In Kharkiv, two apartments in historic buildings have been redeemed. A prominent critic, essayist, and linguist Yurii Sheveliov lived in one of them, and writer Petro Lisovyi lived in the other. These apartments have not been redeemed for the sake of ‘luxury’ refurbishment: but for literary residencies that have already started operating in these apartments today. Writers, literary researchers, and other art activists settle in the historic apartments for a few weeks at a time, to create new cultural works in Kharkiv.

It became known in 2019, that Sheveliov’s apartment was for sale. The Literary Museum, one of the most dynamic and interesting cultural structures in the city of Kharkiv, immediately became interested in purchasing his apartment. The deputy director of the museum, Tetiana Pylypchuk, says:

“At that time, the wonderful Kharkiv publisher and researcher Oleksandr Savchuk was working on the two-volume Memoirs of Yurii Sheveliov ‘I — me — for myself’. In the books, Savchuk found a plan of the apartment where Sheveliov lived. Our museum architect, Serhii Kangelari, looked at the plan and said: ‘This apartment is for sale’.”

In order to return Sheveliov’s name to the urban context and to develop Kharkiv’s status as a centre of modern literature, the LitMuseum team began looking for opportunities to buy the apartment of the famous linguist.

Apartments with the breath of history

Yurii Sheveliov is one of the most prominent figures of Ukrainian culture in the 20th century. He was born in Kharkiv during the time of the Russian Empire, and in the 1920s, he became a critic and linguist. He was lucky to escape Stalin’s repression, although the NKVD forced him to cooperate. During World War II, Yurii Sheveliov remained in occupied Kharkiv and later managed to leave for the West. There he gradually became one of the most prominent Ukrainian diaspora critics, essayists, linguists, and Slavists. Sheveliov was among the organisers of the legendary MUR association, and he wrote dozens of important books and articles. Tatiana explains:

MUR

(Ukr. acronym for Mystetskyi Ukrainskyi Rukh, ‘Ukrainian Art Movement’) It was the Literary Association of Ukrainian writers in German emigration in the 1940s. It included Ivan Bahrianyi, Yevhen Malaniuk, Viktor Petrov, Ihor Kostetskyi, and others.“He is not only a linguist and literary critic. He has also left unique, extremely honest memories of himself and his time. There is a lot about Kharkiv in these memoirs, as well as in his essays. I think these are the best memories and essays about Kharkiv, although they do not only contain pleasant and complimentary things. We should be happy to have such a thinker.”

The fact that Sheveliov lived under German occupation and even worked for the Kharkiv-based occupation newspaper Nova Ukraina, as well as for the local administration, became a source of heated controversy and scandal. Sheveliov was accused of collaborating with the Nazis. Eventually, in 2013, a commemorative plaque on the house where he lived was smashed.

Tetiana Pylypchuk often takes guests through this part of the old centre of Kharkiv. There are many historical sites associated with the cultural boom of the 1920s and 1930s.

“Here on Sumska Street, 5, as we found out, there was indeed a famous Coffee Shop Pо́ka where writers gathered for Turkish coffee and French waffles. This was the favourite ‘coworking space’ of the leading Ukrainian futurist Mykhailo Semenko.”

A little up the street, there was the Berezil Theatre of Les Kurbas. Next was the ‘VUTSVK News’ editorial office of the All-Ukrainian Central Executive Committee. Here, in the unheated rooms of a former house church, the future leaders of the Executed Renaissance, young and still little-known writers at that time, were partying.

Executed Renaissance

It was an experimental period in the history of Ukrainian culture when first-rate works in various genres of art were created and charismatic cultural leaders appeared (Mykola Khvylovyi, Vasyl Yermilov, Les Kurbas, and others). The period ended with mass repressions by the Soviet authorities.“This place, known at that time under the witty name ‘Literary Fair’, was edited by the State Publishing House of Ukraine. Literary life abounded, and this contributed to the fact that the young Yurii Sheveliov discovered Ukrainian culture. It was a distinct culture, not the provincial one like what was presented in the 1910s, but a new, pretentious, lively, and bright one.”

