Zaporizhzhia, one of Ukraine’s regional capitals, is located relatively close to the front line. It is a vital hub for supporting Ukrainian defence and for receiving internally displaced people from temporarily occupied territories. The city is also an influential cultural and informational stronghold. Despite the challenges of war, Zaporizhzhian residents run exhibitions to support Ukrainians; they tell about the history and architecture of their city; they combat russian propaganda on YouTube.

Zaporizhzhia has inherited its strong personality from the Cossacks. The first Cossack fortifications were built on the Island of Mala Khortytsia. Khortytsia Island located in the heart of the city has become a national reserve housing the Museum of the History of Ukrainian Cossacks. A part of the region and a number of settlements south of the City of Zaporizhzhia are temporarily under Russian occupation including the town of Enerhodar where the Zaporizhzhia Nuclear Power Plant is located. The Russian invaders use it as a military base, and they threaten to cause a second Chornobyl disaster. However, the fighting spirit of Zaporizhzhia lives on in its volunteer initiatives. Despite the dangers and constant shelling by the Russian occupiers, Zaporizhzhian residents support the Ukrainian Armed Forces and provide assistance to people evacuating from the occupied territories.

Introducing Zaporizhzhia. Roman

Roman Akbash is a tour guide from Zaporizhzhia, a soldier and a former creative director of the local Museum of the History of Weapons. Roman used to work as a journalist, but he has always been into local history. Over time, his passion inspired him to change his job. Since 2011, he has been working as a guide, giving lectures, cooperating with museums, and continuing to write on historical topics.

Before 24 February 2022, the majority of his guided tours were in Russian. After Russia’s full-scale invasion, Roman switched to using Ukrainian with his family, friends, and in social networks. He also enrolled in the Azov volunteer unit of the territorial community of Zaporizhzhia. His first-hand experience of war made him rethink the tours he conducted. He believes that language defines meanings and creates reality:

– Many tours will change. I can already see that there will be things that I will talk about differently. Unfortunately, we are now living through what we have been told about war, what we read in books or watched in movies. I can only hope that this will all end as soon as possible.

Roman says that the city has “put on” military fatigues since February: its residents put up anti-tank hedgehogs and concrete barriers on the roads, and they sealed the windows with adhesive tape to protect themselves from shards of glass. In his opinion, now more and more people have started to switch to Ukrainian and unite. Zaporizhzhia NGOs are really strong: volunteers have learned to solve most issues related to the defence of the city quickly and efficiently:

— The volunteer movement in Zaporizhzhia never ceases to pleasantly surprise me. We have volunteer workshops and even entire “factories” that produce things needed for defence.

Not only civilians but also volunteers who join the territorial defense forces act in a coordinated manner. The government provides weapons, ammunition, and Starlink satellite receivers for the units. However, the rest of the things have to be bought at the volunteers’ own expense.

– Zaporizhzhia is my greatest love… My whole life is there and I will be a more effective soldier in Zaporizhia because I know it very well and many people here know me.

Roman’s reputation helps to quickly solve any difficult issue: people immediately respond to his requests. Roman also uses his cultural blog to earn money for the things he needs for the military service. As before, he publishes interesting facts from the history of Zaporizhzhia. He encourages his followers to send money to the military in exchange for this information. Thus, he raises funds for his unit and for friends who also serve in the territorial defence:

— I believe that the most valuable thing that I have, apart from my nearest and dearest, is what I know and my tours. I am now exchanging the information I have been collecting for the support of good people.

In his spare time, Roman researches the history of place names in Zaporizhzhia. On his Facebook page, the guide convinces people to vote for street name changes and calls for de-Russification. He says that there are as many Russian names among urbanonyms (names in the public spaces of a city) in the region as there are Ukrainian ones.

— You can find 12 names related to Moscow on the map of Zaporizhzhia. Twelve places are named after one place, Moscow, and we do not have, for example, a street named after Lviv.

As of summer 2022, it was proposed to rename more than 300 city streets and squares that have been associated with Russia. Working groups have been created to develop a register of new names and to propose them to the city council for approval.

