school in the 1970s.

While getting a legal education, Jaroslawa kept thinking about Ukraine and during the Soviet period, and she visited her native land twice as part of tourist delegations. When Ukraine became independent in 1991, Jaroslawa was representing Polish-American clients in Poland and eagerly watched for an opportunity to move her law practice to Ukraine, which began in 1992. Since 2015, Jaroslawa has headed an American fund that invests in the economic development of Ukraine and Moldova.

Holding American citizenship and having lived in the USA most of her life, Jaroslawa returned to Ukraine 26 years ago in order to strengthen its economy and bring up a new generation of leaders, and she is still here.

Legal Career

Jaroslawa graduated from the University of Wisconsin University Law School in 1977 with a Doctorate in Law, and moved with her husband to Chicago where she worked as an assistant to a federal appellate court judge and her husband was teaching at the University of Illinois:

— When I received the judge’s offer, my husband told me that if I accepted this offer, he would follow me to Chicago. We loved living in Chicago and decided to stay. There was no Ukrainian community in Wisconsin like in Chicago, where there are Ukrainian churches, a bakery, Ukrainian restaurants, a Ukrainian bank and a Ukrainian school for our daughter.

The heart of the large Ukrainian community in Chicago is located on the northside in Ukrainian Village. Ukrainians began settling in this district in the 19th century. Today, it is one of the biggest centers of Ukrainian culture in the America. Ukrainian National Museum of Chicago, Ukrainian Museum of Modern Art, numerous Ukrainian shops, restaurants and banks are located in Ukrainian Village:

— We have an Orthodox Cathedral and two Greek Catholic churches. One Greek Catholic church was founded at the beginning of the 20th century and the other in the 1960s. They differ only by celebrating holidays at different times. One church celebrates according to the Julian calendar, the other follows the Gregorian calendar. On the whole, Chicago has a different culture than other American cities. It is less aggressive than New York. I like its dynamic city center. Ukrainian Village is a lovely district as well. But the spirit of Chicago can be seen in its center, where people work, where everything is moving, and life is in full swing.

After working with the judge for two years, Jaroslawa began practicing corporate law with a Chicago law firm. Shortly after the Berlin Wall fell and central Europe abandoned communism, she advised multi-national clients on investments in Poland and a few years later, after the USSR dissolved, she moved to Ukraine:

— My Chicago law firm represented many Polish clients because the city had a well-developed Polish community. That is why I visited Poland two to three times a year for several years representing Polish-American businesses interested in rebuilding post-communist, independent Poland. And Poland in 1990–91 was in that same bad shape as Ukraine. I kept thinking that it should happen in Ukraine, too (the independence — ed.) And then within a year, it did happen. Ukraine became independent. Several clients wanted to do business in Ukraine. My first client was an American pharmaceutical company. Afterward, I facilitated the purchase of a factory in Kharkiv for Philip Morris and confectionery plant in Trostianets for Kraft Foods (nowadays it belongs to brand Mondelez — ed.). One by one investors started coming to Ukraine.

The move to Ukraine occurred in 1992 when Jaroslawa was retained to represent American companies interested in expanding their business to the Ukrainian market. Subsequently she established a Kyiv office for her American law firm, and Jaroslawa and her team of Ukrainian lawyers assisted many international corporations to launch businesses in Ukraine and invest in local enterprises. Among her clients were companies and organizations that played an important role in opening Ukraine to foreign investors and now hold an important place in Ukraine’s economy such as Monsanto, Philip Morris, Kraft Foods, McDonalds, AT&T, Crédit Agricole, WizzAir Group, EBRD and IFC.