Sheveliov lived in the famous house on Sumska known as Salamandra (that was the name of the insurance company that built it in 1914-1916). Salamandra occupies a whole block, and people come through the Sheveliov entrance not from Sumska itself, but another street, Rymarska.

“The apartments in this house were pretty comfortable. The Sheveliov family bought a quite large apartment here, about 150 square meters.”

Sheveliov’s father was a general in the Tsar’s army and thus could afford expensive housing. But then he left the family, and the mother and son began to have financial problems. They had to rent out some of the rooms. And with the establishment of the Soviet regime, the apartment was turned into a ‘communal’ one, so the Sheveliovs had to settle in the former room for servants. Salamandra, the place where Yurii Sheveliov as a man of imperial culture chose the Ukrainian identity instead was naturally a matter of interest for LitMuseum.

In 2020, another apartment was put up for sale. The one in the legendary Kharkiv Slovo Building where a journalist and science fiction writer Petro Lisovyi (his real surname was Svashenko) once lived. What is Slovo? It is a large residential building on Kultury Street that was built specifically for Ukrainian Soviet writers during the 1920s and 1930s, according to a constructivist project (with some influences of modernism and art deco) by Mykhailo Dashkevych.

To a large extent, the writers themselves financed the construction of Slovo, creating a special cooperative for this purpose. The rest of the money was ‘contributed’ — of course, from the state budget — by Ulas Chubar, the chairman of the Council of People’s Commissars (Government of the USSR). The house is C-shaped when looked at from above. Dozens of the most prominent writers, translators, critics, and other people of culture lived here in the 1920s and 1930s: from Mykola Khvylovyi to Mykhailo Semenko, from Pavlo Tychyna to Les Kurbas. The Slovo Building became one of the symbols of the rapid development of Ukrainian literature in the 1920s and 1930s that largely took place in Kharkiv which was the capital of Soviet Ukraine at that time.

“Many artists with different ambitions and ideas came to Kharkiv back then. Nevertheless, they were united by the desire to change the world, to make it better. That is why a new centre, new fascinating projects, and constructivist architecture appeared. Freedom, experimentation — that’s what I love about that period. Soviet totalitarianism was not yet established at that time. A unique environment was created.”

The ‘workshop’ nature of Slovo was felt during the active phase of Stalin’s repressions, the so-called Great Terror. It turned out to be much more convenient to arrest and control writers en masse when they lived in the same house. It was here that a loud shot that ended the life of Mykola Khvylovyi was heard.

Gradually, writers disappeared from this house: some were arrested, others left, died, and new writers no longer settled here. Slovo became an ordinary house. During the independence period, there was an active interest in the events of the 20s and 30s, archives about the realities of that time became more accessible. The house became a cult monument for Kharkiv.

Launching literary residencies

The idea of organising cultural activity in the Slovo Building had been brought up regularly for quite some time There was even a concept to arrange a museum here. However, according to Tetiana Pylypchuk, it was abandoned because there was too little authenticity preserved in the house. There was an intention to organise a cultural hub, but it was not possible to buy the rooms. However, the initiative group always wanted to diversify the tragic-memorial image of the Slovo building and show that not only did the literary generation perish there, but culture was also being created there: bohemian entertainment was taking place, and interesting people were having fun.

In 2020, the LitMuseum team got acquainted with businessmen Andrii and Mykola Naboka, a father and son. Entrepreneurs were interested in the history of the city and its literature. They eventually bought Peter Lisovyi’s apartment in Slovo and Yurii Sheveliov’s apartment in Salamandra. In both cases, it was decided to create a space for a literary residence, to be visited by writers from other cities and countries, to strengthen interregional and international literary interaction and the presence of Kharkiv in literature in general.