Roman has a personal motivation for change. His daughter goes to school, where she studies the history of Ukraine. He does not want her to wonder why she is surrounded by places associated with the aggressor state.

— Imagine, she learns at school that Dzerzhynskyi is a negative figure in the history of Ukraine. And then she walks to this very school down Dzerzhinskyi Street. This will make her ask me one day: “Dad, why am I still walking down Dzerzhinsky Street if you and the teacher tell me all these horrible things about him?”

Not only places and streets have Russian names, but also cultural institutions. The city has a philharmonic named after the Russian composer Mykhailo Glinka. Next to the concert hall is his monument which was covered with sandbags to protect it from Russian missiles. Roman finds it deeply ironic:

— As it turns out, the residents of the Ukrainian City of Zaporizhzhia who are suffering from Russian missile attacks themselves need to protect the monument to a Russian composer in case Russians may strike it and destroy it.

Roman misses his favourite job. Before the coronavirus pandemic began in 2020 and restrictions on public gatherings began, his tours gathered up to fifty people.

— I really like to change people’s opinion from the idea that Zaporizhzhia is something uninteresting, that there is nothing there except for Khortytsia, Dnipro Hydroelectric Station (DniproHES) and factories.

Because of covid, the number of people willing to learn about the history of Zaporizhzhia has decreased in recent years, and during the full-scale war, tours stopped altogether, but Roman is full of hope:

– People don’t really know history. That is, I actually still have a lot to do. This is what I miss most, I want to gather a bunch of people, and take them on a city tour, but we know that now there are other, more pressing matters. But I’m already preparing many new routes!

Pictures of Ukrainian Resistance. Natalia

Natalia Lobach is an urban planner and designer from Zaporizhzhia who since the beginning of the full-scale war with Russia, has begun to create posters about the indomitable cities of Ukraine. Natalia also organizes events for LGBT+ and feminist communities and guides tours of Sotsmisto — a residential area of Zaporizhzhia which was built in the 1930s and became a platform for experiments by constructivist architects of the time.