In spring 1993, Jaroslawa’s Chicago law firm asked her to open a branch office of the firm in Ukraine. Opening that office required Jaroslawa to divide her time between Kyiv and Chicago, which meant that she would be absent from her Chicago home and husband and young daughter for weeks at a time. Jaroslawa sought the advice of her husband while she considered her law firm’s offer:

— I asked my husband if I should take the offer and he said: “If you don’t do it, you will later regret that you didn’t take this opportunity”. He was willing to support me. Since my daughter was a little girl back then, my husband was taking care of our daughter Sophia during the school year while I was traveling back and forth. We developed a family routine whereby during the academic year I would rotate working several weeks in Ukraine with weeks in Chicago and at the end of each academic year, my professor husband and daughter came to Kyiv and each summer we lived together for three months in Ukraine. Then in fall they would return to Chicago, my husband to the University and our daughter to school, and I returned to my bi-monthly commuting to and from Ukraine. This lifestyle is not for everyone. Sometimes I am asked how it’s possible to coordinate everything like that. I managed to do it because I had my husband’s support. He liked being in Ukraine, and he saw how the country was changing. It was a positive phenomenon for all of us. Maybe it’s not suitable for everybody, but it suited us.

For the next 20 years, Jaroslawa spent much time on airplanes, flying between Chicago and Kyiv. Jaroslawa recalls that it wasn’t easy to get used to life in Ukraine back then:

— No street lights, no gasoline, no office supplies, no workable telephones for international calls and faxes. The food in Ukraine in those days was quite different than it is now. In those days, Ukrainians seemed to eat the same thing three times a day, and I would bring to Kyiv non-perishable food I enjoyed in Chicago.

— The constant travelling takes a toll on the body and lifestyle, but I like Chicago because it’s easy to fly to Ukraine from Chicago. It’s a bit more complicated from other regions of the USA. I think I wouldn’t have lasted for so long if I hadn’t lived in Chicago.

Providing corporate legal services to Western clients in Ukraine wasn’t easy in those days, either. Jaroslawa recalls that one of the greatest complexities of work in Ukraine was inoperative banking systems in the early 1990s. Even large business deals with the state had to be carried out in cash, often stuffed into suitcases:

— You couldn’t come with a certified check from a reputable international bank and give it to Ukrainian officials and businesses. They didn’t know what to do with it. We conducted negotiations on purchasing the chocolate plant in Trostianets for almost half a year. We came to Trostianets and signed all the paperwork, and our client took out from his pocket a beautiful check for three million dollars from the biggest bank in Switzerland. And Ukrainian company officials and even the State Property Fund did not know what to do with it. They wanted cash. We didn’t carry that amount of cash with us anywhere. So, we flew to Kyiv and called all banks but they didn’t have this amount available. But one French bank just started operating in Ukraine. We called them and asked if they had any cash. They happened to have the necessary amount and we went to close the transaction. The bank was just setting up and had no tables, so we arranged all the transaction documents on the floor, signed everything and the head of the bank took the money out of the safe and gave us cash. That’s how we bought the plant in Trostianets.

Simultaneously, Jaroslawa was assisting the McDonalds chain to register and open the first restaurant in Ukraine on Khreshchatyk street (the main street of the Ukrainian capital). She recalls that the transaction required coordinating numerous elements from renting premises to importation of specific components for McDonalds menu including buns, potatoes and meat. It wasn’t until a year later that McDonalds located local suppliers who met the company’s standards:

— McDonalds corporate headquarters is actually located in the Chicago suburbs. That’s where they have Hamburger University, where they teach people to become franchise operator, make hamburgers and fry potatoes. At that point, people in Ukraine knew about McDonalds. We didn’t have to persuade the Ukrainian government since there was a McDonalds in Moscow. Everyone wanted to have this kind of restaurant because McDonalds arrival in Ukraine meant that we did something successfully.

Western NIS Enterprize Fund

In 1994, US President Bill Clinton appointed Jaroslawa to the Board of Directors of the Western NIS Enterprise Fund. It is a private equity fund sponsored by the US government for the purpose of investing in small and medium businesses in Ukraine and Moldova:

— President Clinton selected business people who were connected with Ukraine. He thought that such people had knowledge and experience that would be useful for Ukraine. That is why we were part of this group. At first, our fund was oriented toward three countries: Ukraine, Belarus, and Moldova. However, Lukashenko (the President of Belarus for the last 25 years) evicted us from the country, he didn’t want an American fund working in Belarus.

