Karaites are one of the indigenous peoples of Ukraine. They have lived on the Crimean Peninsula since the 13th century. The core of their community is their faith: they recognise the Torah but not religious organisations’ dogmatic interpretations of it because they believe that the reader should interpret it. There are about a thousand representatives left in Ukraine. Most of them live in the occupied Crimea, the rest are spread across Halychyna, Volyn, Slobozhanshchyna, and Pryazovia.

Today, Karaites are one of the smallest indigenous peoples of Ukraine. Karaite communities in Yevpatoria and Simferopol number several hundred people, and in Feodosia there are about a hundred Karaites. Outside the peninsula, there are even fewer members of this ethnic group. The largest Karaite community in mainland Ukraine operates in Melitopol, and the only active kenesa belongs to the small but active Kharkiv community. Several people also live in Kyiv, Halych, and Lutsk.

Karaites have always been a small but influential community. The Kyiv Karaites, for example, at the end of the 19th century comprised just 300 people. But one of the community’s patrons, Solomon Kohen, funded the construction of a kenesa in the heart of the city, on Yaroslaviv Val Street. One of the most prominent architects in Ukrainian history, Władysław Horodecki, was commissioned for the project. The kenesa served the community for fewer than 30 years, as it was withdrawn by the Soviet authorities. Today, this building is known as Actor’s House.

Karaite ethnic identity has only just withstood the test of time: despite variable political upheavals, waves of antisemitism, and the Soviet Union’s antireligious campaigns in the historic Ukrainian lands, Karaites retain remnants of their history and culture.

Where do Karaites come from?

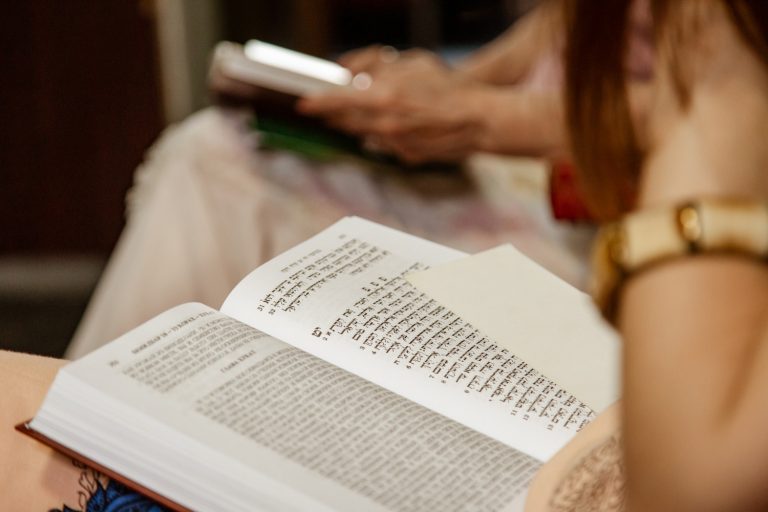

Karaism is an Abrahamic religion that is similar to Judaism but more ‘liberal’. It is believed that it originated in the 8th century in Baghdad (now the capital of Iraq). This movement is sometimes called Ananism (named after its founder, the preacher Anan ben David). He urged people to abandon the Talmud and other intermediary books, to ignore the rabbis’ interpretations, and to instead read and interpret the sacred texts on their own. ‘Karaite’ means ‘reader’ in Hebrew.

Abrahamic religions

They are based on the teachings of Abraham, the original written source is the Old Testament. The main religions are Christianity, Islam, Judaism.The current head of the Kharkiv Karaite religious community, hazzan Oleksandr Dziuba, explains that this approach underlies Karaite beliefs:

— Karaites recognise only the books of the Tanakh: the Torah, the Nevi’im, and the Ketuvim (the Old Testament in the Christian tradition). They profess a faith based on these scriptures without additions, mandatory dogmas, or binding commentaries for everything.