LGBT+

Is an inclusive acronym for people with different gender and sexual identities

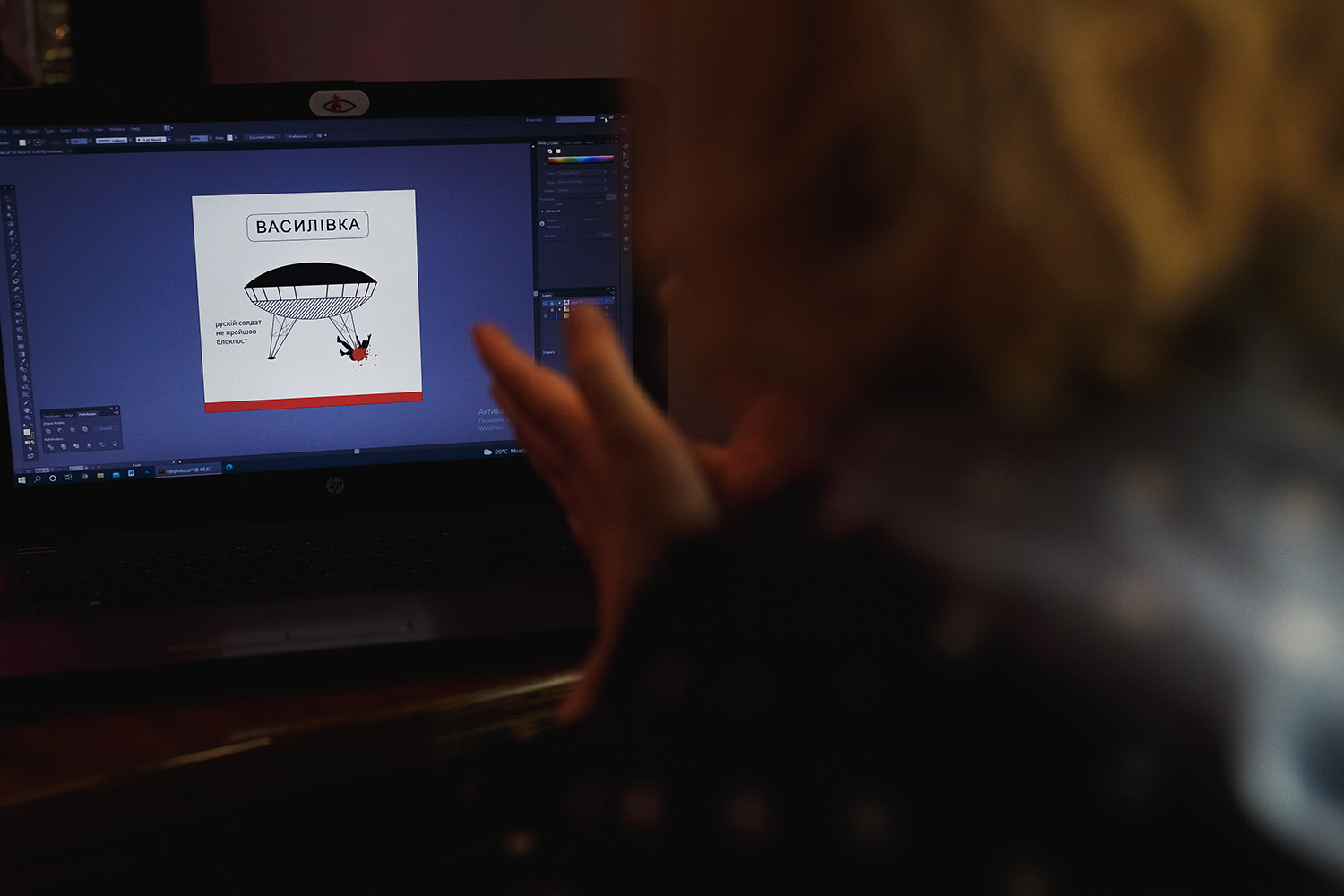

The designer creates posters about her region in two colours: red and black. Black is the theme, and red is for accents to represent the blood of the enemy. The central figure on most of the posters is a Russian soldier, who the author swipes at and uses various metaphors to imply that invaders can find only death on Ukrainian land.

— Red is for love, and black is for UPA (UPA is an acronym for Ukrainian Insurgent Army). I want to show that he (a Russian soldier. — ed.) disappears. At first, I drew how their tanks, planes, and weapons were crumbling. But then I realized that it is not a piece of iron that is attacking us. We are being attacked by people, and the fewer of them that are here, the safer we will be. That is why they are of the colour of blood in my pictures.

In May, there was an exhibition with Natalia’s posters displayed in the windows of the local Tourist Information Center. The illustrator believes that the concept of the exhibition was symbolic, because during the war many windows are boarded to protect them against damage, and posters reinforce this protection. The exhibition featured 8 illustrations dedicated to Enerhodar, the Sea of Azov, Melitopol, Kamiana Mohyla, Vasylivka, Huliaipole, Kyrylivka, Rozhivka, and the courage of their residents who resist the Russian occupation.

Natalia’s friend Viktoria, a psychologist, visited the exhibition and shared her impressions of the works. She could not choose a favourite poster because each of the places they show triggers memories. She feels a lack of cultural events because of the war but these posters give hope for victory and boost morale:

– I don’t know how I will perceive them many years from now, but right now they resonate powerfully with me, and at the same time, they are more than just photographs. Illustrations or posters are a quick way to “digest culture”.

Natalia makes topical illustrations almost every day. She chose the format for a reason as posters allow you to quickly convey an idea. It can take as little as 15 minutes to create a poster. She takes stories from the news, for she believes that this is a good source for creativity. Temporarily occupied Tokmak, Enerhodar, Rozivka still exist, and they stand up for themselves. Natalia’s illustrations are a tribute to those people who continue to resist. This is her response to their courage: you are visible; you are with us; we see you.