In 2014, Jaroslawa’s Kyiv law office was closed by the American firm’s headquarters. After moving from Kyiv back to Chicago and a brief retirement, Jaroslawa was invited to return to Ukraine to become the President and CEO of WNISEF. Since then, Jaroslawa has managed four major programs sponsored by WNISEF promoting exports and investments, strengthening local communities, supporting small businesses committed to solving social issues, and developing a new community of leaders:

— I believe that as soon as Ukraine becomes economically stable it will become politically stable as well. That’s why I have always tried to show both foreign investors and Ukrainians that honest and well managed business can benefit the state and the citizens. One of my staff members visited Trostianets recently. And she told me: “You know they employ 1500 people and all of them are content, there is no unemployment, children are well dressed, parents have money to send their children to universities”. Why isn’t it possible to implement this success in other cities of Ukraine? You know, it is possible. The aim of the Fund is to further support development of small and medium business in Ukraine. Each small business is a mini-economic zone, which helps the city grow, provides people with a good living standard.

Ukrainian Leadership Academy

The Ukrainian Leadership Academy was established by the Fund under Jaroslawa’s leadership in 2015. The Academy is a 10-month program for high-school graduates aged 16 to 18, based on the Israeli mechina model. The purpose of these schools is to educate a new generation of leaders who are ready to serve their country. Jaroslawa is a member of the initiative working group of the Academy, and she also teaches a class in English-language literature to its students on all campuses:

— Erez Eshel is the author and founder of the leadership academies in Israel where there are 60 such schools. As I listened to Erez explain the leadership academy concept, I was captivated and wanted to learn more. We went to Israel to look at nine academies in three days. Erez arranged a pretty tight schedule, we hardly slept on the trip. We traveled all over Israel, explored those academies and met with the young people. They turned out to be adult in their perception, they knew what they wanted, they understood their state and its history. They were passionate about their country. We hadn’t seen passion like that in Ukraine. And I recognized this was a great idea. I introduced the leadership academy project to WNISEF’s board of directors. The board liked this flagship project and approved funding.

These days, Ukrainian Leadership Academy has campuses in Kyiv, Lviv, Mykolaiv, Poltava, Kharkiv, and Chernivtsi, and in upcoming months plans to expand to Mariupol as well. The educational course lasts 10 months and it is free for pupils who qualify. The three elements of development are the core of the program: intellectual, emotional and physical:

— We see the project as very beneficial. We see that its graduates attain a new passion toward their education and their country, their community and their parents. It’s extremely important. It’s not that easy to be a good citizen. You have to work at it. And we want young people to understand what it means to be a good citizen, that they have a duty and responsibility to themselves and their environment. We can see this quality in them, they will be outstanding Ukrainians. I am positive that we will succeed.

mechina model

training for young leaders, established in the begging of 2000ies in Israel

Family History

Jaroslawa was born in the Brody, Lviv region. Her mother was from Liuboml, a small town in Volyn region, and her father grew up in Kremenets:

— They were very strong-minded Ukrainians. My father was a teacher, my mother was a school administrator and translator who knew German language, which later saved her life during war time. As a child I was told that my father was “in the woods” during the War, but I never knew what he was doing there. My parents were afraid to talk about it even in the 1950s in America. Five years ago, I went to Liuboml where a secondary school history teacher created a small museum of recent Liuboml history. There were photos from the 1920s to 1940s. There is one photo with a big group of people, it is captioned “Ukrainian Insurgent Army organizational group.” My father is in that photo. That’s how I learned for the first time that he was in UIA.