The first Karaite communities in Crimea appeared in the cities of Solkhat (Staryi Krym), Qırq-Yer (Chufut-Kale since the 17th century), and Caffa (today known as Feodosia). This is evidenced by the Karaite necropolises from the 13th-14th centuries. The necropolis on the territory of the cave city of Chufut-Kale is one of the most famous. There are several versions of how Karaites got to Crimea and how the ethnogenesis of this community came to be. The most common of these combines two theories. According to the first theory, Semitic, the followers of Karaism migrated to the Middle East and Byzantium from the Abbasid caliphate (Iraq) after the 8th century. Later, in the 13th century, this religion came from there to Crimea, which at that time belonged to the Khazar khaganate, and spread across the peninsula. United by a common religion, the Karaism adherents formed a new ethnic group.

The second is the Khazar theory. According to it, Karaites are the descendants of the Khazars, Alani, and nomadic Turkic peoples, who converted to Judaism, but retained certain attributes of the Turkic culture, such as linguistic features, cuisine, and clothing.

— Karaites, as well as Crimean Tatars and Krymchaks, are indigenous people of Ukraine. Karaites have no homeland other than Crimea, which was actually seized from us.

slideshow

The main occupations of Karaites in Crimea were cattle breeding, trade, and handicrafts. It is also known that Karaites were traditionally engaged in military affairs. According to Oleksandr Dziuba, the military skill of Karaites impressed Grand Duke Vytautas of Lithuania:

— As skilled and brave warriors, Karaites were taken over by Vytautas the Great during the campaign in Crimea at the end of the 14th century. He brought several dozen Karaite and Tatar families and settled them in his capital Trakai, in border towns, and in other important centres of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania.

Later, Karaites also lived in Vilnius, from where, according to one version, they went to Halych, Lutsk, and Belarus. According to another version, 80 Karaite families from Solkhat, Mangup, and Caffa came to Halych in 1246. It is believed that they were invited by Kniaz Danylo of Halych with the permission of Batu Khan. In this way, the medieval rulers tried to develop trade between the Kingdom of Halych and Volyn and the eastern principalities, which were then subordinated to the Golden Horde.

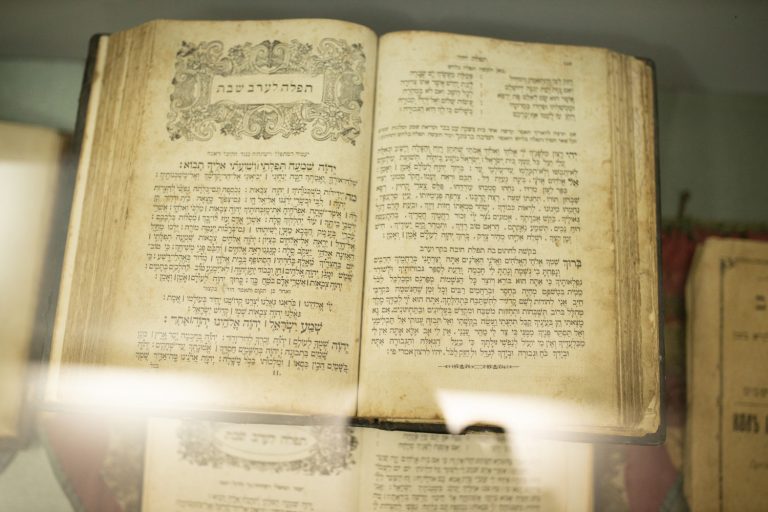

Settling in new lands, the first thing that Karaites built was a ‘kenesa’, a prayer house. This word comes from Biblical Hebrew and means ‘meeting house’ (beit knesset). ‘Synagogue’ is translated as ‘assembly, community’ from Greek, and the French word ‘église’ to denote the church also means ‘assembly’. The board of a Karaite community consisted of three people in any historical period: the hazzan, the gabbai (the elder who is responsible for the economic part), and the shamash (equivalent of a deacon in the Orthodox Church), assisting the other two.

Karaite tobacco. Emergence of a community in Kharkiv

In the 19th century, the development of Karaite communities and their culture experienced revival. During this period, the Crimean Karaites began to grow tobacco and produce tobacco products:

— The sale of tobacco contributed in no small part to the emergence of new Karaite communities, the opening of kenesas, and the publication of Karaite periodicals.

