There are many villages and cities under Dnipro waters today. This is due to the construction of cascades of hydroelectric power plants (HPP) and reservoirs on the Dnipro river in the second half of the 20th century. Dozens of villages were sunk to build the last plant, Kaniv HPP. The community of villages, previously situated to the south of Pereyaslav, is looking to preserve the memory of its motherland.

Many unique landscapes, historical sites and important places of Ukrainian history were sunk alongside the building of the Kaniv reservoir. Active citizens of the sunken villages caused by HPP created an NGO “Old Dnipro”, which collects historical information and stories of witnesses, publishes books and organises cultural events, one of them being yearly “Dnipro roaring” swim.

People of sunken villages

While looking for better electricity supply and shipping in the Soviet Union, the authorities decided to build a cascade of hydroelectric power plants and reservoirs on the Dnipro river. They began building an HPP on Dnister (also read about sunken Podil village Bakota). This triggered multiple Ukrainian villages to disappear, mass migration, and significant changes to the ecosystem. Changes in the hydrological regime in the Dnipro caused a slowdown in water exchange and the pace of the river’s self-purification. Also, due to excessive evaporation of water, the river shallowed. Because of the lack of fish culverts in the Dnipro basin, valuable fish species are about to become extinct.

Kaniv reservoir, one of the six major reservoirs on the Dnipro, was the last to be constructed. It stretches for 160 kilometres and only within the Pereyaslav region, its area is about 675 m2. In the mid-70s, the Kaniv reservoir was filled with water, flooding about 20 settlements, including ten villages near Pereyaslav: Andrushi, Viunyshche, Horodyshche, Zarubyntsi, Kozyntsi, Komarivka, Monastyrok, Pidsinne, Tsybli, and Trakhtemyriv. Some villages were completely flooded, and some of them were considered unpromising. These were small settlements, which the Soviet government, seized by centralization, and they were deprived of budget allocations for culture, education and household items businesses.

Due to the planned flooding of the villages, all residents had to be forcibly evacuated and their homes and local architectural monuments demolished.

The villagers reacted differently to the relocation: some were happy to move to more modern homes with electricity and other amenities, while others saw no advantage in leaving their homeland. The evacuation of the villagers took place regardless of their wishes, so there were no residents left in the villages once the flood began.

The resettlement process lasted several years. Some families moved to neighbouring or newly formed villages. For example, instead of the village of Tsybli, New Tsybli was created, where some people from Viunyshche, Andrushiv and Tsybli were relocated. Others had to look for homes on their own. People moved to neighbouring villages or to their relatives in other regions. But over time, many families returned to their villages, where they lived almost until the flood. A resident of the flooded village of Zarubyntsi, Vira Hrynevych, recalls what happened to her family.

“Our father had four daughters, and our sister took us to the Ivanivka village (between Uman and Kropyvnytskyi — ed.). My father bought a house there, where we lived for a year. But neither my grandmother nor my mother nor we, children, settled down. It was weird; everyone was a stranger, everything was strange, and we came back. The village was already being evicted, our house was empty, and my mother came, heated the stove, and we came back. And we lived in Zarubyntsi for another year, and then they moved us to Novi Tsybli.”

Zarubyntsi stands on the right bank of the Dnipro: one part of the village is in the valley, and the other is on a hill. After the flood and evacuation announcement, the locals asked the authorities to relocate a part of the valley’s inhabitants to the hill and thus save the village but did not receive permission. Residents of Zarubyntsi gather every year to meet the rest of the village. Together, they cross the Dnipro by boat, walk through the village’s unsunken part, and enter their homes. However, they’re not their homes anymore — only a place to visit.

The authorities of that period assessed the homes of the villagers on their own and paid funds that were not enough to buy or build new houses. Borys Godun, a native of Viunyshche village, says there was little support from the state, and often it was focused only on certain benefits for individual migrants:

“The settlers were given some benefits. For the purchase of building materials, like bricks or slate. Because, at the time, whoever was building by themselves did so with difficulties. And, of course, those for whom the state helped and the people who worked on kolhosps had benefits. Why? Because it was the same kolhosp.”

Lost and preserved heritage

A few years before the flood began, the state started ongoing felling and removal of trees. Some century-old oaks were cut down, buried in ditches and later flooded. The same happened with some churches, earthen fortresses and houses of the local population: some were demolished before the flood, the rest went underwater, and only some buildings were preserved. Most churches were destroyed so that their bell towers would not interfere with ships sailing there.

Along with the sunken villages, a large part of Ukrainian history, particularly Cossack, ended underwater. In this area, some significant events of the Cossack era took place, such as the Pereyaslav Council. Taras Shevchenko loved to visit these lands: he sketched local landscapes and described the area in his poems. Residents of Viunyshche village say that this is where Shevchenko began writing his “Zapovit”. Thanks to his paintings, today we can see local landscapes and architectural monuments destroyed or flooded during the construction of the Kaniv HPP. Boris Godun says:

“Shevchenko was fascinated by the beauty of nature, which was at that time in these villages: in Viunyshche, Kozyntsi, Andrushi. Remember how he wrote about Andrushi: ‘There will be no better paradise in another world than those Andrushi’ (from a letter to a friend and doctor A. Kozachkovskyi — ed.). It’s no coincidence; he was fascinated by it all.”