The Zelinsky family emigrated to the USA after World War II. Eleven family members managed to leave Ukraine during the chaos of 1944:

— As the war was ending, there was a brief time when it was possible to flee as the German Army was retreating and the Red Army was advancing. There were two or three weeks of chaos. I was just three months old. All my mother’s family were leaving Ukraine and my father’s mother and his sister didn’t want to cross over the border. My father tried persuading my grandmother by saying: “We have a cart. You will get on a cart and we will all leave together”. But she responded: “You know, I don’t want to leave Ukraine, you will come back when you can and take us with you.” But my father wasn’t able to come back. The Soviets closed the border. So, we ended up in Czechoslovakia, and then in Germany. And sometime later in 1944, my father lost all contact with his mother and sister until 1958 when his sister managed to find him.

The Zelinsky family’s European trek ended in the American occupation zone of Germany and five years later, they were transported with other immigrants by a US troop ship to the US. The Allies, the European countries and the US who controlled post-war Europe, feared that millions of displaced persons would continue to destabilize Germany and impede its rebuilding and decided to resettle Ukrainians and other immigrants to different countries:

— They wanted these displaced people to be distributed across the world. Some of them remained in Germany, but the majority were sent to other countries according to quotas. Some went to Argentina, Brazil, Canada, Australia and the US. Some were forced to return to the Soviet Union. And there were people who didn’t want to return to their homeland and committed suicide. When we were embarking on the ship in Bremenhaven, we each were given cards with our names and our US destination in English and ten US dollars.

The cost of Zelinskys’ travel from Germany to New York was covered by the United Nations’ refugee resettlement program, which also found a Pennsylania farmer to sponsor the family’s first months in the US. In exchange for food and housing for several months, Jaroslawa’s parents had to work for the farmer:

— These were his requirements. My father was a teacher and he didn’t have the slightest idea what to do with the fork, but he had to learn. So father started helping him at the farm and my mother was involved in kitchen work. We lived there for half a year to pay back everything we owed. Then we moved to Baltimore where my aunt Hanna lived with my grandmother and grandfather. So we were like a small Ukrainian community in Baltimore.

The first wave of Ukrainian immigrants came to Baltimore before World War I, but by the time the Zelinsky family arrived, these early immigrants had already assimilated into American society. Most early immigrants, their children and grandchildren no longer spoke Ukrainian and only the two Ukrainian churches kept the community together.

Unlike prior waves of Ukrainian immigration, the post-World War II immigrants were not so much economic refugees as political. This generation of Ukrainian immigrants to the America fully expected to return someday to the homeland. In the interim, the immigrant community discouraged assimilation and took steps to preserve their culture, traditions and language by establishing schools of Ukrainian studies in several American cities:

— At first, the Baltimore school met in a park, then our parents found other premises. For me and other immigrant children, each Saturday was not a day for fun but to study Ukrainian history, literature, geography, songs and stage St. Nicholas day and other holiday performances. These immigrants carried love for Ukraine and wanted to pass this treasure to their children. But they also brought some negative political baggage with them like political disagreements rooted in Ukraine’s war-time independence efforts which had historical significance but were meaningless in the US.

Jaroslawa visited Ukraine in 1976 with her grandmother. Back then, you could get to Ukraine only if you obtained a permit from Intourist (a Soviet tourist agency responsible for foreign tourists — author):

— My grandmother was 84 years old and she had been on an airplane. During that trip, she was able to find her younger sister whom she hadn’t seen for 38 years. My great aunt was resettled to Lviv after exile in Kazakhstan. Despite being forbidden to go anywhere without a tour guide, we went to visit her. We were settled in hotel “Dnister” and a man followed us everywhere, but we managed to find my great aunt. When she saw my grandmother, the first thing she said: “You’ve grown old”. It was a great trip for me because I was able to come back to Ukraine for the first time. I am also glad that I was able to take my grandmother with me since she never imagined that she would have an opportunity to return to Ukraine.

