They say that clayware — a jug, a kumanets (a ceramic vessel for water and wine that is common in Ukraine) or anything else — is like a living creature. Potters themselves referred to their wares as if they were alive, using the word “soul” for counting. They would say something of the kind, “I have made twenty souls of pots, forty souls of jars…”

Creation of ceramic wares is an ancient craft associated both with the material and artistic culture of many nations. The flourishing of the pottery art in Ukraine was encouraged by the availability of high-quality deposits of red, red-brown, and light grey clay.

Nowadays when crockery is a mass production item, there are few private homesteads that keep making pottery and even fewer of those that turn it into their lifework. However, in the old-established and indigenous Ukrainian pottery centres there are craftspeople who create traditional pottery, preserve and perpetuate this tradition.

Pottery of Opishne

Pottery has been thriving on the territory of Ukraine since the times of the Cucuteni-Trypillia culture (a Neolithic–Eneolithic archaeological culture (c. 5200 to 3500 BC) in Eastern Europe). This craft has been constantly developing since it has always been in demand. In the 16th century, there were over ten big centers of pottery. Till now the village of Opishne, in Poltavshchyna, has been one of the biggest and the most famous among them. To find out more about the history of Opishne, the Poshyvailo family and the National Museum and Reserve of Ukrainian Pottery, read our story.

Ceramics from Opishne has been to a number of international exhibitions and has been exported to most of the continents.

slideshow

Clayware preserves traditions and evolves through centuries. Great variety of dishes in Ukrainian cuisine and rich ceremonial culture of Ukrainians encouraged the appearance of various crockery of different size and shape.

Floral motifs — flowers, bunches of grapes, spikelets and branches — prevail in paintings on traditional ceramics from Opishne. Warm hues of red and brown are combined with speckles of green and blue.

Opishne is a place where they create painted crockery of any kind, be it jars, plates, kumanets, baryltse (a vessel that resembles a barrel), zoomorphic crockery (stylised animalistic images), fine figurines and toys. The latter is what makes Opishne so famous.

slideshow

Opishne zoomorphic crockery comes in shapes of bulls, goats, horses, birds and alike, though a sheep and a lion are the most popular with Opishne craftspeople. They also make whistle toys or zozulytsias that may resemble a horse, a rider, a rooster, a ship, a goat, or a deer.

Craftspeople of Opishne do not draw sketches of their creations. It is believed you will not find two alike items among a variety of clay works. The variety of shapes and functionality of those goods — either tiny toys or 25-30-litre-vessels — are a topic of another long story.

zozulytsia

Аn instrument used on the territory of Ukraine in the times of the Cucuteni-Trypillian culture.

Pottery and painting

Long preparation work foreruns the creation of clayware. At first, a craftsman retrieves the clay from its deposits that are called clay pits. After that, he piles clay in a fenced spot where it is left to mature and stirs it from time to time. Clay matures in natural weather conditions: soaks with rain, dries under the sun, freezes during frosty weather. Next, clay is hammered and chipped, then soaked in water and left to settle down. After that, it is filtered and dried out. All this process is conducted to remove all particles and solids that can change the quality of the final product. A potter can start working with well-settled, wetted and well-mixed clay.

The final product is formed either on a potter’s wheel or manually. Nowadays there is an opportunity to use plaster moulds. Just like it used to be years ago, small elements are created manually and then they are glued to the main product with liquid clay. After moulding, clay has to dry in natural conditions without drafts. After that, the product is annealed in an oven, gets covered with the glaze or painted and annealed in the oven one more time at a higher temperature.

The technology of painting the product before the first annealing is called “painting on raw pottery”. This technology is typical of the Opishne tradition of pottery painting.

Engobes, the clay slips coatings, are used for painting. At first, the product is covered with a slip that creates an even tone. After second drying, they are painted with the help of a rubber bulb with a straw on the tip. What makes this style so complex is that the final colour of engobe does not reveal itself under the glaze until it has been annealed.

