In 2023, the Kaniv Nature Reserve will celebrate its 100th anniversary. One of the oldest nature reserves in Ukraine, it is situated not far from Kaniv, on the right bank and floodplain islands of the Dnipro, next to Tarasova Hora Memorial Park. It is home to dozens of rare species of birds and animals. For 30 years, scientists Vitalii Hryshchenko and Yevheniia Yablonovska-Hryshchenko have been studying the local flora and fauna as well as the influence of the Kaniv Reservoir on the reserve’s ecosystem.

A maple, a hornbeam, and an acacia behind the shrubs. You can smell freshness and forest. If you concentrate and close your eyes for a minute, you can hear the chaffinch’s singing, the drumming of a woodpecker, and the noise of the Dnipro. Just imagine thousands of ducks, mallards, herons, cormorants and white-tailed eagles creating the surrounding music together. The further you go into the forest, the more nature you experience: moss, mushrooms, unique birds and insects. The dew leaves water drops on clothes, footwear and cameras. It seems that the forest makes visitors stop and look around. Without a doubt, there is a lot to see at Kaniv Nature Reserve.

Vitalii Hryshchenko has been working in the reserve for about 35 years, and during that time, he has seen hundreds of species of animals and plants. Vitalii is an ornithologist — he studies birds and is engaged with their conservation. He was interested in birds in his school years, and his childhood hobby has grown into professional interest.

“There was a well-known zoologist Lev Kaplanov, who was killed by poachers. He was said to be a zoologist by nature and simply could not be anyone else. I am the same: I can’t do anything else.”

Yevheniia Yablonovska-Hryshchenko also specializes in birds, although she studied microbiology and virology at university. As Vitalii kindly mentions, she betrayed germs during her practice at the reserve in the 2nd year. Here, Yevheniia met her future husband, who then mentored students.

Kaniv Nature Reserve is an object of biodiversity conservation: scientists conserve a variety of organisms from terrestrial, marine, and aquatic complexes, and study changes in nature to maintain harmony across ecosystems.

The reserve has recently been granted an international status as an Important Bird Area, and also has become part of the Emerald Network, a list of areas of special conservation importance that are essential for the conservation of biodiversity in Europe.

The current area of the reserve is a little more than two thousand hectares, which are home to historical monuments, the Scythian settlement, and islands. Rare plants, hundreds of species of birds, and more than 50 species of mammals (including roe deer, foxes, hares, badgers, beavers, moose) live here.

Islands

The reserve consists of three parts: the upland part on the hills of the right bank of the Dnipro; two floodplain islands — Kruhlyk and Shelestiv; and the Zmiyini Islands in the Kaniv Reservoir, formed from the hills during the flooding of the reservoir in 1974-1976.

The upland part of the reserve is often associated with Kaniv dislocations and is called Kaniv Mountains. In the autumn of 1943, 250,000 or more people were killed during the Soviet troops’ crossing the Dnipro in the battle for the Bukryn bridgehead, which was located about 50 km up the Dnipro from the reserve. There is a monument dedicated to those tragic events on the territory of the reserve, on Maryina Mountain.

Sedimentary rocks in this part of the reserve are displaced by an extraordinary force — the older, deep layers are turned upside down (that is why they are called dislocations). Scientists argue whether these are the effects of glacial or tectonic landslides.

In the 20th century, Kaniv dislocations were studied by the main initiator of creating the reserve, a geologist named Volodymyr Riznychenko. Then, the landscapes of the reserve were different — bare (because of active deforestation) hills and ravines. The largest, deepest, and longest ravines in Europe are located around Kaniv. At the end of the 19th century, as a result of soil erosion, fields were eroded, roads were destroyed, and even the Chernecha Mountain, where Taras Shevchenko is buried, was threatened.

Then Riznychenko realized that the only way out was to restore and protect local forests. He proposed to create a national park similar to what was being done in Western Europe and the United States. This is howKaniv Reserve was formed, which now conserves hundreds of species of animals, insects, plants and birds, many of which are listed as endangered species in the Red Book of Ukraine (including black stork, osprey, short-toed snake eagle, saker falcon).

slideshow

Vitalii and Yevheniia never cease to be amazed by the forces of nature and are convinced that it is necessary to stop looking at things solely through the prism of an anthropocentric point of view.

“From the desert that was here in times of agricultural activities, we seemed to move to another dimension, with plenty of plants, where everything abounds, everything blooms. I mean, where there is a minimum of human influence, where nature lives by its own laws, actually, for this reason reserves are created, and restoration of the environment begins.”