The second trip to Ukraine for Jaroslawa took place in 1990 with her husband, daughter, and mother. They again had to travel with the help of Intourist, but it was now easier to travel the country:

— We could see that Poland had become quite independent and that tremendous changes were on the way. That was a great trip: we visited Lviv, Kyiv, and Liuboml. I have now been in Ukraine for 26 years, over a quarter of a century, and even though I am a citizen of America, I am not quite an American anymore but not a Ukrainian either. “Half na piv” (from Ukrainian “piv” — half, meaning half and half) as they say in the diaspora. I can say that I am following my father’s wishes to a certain extent. When I was born, my father told my mother: “You know, when the war is over and we come back to live in Ukraine, I would like to see Jaroslawa go to study in Kyiv University”. Obviously, it never happened but the fact that I would come to Kyiv at some point was foreseen by my father.

Preserving Family Recipes

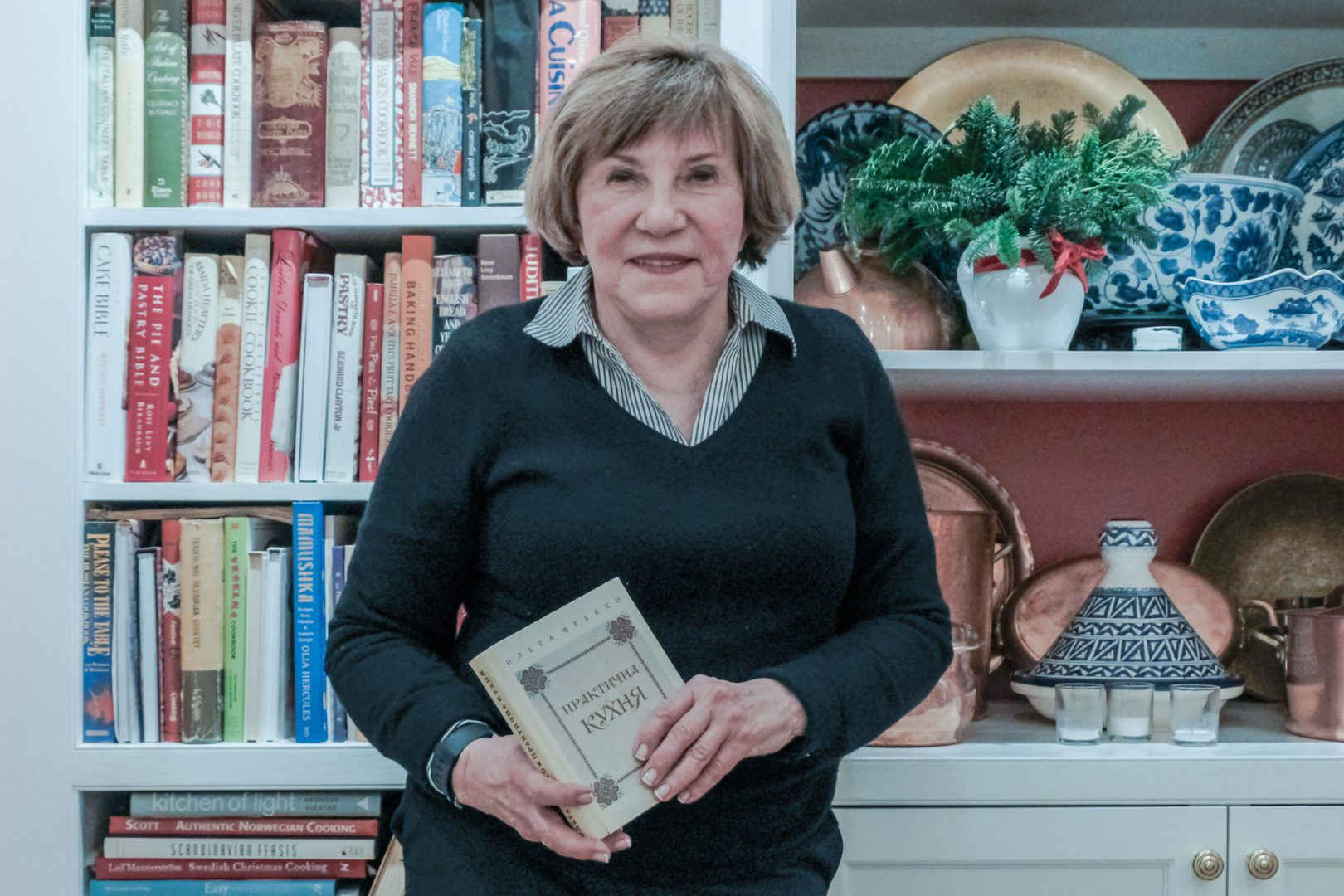

Aside from her professional career, Jaroslawa shares with us her passion for cooking that started during her travels over many years. When visiting a new country, she is always interested in local markets and cookbooks:

— I was consumed by an idea that the first and most important thing in any culture is food. In order to understand another culture, you need to understand what they eat. That’s why in every country I want to see how the market operates and what kind of food they sell there. My collection of cookbooks consists of 500 books. Sometimes they are available in English and sometimes I have to buy them in a native language and translate them myself.

According to Jaroslawa, the cuisine of immigrants differs from that in the homeland. Ingredients are different in different countries, so cooks have to adapt traditional recipes in a new way:

— Even if the products are the same, they can be of different quality. For example, Ukrainian butter is fattier and flour is softer, that’s why pampushky (a small savory or sweet yeast-raised bun) are not as soft in the US as in Ukraine. Some ingredients don’t exist in the US at all. American sour cream is very watery while Ukrainian is of a quality that a spoon will stand in it. All immigrants adapt their cuisine, and you can see how the Chinese, Koreans and Polish do it here in Chicago.

