Krymchaks are an indigenous people of Ukraine that emerged on the Crimean Peninsula alongside Crimean Tatars and Karaites. Their primary distinguishing feature is their faith: they practice Orthodox Judaism with Krymchak prayer rituals. The Krymchak population has always been small. With the beginning of Russia’s temporary occupation of Crimea in 2014, some Krymchaks had no choice but to leave the peninsula for mainland Ukraine, where they continue to preserve their traditions and tell the world about themselves.

This story was written before Russia’s full-scale invasion.

Every day, Viacheslav Lombroso puts a cezve (Turkish coffee pot — ed.) on the stove and waits for it to heat up and the moisture to evaporate. He pours in coffee beans and stirs continuously. He waits until there is a light aroma of roasted coffee and then adds sugar. Next, he adds water to the mixture and, still stirring, waits for the coffee to start rising. Viacheslav deftly pours the full-bodied, hot drink into cups and starts his day in Lviv with thoughts ofSimferopol, because “a Krymchak always remembers that Crimea is their home.”

One of Viacheslav’s most cherished memories of his native home is coffee made according to his grandfather’s recipe.

“My grandfather enjoyed making coffee. I used to call him Yusuf-can. ‘Can,’ pronounced ‘dzhan,’ means ‘soul.’ My soul. Yusuf comes from his name Joseph. We had such a warm connection. I miss him dearly. Every time I visited him, he would ask: ‘Would you like some coffee?’”

How a Krymchak family moved from occupied Crimea to Lviv

Viacheslav is from the city of Simferopol (“Aqmescit” in Crimean Tatar language). He used to live with his parents and brother on the first floor of a house, and his grandparents lived on the third floor. His grandfather told the grandchildren a lot about Krymchaks, taught them customs, and shared Krymchak parables known as ‘mayses.’ Viacheslav’s grandparents were among the few local Krymchaks who managed to survive the Holocaust.

“My grandfather lived in Bilohirsk (formerly called Qarasuvbazar) before World War II. During the German occupation, he, his two sisters, and their mother narrowly escaped across the front line to Krasnodar Krai, and then to the Caucasus. During the war, my grandmother lived in Chechnya, in Grozny. And they only returned to Simferopol in 1962.”

Before Russia’s invasion of Crimea in 2014, Viacheslav owned a private law firm in Simferopol. His office was located in the Qrımçahlar Krymchak Cultural and Educational Society building. For a time, he was a board member of this society. His clients would come from various Ukrainian cities, so Viacheslav sometimes visited court hearings in Lviv or Kyiv. When the Euromaidan protests against the Yanukovych regime were spreading across the country in 2013—2014, he was engaged in a court case in Lviv. Viacheslav’s client ended up becoming a friend.

“In the evening, we would go to Euromaidan, and in the afternoon I would go to court.”

In the spring of 2014, when Viacheslav and his brother were on duty near military units in Simferopol, they tried to fend off attacks by men who arrived in cars with Russian license plates. At that time, they had no idea that these assaults would be the beginning of Russia’s seizure of Crimea.

While this was taking place on the peninsula, Viacheslav’s client from Lviv invited him and his family to leave Crimea and stay at his home in Lviv.

“When I was leaving the peninsula, I saw that a train with tanks was going towards Crimea. And I have a family there, I have children there. At that moment, I made the decision that I would be leaving.”

Those events determined what the Crimean lawyer would do in the future. His fellow defenders of the military units in Crimea founded the NGO Crimean Wave. Internally displaced persons (IDPs) from the East of Ukraine and Crimea, having found themselves in a situation just like Viacheslav’s, turned to this NGO for help.

Known to many in Crimea as a professional in economic law, Viacheslav had to build a new career in Lviv, re-establishing contacts and developing a reputation.

“So you had to move to another city, and you need, for instance, to cook borshch. What does one usually need for this? Just to buy the products and cook. But an IDP needs to buy plates, a pan, a ladle, and spoons to cook borshch. Everything from scratch.”

From 2015 to 2017, Viacheslav worked for the NGO CrimeaSOS in addition to Crimean Wave, where he provided legal assistance to IDPs. Since 2018, he has been working for the Lviv City Council in the integrity and prevention of the corruption sector, analyzing corruption risks.