If you go down the Dnipro, you can get to the island of Kruhlyk, with large colonies of cormorants and herons. On the island you can see how birds nest. Closer to Kruhlyk, cormorants can be seen sitting on the dead top branches of trees. This kind of leisure is the result of a biological peculiarity of cormorants: they do not have a uropygial gland which is responsible for the secretion of fat to lubricate the plumage and not get wet. Therefore, from time to time, cormorants need to sit on trees or sandy banks with raised wings to dry their feathers — in a “heraldic pose”. On this island, scientists conduct annual surveys to track the dynamics of the number of birds. About two thousand pairs of cormorants can nest during the season.

slideshow

Vitalii Hryshchenko says that a hundred years ago, this island was located in a completely different place. The islands constantly move: during the floods in the spring there are very rapid flows, and while in one place they wash the bank away, in another one they add silt. This way, the island of Shelestiv was formed. There is a whole system of internal bays (“currents”). Both the island and these bays resemble outstretched fingers. At first, there was a spit on which sand and silt were deposited, then it got covered with trees and bushes. In parallel, another spit was formed, which also got covered in vegetation. Then these spits merged to form an island.

“This is what remained from the real, not flooded Dnipro, that is why it has a special value: here we can see what it was like before. Today, the fluid dynamics and the processes are absolutely different.”

Now the dynamics of the formation and displacement of islands has decreased, because the dam retains sand. These dams are called “blood clots”. Every year there was a flood, water flooded the floodplain, and the sand was washed away and accumulated back. Now the dam slows down this process. Therefore, scientists consider the impact of the cascade of hydropower plants to be ambiguous.

According to Vitalii, the regular behaviour of the river has dramatically changed: fish cannot spawn, and a strong discharge of water destroys sandy spits where various birds nest. But some species have benefited from this. In particular, due to constant changes in water level, the ice on the Dnipro breaks in the winter leaving a fairly large, open area. Ducks, gulls, and, white-tailed eagles began to gather here. Now this area is one of the main wintering places for aquatic birds in central Ukraine.

Singing of Birds

“To those who are going there, take plastic bags to protect the optics. Otherwise, you’ll catch a surprise!”

“Can I wear your shirt or something else? Because I’m wearing a formal shirt.”

“Yes, put it on. But it is better to wear a cloak and wash it when you are back. When I register birds, I put on a mask to not breathe it in.”

“Well, if you do not go far inside, it is quite bearable. Didn’t you take a machete?”

“I didn’t take it.”

The expedition lands on an island teeming with cormorants and having a strong smell of their feces, which erodes trees, not to mention clothes. The captain measures the depth of the Dnipro near the bank. He says the water is deeper near Kyiv or Pereyaslav. He is worried about running aground and winding the grass from the bottom on the screw and the rudder blade. He has not been here yet — he says that it is “just like a real expedition, the Amazon.”

Yevheniia makes her way through the woods, constantly looking at the treetops. To get through the thickets, she sometimes needs a machete. The scientist holds binoculars in one hand and a professional audio recorder in the other. At first it is difficult to understand what attracts her so much. The sounds of the forest are quite usual — the noise of trees and wind, the buzzing of insects, and the singing of birds. A few minutes later, the woman exclaims, “A Eurasian blackcap!” She says that only this bird makes such a flute-like sound. A wood pigeon starts to sing along, followed by a nuthatch. Then a chaffinch starts singing.

slideshow

Yevheniia Yablonovska-Hryshchenko has been studying birds for over 20 years, but their singing is of special value to her. The finch is the main hero of her research. This small bird, which is up to 18 centimeters long, can be heard from any part of the reserve’s forest. The voices of the birds are recorded and listened to in order to relax, and they are used as medicine for people with mental disorders. Yevheniia makes records for a scientific purpose: it makes it easier to register birds.

“Watching birds is not an activity for those with weak nerves. Try to see a nightingale! But it is easy to hear it.”

The woman says that even music school teachers are unable to distinguish finch songs by ear. What is the secret? In dialects! We know that the language of Ukrainians from Zakarpattia is very different from the language of, let’s say, people from Kyiv; amazingly, birds have the same differences. The bird’s song is not inherited, it is studied. The Hryshchenkos found out that the dialects of finches were formed twenty thousand years ago. And they can still be observed. The formation of the dialect depends on many factors: the historical background and the environment (mountains, plains, forests).

Mostly males sing. Yevheniia says that the meaning of their songs is simple:

“The idea is the following: get out of my territory, I live here. And you, girl, come here, please, look how beautiful I am. Everything is very simple and pragmatic.”

