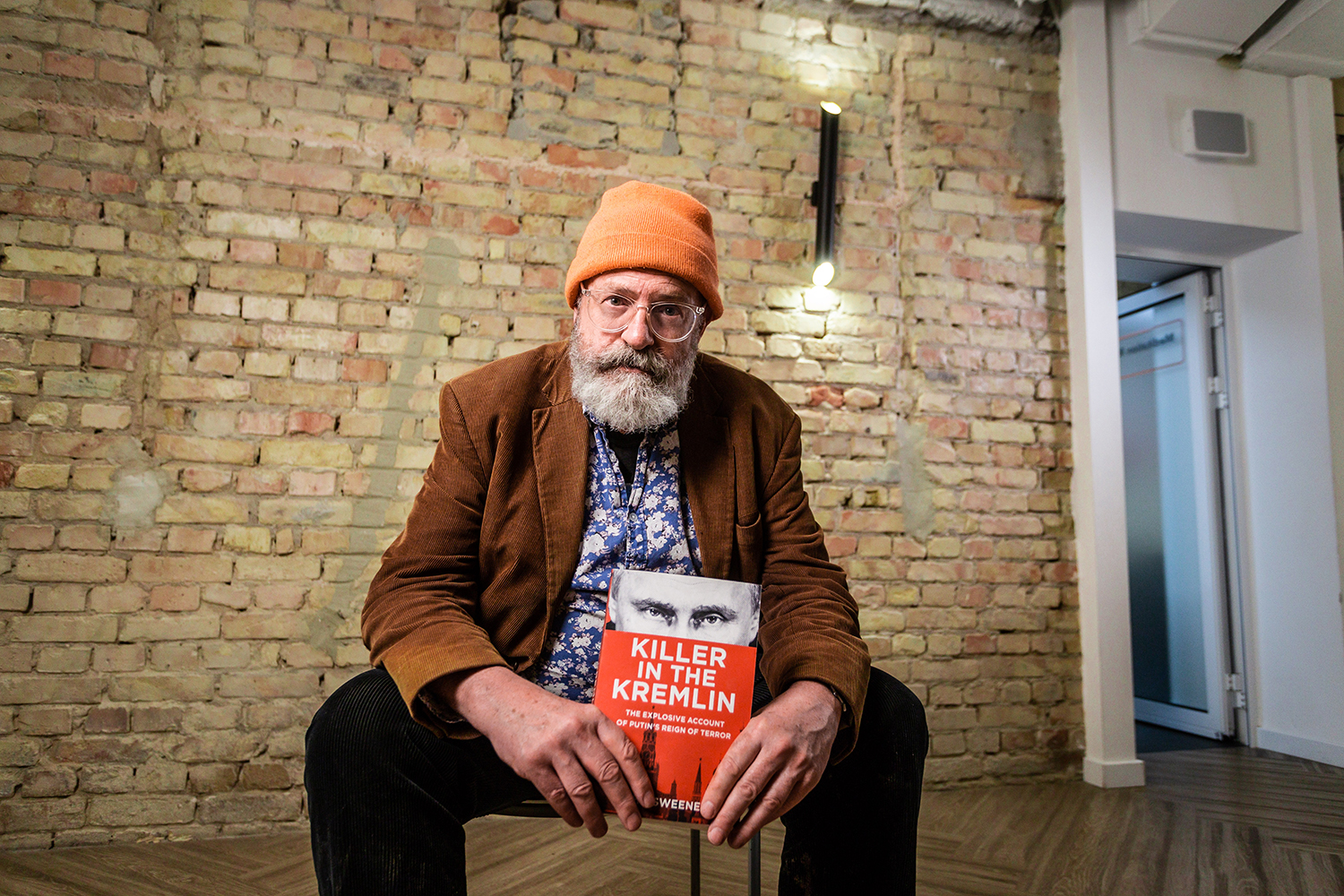

Our next episode of Ukraine Through the Eyes of Others features John Sweeney, a British writer, reporter, and formerly investigative journalist at BBC, currently covering the Russian war against Ukraine. In this interview, he shares his thoughts on Russia’s systematic war crimes, his experience as a journalist covering Putin for years, and living and working in Ukraine during the full-scale invasion.

Ukraine Through the Eyes of Others is a special series aimed at highlighting the perspective of the international journalists, researchers, analysts, and experts from different fields on the Russian war against Ukraine.

John, in your description on Patreon, you say — “what gets me out of the pub is when power and money say to ordinary people, ‘You shut up.’” Could you elaborate on that?

Well, in very simple terms, I was one of the first journalists to call Vladimir Putin a war criminal 23 years ago because, when I went to cover the war in Chechnya, I saw compelling evidence of the Russian army killing refugees. I also witnessed evidence of them using fuel-air bombs against civilians and employing torture on a massive scale. I wrote a story for my newspaper, The Observer, labelling Vladimir Putin a war criminal, but no one listened to me. For far too long, the West backed away from standing up to Vladimir Putin because of our greed, cowardice, and stupidity.

