The Ambassadors project shows Ukrainian cities through the eyes of their famous inhabitants. In the tenth story, Nata Zhyzhchenko of the band ONUKA shows us her native Kyiv, the great and extremely diverse capital of Ukraine. Bogdan Logvynenko, the founder of the Ukraїner project, joined Nata to meet some of the people who are shaping this modern city.

— What was your childhood like in Kyiv?

— I spent my childhood in the Voskresenka neighbourhood (in Kyiv, on the left bank of the river Dnipro — ed.). I still love that place because it’s hardly changed; going there is literally like taking a trip into my childhood. I used to enjoy picking up fallen leaves with my mum after school and making herbarium collections — it’s one of my warmest memories.

— Was the sopilka (Ukrainian folk instrument of the flute family — tr.) the first instrument you played?

— First was the piano, but that was just me attempting to press the keys. My mum is a pianist. I was always begging her to teach me to play a tune, but she kept on repeating that I was too young for that. From the very beginning, she would draw marks on the keys so that I knew which ones to press. The sopilka came later — in any case, it was easier to master a six-hole sopilka than play the piano with both hands.

The singer Nata Zhyzhchenko grew up in a family of musicians and is a granddaughter of Oleksandr Shlionchyk, a renowned maker of folk instruments. It was Nata’s grandfather who taught her to play the sopilka and encouraged her love of music. In the summer of 2013, her passion transformed into the solo project ONUKA, which combines electronic music with folk motifs. The cofounders of the project are Nata Zhyzhchenko and her husband Yevhen Filatov, producer and frontman of the band The Maneken.

— Do you remember how you met Yevhen?

— We knew of each other, and used to run into each other at concerts where we were both performing. Later, in 2008, we met and started talking. At that time I was a keen moped rider and would zoom all around Kyiv. I once decided to take Yevhen for a ride to Xlib (a now-defunct night club in the Podil district — ed.). I drove at breakneck speed. It’s a wonder we didn’t have an accident, but that was our first trip together. I guess we chose the right direction back then, and we’re still flying from that mountain at the same speed in the stratosphere.

— Is there any special place for you in Kyiv?

— I lived in Obolon for a short period of time, and in Podil for a long time. Podil stayed in my heart because that was where Zhenia (short form of the name Yevhen — tr.) and I spent the longest period of our life together. It was all about walks and nightlife. Now that we live on the left bank of the Dnipro, we still often come to Podil and enjoy walking the dog here, getting inspired by the atmosphere. Here you can see how ancient Kyiv is, and how cosy it is at the same time. This combination of what can’t be combined is the very essence of Kyiv for me.

The history of the National Expocentre of Ukraine, near Holosiivskyi Park in Kyiv, began in the summer of 1958 when it was opened to the public as the Exhibition of Achievements of the People’s Economy. After the USSR collapsed, the complex went into decline and underwent multiple name changes. In 2015, however, a new administration took over; within a year, they had prepared a 40-year development plan. Over this period, they are planning to create education centres, an art residence, children’s zones, an exhibition centre, a business campus, and parkland. The projects will attract personal investments, and the investors will later on be able to manage the properties. All revenue from the operation of VDNH will be used to improve the area and its infrastructure, and also to take care of the parkland. Ievgen Mushkin, CEO of the National Expocentre of Ukraine, believes that the projected programme of changes is going to affect the way Ukrainians’ values are formed: “It’s a very powerful place. Historically, it had a strong influence on people, but that influence was artificial. According to our strategy, Pavilion 1 is going to house the Museum of Ukrainian Science. There are hundreds of museums like that around the world, but none in Kyiv, none in Ukraine. We believe this museum must be located at VDNH!”

— Do you have any childhood memories of VDNH?