Literary residencies are a common phenomenon in the world. They are often arranged in apartments with a relevant history. For example, in Prague, there is the “Praha město literatury” residency (‘Prague is a city of literature). Writers and translators from all over the world go there for two weeks to work on a proposed project. Then, having already published the texts written there, authors note that they were written at the residency. This residency is a project of the Prague City Library, and its participants live in an apartment in Barrandov (an area famous for the film studio of the same name) where the Slovak writer Ladislav Mňačko once lived. The library also holds meetings with these residents in various cultural locations around the city centre.

“For writers who often have to not only write, but also work somewhere, this is an opportunity to be just writers for a while, and not also editors, journalists, and so on. It is the opportunity to plunge into the city, the country.”

slideshow

The literary residency in Kharkiv was established in 2018, in cooperation with the Ukrainian PEN, the Literary Museum, and the Kharkiv Regional State Administration. At first, the apartments were rented out to participants, but in 2020, when Andrii Naboka bought the houses of Sheveliov and Lisovyi, everything changed.

Ukrainian PEN

A non-governmental organisation that was established to protect freedom of speech and copyright, and it promotes the development of literature and international cultural cooperation. It is part of the network of national centres of the International PEN.Why did the artistic history of Kharkiv appear to be important for a businessman? Tetyana Pylypchuk explains:

“For the Naboka family, this is also their history, the return of memories, and associations. I think it is also important that Andrii is a graduate of the Kyiv-Mohyla Business School. His education gives him a broader vision, and it shows him that business is not just about making money. The Sheveliov and Lisovyi apartments were for him, apparently, about the meanings and discoveries. Initially, he became interested in the history of the Slovo Building because he thought that little was known about it in Ukraine. He intended to buy a room there and arrange some museum space. Then he was advised to contact us.”

The apartments are taken care of by a group of activists including owner Andrii Naboka, members of the Literary Museum team (Teiyana Pylypchuk, Lidia Kalashnykova, Oleksandra Tesliuk, Oleksii Yurchenko, and Olena Ruda), writer Serhii Zhadan, publisher Oleksandr Savchuk, and curators of residencies Mykola Naboka and Ivan Senin.

In 2021, the location of the Kharkiv residence Slovo started operating. Lisovyi’s apartment in Slovo was in more or less residential condition, so the first residents began to arrive there in January.

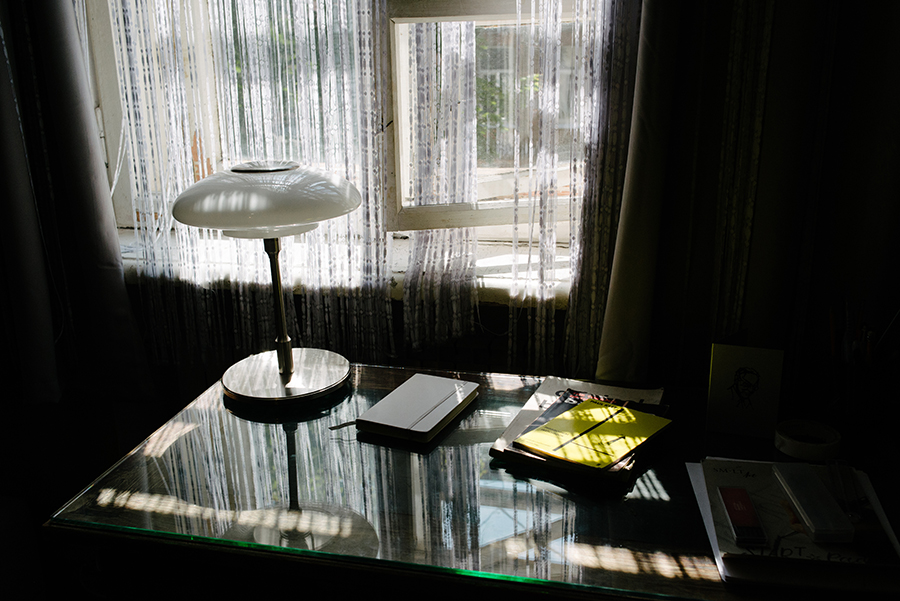

“There is an interesting experiment: we give our writers who come to the residence a right to choose where the study will be in this apartment. Everyone chooses the same place: in the corner room. They feel comfortable there. We suspect that this is where Petro Lisovyi’s office was located. Everyone says that the apartment is very comfortable for writers. It is no coincidence that Slovo was built, speaking in modern language, as a kind of author’s cohousing space.”

