Kharkiv architecture is experimental by its nature, and imbued with symbols. Red bricks and two-storey houses of the 19th century, constructivist memorial sites, co-operative buildings (the name of a prestigious co-housing project of the Soviet era), and first cultural hubs for the workers of the 20th century. Modern Kharkiv unites all of these symbols and new approaches to the city development. Under the auspices of Kharkiv School of Architecture, students learn to create new objects based on the world experience and the architectural heritage the city possesses.

Throughout its history, Kharkiv played a significant role in commercial, industrial, educational, and literary life of the country. Endless variety of styles and signs of different historical periods co-exist here. Active city development started as far back as Kozaks’ times, in the 17th century. Since then, Kharkiv played a role as the centre for different administrative units — Sloboda Ukraine Governorate, Kharkiv vice-government, Kharkiv province — which gave a boost to the city’s fast development and growth. In the 19th century, the city grew so large that the Old and the New quarters had to be differentiated. The city’s historical museum and first banks were founded then as well, and so were the spacious squares, which remain among the city’s symbols even nowadays.

The 1920s and 1930s make the next landmark in the history of Kharkiv architecture. Such important symbols of Kharkiv as the Derzhprom complex (the House of State Industry) — the embodiment of constructivism, — the area of Kharkiv Tractor Plant (KTP), co-operative buildings, the most famous of which was the Slovo (“Word”), were constructed at the same time.

Constructivism

A style that appeared in the 1920s-1930s in architecture, art, literature, etc. Constructivist architecture can be recognized by sharpness and conciseness of forms, rigidity and functionalism.All historical layers co-exist in the city now: some become transformed based on the modern architecture, and the others preserve the old town atmosphere.

The Old Town. Moskalivka

One of the oldest districts of the city is Moskalivka. Retired soldiers of the Russian Empire — moskali — inhabited this area since the middle of the 19th century. Sometimes this district was called Arabia: its numerous sand mounds made multi-storey housing impossible to build. Therefore, most of the houses here have only one or two floors.

Some streets of this district preserve their original old paving stones and a number of buildings retained the famous Kharkiv red brick made out of the local clay. Many representatives of the country’s cultural elite resided in Moskalivka. Here a building still exists where Claudia Shulzhenko, a Ukrainian singer, spent her childhood; there’s also the family house of the famous artist, Vasyl Krychevskyi.

An architect and the first pro-rector of Kharkiv School of Architecture — Oleksandra Naryzhna — was born in Moskalivka. Four generations of her family lived there.

“My great-granny and Claudia Shulzhenko were close friends, they shared some concert shows, and hung out every day. They both had the same first and patronymic names — Claudia Ivanivna. My granny would play the grand piano, and Claudia Shulzhenko would sing. They were quite close friends and were spending a lot of time together.”

It was in Moskalivka where one of the first libraries in the city was established; and it is now a subsidiary of the main city library named after Ivan Franko. A locksmith’s shop was set up in this district in 1891, and later it eventually grew into the plant Svitlo Shakhtaria (The Mineworker’s Light). The bridges across Lopan river were built at that time, to connect the residential areas and the railway by which the workers commuted to the plant. Mainly elderly people and families that were living here for generations inhabit Moskalivka now, such as Oleksandra Naryzhna’s family. The architect is explaining the main principle behind the district’s development.

“Moskalivka preserves the structure of blocks of six hundred square metres. Its unique feature is that all the houses overlook the street. It’s like a Ukrainian format for townhouses, where each house’s grand entrance is facing the street. During the Soviet era, however, all those entrances were shut.”

A Townhouse

A complex of multi-storey houses that adjoin by sidewalls and share the roof, yet have separate entrances and inner gardens.Each of the new owners renovate old buildings according to their liking, plastering and painting over the old brickwork, changing the facades, etc. The district’s appearance is gradually changing, and not much of the old beauty is preserved, Oleksandra explains.

Architectural heritage of the 20th century. Preservation, comprehension, and restoration

Interaction between different construction epochs is especially noticeable in the outskirts of the city. The Metalist Palace of Culture is one of those important architectural objects that require restoration, but remain in derelict state because of the lack of funding. This building is evidence that Kharkiv’s industrial capacities, its modern appearance and cultural infrastructure, were shaped before the time of the Soviet Union.