Thus, in the 1840s, a Karaite community appeared in Kharkiv. Here they settled in the area of Rybna (now called Kooperatyvna), Kuznechna, and Netechenska streets and Podilskyi Bridge, where at that time lived mostly craftsmen and merchants.

Karaites quickly established themselves in the city and occupied their niche in the tobacco market. Karaite tobacco shops were in great demand in the Russian Empire. It was Karaites, the brothers Solomon and Moses Kohen, and Mordecai Shyshman, who owned the Empire’s three largest tobacco factories.

In industrial Kharkiv, the Karaite tobacco business developed rapidly: at the beginning of the 20th century, the number of workers in these industries exceeded 200 people.

In addition to successful entrepreneurs, there were many figures in the community who held administrative positions and practised medicine:

— In the language of the Holy Scriptures, ‘rofe’ is a doctor. And Karaite doctors were very skilled. And now the Kharkiv Karaites support this tradition as well. There are many doctors in our community.

According to Oleksandr Dziuba, richer members of the community have always supported less fortunate Karaites. For example, they contributed to young girls’ dowries, married them off, and financed education. They also put the unemployed back on their feet:

— There were no beggars among Karaites. If someone begged, it was considered a disgrace to the whole community. He was either given start-up capital or engaged in some Karaite business.

Kenesa

Prosperous Karaites were also patrons and invested much of their wealth in the cultural development of the community. Thus, in 1853, the Kharkiv community already had a prayer house.

Initially, the Izmailovs’ house at the corner of Podilsky Alley and Kuznechna Street was rented as a room for a kenesa. Later, Karaites bought it up and demolished it, and built an authentic Karaite kenesa in its place. The construction was financed by 36 Karaite families, and the funds were raised by the community’s gabbais, the Khandzhi brothers. Their houses on Kuznechna Street, a few blocks from the kenesa, have been preserved to this day.

Oleksandr explains that Karaites deliberately chose the location near the houses, tobacco shops, and factories where they lived and worked:

— According to the Karaite tradition, the house of worship shouldn’t be too far from the community’s place of residence, because, for example, on Saturday (the Sabbath) it is forbidden to use transport and even pay for travel, due to the fact that those who follow Karaite traditions do not use money on Saturday. Therefore, Karaites usually built a kenesa where they lived.

Sabbath

For Karaites, as well as for Jews, the day from sunset on Friday is the Sabbath, the seventh day of creation during which one cannot work.The Kharkiv kenesa is an example of the Karaite religious architecture. The building combines elements common to both synagogues and mosques. The facade of the kenesa is decorated with traditional Karaite ornaments. The influence of oriental architecture is noticeable in the combination of geometric shapes with curved forms and flower images, and the prayer house itself is oriented to the south, i.e. towards the holy city of Jerusalem.

slideshow

Services are traditionally held three times a week. Karaites should be barefoot at the service, men in a fez, and women with their heads covered. They prayed separately: men in the prayer hall on blankets, and for women there was a separate balcony:

— Women could see and hear everything that was happening in the hall, but men could not see and hear them inside the hall.

Next to a kenesa, a midrash was usually built, that is, a theological school where children were taught Biblical Hebrew and other subjects.

The Kharkiv hazzan adds that Karaites played an active part in social life and that they were respected as professionals. For example, Mark Kalfa, an early twentieth-century Kharkiv tobacco magnate, was a spokesman for the Duma (council) of the city. It was also a Karaite who designed the city’s first sewer system: engineer Danyil Cherkes was invited to Kharkiv after he had successfully implemented a similar project in Yalta.

Karaites in the Soviet Union

Military affairs remained a traditional occupation of Karaites in the early 20th century. Until 1917, many Karaites were officers of the Imperial Russian Army and took part in World War I, so during the Civil War they sided with the Whites. Their defeat, according to Oleksandr, caused a demographic crisis:

— Someone was shot, someone emigrated, someone perished, someone died of typhus. A whole generation of Karaite brides were left without men. They were brought up in such a way that they married only their folk.

