The Korean community in Ukraine began to burgeon at the beginning of the 20th century. Tens of thousands of ethnic Koreans endured many ordeals before finding a home in Ukraine. In the early 1900s they were first forcefully resettled to the Sakhalin island by Japanese authorities and then again in 1937 they were deported to Central Asia, this time by the Soviet Union. Mass resettlement of ethnic Koreans to the territory of Ukraine began in the 1960s, when they moved to southern Ukraine to rent fertile lands in the region for farming. Since then, many Koreans have also moved to the big Ukrainian cities in order to obtain a higher education.

Numbers vary amongst the various data sources, but between 20 to over 40 thousand Koreans inhabit Ukraine today; mostly living in the south of the country. Despite the considerable assimilation – a product of the Soviet policy towards the national minorities – today the Koreans of Ukraine are doing their best to revive their language and culture.

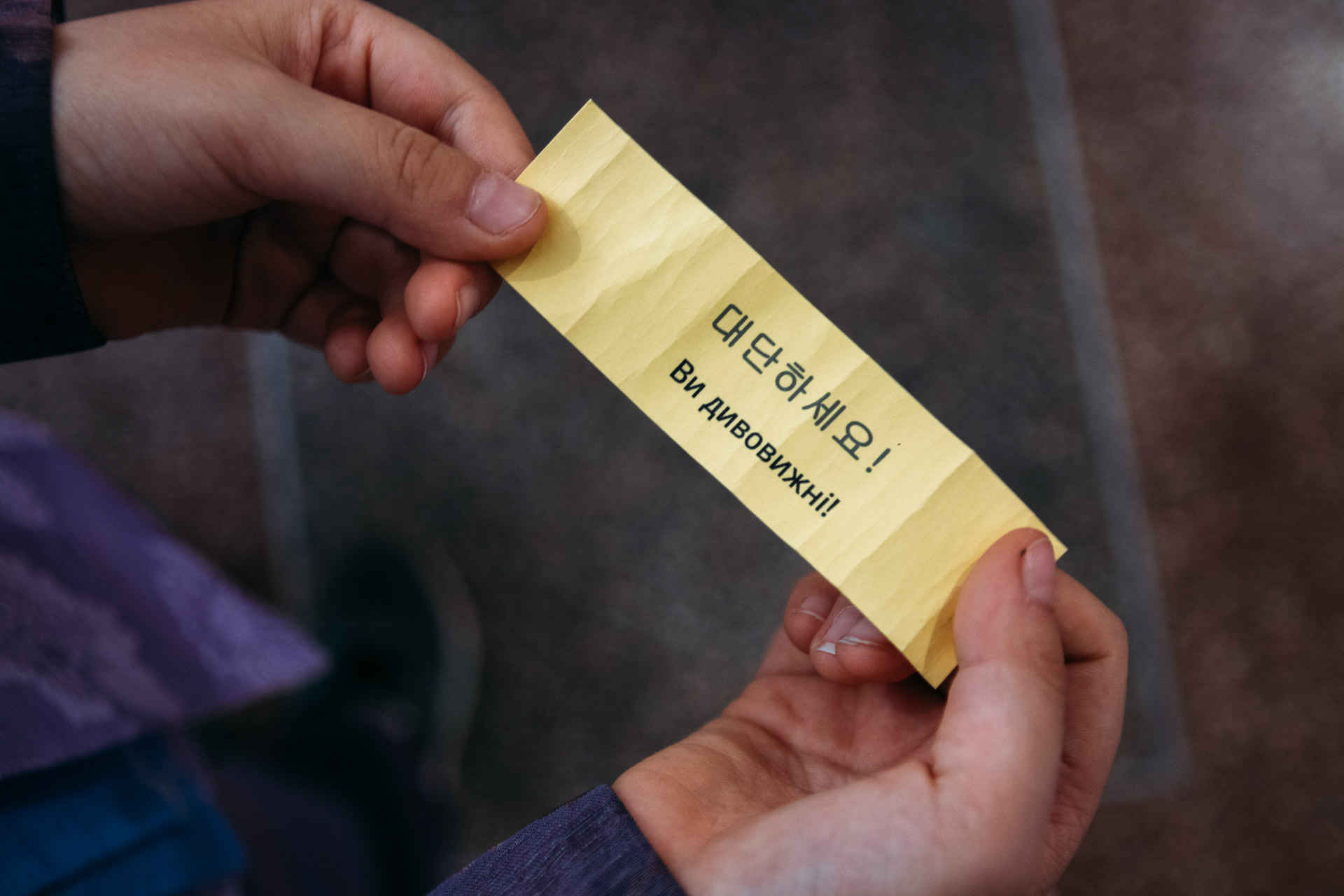

«Koreada» is a unique roving festival celebrating Korean culture in Ukraine. For over 20 years, it has been taking place every autumn in different regions of Ukraine. Usually, the festivities are carried out in big cities, but this year it was decided to pick a small town to host the event. Apostolove, a town near Kryvyi Rih, has the highest concentration of Korean residents in the Podniprovia and Zaporizhzhia regions.

Marina Li. Dance

At the first festival in 1995 in Kyiv, among the performers were dance companies from countries such as Korea, the USA, and Uzbekistan. At that time, the dancer Marina Li had seen Korean traditional dances and together with colleagues decided to establish a Korean traditional dance company “Toradi”. They had to start everything from scratch, Marina recalls:

— At the beginning we didn’t have a place for rehearsals or even the necessary basic knowledge for how to dance at all. Our first dances we’d learn from videotapes or some materials found by chance. Later, the Korean embassy in Kyiv arranged a volunteer to come and teach us the basics of Korean traditional dance.

Since then the “Toradi” ensemble has performed at the festival every year. Marina tells, that though the ensemble’s lineup has changed several times, eventually the participants come together to continue researching dance:

— We do grow older, but despite this, we keep preserving our dances. We just really want to keep developing our ensemble.

Marina Li was born in Ukraine. Her grandparents were forcefully deported from Central Asia, however, this term is not in use anymore. to Kazakhstan in 1936–37. Later, Marina’s father came to Ukraine to study, and this is when he met her mother.

They do not speak Korean everyday within the family. Her father has already forgotten Korean, and Marina says her Korean is not good enough. Though Marina’s Ukrainian is fluent.

Besides leading the ensemble, Marina Li works at the theater “Dyvnyi zamok” (“Strange castle”) and teaches theater art at a private school.