There was a kind of group thinking that deemed Putin too powerful and the story too complex. However, there was another aspect to consider. I went undercover to Chechnya twice in 2000 and reported solely on the final part of the second Chechnya war that Vladimir Putin initiated. I explore this in my book Killer in the Kremlin. The significant bloodshed began the moment Vladimir Putin became Yeltsin’s prime minister, essentially destabilizing Russia. We had this understanding because I published the story in my newspaper, The Observer. I value facts and evidence and don’t rely on psychic abilities. I believe that MI6 and the CIA were well aware of what was happening. One of the reasons I make this claim is that my friend Christopher Steele, the former MI6 officer and head of the Russian Department at MI6’s Russia House, part of British intelligence, informed me so. Christopher and I, along with many others, believe that Putin’s original sin was the Moscow bombings.

The reason the West looked the other way was because of 9/11. There was a 9/11 incident in 2001, and suddenly, the West developed a deep fear of radical Islam and Islamism. This fear encompassed Afghanistan, the place where the New York attack was planned, as well as Muslims residing in our own Western countries. I acknowledge the genuine existence of this fear, but I believe it to be excessively paranoid and exaggerated. The real peril lies not in Islamist terror cells and units but in the nuclear-armed terror emanating from Putin’s regime.

We were consumed by fear, and I don’t dismiss it—I have experienced being targeted by the Taliban nine times in Pakistan. Hence, I am well aware of its impact. Nonetheless, the far greater threat to global peace and Western security arises from Russia, with China standing behind. The fundamental mistake of the West was to fear Islamism and radical Islam while underestimating the menace posed by Vladimir Putin’s fascist Russia. There were three instances where we should have firmly demanded that Vladimir Putin cease his actions because his behavior resembled that of an unruly schoolboy.

The first instance was the poisoning of Alexandr Litvinenko, a former KGB agent and, at that point, a British citizen, with Polonium-210. I conducted a Panorama investigation on this matter, wandering around Moscow and Saint Petersburg, asking if Polonium-210 could be purchased in a shop. The response was a resounding “No”. The fact is that the Russian state produces it, and it is an expensive poison. After Litvinenko’s murder, Britain expelled four Russian diplomats. However, I find this response feeble, as Putin could easily produce four new passports using his diplomatic passport machine, and four Russian spies would resume their activities in the London embassy.

The second moment was the shooting down of MH17. While the invasion of Crimea, Luhansk, and Donetsk was in violation of international law, it was the downing of that plane that claimed the lives of 298 people, including 10 British citizens. Yet again, we allowed Putin to escape accountability for these deaths. It was a Russian missile that caused the loss of those innocent lives.

It took them almost 9 years to investigate it.

Yes, and the reason was that people didn’t want to lose dirty Russian money in London, and the Germans didn’t want to lose cheap Russian gas. Then the third thing is the Skripal poisonings when they tried to kill a certain Skripal, a spy, and his daughter, but they survived, and they did kill a completely innocent British citizen, Dawn Sturgess. This time, we expelled 120 diplomats worldwide. So, while we’re losing real British lives, Putin is simply printing new diplomatic passports as if it were a game to him. He doesn’t care; it’s all a money play. What we should have done is to exclude Russia from the international banking system, but we failed to do so. And the price of our folly is being paid with Ukrainian blood.

Let’s turn to your work in Ukraine. When was your first experience of coming to Ukraine?

I first came to Ukraine in 2011 when I made a radio documentary about the Holodomor. I went to the London School of Economics, founded by Webb and George Bernard Shaw, and one of my favourite places was the Shaw Library—a beautiful library with lovely, comfy chairs where you can read books. But George Bernard Shaw was an idiot who denied the Holodomor. And I became fascinated with the idea of a clever man who wrote beautiful plays but talked such rubbish because the Holodomor was real. And I did a radio documentary about the Holodomor.

I remember talking to a very elderly Ukrainian woman who remembered Stalin as a child, and when she saw African kids starving with distended bellies, she said she felt so sorry for them because she could remember when she was like that. Malcolm Muggeridge wrote that this was a crime so monstrous no one in the future will ever believe it happened. That’s why I made this radio documentary called ‘Useful Idiots’.

So I know Ukraine, and I bloody love it, but before the war happened, life and everything, I didn’t spend enough time there until February 2022. I came on Valentine’s Day. I’ve had some bad Valentine’s days in my life, I tell you. This one was bloody awful, so sad because you all felt it [the full-scale invasion], yeah, you could feel it, you know…

In the pre-digital times, information could be controlled so easily, that’s why Stalin had no problem with covering the Holodomor or other atrocities. But today, despite living in the age of information, we also see the same issue with some “journalists” justifying Putin’s crimes with talks about Western imperialism and NATO expansion. And lots of people believe them. Why do you think it’s happening?