— My childhood memories of it are somehow very negative: that it’s a scary, untidy, neglected place. It was very far from my childhood home, and my parents and I came here very seldom, maybe just a few times. Actually, I discovered VDNH for myself when they started reviving it, and more and more initiatives are joining in. For example, Atlas Weekend (a music festival held in Kyiv annually since 2015 — ed.), and Kurazh Bazar (a charity flea market — ed.). No Waste Ukraine (a public organisation which is introducing the practice of recycling household waste — ed.) are also opening a recycling station here.

— What are your impressions of the complex now?

— I like this complex because it has such archaic Soviet architecture, and there aren’t many complexes with such buildings left. Even the green spaces are arranged in that peculiar Soviet style, which you can’t find anywhere else in the world. All this is concentrated in one place, not that far from the city centre. I believe the complex is worth being looked after and given a new life.

— What do you think about decommunisation?

— I reckon it will be an unhealthy trend if they start a mass renaming of streets in honour of some weird contemporary heroes that nobody will remember in five years. If we tear down monuments to Stalin and Lenin on every street corner, this is absolutely normal. We might just leave one as an artifact of pure evil, so that we don’t forget. In any case, we can’t just erase history. We have to remember it, in order to prevent it from happening again. But when things get over the top, then I’m negative about it: too much is unhealthy.

In 2014, Kurazh Bazar launched a new festival with a charitable goal. Besides second-hand clothes, they sell new designer clothes made in Ukraine or abroad. The charity flea market used to take place at Platforma Art Factory (a factory converted into an art space — ed.), but later moved to VDNH. According to the project’s founder, Aliona Hudkova, the project is proof that charity and entertainment can go hand in hand: “VDNH was lost on our generation because this place was considered full of Soviet archaism. It was outdated and lame. So, when we started coming here, we gave it a new dose of life and fun. A lot of people come here each month for the charity flea market, Kurazh Bazar: 15 thousand on average. Different artists perform here all the time”.

— Do you consider Kurazh Bazar to be a success?

— The project is very inspired, I believe. It has changed the way people see charity in Ukraine. It’s one of the projects which proves that charity can be combined with music, fashion, and fun. It’s amazing that there are people who make a difference and are driven by the desire to change the world. That’s a whole new level of human improvement, when you live for others. And I’m happy that there are people who support this trend.

The public organisation No Waste Ukraine was founded in 2015 to give Ukrainians an opportunity to recycle household waste and thus reduce the negative impact on the environment. They opened their first recycling station near Demiivska metro station in Kyiv, where they organise events dedicated to the proper handling and sorting of household waste. Yevheniia Oratovska, the organisation’s founder, is hoping to open another recycling station on the territory of VDNH, and she’s happy that more and more environmentally-conscious and responsible Ukrainians are boosting the demand for projects of this kind: “It’s like a self-service station. Our consultants help people figure out what to put where. We have rules, though: everything must be clean and compacted. It’s like a portal: you walk in thinking about rubbish, and you go out thinking about something totally different. I mean, people don’t expect waste to look nice. Typically, it’s filthy and it stinks, but at our station it’s the opposite, because people take care of their waste at home. When they bring it to the station, it really looks like a resource.”

— Do you support the initiatives of Yevheniia Oratovska, namely No Waste Ukraine?

— Yevheniia and I have a lot in common, and I admire her. They are trying to introduce recycling, but it’s hard to make it work since there’s no organised system on a national level. In Kyiv there are a few stations that accept sorted waste, and there might be some in other big cities too.

In September 2018, ONUKA released a music video for the song Strum, filmed at one of the city’s dumps, drawing attention to the pollution of the environment caused by household waste. With this video, Nata Zhyzhchenko launched an environmental initiative.

— Have you helped the organisation No Waste Ukraine in any way? |

— We’ve started an environmental initiative called Ecostrum. The YouTube monetisation from each view, share, or like of our video is transferred to the accounts of No Waste’s recycling stations. Zhenia Oratovska supported us, and we did the project together.

— Have you noticed that the attitude to recycling is changing?