History of the Krymchak people

According to one account, the history of the Krymchaks began with several waves of Jewish migration from Byzantium, the Middle East, and even from southern European countries to Crimea. This is evidenced by the different origins of Crimean names and surnames: Lombroso and Angelo come from the Italian language, Bakshi and Izmirli are Turkish, Gurji is from the Caucasus, and so on. They began to settle on the Crimean Peninsula in the 13th century.

According to other sources, the oldest Krymchak rite prayer book dates back to the 10th century, which indicates that the Krymchak ethnic group existed before the resettlement of Jews to Crimea and probably has Turkic roots.

The first Krymchak centre in Crimea is considered to be Kafa (now known as Feodosia). In the 13th and 14th centuries, it was a colony of the Italian Republic of Genoa. With the Ottoman occupation of the southern territory of Crimea in the 15th century, the Krymchaks headed north and began to settle closer to Crimean Tatars. Qarasuvbazar (now known as Bilohirsk) became a new Krymchak centre.

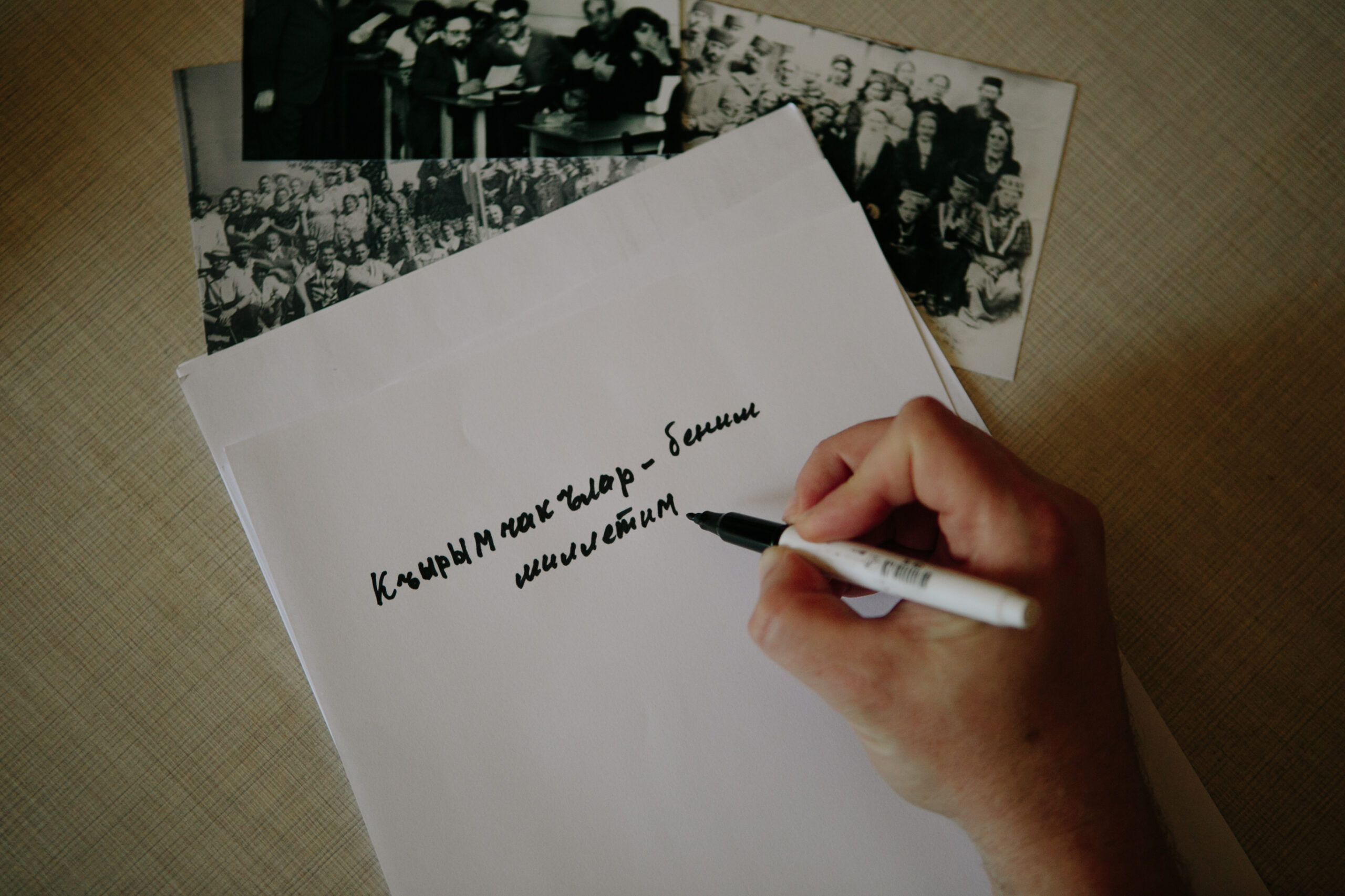

In the media, and later in official documents, the word “Krymchak” (“Qrımçahlar” in the Krymchak language) first appeared in the 19th century. Back then, the Krymchak community was actively developing in Crimea. Krymchaks were mainly engaged in handicraft making, which guaranteed the well-being of their families. However, the 20th century became tragic for Krymchaks and other Crimean peoples.

In the 1920s, Krymchak prayer houses in Crimea, called “kwaals,” were closed down. Due to famine and recurring pogroms, Krymchaks left the peninsula for the land that now belongs to present-day Israel. Later, others left for the United States.

Before World War II, approximately 6,000 Krymchaks lived in Crimea. After the Germans seized the peninsula in the fall of 1941, they executed almost the entire Krymchak population along with the Jews who lived in Crimea at the time. Only a thousand Krymchaks were able to survive the Holocaust on the Crimean Peninsula.

Before the start of Russia’s occupation of Crimea in 2014, Viacheslav Lombroso and other Krymchaks used to travel to the 10th kilometre of the Simferopol—Feodosia highway every year on December 11 to honour the memory of the Krymchaks and Crimean Jews who were victims of the Holocaust. On this Memorial Day, known as “Tkun,” Krymchaks recite the Kaddish, a traditional prayer for the dead.

“During the previous occupation of Crimea (the German occupation during World War II — ed.), many Krymchaks were shot on the 10th kilometre of the Feodosia Highway. There were many execution sites within the peninsula, but most Krymchaks were shot here. After the post-World War II deoccupation of Crimea, Krymchaks found this site themselves. They raised money and erected a memorial there. Then, several decades later, a full monument was built , commemorating all the Jews who were executed there.”