Ornament painting with engobes is conducted using such ancient techniques as rizhkuvannia (creating a contour of an ornament with the help of a rubber bulb) or fliandrivka (putting paint on the pottery and dragging a special copper hook through it while the potter wheel is rotating and a pattern is being created like that). Rizhkuvannia is used for straight and wavy lines, dots, leaves and other ornament elements. Fliandrivka is characterized by accurate zigzag fibrous lines that are symmetrically placed on both sides of the product.

There was no strict divide between everyday and festive crockery in Ukraine. The quantity of crockery in a household depended on prosperity and number of family members. For instance, a family with moderate means used about 15 pots of different size and proportion. Pots with wide sides were called “pukatyi” (chubby) and narrow ones were called “ploskun” (flat ones). Less prosperous families did not have separate crockery for festivities, so they used everyday dishes for all purposes. That is why it is common to differentiate Ukrainian clayware according to its shape rather than its applicability.

In Opishne, besides pots, they produce different kinds of plates, such as a rynka (a flat pot that resembles a frying pan), a makitra (a big clay bowl with a rough surface for battering eggs and sugar or poppy seeds), jugs, frying pans, bowls, covered pans and things alike.

slideshow

Notions “pot” and “jar” are often confused. A pot is a round vessel of chubby shape which is used for cooking food, while a jar is tall and is used for storing liquids.

A sloik (a glass jar) is a tall glass vessel for confiture, jam, honey, melted pork fat, and pickled vegetables. Liquids can be kept in such vessels as tykva (a vessel with wide walls and narrow to the neck), barylo (a vessel that has two bottoms and barrel-like walls), kumanets (a circle-shaped decanter for alcohol drinks) and pleskanets (also a circle-shaped vessel but without an opening in the middle).

slideshow

For baking an Easter paska (traditional Ukrainian sweet Easter bread), they produce special baking cups that are called a tazok and a stavchyk, also known as paskivnyk.

Opishne craftsmen

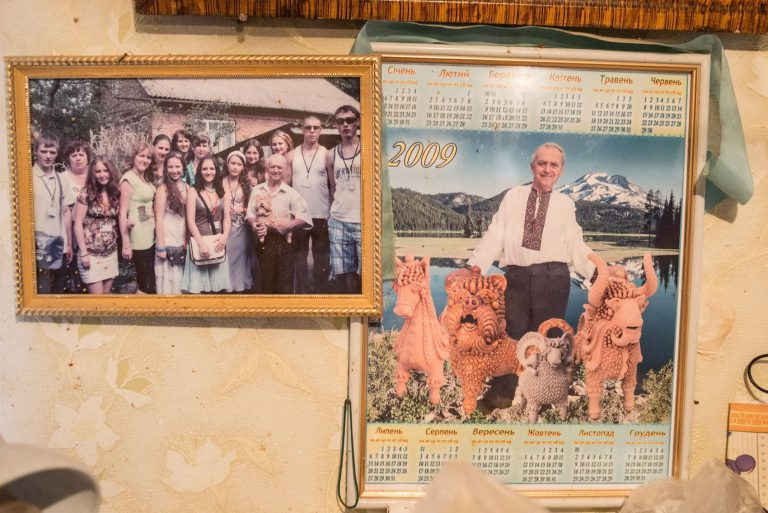

Vasyl Omelianenko

This year Vasyl Omelianenko turns 93 years old. He took clay into his hands when he was nine years old. He saw rooster-toys at his neighbor’s home.

— My brother and I begged my mother to bring us some clay. We started making whistles but nothing came out at first. First roosters were rather bad, lopsided. The clay demands diligence, otherwise nothing will come out. We kept modeling and soon learned to make pretty good rooster-whistles. Then we figured out that there were other living creatures in nature. So we started making fish, dogs, sheep. We went on with this hobby.

slideshow

Vasyl and his brother modeled their first hundred whistles and sold them to their neighbor that used to go to Poltava to sell things. That’s how boys made their first money. They considered themselves very rich. Back in 1934 when poor village family of Omelianenko was trying to get out of hunger, they survived thanks to money they got by selling clay whistles.