The beauty of the landscapes and architecture of these Dnipro villages impressed not only Taras Shevchenko. Well-known Ukrainian directors came here to shoot scenes for their films. Here they shot the wedding for the movie “Bread and Salt” based on the novel by Mykhailo Stelmakh, “Merry Frogs” by Viktor Ivanov and the miniseries directed by Mykola Mashchenko “How the Steel Was Tempered”. In the film “Trust” by Mykola Ilyinskyi, Tsybli can be seen before the flood.

slideshow

Some of the churches depicted by Taras Shevchenko, particularly St. Georgiy’s church from Andrushi, are now located in the Museum of Folk Architecture and Life of the Middle Naddniprianshchyna. At the request of communities before the floods in 1971-1972, several examples of local architecture were transported here.

There are now several houses in the open-air museum with a povitka (a room for cattle and stock) and sazh (a place for fattening pigs, geese and turkeys), village yards and the church of St. Paraskeva Piatnytsia from Viunyshche. Today, this church houses the Museum of Space. It is the only museum of space in a church in the world.

In Andrushi, The Open Air Museum has organised meetings of residents of the sunken villages of the Pereyaslav region since 2010 on the temple holiday. Migrants from all over Ukraine came to these meetings, exchanging memories and stories. The organisers of the museum planned to make these meetings recurrent and to organise a communication centre for the people from flooded villages.

“So that future generations would come to the museum and see how these meetings took place and learn from eyewitnesses what migrants from the flood zone of the Kaniv Reservoir are. These meetings took place over four years. Well, and then it somehow subsided all by itself.”

Unfortunately, only some of the monuments from the flooded villages have been preserved. Most of them (for example, the church in Kozyntsi) were either destroyed or ended up underwater. The church of the Holy Prophet Illia in Tsyibli remains unsunken. The ruins of the church are open for visits. The surviving houses and temples, which are now housed in the Museum of Folk Life in Pereyaslav, are maintained in good condition. It’s an opportunity to see examples of local architecture of the time.

Temple holiday

A local holiday celebrating a saint or an evangelical event, which gives a name to the local church.

“Old Dnipro”

To preserve the memory of the sunken villages of the Pereyaslav region, the former inhabitants created an NGO, “Old Dnipro”, in August 2015. As all information concerning flooding and resettlement has been unavailable for a long time, Ukrainians know very little about the history of these villages. Therefore, the organisation’s members try to gather as many facts and materials as possible to reproduce and preserve the history of the villages that went underwater, their population, customs and the way of life. They work mainly with open archives, people’s memories, photos and films.

Members of the NGO “Old Dnipro” collect materials and publish books with memories of flood witnesses and their stories and photos. Since 2017, the “Old Dnipro” group has presented a book about one of the villages annually.

slideshow

The organization’s team includes journalist Mykola Konovych, the participant of the Kaniv HPP construction Vitalii Ivashchenko, the expert of the GIS Association of Ukraine Oleksandr Melnyk, organizer and regular participant of the annual swim in memory of underwater villages “Dnipro Roaring” Anatolii Bryk and Deputy Chairman of the NGO “Old Dnipro” Oleksandr Sulima. Mykola Konovych says that he was invited to the team as the author of books about sunken villages:

“It all started with Andrushi. The second book was about the flooded Pidsinne. Here, I acted as an author-compiler: I took those materials, compiled them, and edited them. And since the relations with Trakhtemyriv remained very close, I am acting here as an author because it went through my soul, my heart, and I consider it my second homeland. And that is how this book was born.”

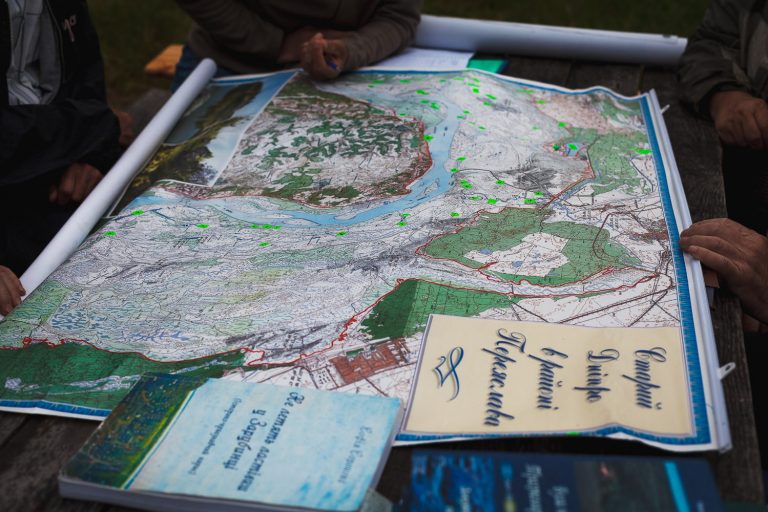

Besides historical publications, the NGO “Old Dnipro” members jointly developed a map of the area which went underwater and marked flooded architectural and natural monuments and the sites of important historical events. This map will be used for tours through flooded villages on the Dnipro later.