— I feel that the whole generation is changing. There are lots of environmentally-conscious people. Some manage to set up compost systems on their balconies. I mean, there are people who really care so much that I’m amazed.

Ancient folk instruments can be forgotten over time. If there are no craftsmen who can manufacture or restore a certain instrument, it can disappear altogether. The buhai is a musical instrument which gained recognition after ONUKA performed during the interval at Eurovision 2017 — people were captivated by the instrument’s unusual look and sound.

— Have you noticed that you’re making a difference with your music?

— That was one of my goals. The buhai is a very rare instrument, unlike the sopilka or bandura, which are familiar to everyone. My personal aim is to show them to Ukraine and to the world, because many young people don’t even know about these instruments.

— When did you first find out about the buhai?

— As a child, when I saw it in my grandfather’s workshop. I was shocked that something like that even existed: a horse tail sticking out of a barrel.

slideshow

— Have you seen it in use since then?

— We found it in an orchestra. It’s used with other folk instruments, but only superficially. I don’t like the parts the buhai gets. I wanted to use its timbre in my music. This is how that bass appeared in our song Vidlik. Of course, it’s sampled, but it was still played live. And when we’re playing with the orchestra, it’s duplicated live.

— Your grandfather was so devoted to creating his instruments. Did you admire his work?

— Yes, my grandpa is a legend. I don’t think there’s anyone else like him — or, if there is, I haven’t met them yet. I have a dream of restoring the Chernihiv Musical Instrument Factory, but it needs huge investment. When I have an idea, I might spend a long time moving towards it, but I still somehow have an influence on its implementation, even if it’s implemented by someone other than myself. I feel that a musical instrument factory is something magical and wonderful. And remembering the scale of the Chernihiv factory, it’s so sad to see what it’s turned into now.

At the end of August 2019, ONUKA set out on a tour of China with the support of the Embassy of Ukraine in the People’s Republic of China. The band played two solo concerts and took part in the 12th International Festival of Youth Art in Guangzhou, where they presented the unique blend of Ukrainian folk instruments and electronic music to a Chinese audience.

— What was your impression of your tour in China?

— We had an unusual experience in China. We had three concerts, all in huge halls with a capacity ranging from 500 to 1800 people. And we were sold out! Our audience was mainly Chinese, with around 15% to 20% from the local Ukrainian community. I mean the concerts were organised for a native Chinese audience.

— Do you have any funny memories of the tour?

— We took part in a festival where we played only one track. It was a collective concert of performers from different countries, and we were among them. It was very weird because there were classical bands: for example, a Georgian dance group or Chinese dancers lip-syncing… And there we were with our electronic track, which stood out like a sore thumb, but both the spectators and the other artists backstage appreciated it.

— Are you an active user of social media?

— I deleted all the social media apps from my phone, but still have one on my computer. I hardly ever log in — just to check some statistics — but on the whole, I’ve freed myself from those chains. I might be thinking like an old lady, but I’m happy that there were no social networks or smartphones in my childhood.

— So you decided to give up social media?

— Yes, I did. I still have Instagram though. At first I deleted it too, but then reinstalled it as I realised I had no connection with my team. But I got rid of the other networks, especially Facebook.

— How long has it been since you gave up social media?

— I did it last December (2018 — ed.). Removed everything from my laptop, my phone. After a while, I realised how much time I’d freed up after I stopped all that mindless scrolling. I started reading even more books when touring, and watching films in the original language, which I’d always wanted to do, but had no time for because of all the scrolling.

In the summer of 2018 in Reitarska street in Kyiv, the first Block Party took place, a street festival organised by the local businesses. It’s an event involving all the businesses from the nearby streets, where visitors can have fun and relax. The organisers spend part of the money raised at the event on improving the street by installing rubbish bins and renovating the façades of the buildings. Andrii Tytarenko, the initiator and organiser of the event, dreams that visitors will come to Reitarska to have a good time not only during the festival, but also on any regular day: “The history of the Soviet Union in Ukraine broke the tradition of spending leisure time in the streets of the city. The shopping streets, where people would come to drink coffee, go shopping, go for a walk, were replaced with shopping centres. Now, people have to go to huge buildings made of iron and concrete to enjoy their free time. We realised that our street can be a sort of enclave where you can come to relax and buy products made in Ukraine”.