The Club of the metalworkers’ trade union, which became the first workers’ club in the Russian Empire, was built in the 1900s by the architect Iliodor Zagoskin. It was built with the funds provided by the plants workers; primarily, the locomotive construction plant, now called Malyshev Plant.

In 1905, the revolution of workers was ongoing in Kharkiv: the plant workers were campaigning for eight-hour working days instead of the twelve-hour shifts. A few years later, the workers began to open activity clubs and to construct facilities for spending their leisure time together. Therefore the Metalworkers Club (now Palace of Culture “Metalist”) was designed with numerous rooms for activity clubs, a theatre, and a library.

A Kharkiv architect Oleksii Beketov reconstructed the building in 1923. The original red brickwork was plastered then, and the building’s exterior changed entirely, while its function remained the same.

According to Ievgeniia Gubkina, an architect and an architectural historian, the chase of progress quite often endangers heritage sites nowadays. These sites require restoration and reinterpretation, which all take time. The Palace of Culture “Metalist” sets an example of the existing problems with restoration in Kharkiv and in Ukraine in general. There is a lack of expertise in this area, and according to Ievgeniia, this may cause loss of authenticity for those buildings — as the time passes, they become impossible to restore.

“When restoration work is done unprofessionally, when people rip off all of the decorations, take away old plasterwork, remove old windows, and so on — this makes it impossible to restore the buildings back to their original state. The restoration should follow the reversibility principle. To me, this is like providing medical care, when you should not cause any harm to the patient. The restorer’s actions should not involve anything irreversible. So, as you are undertaking a restoration, you must keep in mind that the next generation may be more advanced in terms of technology or culture. It is important that they are not deprived of the possibility to do their own proper restoration by your actions.”

At the same time, according to Ievgeniia Gubkina, the city does not become more comfortable when the new architectural objects are built. Green areas vanish, the space between buildings shrinks, and the quality of urban planning deteriorates. Some architects are leaving their profession, in particular, because of the state regulations:

“The legal system demands that the architect is to fully serve the customer, and that is it. Therefore, all we witness is this kind of architecture; the cityscapes of Ukraine, especially of the large cities, all come from customers’ imaginations. They are all built upon such simplistic elements as the contract, the legal system, the norms and rules, and standardisation. All this has nothing to do with the architect. The architect’s role in this process is close to none.”

At the same time Kharkiv has the architectural history, which may become the foundation for its further development. This is, for example, its industrial heritage, which is now marginalised, such as experimental residential complexes of Kharkiv Tractor Plant (KTP). The plant itself was built by the design of Albert Kahn’s firm — the Chief Architect of Detroit, USA.

“The four quarters of very interesting experimental housing make the KTP residential complex; no kitchens, nothing of the kind was envisaged there, because in communism everyone was supposed to be free and dine in the plant’s canteen. The place also had quite a few kindergartens in the design, and they were intended to be connected by the passages, so that everything would make a unified structure. All of this was supposed to deliver the message that everything — the society as well as the architecture — is horizontally connected.”

British architects were inspired by the KTP example, and as early as the 1960s–70s, similar features appeared in the architectural style of British brutalism. All buildings had to become connected and that would make a big residential complex a unified structure, one “organism.” An interesting fact is that Soviet authorities objected to this principle of connecting buildings, and so all the KTP’s passages were eventually cut off.

Brutalism

A movement in design and architecture that uses simple geometrical forms of bare concrete.

Several years earlier, in 1928, a development project of the House of State Industry, the Derzhprom, was built in Kharkiv. It was also known for its passages from one part of the building to the other. The thirteen-storey building became the first Soviet skyscraper of the time.

“The Derzhprom is Mecca for all those who study modern architecture. I saw two people who were hugging the Derzhprom, and one who was kissing it. It is a truly magnificent building. It is modern and innovative.”