By 1917, about 15,000 Karaites had lived only on the Crimean Peninsula, and in ten years their number decreased by more than half.

The political upheaval caused by the October Revolution led to a decline in the Karaite population in the west as well, but later. Traditionally, Western Karaite communities were small, with almost no mixed marriages. However, these communities actively developed the Karaite culture. There were historians, poets, writers, and scientists. Because of this, they began to be persecuted by the Soviet authorities, who gained control of these territories in 1939. Therefore, after the war, when the borders were being redefined, many young Karaites left for Poland, and traditional Ukrainian Karaite communities gradually disappeared as a consequence. As a result, according to the 2001 population census, only 1,196 people in Ukraine identified themselves as Karaites.

As part of the Ukrainian SSR, Karaites did not have the opportunity for cultural and religious self-expression. Oleksandr Dziuba says that as part of the fight against religious cults, the Soviet authorities dissolved communities, closed kenesas, national-cultural societies, and schools where the teaching language was Karaite:

— All structures where Karaites had an opportunity to unite were closed. So they only got together with family and friends. At the same time, the number of marriages with representatives of other religions and ethnic groups increased, and assimilation took place.

Karaite religious leaders also disappeared in that period. The last Karaite spiritual leader was Seraya Shapshal. He was forced to renounce his status and declare himself a secular historian. Otherwise, he would have been imprisoned, like the hazzans of the Lutsk and Simferopol communities, Yeshua Leonovych and Yakiv Shamash.

Community revival. Gabbai and hazzan

In Kharkiv, the Karaite community ceased to exist in 1929. The kenesa with its entire inventory, and all of its books and documents, was handed over to the organisation of militant atheists, who turned it into a museum-club. During the Soviet era, the building underwent significant changes: a second floor was put in, the windows and tablets that crowned the kenesa disappeared, and the related buildings were abandoned. Members of the community had to adapt to the new living conditions: they no longer married exclusively Karaites, enrolled their children for the All-Union Lenin Pioneer Organisation, and rarely spoke of their Karaite origins.

The revival of the Kharkiv Karaite community began in 1994, after Ukraine had gained its independence. Then, on the initiative of the famous Kharkiv composer Valentyn Kapon-Ivanov, the Karaite national-cultural community ‘Karai’ was created, and in 2006 Valentyn managed to return the kenesa to Karaites. The composer researched the Karaite music, searched for the old records, printed or handwritten notes, and created modern Karaite compositions in many genres. Oleksandr believes that there is a certain symbolism in the fact that it was Valentyn Kapon-Ivanov who began the restoration of the Karaite culture in Kharkiv:

— The first Kharkiv hazzan in the 1860s was his ancestor, merchant Abraham Kapon from Yekaterinoslav (now Dnipro). That’s how it works, that one person was the first leader of the community, and another revived this community in 150 years.

On regaining possession of the kenesa, the community began to recover. Today there are about 30 people in the Kharkiv Karaite community. It is open to all, so there are members of different nationalities, but most are ethnic Karaites. Oleksandr says that the older generation of the Kharkiv Karaites knew about their cultural heritage from childhood, so they remember certain traditions, rituals, phrases in Karaite. However, there are those who have only recently begun to learn about the Karaite culture.

slideshow

The gabbai (the elder) of the Kharkiv kenesa, Oleksandr Makhlaiev, who is also its second hazzan, was born in Minsk, Belarus, and almost immediately after his birth, the family moved to Kharkiv. Oleksandr says that he learned about his Karaite origins only in 2007:

— I contacted my brother via Skype and he told me that our grandfathers, who were cousins, were both pashas.

Pasha

A respectful rank in the Ottoman Empire, the equivalent of governor or general.According to Oleksandr, strangely his life was based around kenesa before this. For example, forty years ago, he received his driving licence in one of the houses associated with the kenesa, which he recently purchased for the Karaite community. And in 1998, Oleksandr often visited his friend, the deputy director of a transport company, on the second floor of the kenesa and always marvelled at the beauty of the old building.