These days, “Toradi” dances the widest variety of traditional Korean dances out of all the Korean dance ensembles in Ukraine. Amongst others in their repertoire, the ensemble has a range of dances performed to the beats of traditional Korean drums. These dances date back to ancient shaman rituals, where every movement along with the sound of the drums were full of meaning. With time, the drums became vital in Buddhist and Confucian temples, says Marina:

— The sound of these drums is believed to heal. For instance, when someone was ill, they would be placed in the middle of a circle of drums. The rhythms of the drums would lift the person’s life energy and help with recovery.

Central Asia

A geographic region that includes the countries Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, and Kyrgyzstan. During the Soviet times, this territory was known as the “Far East”.

The dancers in “Toradi” have even travelled to South Korea to learn new dances such as the Janggu Chum (장구춤), a dance with sandglass-shaped drums and the Chaesang Sogochum (채상 소고춤), which is another drum dance. Performers try to enrich their repertoire with new dances that mix traditional and modern styles together. For example, dances where the dancers use lanterns are actually not considered traditional, but rather are modern dances inspired by traditional movements and accompanied by traditional music.

Costumes for “Toradi” performances are either handmade by the dancers themselves or brought from abroad.

“Hanbok” is the general term for traditional Korean clothing. Women’s attire consists of a skirt (“chima”) and a short long-sleeved blouse (“jeogori”). All the costumes are variations of this set. For example, there is a dance that emphasizes the sleeves and so the ensemble wears a more sumptuous costume, which also symbolizes the beauty and grandeur of the royal court. For the shaman dance with knives, a hat and a string of beads are necessary additions. And for the dance with sandglass-shaped drums, the dancer wraps a piece of fabric around his or her waist so all the movements and jumps go smoothly.

Though Marina runs the ensemble on a voluntary basis, for her it is a big passion as she cherishes the traditions of her family and her people:

— Everyone must keep their own roots. And art is something from deep within oneself. From history. If we keep it, if we show it to other people, we do not let ourselves forget our roots.

The community keeps the culture not only through dance, but also through traditional holidays celebrated together within the family. Marina says that in every Korean family the first birthday of a child is especially celebrated, as it is believed that on this day a child chooses his or her destiny. The 60th birthday is also considered a special birthday and is festively celebrated since it is believed that a person passes five life cycles before their 60th year. Marina Li’s family gathers every year to celebrate Lunar New Year according to Korean traditions. Then they cook traditional Korean dishes.