Serhii Zhadan presented his personal desk to this residence. He also curates events or kvartyrnyky (Ukr. ‘home concerts, poetry sessions etc’ — tr.).

However, it was impossible to launch the residency in Sheveiyov’s apartment on Sumska Street immediately.

Can you imagine a Soviet komunalka (Ukr. ‘communal apartment’ — tr.)? That, in fact, was what it was, and completely in a neglected state. And so the restoration process began there. Well, it’s not a classic restoration. But we tried to work with the space as gently and accurately as possible. Layer by layer, the traces of repairs and changes were carefully removed. Fortunately, these repairs were minimal and cosmetic as no one wanted to seriously invest in the komunalka.

Removing the wallpaper, we managed to reveal the walls as they were in the days of Yurii Sheveliov. So there were different layers left in different parts of the apartment as if symbolising different historical epochs. Then there was modern furniture against the backdrop of all this.

“We preserved Bergenheim tiles, doors, and joinery as much as possible. I don’t know yet, we will see what the apartment looks like in the winter. We may need to restore the windows. Our architect offers another solution: glass screens to preserve the authentic arched windows. In general, architect Serhii Kangelari enjoys working with Sheveliov’s apartment, He also lives at the Salamandra House.”

Bergenheim tiles

The famous Bergenheim tiles of the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century, were produced at the factory of the Kharkiv businessman, Edward Bergenheim, a native Finn.For the residents’ comfort, the residential part was separated from the public space where kvartyrnyky and other events are held. The large area of the apartment provides many options. You can get to such public events by registering through the Facebook page of the residence.

slideshow

Residency projects

The residential part of Yurii Sheveliov’s apartment has been functioning as a residence since May 2021, and they are still working on the design of the public space. Yurii Andrukhovych was the first resident in Sheveliov’s apartment.

“He was interested in radio. He wrote a hoax for one project about radio programs of the 1930s. We picked up our materials plus materials from the Korolenko Library for him. Yurii Andrukhovych was gaining vocabulary and atmosphere. In general, the appearance of Andrukhovych in Sheveliov’s apartment was a significant moment. We recall how in the 1990s, it was Sheveliov who supported Andrukhovych’s ‘Recreations’ novel with an authoritative approving response. They were in touch after that.”

In August, British director Jonathan Ben-Shaul arrived at Sheveliov’s apartment. Here is how he describes his project in Kharkiv:

“I am working on a film that combines dance and architecture. It will explore our constant interaction with architecture, conceptualize it through dance. One part of the film will consist of interviews, the other part of the film will be composed of movement.”

To explain his understanding of the interaction between dance, theatre, and architecture (the common phraseology of ‘dancing about architecture’ is clearly taking on new meanings!), Jonathan Ben-Shaul organised a kvartyrnyk. At the entrance, the guests were met and taken to the apartment by Mykola Naboka who collaborates with Ben-Schaul on his project and also demonstrates an interesting ‘architectural’ adaptability. The next day after the kvartyrnyk, the authors of the project made a short ‘expedition’ to one of the Soviet cinemas in Kharkiv: to shoot, dance, and study the peculiarities of this Soviet modernism example interacting with space and with humankind.

“Architecture uncomfortably exists between the past, present, and future. Architecture creates lines that extend beyond the building. So it is with dance. There is a void here charged with movement.”