Ievgeniia Gubkina explains her view of the definition of the architecture as follows:

“First of all, it is a relationship, a material form of relationships. That is, we have different forms of relationships and different forms of processes in society. Architecture is the cover for all of it. It is an outer layer, a manifestation of what already exists in society. If the society has children, we cannot fail to find a way for these children to spend their time while parents are working. Architecture is a representation of different sociopolitical epochs, it is who we are, it is us.”

In Kharkiv, according to Ievgeniia, different epochs had a plethora of different architectural schools and groups. The principle of knowledge sharing,

which made the ground for such schools, is worth preserving and augmenting.

“This generation’s topic is very important to me, because the sustainability of information and its passage from one generation to another is something very important. Architectural schools cease to exist in our country. I think it is rather an interesting phenomenon that the old architectural schools, or rather their ruins, made the foundation for building a private architectural school [such as Kharkiv Architectural School].”

slideshow

New architecture of Kharkiv

Preserving the bond between generations and creating modern development that brings cultural value — this is the principle of work of Oleg Drozdov, an architect, and a co-founder of Kharkiv School of Architecture (hereinafter the KSA). In 1997, he founded the Drozdov & Partners bureau, whose mission was to establish the link between architecture and the city environment with nature. The bureau’s location has an interesting heritage: it is situated in the house of a famous Kharkiv architect Victor Velychko on Darwin street. The houses in the neighbourhood also have an unusual history: down the street there is a family house of the local gentry Alchevskyi-Beketovs — known philanthropists and cultural figures, and up the street there are houses where a local artist and an architect used to live.

The bureau already designed quite a few buildings in Kharkiv. Among them are two shopping centres — the Ave Plaza and the Platinum Plaza. The Heirloom development stands out from all of the bureau’s projects. This is a residential building with offices, situated in Chernyshevska street. It consists of a brick volume and retracted superstructure. Its main construction material is classic Kharkiv red brick, which was recovered from a demolished building on a neighbouring street. The name — “Heirloom” — is in tune with the approach that underlies this project: a combination of old and modern, the past generations’ heritage embodied in the modern architecture.

The inheritance principle was applied to another well-known project of the Drozdov & Partners bureau — Kyiv Theatre on Podol. Finding Old Kyiv bricks took a long time, but a sufficient quantity was found at last.

Ukrainian projects are not the only initiatives in the bureau’s portfolio. The bureau works with European countries such as Switzerland, the Czech Republic, Austria, and Spain. Another local project is the Literature Museum reconstruction — an important case for Kharkiv — and it is scheduled for the near future.

Oleg Drozdov explains what architecture means to him,

“Architecture is, first of all, a conversation with time: with the past and the future. The conversation about people’s feelings, memories, and dreams; about different cultures and history. It makes teamwork, teamplay possible. It is a profession and a hobby at the same time because you are always an architect: when you are falling asleep, when you are on vacation, always.”

In Oleg’s opinion, what architecture does is more important than how it does it. This sphere reacts to social changes, to the overall situation. Yet the general level of culture is important for the development of the architecture, as is the attitude towards the traditions in society, and its vision of the future.

“The evolution of architecture is not always directly linked to people’s welfare. With all the money we already have [in the country] we could create a rather decent architectural culture and live in different surroundings. I think this demand for good-quality architecture is growing, however slowly.”

slideshow

One more condition is important for such progression — co-existence and mutual respect of historical and modern developments:

“Kharkiv is very illustrative in this sense. A lot of architectural objects dating back to the 1920s–1930s stand here next to the monuments of Ukrainian modernist architecture of the early 20th century. They all amalgamated into one visual mass, with their histories blended, creating a holistic city environment.”

The 1920s were a time of artistry, creativity, work, and scientific unions, Oleg Drozdov explains.

“There are the House of Scientists, the House of Medical Workers, and so on, in Kharkiv. The idea of such clusters was very popular in the 1920s. People in these ‘campuses’ were concentrating on their professional matters all day round: in the morning, at dinner, or while doing their laundry. The beginning of the 20th century was not the time of singled-out talents, but the time of manifests and informal creative groups. The entire Soviet avant-garde consisted of such self-formed organisations and groups.”