Koreans in Ukraine

As a result of 1904-1905 Russo — Japanese war, Japan occupied the southern part of Sakhalin island. The Japanese Empire actively pursued a colonization policy at that time and by 1910 Korea had completely fallen under its rule.

Soon, during the civil war in Russia, the northern (Russian) part of Sakhalin island was also occupied by Japan. Japan actively started resettling Koreans from the North of the country to the island to build airports, mines, etc.

Everything changed during World War II when the Soviet authorities issued a decree “On the expulsion of the Korean population from the border areas of the Far East (Southern Asia — ed.) region”.

172 thousand ethnic Koreans were forcefully resettled to the desert and other uninhabited areas of Kazakhstan and Central Asia. One of the reasons for this was their alleged espionage and collaboration with Japan, despite the fact that Koreans suffered under Japanese occupation.

slideshow

After Japan was defeated in World War II in 1945, Sakhalin island was transferred to the USSR. At the same time, Korea was divided between the two countries that fought against Japan: the northern part was taken by the Soviet Union, while the southern was taken by the USA. However, deported Koreans had never made it back home. It was impossible.

Koreans have always been farmers, so in Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan they also cultivated the land. In other words, they worked hard to change virgin lands into collective farms.

slideshow

According to the 1983 census data, the biggest Korean community lived in Uzbekistan. Here the act of forceful resettlement was never adopted, which meant that such people had no right to education or work. This led part of the Koreans population there to emigrate to other Soviet republics, most commonly to Russia and Kazakhstan. In 1967 the Koreans began resettling to Ukraine. They came as seasonal agricultural workers, for example to plant onions and watermelons, and mostly in the southern regions, such as Kherson, Mykolaiv, Dnipropetrovsk, and sometimes to Crimea and Odesa.

Kan Den Sik. Language and community

After Khrushchev’s Thaw, it became possible to freely move between the Soviet republics and Kan Den Sik, an aspiring student then, arrived in Ukraine to apply to the Kyiv Polytechnic Institute. After graduation, he decided to stay in Ukraine and is currently the president of the Association of the Koreans of Ukraine and the head of the Korean Cultural Center.

In 1995, Kan Den Sik organized the Korean division at the Kyiv National Linguistic University. The division continued to develop and in 2017 it even became its own separate department of Korean philology.

In 2010, Den Sik founded the Korean Cultural Center was and became its president:

— I just had to do it (start a cultural center — ed.). Someone just had to start.

Kan Den Sik says that for a long time he didn’t speak any Korean at all. He used Japanese language more. But once Ukraine and South Korea established diplomatic relations in 1992, Korean speakers were in high demand and his Korean skills became of use:

— I speak fluent Korean and I know Korean culture very well, because I am second-generation Korean. My parents were Koreans, who moved to Sakhalin island at the time of Japanese rule in Korea. They spoke only Korean, while I finished secondary school (in Russian — ed.).

Today Korean is a very popular and high demand language around the world: it is one of the top-10 most spoken languages worldwide. This is due to the economic boom in South Korea and popularity of modern Korean culture, which includes famous dramas and tv series of Korean cinema, K-pop music, etc. Import revenue of Korean cultural products today is bigger than the profits of globally known Samsung.

Even so, there are still few people in Ukraine who speak Korean well. They are not many even amongst Kan Den Sik’s colleagues. He explains that here mostly live fourth and fifth generation Koreans, descendants of those who resettled from Sakhalin island and former Soviet republics. Neither Japan nor the Soviet Union supported Korean language and culture, so Ukrainian Koreans almost do not speak it. They mostly speak Russian, sometimes Ukrainian:

— This (learning Korean — ed.) is a problem. This is the biggest problem we are trying to solve. This is the most important task right now.

However, today there are Korean language schools in Kyiv, Kharkiv, Dnipro, Odesa, and other cities of Ukraine.

For instance, in Kharkiv there is specialized “Dyonsuri” secondary school that teaches Korean. On a professional level one can learn Korean at the Kyiv Linguistics University, where Kan Den Sik teaches, and also at Kyiv National Taras Shevchenko University. In Odesa, South Ukrainian National Pedagogical University named after Kostiantyn Dmytrovych Ushynsky and in Dnipro, University of Customs and Finance offer Korean as an elective course.