I don’t really understand it, and it makes me mad. By the way, Stalin didn’t have it all his own way. George Orwell told the truth. As I was reading George Orwell’s Animal Farm, what struck me was the relevance of Squealer and fake news. It’s strange because George Orwell could have never heard of Tucker Carlson, but Carlson is like the Squealer of the 21st century, spreading Kremlin propaganda to the millions of Americans who watch him. He’s the most popular American cable TV host in the United States. It’s unbelievable. He spouts nonsense.

Is it possible to even change the minds of the people who listen to such nonsense every day?

It’s hard, but you have to be an optimist. But there are times when it’s exhausting. Like, for example, Russia claiming it doesn’t target civilians. I was in Kyiv during the battle, and I stayed to keep reporting. I witnessed the police arrive in the morning, and I was one of the first reporters on the scene. I saw them remove the dead bodies of an old man, a mother, and a five-year-old daughter, taking them to the morgue. So the idea that Russia doesn’t target civilians is maddening.

In the early stages of the war, an Indian journalist told me that Zelensky and Putin are the same. My English friends, one of whom is a former Sergeant in the Royal Marines and a big man, had to physically restrain me from hitting that idiot. I was so angry because I was witnessing Ukrainians dying before my eyes. How could anyone think this war is fake?

But I can’t understand the motivation of these “reporters”. Some of them may be paid by officials in Moscow to spread this nonsense, but there are others who willingly engage in it, both on the far left and the far right. I find it utterly maddening, and frankly, it sickens me.

Do you have a story from your time in Ukraine that has stayed with you? Something that deeply touched, impacted, or horrified you?

I’ll share two stories: one funny and one dark. The funny one is about why I love Ukraine and how I was arrested on suspicion of being a Russian spy on the second day of the full-scale war. I was wondering around [and filming in] the area of the Arch of Friendship of the Peoples… what an ironic place…. Suddenly, this soldier, Vlad Demchenko, yells at me: “Stop filming!” I walked another 100 yards and continued filming. I didn’t know there was a Ukrainian anti-aircraft position, so [it makes sense] he was worried I was filming that. I was arrogant, and he was a bit over the top, but I take more blame. So he arrested me and took me to the Ukrainian Intelligence office. When I got there, I could hear them talk about me, calling me a Russian spy. I yelled: “Do I look like a Russian spy? Look at my Twitter picture!” They looked at it and saw that in 2014, I challenged Vladimir Putin, in a Mammoth Museum in Siberia. Now by the way, it’s impossible to challenge Putin in Moscow, because security will stop you. But he was opening a Mammoth Museum in Siberia, and I look like a professor of mammothology. So I go up to Putin, and all these other professors, and I say: “What about the killings in Ukraine, what about MH17?” Peskov was furious there… But Putin… The cameramen from all Russian TV channels switched their lights on, because they thought the question had been arranged. Putin answered me, he talked rubbish, but nevertheless… So I showed my Twitter picture of me challenging Putin to Vlad. He looked and asked: “You challenged Putin? — Yes!” And then he looked some more on Google, and said: “This is Donald Trump? — Yes! I’m not a Russian spy.” I’ve annoyed Donald Trump so much, Donald Trump walked out on me… And Vlad looked at me and he said: “I think you have an interesting story.” And that’s how I got out and Vlad and I become great friends.

The other story is an apology to everyone in Ukraine. When I met Putin, I had just attended my niece’s wedding. I got off the plane in Yakutsk and was desperately hungry. There was no food on the plane, so I had to stop and eat a kebab. Then I was waiting for Putin, planning to ask him a question. I’m much taller than him. I was going to stand up, but suddenly I had this sense that the kebab was going to come out, so I sat back down. I thought to myself: “You know, John, if you do throw up over Vladimir Putin, you will never have to buy a kebab ever again.” But I managed to keep it down, I didn’t vomit over the president of Russia, and now I regret it and apologize.

Thank you for apologizing for that. I regret not seeing [you throwing up all over Putin] recorded live…

Three hours later, there was a second event Putin was doing with the Chinese Deputy Prime Minister opening a pipeline. Putin and the Chinese officials were on the stage, and I was in the audience. Somebody came up to me, punched me (shows a punching move) silently, completely silent, and walked off. “Putin didn’t like the question, mister Sweeney,” he said it. That’s what it’s like asking Putin a question.