“The Crimean Jews”: the Krymchak faith

Krymchaks are often perceived as “the Crimean Jews” because they practice Orthodox Judaism. However, Krymchak prayer rituals differ from the traditions of other branches of Judaism. They developed separately from neighbouring communities and, at the same time, interacted with them, so that different communities influenced and adopted customs from one another.

Doron Hondo, a Krymchak rabbi from Simferopol, claims the Krymchak Jewish tradition is over 1,000 years old.

The uniqueness of this tradition is that it combines several Jewish practices. The prayer ritual that Krymchaks still adhere to is called “prayer according to the Kafa tradition.” Prayers are read in Hebrew, the language of the Holy Scriptures, except for one of the prayers, the Kaddish.

The Krymchak language and culture

The development of the Krymchak language and culture came to a halt due not only to the extermination of the Krymchak population during the Holocaust, but also due to the 1944 deportation of the Crimean Tatars, as they largely formed the language environment for the Krymchaks. After this forced deportation, people of other nationalities began to settle in Crimea. To communicate with their new neighbours, the Krymchaks had to speak Russian. In addition, in the USSR, passports could indicate any ethnic nationality except for Krymchak. Krymchaks were recorded as Jews or Crimean Tatars. Thus, Viacheslav Lombroso’s grandmother was registered as a Jew after World War II.

“Soviet bureaucracy proceeded from this: ‘we believe that if you were under occupation, then you were destroyed. And if you were destroyed, then Krymchaks no longer exist.’”

The policies of the Soviet Union led to a point where Viacheslav’s generation could no longer speak the Krymchak language, “Chagatai.”

Chagatai belongs to the Kipchak group of Turkic languages. At first, it was written using the old Hebrew alphabet, known as “jonkas,” which can still be seen in ancient Krymchak manuscripts. Starting in the 1920s, Krymchak texts began to be written in Latin script and later in Cyrillic.

The Krymchak language is sometimes considered an ethnolect of the Crimean Tatar language due to just slight differences in their vocabulary and grammar. However, philologist David Rebi, one of the last Chagatai speakers, had a different opinion. He published a textbook of the Krymchak language and Krymchak dictionaries.

In the 1990s, he founded the “Grandfather and Grandson Sunday School” where he taught the Krymchak language to anyone who wanted to learn.