Before the World War II, Vasyl Omelianenko was in 7th grade. He continued his education in an evening school. In 1950 he started working at the factory “Hudozhnii Keramik” (Art Ceramics).

— They assigned me to make clay sheep at the factory. I had never done it before. A daily stint was to produce four sheep figurines, but I could hardly struggle through one. Later on, I learned how to make them and started to produce not just a daily stint but to think over some other shapes, such as a lion, a bull, a horse. I created products for exhibitions. There were supervisors at the factory, but I could make more than they were able to show. What kind of a supervisor did I need then? But if you were considered a junior worker you were dependent on him (supervisor — ed.), he showed you how to do things.

Vasyl does not make simple clayware, like jars or plates, they are not interesting to him. Though he is considered as a master craftsman of minor forms, he is also the author of large park sculptures. The most famous among them is the Lion with Two Heads. Though it is easier to anneal such sculptures piece by piece, the craftsman annealed it in one piece, having built an oven around it. He considers the lion to be a symbol of courage and strength of Ukrainians: it has two heads to see friends and enemies in the West and in the East. The sculpture the Lion with Two Heads and other creations of the craftsman are located on the territory of the National Museum and Reserve of Pottery in Opishne.

— There are many of my works in the museum. If I have some new work, they want to buy it. The pottery craft survived by virtue of the museum in Opishne. Oles (the head of the museum) managed to attract visitors from abroad. The museum boasts a variety of exhibits that cannot be seen anywhere else: one can come, take a look and learn. It has never crossed my mind to copy somebody’s work. I look and think what to add, what to remove so that it looks better.

slideshow

Vasyl Omelianenko’s works have been exhibited in Bulgaria, Germany, Great Britain, China, the USA, etc. He has many students all over Ukraine. Some of them became really great craftspeople. Vasyl Omelianenko did not give up on pottery after he had retired. He organized a workshop in his quite small house. His wife died 14 years ago. Nowadays, Vasyl considers clay craft as his second life:

— I am so used to clay that I cannot live without it. I perceive clay as a living being. Here is a piece of clay which I can use to make a new creation. It can whistle; sometimes it seems to be talking. I talk to it in my thoughts. I tell it that I have poor health though I am not old, not 100 years old yet. I still want to create something great, to make a human soul happy.

Oleksandr Shkurpela

Oleksandr Shkurpela was born in Opishne, so it comes as no surprise that he decided to engage with pottery. Having received a professional education of pottery production engineer, Oleksandr worked at the factory of “Hudozhni Keramik” (Art Ceramics). It was the rule that a junior worker had to observe the work of a senior craftsman. Trohym Demchenko was Oleksandr’s supervisor. At first, he worked at the art guild and then at the factory for 45 years.

— He (Trokhym Demchenko — ed.) has been engaged in pottery since childhood and turned out to be a very good industrial engineer. He developed the production from a zero level. Imagine the men who just returned from the World War II. They had not seen women for a while, they had not had any alcohol. They had all the freedom in the world. But they had to be held on a leash. Trohym was able to do it. He also gave them an opportunity to get high salaries.

slideshow

From the beginning of the 2000s, Oleksandr Shkurepa has been working as an entrepreneur: he creates and sells pottery. His wife helps him to decorate and sell ceramics. They are bringing up five sons. The eldest one is already dealing in pottery professionally. Younger sons Maksym, Artem, Andrii, and Mykola are studying along with making pottery and painting.

— When I look at my elder one, I get inspired and have a strong wish to do something myself. He is an extension of my hands and thoughts. Despite the young age, he knows the technology better than I used to know at his age. He has a good sense of how to heat up the oven correctly. A skill is something one has to learn and still you will not embrace everything.