The work begins in the morning: Natalya wakes up, reads the news about the Podniprovia region, reviews the daily statistics of killed Russian soldiers and analyzes the map of the hostilities. If she sees news about towns she knows, she starts drawing. She looks into the features of the settlement and chooses symbols for illustration. For example, in the drawing about Rozivka, whose name reminds of a flower, the central element is a rose. The poster about Vasylivka is based on a recognizable local architectural object: a building that looks like a flying saucer.

Her first poster about the war was inspired by the news from Konotop, a town in the north of Ukraine whose residents resisted the invasion in early March. In one of the popular videos from there, a female local resident is standing in front of the barrel of a tank and is threatening a Russian soldier:

— I saw a video from Konotop. The woman in front of the tanks is saying: “Do you know where you are? Half of the women are witches here, you won’t get hard tomorrow.” How? There is a tank in front of her, and she is saying this.

Natalia was so impressed by what she saw that she wanted to tell about it through visual means as well. Just making a repost of the video was not enough for her:

— And I thought to myself: how to make this story stand out even more? Make another repost and write in even bigger letters: Watch everyone, it’s viral? That’s why I wanted to show in a picture what I saw in the video.

This is how a picture of a tank with a bent down gun appeared. Natalia says that subscribers immediately started reposting the illustration, and a famous Ukrainian video blogger Oleksii Durnev used the image in one of his releases on YouTube:

— As I can see, witches also spread it in the community (illustration. — ed.). There are real responses like: “Yes, we are working.” And I think, “Wow.” This is a different level.

The war changed Natalia’s approach to creativity, because it added bloody motifs to her illustrations and made her hobby a regular activity. The designer is confident that culture can fight against Russian propaganda at various levels. And illustration is one of them:

— We resist and we retake what belongs to us. Blood marks what we take back. We are on our land, and we reclaim it for ourselves.

Natalia’s grandmother survived the Holodomor, forced labour in Germany and life in the Soviet Union, so the designer is well aware of the challenges the previous generations of Ukrainians faced. However, she tries to move away from the narrative of “sacrifice and suffering” in her work and instead focuses on the strength of the Ukrainian spirit. Therefore, her posters are about the resistance movement in small towns:

— Most people living in Zaporizhzhia have their roots somewhere in the villages or towns of the region. It is important to me to deliver an empathetic message that they are seen, heard, and remembered, and that we know that it is difficult for them.

Safety in the front-line city is now relative, so Natalia cannot ignore this fact. She follows the developments and makes a deliberate decision each time whether to stay or not.

The illustrator is inspired by the Zaporizhzhia volunteer movement. She is sure that one can help in different ways and that every contribution is important. Bus drivers without hesitation agree to drive closer to the front line to deliver necessary items to the military. Her friends weave camouflage nets, cook, and collect funds for the necessary equipment for the Armed Forces. Cashiers against all odds keep doing their jobs every day. Natalia also volunteers: she even poured out a 40-year-old cognac to use its bottle to make a Molotov cocktail:

— You feel how many people there are in the city and how many cool things they do. And so many of these people. These heroes seem to be doing little things, but they are there. They are everywhere.

Information front. Tyler Anderson

Tyler Anderson is a blogger from Zaporizhzhia who has three Ukrainian-language YouTube channels. The main one is called Geek Journal. He used to tell interesting facts about films but now he debunks the myths of Russian propaganda and publishes news reviews.

The blogger’s real name is Oleksii. He and his girlfriend Yuliana started the Geek Journal channel back in 2016. As of September 2022, the channel has more than 306,000 subscribers, and the videos have more than 22 million views in total.

He was born in the now-occupied village of Nyzhni Sirohozy located between Melitopol and Nova Kakhovka. Many of his relatives remained there because the options for evacuation were risky. Tyler is trying to convince his family but they do not agree to leave yet:

– I can’t take them out because you see, grandma has goats, she can’t leave them.