Jaroslawa did not graduate from any famous culinary school but she taught herself about food preparation by taking classes in various countries, from observing other cooks and reading cookbooks. Jaroslawa says that she likes to learn new things and the process of cooking brings her great satisfaction, a sense of accomplishment:

— I became involved in this hobby so that I could get a positive result at the end of the day. Daily legal work will not give you such a result. You can work all day with legal documents and purchasing a factory may take eight to nine months. You prepare legal papers, do your reading, go to negotiations and there is no quick result. After spending my days and weeks and months practicing law, I wanted to do something creative, something that could give me a definite result within a short period of time. For me, it’s cooking. It’s a pleasure that I can cook well, serve beautifully and the result will taste great to my family and guests; it matters to me a lot.

In 2010 Jaroslawa decided to write her own cookbook “Legacy of Four Cooks” about the cooking traditions of the older generation of women in her family. The purpose of the book is to preserve the recipes for the dishes that were cooked in the Zelinsky family after immigration. Her cookbook was originally published in English and this year it was published in Ukrainian:

— Inspiration for the book came with my realization that the Ukrainian food culture taught me by my grandmother Yuliya, my aunt Hanna, my mother and my aunt Mariya would not be passed to the next generation unless I did something about it. I wanted my daughter and her peers to understand how it happened that we moved to America, what our goal was, and what we ate the first years in America. All these recipes make sense only in the context of our immigrant life because I am sure that my mother and aunts cooked differently when they lived in Liuboml.

Jaroslawa says that post-war immigration is abstract and distant for the younger generation who grew up in the US. The recipes preserved in her cookbook are a reminder of the life and struggles of the first generation of immigrants and show how traditions were preserved for their grandchildren:

— My mother managed to see this book when she was 93 years old. She was surprised to remember some of those dishes. She said: “Oh, I haven’t cooked this dish for a while”. And I asked her why? She said, “You were picky and didn’t want to eat it. So, I stopped cooking it.” And it’s true: that’s how some traditions vanish. That’s is why I tell younger children in our family: “You know, you have to try at least one bite of this dish and then you will know whether you like it or not.”