Oleksandr shows us how this workshop is organized. In the basement, there is clay that has been stored since the fall. There are several kinds of it, and each of them is suitable for certain type of pottery. All the clay is extracted in Opishne. There is a huge oven in the yard, which is bigger than the workshop.

— We start the oven once a month. We prepare products and then load it. My son helps me because it’s hard to support fire in the oven for 24 hours. You cannot abandon it even for a second. The temperature has to be raised gradually, otherwise, the products will crack.

In the attic, they store the ready-made products. Oleksandr and his son are working on electric potter wheels that they made themselves.

— Pottery knowledge includes awareness of many details: how to find clay, how to prepare it for work, how to make a glaze, how to take care of the product. However, each process is interesting in its own way.

— There was a pretty formidable school of pottery in Opishne. People know about it and still remember it. If a person starts learning about pottery from ground zero, it is very hard. There are so many details to consider. I think we managed to survive and save this craft because our whole family is in it.

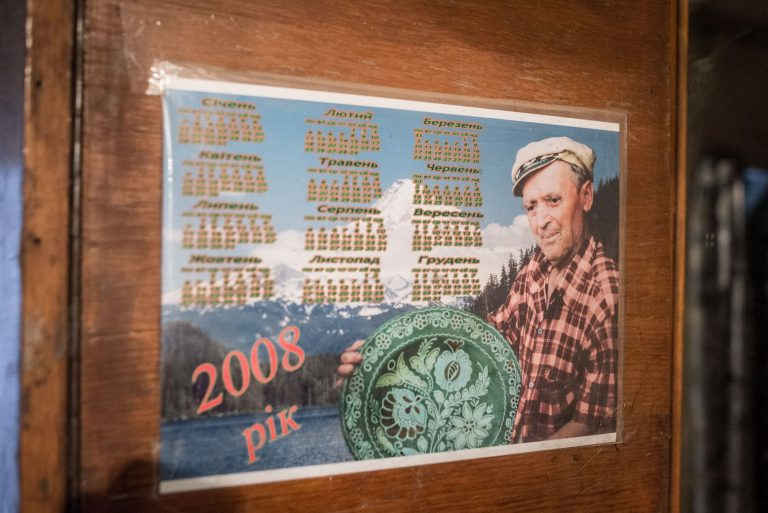

Mykola Varvynskyi

Mykola Varvanskyi is one of not many potters who are private entrepreneurs. His wife helps him by selling the products, and his elder daughter is studying with a major in pottery design. The younger daughter studies in the Arts Collegium. Mykola’s ancestors on both mother’s and father’s lines used to be potters.

— I have been making pottery for 30 years. I finished the middle school and entered the Opishne professional school at the factory of art pottery. Since that time my life has been connected to pottery. At first, I was taught at the professional school, then I was taught by the whole factory until they succeeded. Back then it was prestigious to be at the factory and to have an opportunity to take a look at how the master craftsmen work. There used to be many great craftsmen.

slideshow

Mykola tells us that there are few pottery households in Opishne that work for themselves and make their living from it. There is a dozen of those that produce pottery from time to time.

— It’s clear that there were none private productions in the USSR. There had been handcrafters before that. I don’t remember it well, but they say that taxation made people quit handicraft and go work at the factory. There was a factory of art pottery and of simple pottery. The latter one was producing mostly mass consumption goods. I worked at both factories, and since the middle of the 90s, I have been working at home. Since the 2000s, I have been a private entrepreneur.

Mykola Varvanskyi recalls how he used to go to the Hudozhniy Keramik (Art Ceramics) factory workshop and how he got inspired right away to create something more daring and complex.

— Nowadays, when I see something interesting at exhibitions or in museums, a wish to create something kicks in.

— Routine work can be different. Sometimes it’s just an order that has to be fulfilled. Creative work is not about order but about inspiration. To be inspired you need certain conditions: not to worry about what your children have to eat, to have more freedom. And a wish, wish to create plays a crucial role!