— What do you think about the modernisation of Kyiv?

— I really like Reitarska Street because it’s such an archaic antiquity, but it’s been modernised a lot. And the Block Party itself is the best thing happening in Kyiv in terms of urban development. It’s really awesome to be a part of it.

In December 2018, the contemporary art gallery The Naked Room opened in one of the buildings on Reitarska Street. One of its founders is the film director Marc Wilkins, who moved to Kyiv from Berlin to support Ukrainian culture. The gallery mostly exhibits the works of young Ukrainian artists, and visitors can get acquainted with the art while enjoying a cup of coffee or a glass of wine. The gallery also has a book corner where visitors can purchase books on contemporary art, architecture, photography, and design.

— Do you know Marc Wilkins, the co-founder of The Naked Room?

— We met while filming a video we worked together on (an advert for a mobile phone operator, in which Nata Zhyzhchenko played the main role — ed.). As it turned out, Marc was so inspired by Kyiv and the events of 2013-2014 (the Revolution of Dignity — ed.) that he sold his house in Berlin, moved to Ukraine, and became a fighter for the freedom of Reitarska Street. He initiated protests against new building projects in the neighbourhood and opened the Naked Room gallery.

— Why do you think Marc Wilkins chose to open a gallery here?

— He saw the state of contemporary art in Ukraine: how snobbish our galleries are, the high prices, and the lack of interaction with creative young people. He decided to create a more up-to-date gallery with a library, lounge zone, bar, and works of art that are affordable for ordinary people.

— What was the music like in your childhood?

— Terytoriya A (a Ukrainian daily music chart TV show — ed.), or any other show of that time, was basically a bunch of singers who just lip-synced to pre-recorded and edited tracks. I believe that from the early 1990s to the 2000s, there was a general degradation of culture. All those festivals organised in a rush, god knows who was performing there. There are a lot of music channels which I’m very negative about; sadly, they’re still around these days. And what they’re producing now is still an insult to the general public, even though those singers might not be lip-syncing anymore.

Фанера(сленг.)

Підвид фонограми, коли виконавець з допомогою попередньо записаної пісні імітує спів під час концерту.

— How would you describe the current state of Ukrainian music?

— I feel that we’re getting out of that pit now. I guess this movement could be felt from the beginning of the Revolution of Dignity, and the number of original and powerful singers is growing.

— Which musical projects are you a fan of?

— I see DakhaBrakha as an example to follow in all respects: they’re successful abroad, they’re amazing live, they’re original. I won’t stop repeating that they’re a ‘musical bicycle’ invented in Ukraine.

Ukrainian singer Yana Shemaieva, aka Jerry Heil, used to make videos in which she covered Ukrainian and foreign hits. When searching for a sound producer, she turned to the recording studio Vidlik Records, created by Yevhen Filatov and Nata Zhyzhchenko. The couple saw Yana’s potential. In October 2017, the label released Jerry Heil’s debut mini-album, De miy dim (‘Where is my home’ — tr.) which included four songs.

— Jerry Heil was your discovery, wasn’t she?

— She was already a blogger, covering songs a capella. That’s a common practice all over the world, but the difference is that this girl started filming and editing it all by herself. I think she’s a self-made woman. That’s a great achievement: to do everything yourself and get a result like that. The lyrics, the presentation, and the overall thinking behind it — it’s all tangible.

— What do you think of Jerry Heil’s image these days?