Tyler has been living in Zaporizhzhia for the past 12 years, but he rarely leaves the house. He says he likes to spend time with his books, comics and game console. Because of this, he calls himself “somewhat local, but not really.”

He anticipated a full-scale Russian attack, especially after the news of the build-up of Russian troops at the eastern border of Ukraine.

Tyler is not planning to leave the front-line city. However, for several years now, he has been keeping alarm backpacks ready – just in case:

– It’s just like having a first aid kit, it’s not like you’re getting ready to cut yourself. It’s just forward thinking “what if I cut myself, I’ll need to put a bandaid on that finger.” I prepared backpacks which I regularly checked and restocked, and I ate the pre-packaged meat if it was approaching its best-before date. Overall, it seems that it is simply impossible to be fully ready for a war.

After the full-scale invasion, the blogger was going to enlist in the local territorial defence unit. However, a friend convinced him that he would be more useful on the information front. Then Tyler decided to change the format of his channel. He stopped doing movie reviews and focused on creating socially important videos:

— What kind of content is trending now? Why review movies people don’t want to watch? We decided to stop making such reviews. What can be done instead? We can laugh at the Russians.

Then the “news from the gutter” column appeared on Geek Journal, where Tyler makes comic reviews of Russian news. The blogger does not really like filming about Russians, but he is convinced that Ukraine needs such content now. He is convinced that this is the war of all Russians, not just Putin or politicians:

– We need to explain quite obvious things to some people because there are still people who believe Russian propaganda. These myths must be debunked.

Tyler also made video streams with comedians of the “Underground Standup” project, where he urged viewers to send money to the Ukrainian Armed Forces. He sends the money he raises to charitable funds “Come Back Alive”, “Serhiy Prytula’s Charitable Foundation”, and local military units. He raises money for various needs ranging from ordinary phones to ballistic headphones and drones.

— Ukraine has turned into a giant charity fair with everyone contributing their bit, and it’s fantastic.

Tyler also participated in the “See You” auction organized by Kolomyia volunteers together with the Drive for Live Fest, where the highest bidder had the opportunity to meet the blogger.

He also thanks his subscribers for the funds they send in an original way: he sends photos of pets on Twitter. Tyler says that he has always taken a lot of photos of his pets, but his friends were sceptical:

— “Why do you have so many photos of those cats?” — Haha, to get a lot of money. “And you have been punning your whole life?” — And here, I actually built my career on this.

He has nine cats and a dog, that’s why there are a lot of photos. He managed to raise quite a lot thanks to his creativity:

— I decided as a joke to write “come on, people of Twitter, I’ll give you a photo of a cat or a dog of your choice in return for, say, a hundred hryvnias.” And if my memory serves me right, I sold cat NFTs for almost 60 thousand.

“Sho Ty, Diadia?” (And You, Uncle?) and “Palyanytsia Center” which attract about 600 volunteers every day stand out for Tyler among the volunteer initiatives formed during the full-scale war in Zaporizhziia. Zaporizhzhia really came together and became united.

— Their activities have reached an unprecedented scale. I’ve been to them both. The pace is simply fantastic there. Everyone is busy. Someone is making bread. Someone else is welding metal.

Tyler says that the Revolution of Dignity started a wave of Ukrainization and the first Ukrainian-language channels began to appear in social media. After the Russian offensive in February 2022, Tyler noticed a new trend: finally viewers began to be interested in Ukrainian-language bloggers whose content had been there on YouTube:

— There are a lot of channels that received a maximum of a thousand views on good days. Now they get 20 thousand views per week.

In his opinion, this will lead to an increase in quality because the number of views will give the bloggers an opportunity to invest in professional video equipment. Another ingredient of success is to do what you like:

– You just need to make content. When you make it in Ukrainian, if you put your soul into it and make people like it – that’s enough. You are already a warrior of light, a warrior of goodness. This is already cool.

Tyler is also convinced that now is the best time to make Ukrainian content:

— Today, it is a matter of national security, and it protects Ukrainian culture. As a result, it will protect Ukrainian territories as well.