However, Oleksandr Makhlaiev decided to join the Karaite community only in 2012. Since then, he has been the gabbai of the Kharkiv prayer house, solving household issues every day. He heats the premises of the kenesa, monitors the technical works, and is trying to fix the water supply. As the second hazzan, sometimes he also holds services.

Oleksandr Dziuba has been a hazzan of the Kharkiv kenesa since 2012. Today he is the only hazzan in Ukraine, a spiritual leader of Karaites, who conducts mass, studies the Torah and the traditions of Karaites.

Oleksandr is a converted Karaite. In 2005, he and his wife visited Yevpatoria and went to the only kenesa in Ukraine at the time, where they got acquainted with the culture and history of the Crimean Karaites.

— This story impressed me. Someone said that the best journey is the one that has this existential element, one from which you return a different person. I became interested in Karaites because the main principle of the Karaite faith is to read the Torah carefully and not rely on someone else’s opinion.

Since then, Oleksandr has begun to delve into the Karaite culture. His teacher (‘raf’ in Karaite) was Oleksandr Babadzhan, the hazzan of the Simferopol kenesa. He recounts how, little by little, he was becoming increasingly convinced that the difference between Judaism, Christianity, and Islam lies only in the interpretation:

— When we read only the Torah, the Gospel, and the Quran, we come to the conclusion that it is about the same thing. My great-grandfather was an Orthodox priest. And I don’t think that he and I belong to different religions. We just interpret the same text differently.

Now Oleksandr Dziuba serves in the Kharkiv kenesa and speaks about the Karaite history, culture, and traditions. He says that this knowledge was gathered in small pieces from the Karaite religious literature and periodicals that were published before 1917. According to Oleksandr, it is equally important to preserve secular traditions, such as national dishes, songs, dances, the Karaite language, proverbs and sayings. Although there are almost no native speakers in the community, they are trying to preserve and pass on to future generations the words and phrases they still remember.

Kharkiv hazzans admit that the Karaite community revival is not easy. First, during the seventy years of Soviet rule, many traditions were disrupted, and secondly, the restoration of the kenesa to its original form requires significant investment. The occupation of Crimea is another hurdle, as it cut off Karaites from the origins of their culture and its most powerful centres.

Today, the Kharkiv Karaites have the opportunity to communicate online with the communities in Simferopol, Feodosia, and Yevpatoria and do not give up hope for a future meeting. They also keep in touch with Karaites around the world:

— The Karaite world is like a small town where everyone knows each other. In any country where there is a Karaite community, we actually know these people. Our ancestors knew their ancestors and so on. We communicate with the Karaites of Crimea, Turkey, Israel, the USA, France, Poland, and Lithuania.

So let many traditions be forgotten, and let Karaites together restore those they remember. Oleksandr believes that this is enough to preserve the Karaite culture:

— There is a very accurate saying: ‘There is no Karaite without the Torah’. This means that religion is the core, the backbone on which everything rests. If this is removed, everything begins to fall apart, as proved by these seventy years of Soviet rule. The Karaite community will continue to exist if the religious tradition is restored, if Karaites gather here every Saturday, study the Holy Writ and revive the traditions.

Karaites of Halych

In the 17th century, 24 Karaite families lived in Halych, almost all of them on Karaimska Street. It is not known exactly when the Halych kenesa was built, but we know that there was a hazzan there at the beginning of the 18th century. The building combined the Moorish style with the Baroque elements. It was painted with the Torah quotes on the inside and Psalms quotes on the outside.

The kenesa was closed in 1959. Initially, it served as a warehouse, and in 1985 it was demolished together with several neighbouring houses to build the first high-rise building in Halych. Families who lost their homes because of this were then given apartments in this nine-storey building. Among them was the family of Semen (Shymon) Mortkovych, now the oldest member of the Halych Karaite community.