Oleg Drozdov believes that the famous Slovo building represents the most significant example of cooperative living between creative people. This cooperative housing was built at the expense of Ukrainian artists and writers, most of whom ended up victims of the Soviet repressions of the 1930s. The building accumulated all sorts of creative energy and was a think tank for the Ukrainian creative intellectuals of the time.

“All these people, seemingly so different, but united by their common interests, would pay each other visits, dine and wine together, and hold discussions. Before the infamous 1930s, the place’s doors were never locked, the social gatherings would never end, being fuelled by the building itself and its space.”

Litterateurs, the actors of Berezil Theatre (the innovative theatre of the early 1920s), creative professionals in the fields of architecture, design, and art inhabited the Slovo.

“I think that this super successful social cooperation, this communication, generated a variety of new literature, new theatre, new art. The knowledge, the ideas, and the experiences were exchanged so intensively, because all of these creative people lived next to one another.”

Kharkiv School of Architecture

At the Kharkiv School of Architecture (KSA), they strive to restore the broken link between the generations and to create a new architectural culture for Kharkiv and Ukraine as a whole. It is a private educational establishment founded in 2017. The idea of the establishment formed long before that — between 2008 and 2014. Oleg Drozdov explains that this was his response to the realities of the time, and a much needed initiative by the architectural community:

“Kharkiv School of Architecture is an egoistic project in a way, because you can only become a true professional when you have a competitive environment. When there is no such an environment, it needs to be created.”

Kharkiv School of Architecture is situated in Kontorska street, near the old city centre. The building where the school functions used to be owned by a Kharkiv merchant. One of his aspirations was to create a space for hosting his guests and for organising cultural events. According to Oleg Drozdov, the co-founder, his school carries on the tradition:

“The succession of the events that take place here goes back to 1886. We, among others, make some of our premises open for public events. For example, we host various shows too.”

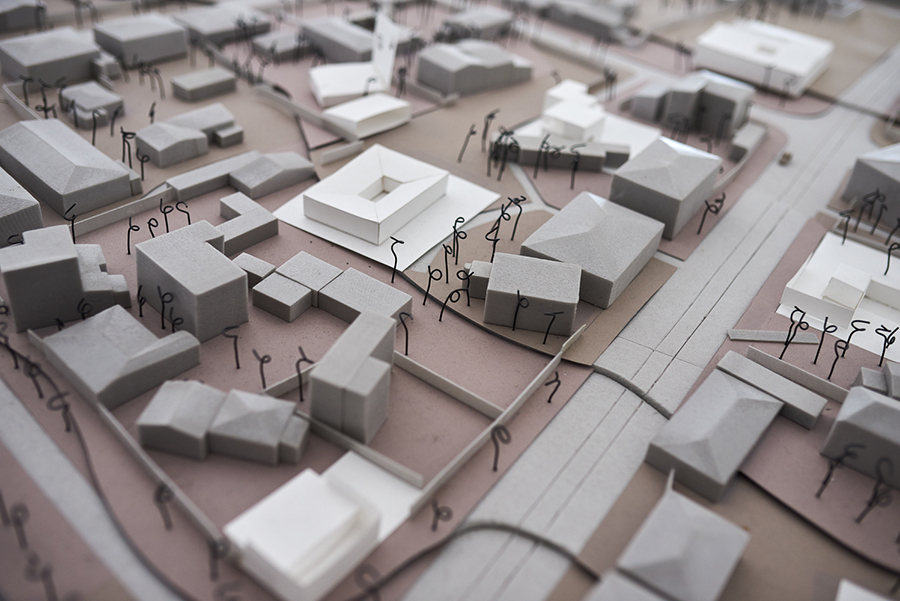

In addition to common areas, there is a studio, where students spend most of their time, workshops with tools for creating scale models, a computer class, and a public library, which is open to everyone interested. Creating the best contemporary architectural library in Ukraine is one of the team’s missions.

slideshow

The curriculum is composed based on the principle of combining the best global experience and the challenges that exist in Ukraine. The KSA team

aspires to cultivate this architectural way of thinking and practical skills. Starting from the first year, the students receive real cases to work on and make things with their own hands. For example, most of the furniture on the school’s premises are the students’ works. Oleg Drozdov also talks about their collaboration with the real customers as well:

“This [project] is a redesign of a typical Soviet-era school building to adapt it to the new pedagogical models. And we chose three schools: one in Kharkiv and two in Kyiv. We researched how these new methods, new concepts, can change the existing schools, and how architecture can work with it. This was a remarkable experience, because the students grasped the idea of this new pedagogical concept, and by using the space accordingly, they were trying their best to supplement it with everything it needed.”