Finches even have song competitions where they perform the same song to find out who the best singer is. While at the beginning the songs are calm and melodic, closer to the end birds almost shout at each other. But Yevheniia says that a female can reject the loudest singer, because there is a risk that he will be eaten: she looks for a calm and reliable male.

According to the biologist, the hierarchy of birds is determined by singing. The most talented singers that perform the most complex songs dominate. And there are those who can perform only simple compositions, usually young ones. To streamline the analysis of bird singing, Yevheniia uses the division of birds by territory and number. She records everything on an audio recorder.

“It’s sunny, almost still, about twenty degrees. This is the singing of number six, area number six. Yes, a roll call, numbers six and three, and a chiffchaff is here too. A saboteur!”

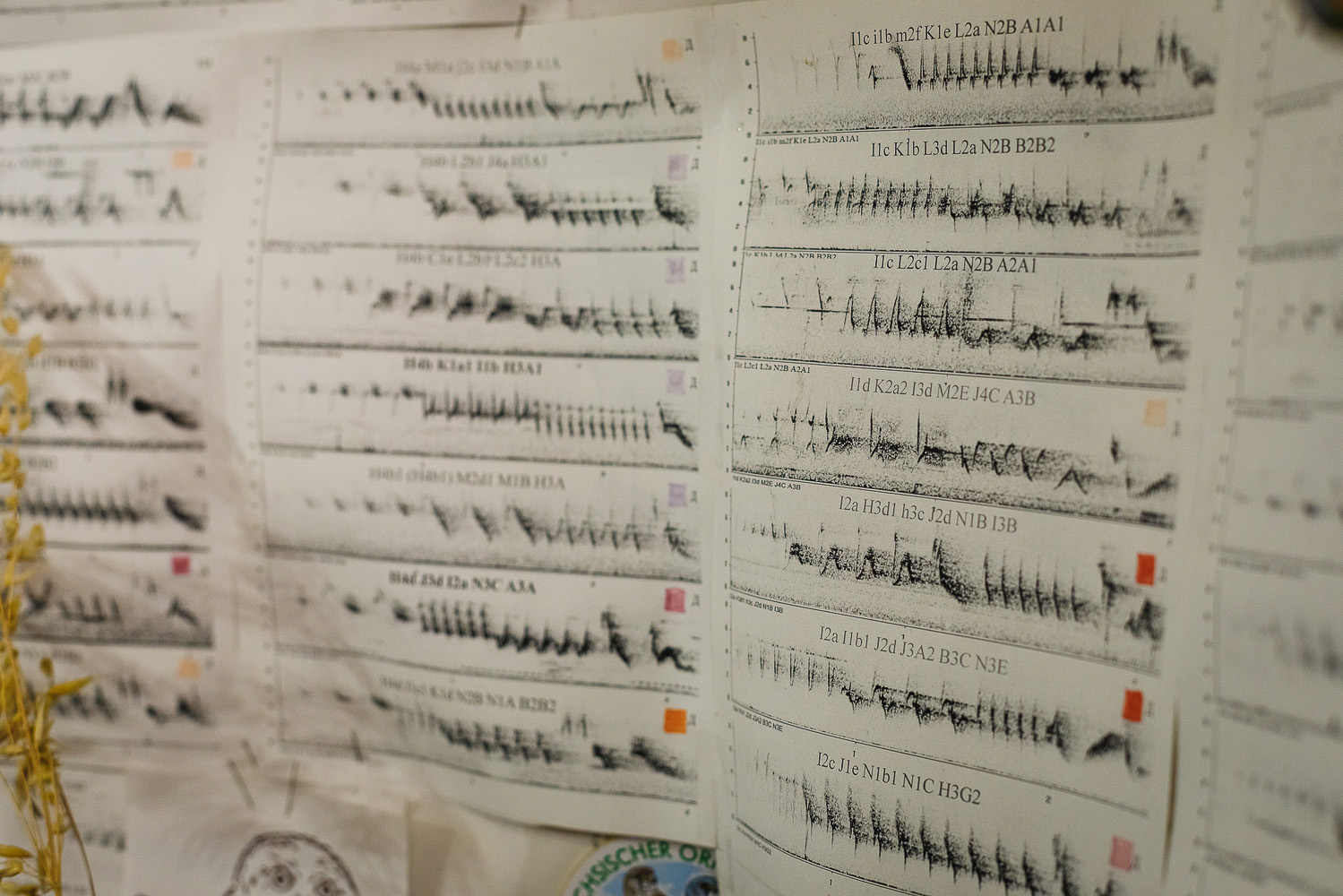

Yevheniia processes these recordings in a laboratory on a computer and receives a sonogram. The scientist analyzes the voices of birds not by ear, but by the frequency distribution over time. Records of birds are sometimes sent to the woman to help determine species. “Actually, this is where the real detective work begins,” says Yevheniia. According to the biologist, bioacoustics in Ukraine is underdeveloped, so she and Vitalii strive to create a national database of bird singing.