Nevertheless, says Den Sik, this is not enough to ensure quality language training. We are short of facilitators, teachers who know the language and teaching methods at a professional level. Currently inviting teachers from Korea is hard since there their salaries are several times bigger than here.

The Korean community is supported mostly by the Embassy of the Republic of Korea. Generally, the Association almost entirely works on a voluntary basis:

— Our Association is a member of the Council of the National Communities of Ukraine. For many years we’ve been asking authorities to at least give us a facility, something like a House of Nationalities. Unfortunately the issue is still not solved and we do not have a place where different communities could gather. We do still gather, but every time we have to worry about simple things like the venue. Among other things, they also publish a newspaper.

— Ukraine is my second motherland. I have been living here for many years, most of my life. My wife is Ukrainian, and so accordingly is my family. In principle, Ukraine has given me everything: I have grown here as a person, received a PhD, and became a professor. Everything I have, I achieved in Ukraine.

Svitlana and Ernest. Cuisine

Svitlana Khan and Ernest Kim’s family, from Apostolove, is preparing for this year’s “Koreada” in a unique way — in the kitchen. Their job is to cook traditional Korean dishes for all those attending the festival.

Once Svitlana finishes cooking, she shares the recipes of the main dishes.

Korean aubergine salad is called “gaji he”. For this, the aubergines are boiled, sliced, rinsed, and then salt and spices are added. Cucumber salad is called “cucumber choi”. Cucumbers are sliced, salted, soaked in spices, and then fried meat and onions are added. For the “carrot choi” salad, carrot is prepared in the same way as the cucumbers. Sometimes meat is added to it as well. For “kimchi”, the same steps are followed but with Chinese cabbage. Some add carrots and flour.

“Siriaktimuri” is a traditional Korean soup. It contains finely chopped green Chinese cabbage and meat, mostly pork. The essential ingredient is a traditional spice called “tyai”.

slideshow

Svitlana and Ernest were both born in Tashkent (the capital of Uzbekistan — ed.), and lived there for a long time. Svitlana’s parents were also born in Tashkent, while her grandparents were from the Primorsky region, as were Ernest’s parents as well.

For a while, Svitlana and Ernest were traveling back and forth to Korea for work. Later, in the 1980s they began going to Ukraine for work. Ernest’s sister married a Ukrainian man. In 1996, Svitlana and Ernest came to visit her and decided to stay in Ukraine, settling down in Apostolove.

Apart from Korean food, Svitlana also cooks Ukrainian food. The couple admits the tastiest potatoes they have ever tried are in Ukraine:

— Our grandson is Ukrainian. He likes to eat potatoes, pasta, Ukrainian borshch (a traditional soup made of beetroot). His friend’s grandmother even taught me how to make it…

slideshow

Svitlana Khan and Ernest Kim’s three children currently work in South Korea. Svitlana says that one or two people in almost every Ukrainian Korean family, go there as temporary foreign workers. When Svitlana and Ernest visited their children in Korea and tried the modern Korean cuisine they admit that they missed Ukrainian food:

— In Ukraine everything is so tasty, while here (in Korea — ed.) the food just does not taste right. It is very unusual, nothing like what we normally eat. Everything is different.

Even though they are ethnic Koreans, they have lived in Ukraine for over twenty years now. Their neighbours are Ukrainians. Here, in Apostolove, their son and grandson were born:

Before anything else our son is Ukrainian. He unites us. This is his and our motherland. He needs his language. How can I leave my child without his mother tongue? Our grandson has a very mixed national heritage: his great grandmother is pure Turkish, his great grandfather is Ossetian (or Chechen), and so his grandmother is Turkish and Ossetian. And we are Koreans. Just look at his roots! His last name however is Tkachuk (a typical Ukrainian last name).

South Korea is much smaller than Ukraine. And such a small territory is home to 52 million people! And over 8 million Koreans live around the world.

Though Ukrainians need visas to go to Korea, they are quite easy to obtain. Ethnic Koreans can get five-year working visas to Korea. That is why many Ukrainian Koreans, especially the young, go there to work.

The couple from Apostolove does not want to resettle in Korea since they feel at home in Ukraine.

— We have a different mentality. We are used to living here. Unlike in Korea, where everything is unfamiliar, we know everything here.