“As a rule, in our generation, in the ’90s, our grandparents still knew the language, but our parents did not, and grandchildren needed to be taught. That is why David Rebi had the idea to make such a school, where children, their parents, and their grandparents would sit together at desks. And he taught there.”

For Krymchaks, it was more than just practicing their language. The key goal was a meeting of generations, where relatives and friends would discuss common topics.

slideshow

Relationships in a Krymchak family have certain rules based on mutual respect, regardless of a family member’s age. There is even a saying in the community that you should give “water to a child and words to an old man.” This means that when allocating resources, the child always has priority, and when making decisions, the eldest member of the family gets the final say.

Viacheslav’s grandfather’s desire to preserve the Krymchak identity and pass it on to future generations came true. Viacheslav, who already has children of his own, continues his mission.

“I am gradually introducing them to our culture so that the word ‘Krymchak’ is meaningful to them. At least they know the word and that they are Krymchaks.”

Culinary traditions of Crimea and the Krymchaks

In 1990, the world’s only book on Krymchak cuisine, including traditional and modern recipes, was commissioned and published at the expense of the Qrımçahlar society. Krymchak cuisine has much in common with the cuisine of Crimean Tatars and Karaites. These peoples amicably argue with each other over whose dishes they really are. Puff pastry has an important place in Krymchak cuisine: it is used to cook the most common dish for family and national holidays, a closed pie known as “kubete.”

slideshow

“You take mutton, cut it into pieces, then dice onions, potatoes, and greens. Then you take puff pastry and make a closed pizza out of it. There should be dough at the bottom and on top. And there are potatoes, onions, vegetables, meat, and greens inside. A hole is made in the centre of the pie. At some point, you need to pour water into this hole so that the filling does not dry out, but boils a bit.”

Krymchaks also use puff pastry to make “choche,” pies with various sweet and savoury fillings. They are also called Karaite pies.

Among their everyday dishes are “kashykh kulakh” and “suzme.” Both are very similar to small dumplings. The first is served with tomato sauce, and for the second one, they prepare a nut sauce called “alede.”

Viacheslav Lombroso has one favourite flavour from the rich Krymchak cuisine.

“I miss the taste of my childhood very much. When you eat mutton, your hands then smell like mutton for half a day.”

Even a thousand kilometers from Crimea, Viacheslav seeks to surround himself and his family with familiar smells and tastes. He says that on the holiday of Kurban Bayram (Crimean Tatar name for Eid al-Adha — tr.), the Crimean Tatars would always share mutton with their Krymchak neighbours. Krymchaks thanked them with unleavened bread, known as “matzah,” for Jewish Passover, or Pesach. Crimean Tatar friends of Viacheslav continue this tradition and bring him fresh meat every year, but now – to his Lviv apartment.

Viacheslav sometimes visits Crimean Tatar restaurants in Lviv to feel at home. There, he can ask them to cook national dishes “like they are made at home.” And he is never turned away.

How Krymchaks tell the world about themselves

Viacheslav Lombroso considers it a primary personal task to tell the world about his people. In his opinion, Krymchaks need a clear strategy to preserve their cultural heritage and maintain constant communication with the public.

“If there is a lack of information, then we all know who will spread their propaganda. Therefore, our task is to ensure that information about key historic events for the Krymchak people, about prominent Krymchak figures, and, in general, about how we work to preserve our cultural heritage comes from the source.”

Viacheslav cooperates with the Foundation for Research and Support of the Indigenous Peoples of Crimea, an international non-governmental organization that protects the rights of the Crimean peoples, in particular the Krymchaks. Every year, the Foundation sends representatives of the indigenous peoples of Crimea to Geneva or New York for various international events. In 2018, Viacheslav also went to Geneva for an internship, where he learned to develop parallel reports on the protection of the rights of indigenous peoples. In addition to one-time trips abroad, he also performs a crucial task at home.

“I collect information from Crimea and try to somehow deliver it here to the state services for ethnopolitics. At various conferences, if there is an opportunity, I speak at roundtables in order to raise awareness about Krymchaks.”

Throughout these activities, the achievements of the Qrımçahlar Krymchak Cultural and Educational Society are of great support for him. Since the society was founded in Simferopol (on Krylov Street), significant events for the Krymchak community have taken place: the launch of an almanac on Krymchak history, life, and traditions; the opening of the Krymchak historical and ethnographic museum; and regular meetings and exchanges of experiences and memories between Krymchaks from Ukraine, the USA, Israel, and other countries.