The organization’s members plan to move the map of sunken villages into virtual reality and organize virtual trips so that everyone can see what these lands looked like before the flood. They have already conducted an aerial photoshoot from a drone to implement this idea. They plan to “revive” usual tours on the Dnipro with augmented reality. Vitalii Ivashchenko, the head of the NGO, tells us how the future tours through flooded villages will look like:

“I want to be able to virtually fly to this flooded area and see these sunken villages, virtually go down, go to the church in Viunyshche or the church in Andrushi, go to school and see how people lived.”

Dnipro Roaring

One of the most significant projects of the NGO “Old Dnipro” is the annual “Dnipro Roaring” swim. It is a sport and cultural event designed to draw attention to the sunken villages of the Pereyaslav region, tell their history, and form ecological consciousness.

The Activists of “Old Dnipro” have organized a swim and developed a route annually since 2016, together with the public initiative “Root of the Nation”. The event combines two programs: the actual swim and the “land” part, and a more cultural program, where the team presents new books about flooded villages, shows photos of the inhabitants, holds workshops and plays movies.

An obligatory element of the cultural program is the performance of one of the former inhabitants of the flooded villages. In previous years, the guests were natives of Viunyshche Ivan Shpytal, historian and author of the three-volume “Ukraine in front of God and the world” and author of the book “Sunken villages of Pereyaslav region” Mykola Chyrkov.

slideshow

Every year, the swimmers cover a distance of 3 kilometres crossing the Dnipro and swim over the place where once were villages. Everyone who wants to discover the region and get acquainted with its history joins the swim. Professional swimmers are invited to try the distance of 10 kilometres.

The main organizer and swim idea creator, Mykola Bohatyr, tells about the purpose and plan of the event.

“The “Dnipro Roaring” swim is not just a swim; it is something more. It is a patriotic upbringing; it is an act of history preservation; and it promotes a healthy lifestyle. It attracts attention and unites amateurs and activists of any age around it.”

“Root of the Nation” and bicycle expeditions. Mykola Bohatyr

The “Dnipro Roaring” swim began with bike rides organized by Mykola Bohatyr in 2012-2013. At first, he travelled on his own, took a camera with him and took photos of historical and cultural monuments around Pereyaslav. However, there was a need to expand the team, and in 2014 Mykola and like-minded people founded the public initiative “Root of the Nation”.

Later, cycling trips turned into bicycle expeditions. They combined several of Mykola’s passions: cycling, history and preservation of cultural monuments. Mykola and his team rediscovered exciting places in the Pereyaslav region and developed a considerable archival base to create tourist routes, as well as cultural and environmental events.

“Because you go, you look for something, you discover something new. You see a century-old tree that could be one of the tourist attractions in the future. It has a fascinating history; it needs to be preserved. You start exploring around this tree — you see something more. And you see the uniqueness that, if you do not influence these processes, they can disappear or be forgotten.”

Among the objects that Mykola and his team are rediscovering for Ukrainians are springs, century-old trees and architectural monuments of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The initiative participants pay a lot of attention to is the century-old trees, which, unfortunately, have survived only in the form of museum specimens. Many of them have entirely disappeared. Mykola plans to create an exposition, “Trees of Outstanding Ukrainians”, from the samples of these trees.

“In Ukraine, there are a large number of trees that are related to some prominent Ukrainian figures. Here, for example, is Lesya’s ash tree, which grew until recently in Lutsk, near the famous Lubart Castle. Lesya Ukrainka stayed just nearby. This tree is related to the poetess, but it was overgrown. But we managed to get a cut of this tree through partners, through the Lutsk city council, as well as a slice of Zalizniak oak, a fragment of Zaporizhzhya oak.”

Later, Mykola joined a local amateur triathlon team and set a personal goal: cross the Dnipro. This goal then turned into the idea of the swim “Dnipro Roaring”. The swim organizers are happy that every year the event gathers plenty of people willing to cross the Dnipro and learn the history of sunken villages and consists of regular participants.

The organizers plan to collect all the events into the book “Stories of the Dnipro Roaring”. They also hope to present “Fragments of trees of prominent Ukrainians” at the Museum of Folk Architecture in Pereyaslav. Mykola Bohatyr says that there is still a lot of inspiration, ideas, projects and plans because he wants to talk about this region as much as possible. And as long as the memory of the former inhabitants of the flooded villages is alive, it should be integrated into Ukrainian history.

“The preservation of the memory of sunken villages is a matter of honour for every Ukrainian when it comes to the territories that took part in the process of state formation from ancient times to the present. The Cossack subject here is quite widely known, for example, the previously mentioned Trakhtemyriv as a location of the Cossacks. Shevchenko is also central to the terittory.”

supported by

This material was created with the support of the Swiss embassy in Ukraine. Ukrainer is solely responsible for the content. The opinion of the material creators does not necessarily reflect the views of the donor.