One of the sources of inspiration for Ben-Shaul was the book by Ivgeniia Gubkina and Alex Bykov “Soviet Modernism. Brutalism. Post-Modernism. Buildings.”

Another participant at this location is the writer Oksana Zabuzhko. Her participation in the residency is dedicated to working with archives. She was on good terms with Yurii Sheveliov and even published her correspondence with him.

Meanwhile, some residents have already been to the apartment in the Slovo Building. Work and life at Slovo became especially important for writer Liubov Yakymchuk who studies the life and work of Mykhailo Semenko. During her residency, she lived opposite the apartment he once lived in. Yakymchuk is also a co-author of the screenplay (together with Taras Tomenko) for the documentary and feature film ‘Slovo Building’.

Another resident, Yaryna Tsymbal, is probably the most publicly active researcher of literature and literary life in the 1920s and 1930s. Both Valerian Polishchuk and Maik Yohansen about whom Tsymbal published so many articles and also arranged the reprint of their books, lived in Slovo Building. Both researchers also worked in Kharkiv archives and libraries.

There were also children’s writers at this location: Sashko Dermanskyi, Dara Kornii, and Ivan Andrusiak who first performed in Kharkiv in the 1990s. He was then a member of the literary group ‘New Degeneration’. Back then the phenomena, events, and places of the Executed Renaissance were just beginning to be actively revealed. Andrusiak tells about writing the sequel to the ‘Guinea Pig Detective’ here:

“On the first day I didn’t write. I finished some other affairs. The next morning, in the kitchen, I saw that a bird left me a feather on the windowsill. It was like a sign: ‘Ivan, write!’.”

The Literary Museum organised a tour for young readers to visit Ivan Andrusyak of Slovo. Meetings with children are held in the courtyard of the LitMuseum.

Yuri Gurzhi, a musician from Berlin, is set to arrive here in October: together with Serhii Zhadan, they will come up with a music and literature project based on texts by Ukrainian avant-garde artists.

There were also various kvartyrnyky: the rapper Kurgan performance, the lecture of the literary critic Tamara Gundorova, and the readings of the poet Kateryna Kalytko. The first event was the presentation of the ‘Permanent Residence’ book by Serhii Zhadan and artist Pavlo Makov. Tetiana Pylypchuk says that such a coalescence of the arts at the opening did not happen by chance:

“Two iconic Kharkiv artists being in Slovo where not only writers but also painters lived — it was very symbolic.”

Activists and the majority of the population often have different views on public and private spaces. Tetiana Pylypchuk shares the ambiguous attitude of neighbours to the residents of Slovo and Salamandra, to the ‘art bonfires’ emerging at their homes:

“In Slovo the inhabitants of the ‘distant’ house entrances are more friendly than the immediate neighbours. In general, the idea of reviving the history of the house fascinates some people, but everyone is waiting to see how we behave and how well we fit into the format of a residential building. Sheveliov’s neighbours, it seems, have not ‘read’ us yet because we are so quiet. All in all, Sheveliov’s apartment provides a more academic meeting mode, and Slovo — a more ‘hooligan’ one.”

Residents of Petro Lisovyi’s apartment leave gifts and various inscriptions on pieces of paper to their successors. There are also gifts for the residency: for instance, Yaryna Tsymbal presented a portrait of Maik Yohansen. There is a small library (to be expanded) and various visual works. On one of the vases, there are moving words: ‘A flower called Svitlana. Water on Saturdays’.

Thanks to activity and successful communication, two seemingly forgotten and abandoned Kharkiv apartments organically merged into the lively cultural life of the modern city. Today they not only preserve but also popularise and create a new cultural heritage of Kharkiv.

supported by

House of Europe is an EU-funded programme fostering professional and creative exchange between Ukrainians and their colleagues in EU countries. Implementation of House of Europe Programme is led by Goethe-Institut Ukraine with The British Council Ukraine, Institut français d’Ukraine and Czech Centres as Consortium Partners