Semen’s parents died early, and he and his older brother were raised by aunts. One of them, Yanina Yeshvovych worked in a bank and was the informal head of the Karaite community. She kept contact with the Karaite communities in Kyiv, Yevpatoria, and abroad.

Semen Mortkovych studied at the road transport technical school, served in the army in Orenburg, and then returned to Halych, where he worked for a long time as a driver of the local head of the district union. In Halych, he met his future wife, a local, Tamara. She was his neighbour and his aunt’s colleague. Tamara says that fate brought them together during difficult periods of their lives: Semen was recovering after the removal of a cancerous tumour, and Tamara herself was raising two children after the death of her first husband. She says she fell in love with Semen for his kindness and willingness to help. According to her, Semen was loved by everybody in the city for these traits:

— He was very active, he was very friendly with Ukrainians, he was respected. When someone needed something, he would immediately start searching, get a lorry and go to bring something to someone. And he was very reliable.

slideshow

Probably because of such friendly relations between the Halych locals and Karaites, the latter were warned that the kenesa would be closed, so they managed to take away all the cult items: religious books, menorahs (seven-branched candelabra), old prints, ceremonial utensils for the Kiddush (blessing), and the hekhal, a kind of altar in the kenesa. At first, members of the community hid the sacred objects in their homes. Semen had two menorahs in his garage, and his aunt took the Torah.

Some of the items were later given to the community in Yevpatoria, and what was left later went to the Museum of Karaite History and Culture. The idea to create a museum as a physical centre of Karaite culture had existed for a long time. It was especially actively popularised by Semen’s aunt Yanina. The National reserve ‘Davnii Halych’ (‘Ancient Halych’ — tr.) helped the Karaite community to realise this dream. Employees of the organisation first researched the Karaite cemetery: they created a gallery of tombstones, translated inscriptions from Old Hebrew into Ukrainian and published the catalogue ‘The Karaite Cemetery near Halych’. In 2002, when the Halych Karaite branch numbered eight people, ‘Davnii Halych’, led by Ivan Yurchenko, organised an international conference ‘Halych Karaites: History and Culture’, which became the starting point for the museum, which was opened in 2004.

Artifacts from Lithuania, Poland, and Ukraine are kept here: printed and handwritten religious books, prayer robes and a scarf of a hazzan, a stamp and calendars from the Halych kenesa. Photographs and personal documents of the Halych Karaites, such as birth, marriage, and school certificates, were collected in a separate exhibition.

slideshow

In the exhibition for everyday life of the Halych Karaites, there are special utensils for preparing Karaite dishes for the celebration of Easter (Passover, ‘Tyshbyl-Khydzhy’, the holiday of unleavened bread). In particular, there are ‘talky’ and ‘kesler’, utensils used for making the dough for the traditional Karaite Easter bread.

Semen explains that Karaite cuisine is similar to Jewish, but has a number of differences and unique dishes. This demonstrates the relationship between the Jewish and Turkic origins of the community. For example, Karaites have a slightly different recipe for matzah:

— Our matzah is baked, you know, not like the Jewish one, which is flat. During the holiday, they are not free to consume flour or milk. But we are allowed to and have this round matzah. It is made from water, milk, and sour cream.

Tamara Mortkovych says that she studied Karaite cuisine while watching Semen’s aunts. The Mortkovych family used to make a traditional potato pie with meat, which is called ‘bulbuliak’ by the Karaites, and another special dish was ‘kybyn’, a pie stuffed with rice, onions, and duck meat. Tamara recalls that she once treated the employees of the Israeli embassy in Ukraine to such a delicious kybyn that she had to write down the dish’s recipe for them.

In Crimea, Melitopol, and the Lithuanian Karaite centres, ‘et ayaklak’, traditional meat pies, are cooked. Representatives of the Melitopol community believe that their pies deserve to be included in the UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage List, and are working to get Karaite pies there.

Today, Semen is the only Karaite remaining in Halych, but this community has managed to preserve its history and traditions and pass them on to future generations thanks to the artifacts collected in the museum.

supported by

Material prepared with support of United States Agency for International Development (USAID)