The KSA has bachelor’s and master’s programs as well as “The Zero Year” course of study. The latter was developed to give the students an insight into the profession of an architect, to provide them with basic theoretical and practical skills, and to help them to define the direction of further personal development. After completing the bachelor’s degree, the students are ready to work as architects. The master’s program, in contrast, prepares a specialist who can run a business and use appropriate business communication. Oleksandra Naryzhna, the School’s first vice-principal, is confident that the KSA graduates can become more than good architects:

“Our master’s program aims at preparing the new generation of young leaders of the office, capable of playing the business game at a professional level.”

Also, the KSA students should develop not only project creation skills. A good architect understands the city space and its connection to the social environment, they have an intuitive feeling for the materials which can be worked with.

The entire work of the KSA is organised around the students themselves, their personalities, and their levels of knowledge. It also accounts for contemporary trends. This is what makes the education received at the KSA School different from classic academic education, Oleksandra Naryzhna believes:

“As we can see over the past 20–30 years, the public education program has not transformed significantly. And when we ourselves started developing the School’s curriculum and its ideas, we were looking at the challenges we are facing today in other countries, such as Great Britain, the USA, Sweden, and Switzerland, which have the most advanced curriculums, and they re-evaluate the architects’ qualifications every year: i.e. what the architects should know, or how they should work.”

Nowadays, Kharkiv School of Architecture has a branch in Kyiv; however, no further expansion is planned. Oleksandra Naryzhna says it is very difficult, especially in terms of finding professor-practitioners:

“We cannot count on other cities in Ukraine, unfortunately. We have a community we formed in Kharkiv, so some of those people travel from Kharkiv to Kyiv to teach, but not all 15 of them, of course. There are also teachers who travel from Kyiv to Kharkiv. And I would say that these are the two cities that allow us to fill the pool of teachers within our community.”

According to Oleksandra, the KSA has foreign partners (educational establishments, architecture bureaus, etc.) and they also co-operates with the professional community of the architects in Ukraine, which yearns for talented students, students who will be ready to bring new ideas into life and to give new meaning to the heritage. Kharkiv is especially likely to yearn for such architects, so that the city can impress not only with its historical buildings but by its modern developments as well.

According to Oleg Drozdov, the main objective of the Kharkiv School of Architecture is to transform Ukrainian cities.

“KSA students become immersed into the global professional discourse, but at the same time the school curriculum forces them into the Ukrainian reality, so they are ready for it. They work all the time. And so, they should not ‘stutter’ as they ‘communicate’ [through their work] with society and with the world they enter after our school.”

Oleksandra Naryzhna stresses that Kharkiv is a city of ambitious people and projects. And it should remain this way:

“Ambitious projects change Kharkiv, when instead of changing a little bit of this or that, we re-imagine the city in a new way. Such big radical projects can change the perception of the city very quickly.”

Kharkiv is often referred to as a city of students. Around 35% of the foreign students who are receiving higher education in Ukraine are studying here, as does a large part of Ukrainian students. Oleksandra Naryzhna calls the city some kind of a transit point for the young who come to Kharkiv, study here and then move on. One of the tasks for the city’s current urban planning strategy is to turn the city from a transit point to a settlement point, which will accumulate the energy of changes, the architect believes.

“I hope that life in Kharkiv will stimulate people to stay. I think it is the most important mission for Kharkiv: to keep people, ideas and talents here. The ambitious people who have the capacity and the energy for bringing the big projects into life should be staying here. So that this energy is not dissipated.”