— I don’t like the genre she’s working in. I think she’s worth much more than that. That one song Okhrana otmyena is cool and funny, but it sets the direction for the next ones. So, with the release of Vilna kasa and Natverkai, her deeper songs have less chance of reaching their audience. She writes really awesome, deep, and unique songs. I hope she can find her true self eventually, and present that self to her audience.

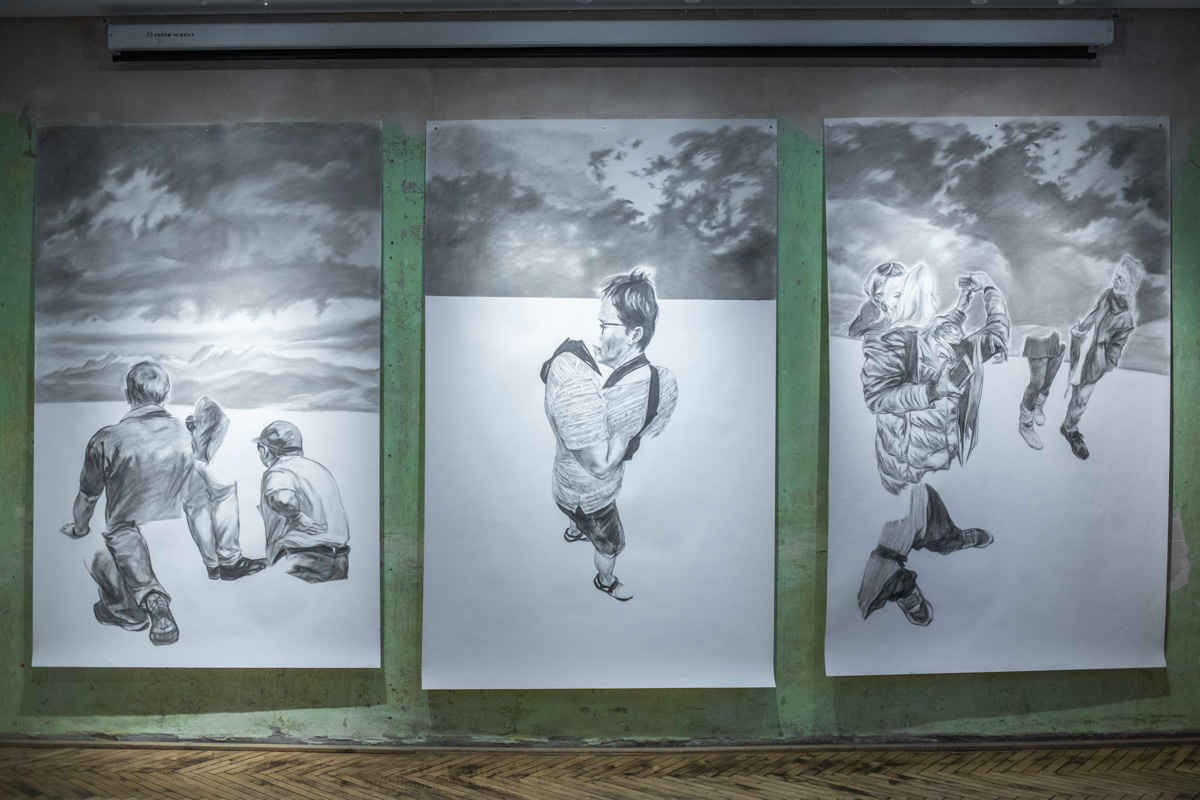

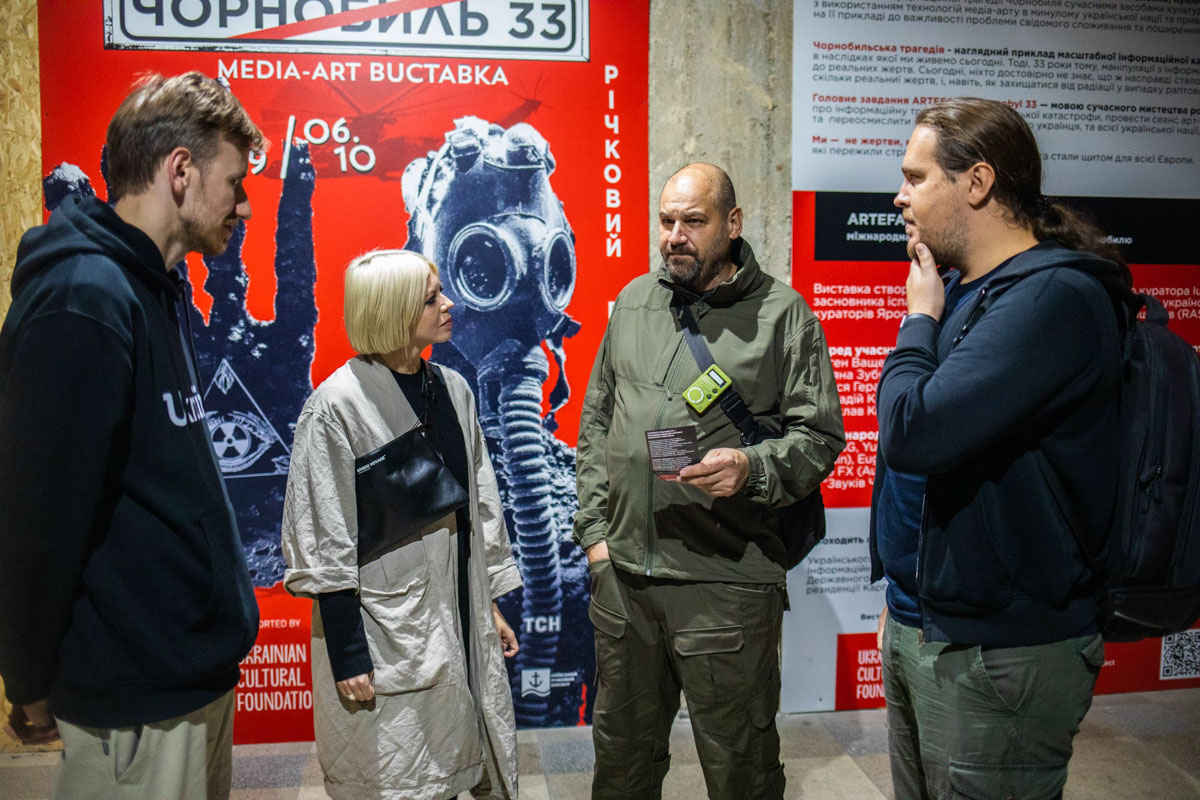

In 2012, the Ukrainian composer Volodymyr Savin went to the city of Prypyat to record the sound of musical instruments abandoned after the accident at Chornobyl Nuclear Power Plant. Over seven years he undertook 25 trips to search for the instruments and collect the recordings. Having recorded twenty musical instruments, Volodymyr organised that into a virtual ‘museum of sounds’ called Pripyat Pianos: “The city died, people don’t live there anymore, but there are so many pianos. Nobody’s using them. For a musical instrument that means death. In 2012, I played them for the first time, heard that they still worked. And I had the idea of sampling them. Now there’s an instrument made up of twenty pianos. Any composer in the world can take it and play any music they like. Thus they are giving a new life to these instruments”.

— How is your story connected with Chornobyl?

— First of all, my father was a liquidator. Ever since my childhood I’ve known what Chornobyl was. And then, I guess it was curiosity that guided me during my school years: newspaper articles, books, notes from my conversations with my father. And then my interest had a purpose. At university (Kyiv National University of Culture and Arts — ed.), I defended my thesis whose topic was “The influence of the [Chornobyl] accident on the ethnic region of Polissia”. I did research into the music of the people who came to live there, and of those who were evacuated. From the point of view of ethnography it’s a problematic subject. But everybody who’s interested in that subject knows that it never lets go.