Why is it so important to study bird singing? The couple says that these audio recordings can primarily be used as a proof of registration of a certain species. Secondly, it is important to have a national collection of records to know what species we have, and to monitor changes.

“The loss of a bird’s song is a loss of information forever. It will be like a lost language — we can read what is written, but we do not know how it sounded.”

Today, Yevheniia and Vitalii have an extremely large collection of records – seventeen thousand. They say that birds can teach a lot. The most important thing is to be yourself, because “you can’t make an eagle out of a crow or a duck out of an eagle.” Yevheniia adds that the singing of birds helps us learn to listen to the world around us.

“When you start talking to children, you realize that they cannot feel the difference between a nightingale and a sparrow. We live in a visual world, we have lost the ability to live in the world of sounds. This must be learned and taught. Then we will be able to better understand both nature and ourselves.”

The main functions of the reserve are nature conservation, scientific research, and environmental education. Every year students (biologists, geographers, geologists) come here to practice and live in student dormitories. A few years ago, historians and archaeologists conducted excavations in the area, and philologists studied folklore in the surrounding villages.

“We often tell children that the reserve is a place where nature lives the way it wants, according to its own laws, and we do not interfere in its life, but only come to visit it. This is her house, her territory. And we learn to coexist with what surrounds us.”

Yevheniia says that now few people want to connect their lives with science, but she believes that things will get better. She wants to revive the romance of a scientist’s life that existed earlier — travelling, research, far journeys — instead of focusing on money and status. According to the woman, that is why it is extremely important to work not only with students, but also with children — to create a positive image of science, to foster eco-consciousness and caring for nature. Yevheniia notes that it is important to engage with “gentle” education, because prohibitions discourage people. Therefore, scientists seek to show that nature is a vulnerable and delicate structure, and its beauty, unfortunately, is very easy to destroy.

“I can only teach to take an interest in nature. I hope that this year I will be able to tell students what I am telling you. I am very happy that I have such an opportunity, maybe they will also want to do it.”

Water Reservoir. Silent Spring

The main destructive force that affects the reserve, according to the couple, is the Kaniv Reservoir. Under its influence, dislocations are damaged, rocks and paleontological monuments are washed away — reservoirs actually destroyed the ancient Dnipro. The revival of the initiative to create the Kaniv pumped hydroelectric energy storage plant frightens scientists: constant movement of water from the storage power plant can lead to even greater erosion of the mountains. Another danger is the Chornobyl nuclides, which got into the Dnipro and settled in the silt. Due to the movement of water, the PHES will lift this mass of radioactive substances, which will go down the river. Another danger caused by reservoirs, according to biologists, is the washing away of large amounts of fertilizers from fields, which causes outbreaks of blue-green algae. Yevheniia is convinced that Ukraine should focus on its development not in the agricultural sector, but in tourism and recreation.

“Today, they say that the Dnipro is dying. It is dying because of the reservoir. The only thing that makes me happy is that where reserves are created, human influence is getting less significant.”

slideshow

In addition to the problem of the reservoir, biologists are also “hurt” by poaching and chemicals. The couple says that in the spring the security service of the reserve has a lot of work to do. Poachers manage to get to the islands of Kruhlyk and Shelestiv and catch rare fish and birds. And in the summer, synthetic fertilizers pollute the water so much that a tremendous amount of fish dies. If earlier, says Yevheniia, in the spring you could hear a quail from the ground, the cry of a corncrake or the lark singing over the field, now you can only hear silence. And she mentions a book that once made a fuss, “Silent Spring”:

“We already have that silent spring, which was approximately in the 50-60’s in Western Europe. Much has changed in the reserve in twenty years. For example, there was a small island near the left bank of the Dnipro, where birds nested. Now there is no one there.

But Vitalii and Yevheniia, despite all the problems and challenges, consider their activity promising. They run campaigns for preserving primroses, educate people and teach the young generation of scientists, study animals, compile their own collection of bird songs and maintain the Kaniv Reserve as one of the tourist destinations.

“You know, it is impossible to live without the wind in your hair, without the singing of birds, so we do not want to lose this magical world. We realized that if at least one person does not shoot an eagle, then our work has value.”