The other day, I went to Kherson Police Station and interviewed a lovely Ukrainian guy called Sasha. He spoke about being tortured with the phone, which is when they wind up hand-cranked military phone, and take the phone off, and they put the clips on your ears, your fingers, and toes, and they shock you. And you can’t do anything because your hands are floating on your back. The poor fellow, Sasha cried as he was taking us around. Then we went to a second place – the cells underneath the main police station in Kherson, and it was really dark there. In the basement, we found something called an “elephant”… It is a nickname for the Soviet-era gas mask, a long green face with big lenses, and then you have the corrugated trunk, the breathing tube, looks like an elephant’s trunk, and then it goes into a filter… I first came across this 23 years ago in Chechnya when I did the radio documentary for the BBC about the Russian army’s torture of Chechens. What they did was tightening their hands behind their backs, putting the gas mask on the face, and then they would squirt the CS gas up the nozzle into the gas mask, so people would start drowning on their own tears. When I saw these gas masks in Kherson, it triggered the memory of that. They’ve been using this torture method in Ukraine. They’ve used the gas mask, the elephant, in Izium against Ukrainians before it was liberated. But what matters here is not the individual method – the elephant or the phone – but the pattern. The pattern has been going for 23 years, according to my own knowledge… Massive use of torture, on a massive scale — it’s a pattern, and it’s a system, and it’s part of Vladimir Putin’s system of keeping control, keeping power, through violence.

And then there is also violence against women.

Yes, it was rape on a massive scale and also the castration of Ukrainian soldiers. I’m uncomfortable with using the word “genocide” because I was brought up when it specifically meant something like the mass murder of the Jews. Still, the meaning has become broader in terms of destroying Ukraine and Ukrainians in terms of the cultural relationship.

Do you think there is hope that somebody can come after Putin because, for example, Navalnyi is, in the same way, imperialist and xenophobic?

Yes, he was so… How does this end? It ends when Russia leaves Ukraine, and I think the only way that happens is when the Ukrainian Army defeats Russia. And then, I’m hoping, somebody gets rid of Putin. Putin’s war has been catastrophic for Russia. And what they don’t understand — Russia will stand in shame, as Germany stood in shame after the horrors of the Nazi regime. But what they need to do is like Willy Brandt in West Germany — he went to the Warsaw Ghetto and kneeled because he was genuinely sorry about what happened and what his nation had done.

I think for us, Ukrainians, it’s really hard to imagine that because Russians have been committing repeatedly genocide after genocide, and they have never self-reflected in the way that Germany did.

If you tell the West that we’re locked into a perpetual war with Russia, people will be afraid of that. I’m an optimist, you can call me a fool, but when Russia loses the war, it can get better. After it lost the Crimea War, they abandoned serfdom, after they lost the war against the Japanese — they created the Parliament Duma. I hope after they lose this war, they become a sweet liberal democracy. Yes, I’m an optimist, or a fool.

I think many Ukrainians want the disintegration of Russia, and liberation of temporarily occupied territories, which is something very uncomfortable for the West.

So the Americans, in particular, are afraid of this. They have got a specific fear of Iraq 2.0. But if you get rid of Putin, you won’t have a nice liberal Democrat. You can have Navalnyi, who’s a Democrat with a troubled history. You will have chaos, and the possibility of an Islamist Chechnya getting hold of the nuclear weapons. The gossip in Washington D.C. is that the Americans want a Ukrainian victory, but on November 5th next year. On November 4th, there will be an American presidential election. They don’t want the Ukrainians to win too quickly, because if they win, then Putin will fall, and there will be chaos, that’s the gossip…

What do you recommend to journalists, who are coming to Ukraine for the first time now, specifically Western journalists? What should they do to prepare to cover this war?

It’s a huge country, the biggest in Europe, and it takes you time to see the whole situation, but the time here is beautifully rewarded. The country is full of incredibly funny people. I love the Ukrainian sense of humour, which is very dark sometimes. But there’s a wonderful sense of wit, and there are moments of humour, and courage, and resilience, which are extraordinarily beautiful. One of the things I love about Kyiv is that everybody wants to drink beer, but you have to fight the monster. And then, when you read about this tremendous spirit in London during WW2, you can see drinking sessions when the bombs were falling. And there were barns for people who played chess across the battle with the Nazis. All people want to do is to have fun and love life, and live life, and yet they have to fight the monster. So I would say to young journalists, it’s certainly much safer than you might imagine in Kyiv, comparing to the war zone.

The other piece of advice to the British, or any former journalist coming here — is to know two phrases: “Putin Khuilo,” which means “Putin’s a dickhead”, and, certainly, till last year, “God Save the Queen”. And you can get through most Ukrainian checkpoints after curfew if you just go: “Hello, good evening, God Save the Queen, Putin Khuilo,” and they say: “Go, you’re late, but go away.” So that’s the Sweeney’ tip for how to get through the Ukrainian Army checkpoints after the curfew.

And for how long do you opt to cover the Russian-Ukrainian war?

Until I die, or until Putin dies… I hope he does first, I’m a younger man.